The Mining Sector and Indigenous Tourism Development in Weipa, Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Transport and Roads Investment Program for 2021–22 to 2024-25: Far North

Far North 272,216 km2 Area covered by location1 5.68% Population of Queensland1 2,939 km Other state-controlled road network 217 km National Land Transport Network2 211 km National rail network See references section (notes for map pages) for further details on footnotes. Cairns Office 15 Lake Street | Cairns | Qld 4870 PO Box 6185 | Cairns | Qld 4870 (07) 4045 7144 | [email protected] • continue construction of road safety improvements on • commence installation of new Intelligent Transport Program Highlights Gillies Range Road Systems on the Kuranda Range section of Kennedy Highway, jointly funded by the Australian Government • commence construction of the Bruce Highway – Cairns and Queensland Government as part of the COVID-19 In 2020–21 we completed: Southern Access Cycleway, jointly funded by the economic recovery response Australian Government and Queensland Government • completed paving and sealing paving of a section of • commence early works on the Cairns Ring Road (CBD Peninsula Development Road at Fairview (Part B) • continue design of a flood immunity upgrade on the to Smithfield) project, jointly funded by the Australian Bruce Highway at Dallachy Road, jointly funded by the Government and Queensland Government • an upgrade of the Clump Point boating infrastructure at Australian Government and Queensland Government Mission Beach • commence upgrade of the culvert at Parker Creek • continue construction of a new overtaking lane on Crossing on Captain Cook Highway, Mossman, as part • construction of the Harley Street -

Weipa Community Plan 2012-2022 a Community Plan by the Weipa Community for the Weipa Community 2 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 Community Plan for Weipa

Weipa Community Plan 2012-2022 A Community Plan by the Weipa Community for the Weipa Community 2 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 Our Community Plan ..................................... 4 The history of Weipa ...................................... 6 Weipa today .................................................... 7 Challenges of today, opportunities for tomorrow .................................................... 9 Some of our key challenges are inter-related ............................................ 10 Contents Our children are our future ..........................11 Long term aspirations .................................. 13 “This is the first Our economic future .....................................14 Community Plan for Weipa. Our community ............................................. 18 Our environment ......................................... 23 It is our plan for the future Our governance ............................................. 26 Implementation of our of our town.” Community Plan .......................................... 30 WEIPA COMMUNITY PLAN 2012-2022 3 Our Community Plan This is the first Community Plan for Weipa. It is our plan How was it developed? This Community Plan was An important part of the community engagement process for the future of our town. Our Community Plan helps us developed through a number of stages. was the opportunity for government agencies to provide address the following questions: input into the process. As Weipa also has an important role Firstly, detailed research was undertaken of Weipa’s in the Cape, feedback was also sought from the adjoining • What are the priorities for Weipa in the next 10 years? demographics, economy, environment and governance Councils of Napranum, Mapoon, Aurukun and Cook Shires. structures. Every previous report or study on the Weipa • How do we identify and address the challenges region was analysed to identify key issues and trends. This Community Plan has been adopted by the Weipa Town that we face? Authority on behalf of the Weipa Community. -

Mobile Coverage Report Organisation of Councils

Far North Queensland Regional Mobile Coverage Report Organisation of Councils Far North Queensland Regional Organisation of Councils Mobile Coverage Report 4 August 2019 Strategy, Planning & Development Implementation Programs Research, Analysis & Measurement Independent Broadband Testing Digital Mapping Far North Queensland Regional Mobile Coverage Report Organisation of Councils Document History Version Description Author Date V1.0 Mobile Coverage Report Michael Whereat 29 July 2019 V2.0 Mobile Coverage Report – Michael Whereat 4 August 2019 updated to include text results and recommendations V.2.1 Amendments to remove Palm Michael Whereat 15 August 2019 Island reference Distribution List Person Title Darlene Irvine Executive Officer, FNQROC Disclaimer: Information in this document is based on available data at the time of writing this document. Digital Economy Group Consulting Pty Ltd or its officers accept no responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting in reliance upon any material contained in this document. Copyright © Digital Economy Group 2011-19. This document is copyright and must be used except as permitted below or under the Copyright Act 1968. You may reproduce and publish this document in whole or in part for you and your organisation’s own personal and internal compliance, educational or non-commercial purposes. You must not reproduce or publish this document for commercial gain without the prior written consent of the Digital Economy Group Consulting Pty. Ltd. Far North Queensland Regional Mobile Coverage Report Organisation of Councils Executive Summary For Far North QLD Regional Organisation of Councils (FNQROC) the challenge of growing the economy through traditional infrastructure is now being exacerbated by the need to also facilitate the delivery of digital infrastructure to meet the expectations of industry, residents, community and visitors or risk being left on the wrong side of the digital divide. -

