New´ Commons for the Twenty-First Century: Innovative Legal Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Common Ground

Finding common ground Integrating local and national interests on commons: guidance for assessing the community value of common land Downley Common in the Buckinghamshire Chilterns. About this report This work was commissioned by Natural England and funded through its Ma- jor Project on Common Land. The objective of the work, as given in the work specification, is to identify mechanisms to recognise and take account of local community interests on commons, hence complementing established criteria used in assessing national importance of land for interests such as nature con- servation and landscape. The intention is not that community interests should be graded or weighed and balanced against national interests, but rather that they should be given proper recognition and attention when considering man- agement on a common, seeking to integrate local and national aspirations within management frameworks. Specifically, the purpose of the commission was to provide information to enable the user or practitioner to: i be aware of issues relating to the community interests of common land, ii assess the importance of common land to local neighbourhoods, iii engage with communities and understand their perspectives, iv incorporate community concerns in any scheme examining the future and management of commons. The advice and views presented in this report are entirely those of the Open Spaces Society and its officers. About the authors This report is produced for Natural England by Kate Ashbrook and Nicola Hodgson of the Open Spaces Society. Kate Ashbrook BSc Kate has been general secretary (chief executive) of the Open Spaces Society since 1984. She was a member of the Common Land Forum (1983-6), and the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions’ advisory group on the good practice guide to managing commons (1997-8). -

South East Walker June 2017 a Walk in the Park

SOUTH EAST No. 98 June 2017 Publicwalker path victory at Harrow ocal residents, backed by known as numbers 57 and 58 in the had argued that Harrow Council the Open Spaces Society, London Borough of Harrow, which should make the school reopen the Lthe Ramblers and Harrow have for centuries run in direct lines path, as required by law but instead Hill Trust, have defeated plans by across the land now forming part of the council chickened out and elite Harrow School to move two its grounds. agreed to allow the school to move public footpaths across its sports Footpath 57 follows a north - the path around the obstructions. pitches, all-weather pitches and south route between Football Lane Footpath 58 runs in a direct line Signs point the way from Football Lane. tennis courts. The objectors and Pebworth Road. The school between the bottom of Football fought the plans at a six-day obstructed the footpath with tennis Lane and Watford Road, and objectors represented themselves. straight towards it. The proposed public inquiry earlier this year. courts surrounded by fencing in the school applied to move it to a Appearing as objectors at the diversions are inconvenient and The government inspector, Ms 2003. For nine years, the school zigzag route to avoid the current inquiry were Kate Ashbrook of considerably longer'. Alison Lea, has now rejected the even padlocked the gates across configuration of its sports pitches. the Open Spaces Society and the Says Kate Ashbrook, General proposals. another section of the path but Alison Lea refused the proposals Ramblers, Gareth Thomas MP, Secretary of the Open Spaces Harrow School wanted to move reopened them following pressure principally because of the impact of Harrow councillor Sue Anderson, Society and Footpath Secretary for the two public footpaths, officially from the objectors. -

Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain

Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Edited by Brendan Prendiville and David Haigron Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Edited by Brendan Prendiville and David Haigron This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Brendan Prendiville, David Haigron and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4247-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4247-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ........................................................................ vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Brendan Prendiville Chapter One .............................................................................................. 17 Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain: An Overview Brendan Prendiville Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 49 The Transformation of Climate Politics in the UK Neil Carter Chapter Three .......................................................................................... -

Local Spaces Open Minds Report

Local Spaces: Open Minds Inspirational ideas for managing lowland commons and other green spaces An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Published by the Chilterns Conservation Board in March 2015 Local Spaces: Open Minds Inspirational ideas for managing lowland commons and other green spaces o CONSERVATION BOARD HITCHIN The M1 Chilterns Area of DUNSTABLE LUTON Outstanding Natural AYLESBURY Beauty TRING HARPENDEN WENDOVER HEMEL BERKHAMSTED HEMPSTEAD PRINCES RISBOROUGH CHESHAM M25 CHINNOR M40 M1 STOKENCHURCH AMERSHAM CHORLEYWOOD WATLINGTON HIGH BENSON WYCOMBE BEACONSFIELD MARLOW WALLINGFORD M40 N River Thames M25 0 5 10 km HENLEY-ON-THAMES GORING M4 0 6 miles M4 READING Acknowledgements The Chilterns Conservation Board is grateful to the Heritage Lottery Fund for their financial support from 2011 to 2015 which made the Chilterns Commons Project possible. We are also grateful to the project's 18 other financial partners, including the Chiltern Society. Finally, we would like to pay special tribute to Rachel Sanderson who guided the project throughout and to Glyn Kuhn whose contribution in time and design expertise helped to ensure the completion of the publication. Photographs: Front cover main image – Children at Swyncombe Downs by Chris Smith Back cover main image – Sledging on Peppard Common by Clive Ormonde Small images from top to bottom – Children at home in nature by Alistair Will Hazel dormouse courtesy of redorbit.com Orange hawkweed by Clive Ormonde Grazing herd, Brill Common by Roger Stone Discovering trees on a local nature reserve by Alistair Will Local Spaces: Open Minds Determining and setting out a future for key areas of open space, like the 200 commons Preface scattered across the Chilterns, is essential, but a daunting challenge for any individual. -

Natural Environment White Paper

House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee Natural Environment White Paper Written Evidence Only those submissions written specifically for the Committee and accepted by the Committee as evidence for the inquiry Natural Environment White Paper are included. 1 List of written evidence 1 British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) 2 Countryside Alliance 3 Soil Association 3A Soil Association (further submission) 4 The Open Spaces Society 4A The Open Spaces Society (further submission) 5 Landscape Institute 5A Landscape Institute (further submission) 6 British Ecological Society 7 Plantlife 7A Plantlife (further submission) 8 Food Ethics Council 9 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology 10 Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) 10A Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) (further submission) 11 Woodland Trust 11A Woodland Trust (further submission) 12 Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) 12A Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) (further submission) 13 Campaign for National Parks 14 Friends of the Earth England 15 London Wildlife Trust 16 Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT), the Farming & Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG) and Linking Environment and Farming (LEAF) 17 English Heritage 18 Field Studies Council 19 Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) 19A Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) (further submission) 20 Local Government Association (LGA) 20A Local Government Association (LGA) (further submission) 21 Food and Drink Federation 22 National Farmers’ Union (NFU) 22A -

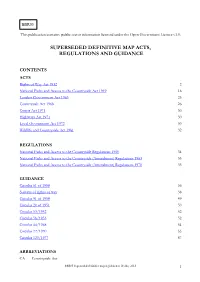

BBR05 Definitive Maps Historical

BBR05 This publication contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. SUPERSEDED DEFINITIVE MAP ACTS, REGULATIONS AND GUIDANCE CONTENTS ACTS Rights of Way Act 1932 2 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 16 London Government Act 1963 25 Countryside Act 1968 26 Courts Act 1971 30 Highways Act 1971 30 Local Government Act 1972 30 Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 32 REGULATIONS National Parks and Access to the Countryside Regulations 1950 34 National Parks and Access to the Countryside (Amendment) Regulations 1963 35 National Parks and Access to the Countryside (Amendment) Regulations 1970 35 GUIDANCE Circular 81 of 1950 36 Surveys of rights of way 38 Circular 91 of 1950 49 Circular 20 of 1951 50 Circular 53/1952 52 Circular 58/1953 52 Circular 44/1968 54 Circular 22/1970 55 Circular 123/1977 57 ABBREVIATIONS CA Countryside Act BBR05 Superseded definitive map legislation at 20 May 2013 1 ACTS This transcript has been made available with the permission of the Open Spaces Society as copyright holder. The text of the Rights of Way Act 1932 is public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. THE COMMONS, OPEN SPACES AND FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY THE RIGHTS OF WAY ACT, 1932 (with special reference to the functions of Local Authorities thereunder) ITS HISTORY AND MEANING By Sir Lawrence Chubb THE TEXT OF THE ACT WITH A COMMENTARY By Humphrey Baker, MA, Barrister-at-Law Reprinted with revisions from the Journal of the Society for October, 1932 First Revision - -