College of Medicine and Dentistry Student Accommodation Handbook

COLLEGE OF MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY STUDENT ACCOMMODATION HANDBOOK This handbook provides information on your rights and responsibilities as a resident of the College’s Student Accommodation. Please read the handbook carefully before signing the Residential Code of Conduct, Conditions of Use and House Rules. Respect & Responsibility 1 ABOUT THE ACCOMMODATION The James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry manages student accommodation at Alice Springs, Atherton, Ayr, Babinda, Bowen, Charters Towers, Collinsville, Cooktown, Darwin, Dysart, Ingham, Innisfail, Mackay, Marreba, Moranbah, Mossman, Proserpine, Sarina, Thursday Island, Tully & Weipa. Regulations and guidelines The regulations of the College of Medicine and Dentistry Student Accommodation are designed to allow the maximum personal freedom within the context of community living. By accepting residency, you agree to comply with these conditions and other relevant University statutes, policies and standards for the period of occupancy. It is expected that Accommodation residents will be responsible in their conduct and will respect all amenities and equipment. Disciplinary processes are in place although it is hoped that these will rarely need to be used. Accommodation Managers The Accommodation Manager is responsible for all matters pertaining to the efficient and effective operation of the College Accommodation within the framework of JCU and College Polices and Regulations. The College Accommodation staff have a responsibility for the wellbeing and safety of all residents -

The Land Tribunals

Torres Strait Thursday Island Cape York Weipa Coen GREAT GULF OF CARPENTARIA Cooktown Mornington Island REPORTS ON Cairns Burketown Normanton THE OPERATIONS OF CORAL SEA Croydon Georgetown BARRIER Ingham Townsville THE LAND TRIBUNALS SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN Charters Towers Bowen Proserpine REEF Mount Isa Julia Creek Cloncurry Richmond Hughenden Mackay ESTABLISHED UNDER Winton St Lawrence NORTHERN TERRITORY Boulia THE ABORIGINAL LAND ACTCapella 1991 AND Longreach Barcaldine Emerald Rockhampton Jericho Blackwater THE TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER LAND ACT 1991 Blackall Springsure FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2010 Bundaberg Eidsvold Maryborough Windorah Taroom Birdsville Gayndah Gympie Charleville Roma Miles Quilpie Mitchell Sunshine Coast Surat Dalby Ipswich BRISBANE Gold Cunnamulla SOUTH AUSTRALIA Thargomindah Coast St George Warwick Goondiwindi Stanthorpe NEW SOUTH WALES REPORT ON THE OPERATIONS OF THE LAND TRIBUNAL ESTABLISHED UNDER THE ABORIGINAL LAND ACT 1991 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2010 Table of Contents Report of the Land Tribunal established under the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 Paragraph I INTRODUCTION 1 - 2 II THE LAND TRIBUNAL 3 (a) Membership 4 - 9 (b) Functions 10 - 12 (c) Land claim procedures 13 - 14 III LAND CLAIMS (a) Claimable land and land claims 15 - 17 (b) Tribunal Proceedings 18 - 20 (c) Land claim reports 21 (d) Sale of land claim reports 22 - 23 (e) Status of claims determined by the Land Tribunal 24 - 25 (f) Status of all land claims 26 IV LEGISLATION 27 - 28 V ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS (a) Staff 29 (b) Relationship with the Land Court and 30 other Tribunals (c) Administrative arrangements 31 - 32 (d) Budget 33 - 35 (e) Accommodation 36 VI CONCLUDING REMARKS 37 Claimant and locality identification Annexure A Advertising venues, parties and hearing dates Annexure B REPORT ON THE OPERATIONS OF THE LAND TRIBUNAL ESTABLISHED UNDER THE ABORIGINAL LAND ACT 1991 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2010 I INTRODUCTION 1. -