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement Robyn M. Curtis August 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University Thesis Certification I declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History at the Australian National University, is wholly my own original work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged and has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Robyn M. Curtis Date …………………… ………………… Abstract During the second half of the nineteenth century, England became the most industrialised and urbanised nation on earth. An expanding population and growing manufacturing drove development on any available space. Yet this same period saw the origins of a movement that would lead to the preservation and creation of green open spaces across the country. Beginning in 1865, social reforming groups sought to stop the sale and development of open spaces near metropolitan centres. Over the next thirty years, new national organisations worked to protect and develop a variety of open spaces around the country. In the process, participants challenged traditional land ownership, class obligations and gender roles. There has been very little scholarship examining the work of the open space organisations; nor has there been any previous analysis of the specific membership demographics of these important groups. This thesis documents and examines the four organisations that formed the heart of the open space movement (the Commons Preservation Society, the Kyrle Society, the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association and the National Trust). It demonstrates connections between philanthropy, gender and space that have not been explored previously. -

Market Research Report Stages 1 and 2 Town and Village Greens Project

Town and Village Greens Project Market Research Report Stages 1 and 2 Prepared for: John Powell Defra Sustainable Land Use Division 5B/E Ergon House Horseferry Road London SW1P 2AL Prepared by: Diane Simpson ADAS UK Ltd Woodthorne Wergs Road Wolverhampton WV6 8TQ Date: April 2006 Copyright The proposed approach and methodology is protected by copyright and no part of this document may be copied or disclosed to any third party, either before or after the contract is awarded, without the written consent of ADAS. 0936648 Town and Village Greens Report Executive Summary 1. Introduction In April 2005 ADAS were commissioned by Defra to undertake a research survey of Town and Village Greens within England and Wales. The three main objectives were to: • Review and update existing data on greens • Identify and analyse conflicts of interest occurring in relation to the registration of new greens • Analyse the problems arising over the use and management of greens including vehicular access and parking 2. Method The survey was conducted in two stages. Stage one addressed the first of the project objectives and comprised three elements. Firstly a review of literature on greens and summary of the issues raised; secondly an analysis of the Defra database of greens registered pre 1993 and thirdly an email survey amongst Commons Registration Authorities to provide an update on the number of greens applied for and registered since 1993. Stage 2 involved a series of in depth face to face and telephone interviews. Commons Registration Officers and Council solicitors were consulted to provide an understanding of registration issues, whilst Parish Councillors were interviewed to explore the issues associated with the management of greens. -

Commons, Heaths and Greens in Greater London Report (2005)

RESEARCH REPORT SERIES no. 50-2014 COMMONS, Heaths AND GREENS IN greater LONDON Report (2005) David Lambert and Sally Williams, The Parks Agency 1 Research Report Series 50- 2014 COMMONS HEATHS AND GREENS IN GREATER LONDON REPORT (2005) David Lambert and Sally Williams, The Parks Agency © English Heritage ISSN 2046-9802 (Online) The Research Report Series incorporates reports by the expert teams within the Investigation & Analysis Division of the Heritage Protection Department of English Heritage, alongside contributions from other parts of the organisation. It replaces the former Centre for Archaeology Reports Series, the Archaeological Investigation Report Series, the Architectural Investigation Report Series, and the Research Department Report Series. Many of the Research Reports are of an interim nature and serve to make available the results of specialist investigations in advance of full publication. They are not usually subject to external refereeing, and their conclusions may sometimes have to be modified in the light of information not available at the time of the investigation. Where no final project report is available, readers must consult the author before citing these reports in any publication. Opinions expressed in Research Reports are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of English Heritage. Requests for further hard copies, after the initial print run, can be made by emailing: [email protected] or by writing to: English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Road, Eastney, Portsmouth PO4 9LD Please note that a charge will be made to cover printing and postage. Front Cover: Tooting Common, 1920-1925. Nigel Temple postcard collection. -