The Evacuation of Aboriginal People from Cape Bedford Mission, 19421

‘What a howl there would be if some of our folk were so treated by an enemy’: The evacuation of Aboriginal people from Cape Bedford Mission, 19421 Jonathan Richards One fine and warm winter morning in May 1942, the Poonbar, a medium-sized coastal vessel, steamed into the Endeavour River at Cooktown, North Queensland, and berthed at the town’s wharf. After she tied up, over 200 Aboriginal people carrying a small amount of personal possessions emerged from a cargo shed on the wharf. The people were herded by about a dozen uniformed Queensland police as they boarded the boat. The loading, completed in just over an hour, was supervised by three military officers, two senior police and a civilian public servant. As the ship cast off, the public servant, who boarded the boat with the Aboriginal people, threw a coin to a constable on the wharf and shouted ‘Wire Cairns for a meal!’ Unfortunately, the wire did not arrive at Cairns in time, and as a result the party of Aboriginal people was given little food until they reached their destination, 1200 kilometres and two day’s travel away. The war between Japan and the Allies was nearing Australia, and this forced evacuation of Aboriginal people was deemed necessary for ‘national security’ reasons. Although the evacuation has been written about by a number of scholars and Indigenous writers, the reasons for the order have not, I believe, been clearly established. Similarly, the identity of the forces – military or otherwise – that carried out the evacuation have never been conclusively determined. -

Far North District

© The State of Queensland, 2019 © Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd, 2019 © QR Limited, 2015 Based on [Dataset – Street Pro Nav] provided with the permission of Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd (Current as at 12 / 19), [Dataset – Rail_Centre_Line, Oct 2015] provided with the permission of QR Limited and other state government datasets Disclaimer: While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this data, Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd and/or the State of Queensland and/or QR Limited makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E Badu Island TORRES STRAIT ISLAND Daintree TORRES STRAIT ISLANDS ! REGIONAL COUNCIL PAPUA NEW DAINTR CAIRNS REGION Bramble Cay EE 0 4 8 12162024 p 267 Sue Islet 6 GUINEA 5 RIVE Moa Island Boigu Island 5 R Km 267 Cape Kimberley k Anchor Cay See inset for details p Saibai Island T Hawkesbury Island Dauan Island he Stephens Island ben Deliverance Island s ai Es 267 as W pla 267 TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL 266 p Wonga Beach in P na Turnagain Island G Apl de k 267 re 266 k at o Darnley Island Horn Island Little Adolphus ARAFURA iction Line Yorke Islands 9 Rd n Island Jurisd Rennel Island Dayman Point 6 n a ed 6 li d -

Great Barrier Reef

PAPUA 145°E 150°E GULF OF PAPUA Dyke NEW GUINEA O Ackland W Bay GREAT BARRIER REEF 200 E Daru N S General Reference Map T Talbot Islands Anchor Cay A Collingwood Lagoon Reef N Bay Saibai Port Moresby L Reefs E G Island Y N E Portlock Reefs R A Torres Murray Islands Warrior 10°S Moa Boot Reef 10°S Badu Island Island 200 Eastern Fields (Refer Legend below) Ashmore Reef Strait 2000 Thursday 200 Island 10°40’55"S 145°00’04"E WORLD HERITAGE AREA AND REGION BOUNDARY ait Newcastle Bay Endeavour Str GREAT BARRIER REEF WORLD HERITAGE AREA Bamaga (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland and includes all islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas and Submerged Lands Orford Bay Act exclusions.) Total area approximately 348 000 sq km FAR NORTHERN Raine Island MANAGEMENT AREA GREAT BARRIER REEF REGION CAPE Great Detached (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland but excludes lburne Bay he Reef Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas S and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) Total area approximately 346 000 sq km ple Bay em Wenlock T GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK (Excludes Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland River G and Seas and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) Lockhart 4000 Total area approximately 344 400 sq km Weipa Lloyd Bay River R GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK 12°59’55"S MANAGEMENT AREA E 145°00’04"E CORAL SEA YORK GREAT BARRIER REEF PROVINCE Aurukun River A (As defined by W.G.H. -

WTA Corporate Plan 2020-2025

Weipa Town Authority CORPORATE PLAN 2020-2025 Contents Introduction 1 “Whatever the future Our Vision 2 Who are we? 4 direction and growth that Our Approach 5 Introduction Service Excellence 6 our community wants it will A vibrant, connected and Welcome to the Weipa Town Authority (WTA) Corporate Plan resilient community 8 not happen by accident, for 2020‑2025. This plan is the guiding document for the WTA Partnerships and collaboration 10 members and staff and directs all our planning and service delivery. A thriving, diverse economy 12 it needs to be guided and Community infrastructure 14 I want to acknowledge the traditional custodians The Weipa Port is a vital piece of transport directed, through vision of the land upon which we all live, and I pay my infrastructure as the only deep water harbour Our planning processes 16 respects to elders past, present and emerging. between Cairns and Darwin (without the Great The WTA Members 17 and commitment.” Working together we can shape the future so that it Barrier Reef). There is opportunity to re-purpose benefits all people. and diversify use of the port to ensure viability and sustainability into the future. A plan like this only comes together because of the hard work, passion and commitment of so many The continued sealing of the Peninsula people, including Rio Tinto and WTA members Development Road, the upgrade of our regional who have generously provided input, expertise airport, the installation of state-of-the-art and collaboration in the development of the WTA medical equipment (CT scanner) in Weipa are Corporate Plan 2020-2025. -

Community PLAN Respecting People, Place and Progress

DRAFT TEN YEAR Community PLAN Respecting people, place and progress Cook Shire Council | Ten Year Community Plan 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 A PAUSE FOR REFLECTION – SOME OF COUNCIL’S ACHIEVEMENTS THE PURPOSE OF THE OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS 21 TEN YEAR COMMUNITY PLAN 5 Roads 21 COUNCIL’S STRATEGIC PLANNING FRAMEWORK 5 Shortage of Jobs 21 COMMUNITY PLAN THEMES 6 Small Business Development 21 Places for People 7 Youth Issues 21 Wellbeing and Empowerment 7 Need for a Diverse Economy 22 Accessibility and Connectivity 8 Maintain Historical Aspects 22 Economic Development 8 Communications Infrastructure 22 Environmental Responsibility 11 Health Issues 22 Organisational capability 11 Liveability of Townships 22 HOW PROGRESS WILL BE Limited Aged Care 22 REPORTED AND EVALUATED 12 OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES PARTNERSHIPS 12 FOR COOK SHIRE COUNCIL 23 WHO WE ARE: Ageing Population 23 UNDERSTANDING COOK SHIRE 14 Global Political Volatility 23 Our People 15 Developing Trade Markets 23 Index of Relative Socio-economic Climate change 23 Disadvantage 15 Community and Customer Australian Early Development Census Expectations and New Technology 23 – Community Profile 2018 16 Land Tenure and Use 23 Physical Health and Wellbeing Social Competence Financial Sustainability 23 Emotional Maturity COMMUNITY CONSULTATION FEEDBACK 24 Language and Cognitive Skills Location of Respondents 24 (School-based) Age of Respondents 24 Communications Skills and General Knowledge Sex of Respondents 24 Proportion of Children Who Are Percent of Respondents who Agree Developmentally -