National Trust Annual Report 2020/21

National Trust Annual Report 2020/21 National Trust Annual Report 2020/21 1 The National Trust in brief Our purpose To look after special places throughout England, Wales and Northern Ireland for everyone, for ever. About us In 1895, our founders, Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley, pledged to preserve our historical and natural places. Their aim was not only to save important sites, but to open them up for everyone to enjoy. From this trio of environmental pioneers, the National Trust was created – and their original values are still at the heart of everything we do 125 years later. As Europe’s largest conservation charity, we look after special places for the nation to enjoy. We rely on our millions of members, volunteers, staff and supporters. Without your help, we wouldn't be able to protect the miles of coastline, woodland and countryside, and the hundreds of historic buildings, gardens and precious collections that are in our care. The National Trust cares for: • more than 500 historic houses, castles, parks, and gardens • more than one million items in our collections • more than 250,000 hectares of land • more than 780 miles of coastline This Annual Report can also be viewed online at www.nationaltrustannualreport.org.uk The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty is a registered charity (no. 205846). It is incorporated and has powers conferred on it by Parliament through the National Trust Acts 1907 to 1971 and under the Charities (National Trust) Order 2005. The Trust is governed by a Board of Trustees whose composition appears on page 48. -

National Trust Co-Founder Honoured at Westminster Abbey

National Trust co-founder honoured at Westminster Abbey Released on: October 23, 2012, 10:27 am Author: The National Trust Industry: Environment October 23, 2012, 10:27 am -- /EPR NETWORK/ -- Octavia Hill, leading social reformer and co-founder of the National Trust, has been honoured at a service to dedicate a memorial to her at Westminster Abbey in London. One hundred years after Octavia Hill's death, a memorial stone, commissioned by theNational Trust and designed and crafted by Rory Young, has been dedicated at the service that celebrates her remarkable life. Thousands of flowers, foliage and fruit from National Trust gardens across the South West were incorporated in eight spectacular displays for the service. Conceived by Mike Calnan, head of gardens at the Trust, the dramatic arrangements were made and assembled by London based floral artist Rebecca Louise Law, daughter of one of the Trust's head gardeners, together with Abbey florist, Jane Rowton-Lee. National Trust Chairman, Simon Jenkins, and Director-General, Dame Fiona Reynolds, broadcaster Julia Bradbury and writer Robert Macfarlane were among the members, supporters, staff and volunteers from the National Trust and other organisations who paid tribute to Octavia Hill with readings and prayers at the service conducted by The Very Reverend Dr John Hall, Dean of Westminster. The memorial stone, measuring 600mm x 600mm, is made of Purbeck marble, and has been laid in the nave of Westminster Abbey. Octavia Hill founded the National Trust in 1895 with Sir Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley. They were concerned about the impact of uncontrolled development and industrialisation and set up the Trust 'for the protection of the public interests in the open spaces of the country.' Octavia Hill also played a pivotal role in the housing reform movement and had a lifelong passion for learning and welfare. -

Museum of English Rural Life Page 1 Of

Museum of English Rural Life THE OPEN SPACES SOCIETY SR OSS Records of the Open Spaces Society The Collection covers the year’s 1808 - 1967. The physical extent of the collection is 7 series. Introduction Lord Eversley, the former Liberal MP and minister, founded the Commons Preservation Society in 1865. The aim of the society was to save London commons for the enjoyment and recreation of the public. Its committee members included such important figures as Octavia Hill, the social reformer, Sir Robert Hunter, solicitor and later co-founder of the National Trust, Professor Huxley and the MP's Sir Charles Dilke and James Bryce. Most of the society's members initially came from the south east, so their interests focused on London. In 1899 the Commons Preservation Society amalgamated with the National Footpaths Society, adopting the title Commons Open Spaces Society and Footpath Preservation Society. The shortened name, Open Spaces Society was adopted in the 1980's. The society promoted important pieces of legislation, including the Commons Act of 1876 and 1899. Today it's principal task is advising local authorities, commons committees, voluntary bodies, and the general public on the appropriation of commons and other open spaces. It also scrutinises applications that affect public rights of way. It has no branch organisation but works with local and regional bodies. It's membership, therefore, is small. The society also publishes a quarterly journal as well as a wide variety of literature. SR OSS AD ADMINISTRATIVE RECORDS SR OSS AD1 Minutes Page 1 of 169 Museum of English Rural Life SR OSS Minutes, Joint Committee, Commons Preservation Society and AD1/1 the Ramblers' Association, Public Paths Sub-Committee, 1950; Central Rights of Way Committee 1950-1956 Bound volume SR OSS CO LEGAL RECORDS SR OSS CO7 Records of court action SR OSS Earl Brownlow v Smith.