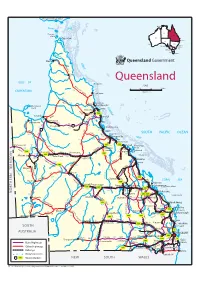

Queensland-Map.Pdf

PAPUA NEW GUINEA Darwin . NT Thursday Island QLD Cape York WA SA . Brisbane Perth . NSW . Sydney Adelaide . VIC Canberra . ACT Melbourne TAS . Hobart Weipa PENINSULA Coen Queensland Lizard Is DEVELOPM SCALE 0 10 20 300km 730 ENT Kilometres AL Cooktown DEV 705 ROAD Mossman Port Douglas Mornington 76 Island 64 Mareeba Cairns ROAD Atherton A 1 88 Karumba HWY Innisfail BURKE DY 116 Normanton NE Burketown GULF Tully DEV RD KEN RD Croydon 1 194 450 Hinchinbrook Is WILLS 1 262 RD Ingham GREGOR 262 BRUCE Magnetic Is DEV Y Townsville DEV 347 352 Ayr Home Hill DE A 1 Camooweal BURKE A 6 130 Bowen Whitsunday 233 Y 188 A Charters HWY Group BARKL 180 RD HIGHW Towers RD Airlie Beach Y A 2 Proserpine Y Cloncurry FLINDERS Richmond 246 A 7 396 R 117 A 6 DEV Brampton Is Mount Isa Julia Creek 256 O HWY Hughenden DEV T LANDSB Mackay I 348 BOWEN R OROUGH HWY Sarina R A 2 215 DIAMANTINA KENNEDY E Dajarra ROAD DOWNS T 481 RD 294 Winton DEV PEAK N 354 174 GREG A 1 R HIGHW Clermont BRUCE E KENNEDY Boulia OR 336 A A 7 H Y Y Yeppoon DEV T Longreach Barcaldine Emerald Blackwater RockhamptonHeron Island R A 2 CAPRICORN A 4 HWY HWY 106 A 4 O RD 306 266 Gladstone N Springsure A 5 A 3 HWY 389 Lady Elliot Is LANDSBOR HWY DAWS Bedourie Blackall ON Biloela 310 Rolleston Moura BURNETT DIAMANTINA OUGH RD A 2 C 352 Bundaberg A 404 R N Theodore 385 DEV A Hervey Bay R 326 Eidsvold A 1 V LEICHHARDT Fraser Is D O Windorah E Taroom N 385 V BRUCE EYRE E Augathella Maryborough L Gayndah RD HWY A 3 O DEV A 7 A 5 HWY Birdsville BIRDSVILLE 241 P M HWY A 2 E N W T ARREGO AL Gympie Quilpie -

Mineral Resource Inventory of Cape York Peninsula

NATURAL RESOURCES ANALYSIS PROGRAM (NRAP) MINERAL RESOURCE INVENTORY \ OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA T.J. Denaro Department of Minerals and Energy Queensland 1995 CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY (CYPLUS) Natural Resources Analysis Program MINERAL RESOURCE INVENTORY OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA T.J. Denaro Department of Minerals and Energy Queensland 1995 CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Qumland and Commonwealth Governments Final report on project: NR04 - MINERAL RESOURCE INVENTORY Recommended citation: Denaro, T. J. (1995). 'Mineral Resource Inventory of Cape York Peninsula'. (Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy, Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland, Brisbane, Department of the Environment, Sport and Temtories, Canberra, and Department of Minerals and Energy, Queensland, Brisbane.) Note: Due to the timing of publication, reports on other CYPLUS projects may not be fully cited in the BIBLIOGRAPHY section. However, they should be able to be located by author, agency or subject. ISBN 0 7242 6200 8 'g The State of Queensland and Commonwealth of Australia 1995. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland and the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Office of the Co-ordinator General, Government of Queensland PO Box 185 BRISBANE ALBERT STREET Q 4002 The Manager, Commonwealth Information Services GPO Box 84 CANBERRA ACT 2601 CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY STAGE I PREFACE TO PROJECT REPORTS Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy (CYPLUS) is an initiative to provide a basis for public participation in planning for the ecologically sustainable development of Cape York Peninsula.