A New Chapter. Shifting Poland Towards Net-Zero Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Pride and Prejudice : Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden

Pride and Prejudice Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Anna Malmquist Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 Linköping University Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping 2015 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 At the Faculty of Arts and Science at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Division of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning. Distributed by: Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping University SE - 581 83 Linköping Anna Malmquist Pride and Prejudice: Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Cover painting: Kristin Winander Upplaga 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7519-087-7 ISSN 0282-9800 ISSN 1654-2029 ©Anna Malmquist Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, 2015 Printed by: LiU-tryck, Linköping 2015 To my children, Emil, Nils, Myran and Tove Färgen på barns ögon kommer från arvet, glittret i barns ögon kommer från miljön. The colour of children’s eyes comes from nature, the sparkle in children’s eyes comes from nurture. Abstract Options and possibilities for lesbian parents have changed fundamentally since the turn of the millennium. A legal change in 2003 enabled a same-sex couple to share legal parenthood of the same child. An additional legal change, in 2005, gave lesbian couples access to fertility treatment within public healthcare in Sweden. -

Owner's Manual. Mini Hardtop 2 Door / 4 Door

LINK: CONTENT & A-Z OWNER'S MANUAL. MINI HARDTOP 2 DOOR / 4 DOOR. Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 WELCOME TO MINI. OWNER'S MANUAL. MINI HARDTOP 2 DOOR / 4 DOOR. Thank you for choosing a MINI. The more familiar you are with your vehicle, the better control you will have on the road. We therefore strongly suggest: Read this Owner's Manual before starting off in your new MINI. It contains important information on vehicle operation that will help you make full use of the technical features available in your MINI. The manual also contains information designed to enhance operating reliability and road safety, and to contribute to maintaining the value of your MINI. Any updates made after the editorial deadline can be found in the appendix of the printed Owner's Manual for the vehicle. Get started now. We wish you driving fun and inspiration with your MINI. 3 Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTES Information............................................................................................................................10 QUICK REFERENCE Entering..................................................................................................................................20 Set-up and use.......................................................................................................................23 On the road........................................................................................................................... -

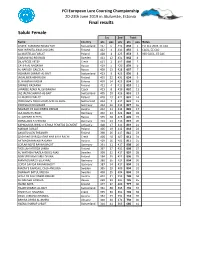

FCI European Lure Coursing 2019 Total Results.Xlsx

FCI European Lure Coursing Championship 20‐23th June 2019 in Jõulumäe, Estonia Final results Saluki Female 1st2nd Total Name Country pts pos pts pts pos Notes CHAYA' ASMAANII NESSA'YAH Switzerland 417 6 441 858 1 FCI ECC 2019, EE CAC NOX INFINITA ANAS DISCORS Finland 422 3 433 855 2 CACIL, EE CAC LA MARTELLA FARLAT Poland 428 1 425 853 3 RES‐CACIL, EE CAC GARAMIYAS ROUNAQ Sweden 411 12 431 842 4 DILAFROZE YRTEP Czech 423 2 417 840 5 CATIFA AL NAQAWA Russia 419 5 420 839 6 AL NAFISEH CALEELA Russia 409 15 428 837 7 INSHIRAH SHARAF‐AL‐BAIT Switzerland 413 9 423 836 8 JAISALMER ABHIRUCHI Finland 403 22 431 834 9 EL HAMRAH NADIIR Estonia 409 14 425 834 10 ZARABIS RAZAANA Finland 421 4 412 833 11 LARABEE AZADI AL DJIIBAAJAH Czech 413 8 419 832 12 JAZ JALIYA SHARAF‐AL‐BAIT Switzerland 405 20 426 831 13 LA MAREA FARLAT Poland 410 13 421 831 14 PIROUHETE PARU‐SIYATI‐MIN AL ASIFE Netherland 414 7 417 831 15 PADESAH FEROÚZADE Germany 413 10 414 827 16 NASIRAH OF FALCONERS DREAM Austria 412 11 414 826 17 JAA´BANU EL RIAD Germany 402 24 422 824 18 AL NAFISEH ELEEZA Russia 395 28 425 820 19 OONA‐ZIVA Y‐SHIRVAN Germany 403 23 416 819 20 KAPADOKIJA WIND CHERGUI PENKTAS ELEMENT Lithuania 408 17 411 819 21 MARAM FARLAT Poland 406 19 412 818 22 AAVATUULEN THEANOR Finland 398 26 417 815 23 QASHANG DAR QUADAR HAR KALA RACHI Czech 406 18 407 813 24 AR´MAGHAAN ALIYA KIANA Austria 409 16 402 811 25 CEYLAN NEFIZ RAVAN BACHT Germany 391 31 417 808 26 TAZILLAH AFROZA LAMIA Finland 397 27 411 808 27 AL WATHBA FAAZILA OBI EL‐MAS Sweden 390 32 417 807 28 NON SERVIAM -

URBANITIES Journal of Urban Ethnography

URBANITIES Journal of Urban Ethnography ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ ̶ Volume 9 · Number 1 · May 2019 Urbanities, Vol. 9 · No 1 · May 2019 © 2019 Urbanities Editors: Copyright © 2019 Urbanities Urbanities grants free and unrestricted access to the Italo Pardo, University of Kent, U.K. journal’s content for scientific, educational, non- Jerome Krase, Brooklyn College, commercial and non-promotional purposes. All City University of New York, U.S.A. peer-reviewed articles and other authored contributions are protected by copyright. Users may Assistant Editor: crawl articles for indexing and may access or James Rosbrook-Thompson, Anglia Ruskin download the full text of a contribution provided University, Cambridge, U.K. that: (i) the authors’ rights, including the rights to Book Reviews Editor: ‘paternity’ (also known as ‘attribution’) and ‘integrity’, are not compromised and are properly Daina Cheyenne Harvey, College of the Holy acknowledged; (ii) if an article/contribution content Cross, Worcester, MA, U.S.A. is copied, downloaded or otherwise reused for non- commercial research and education purposes, a link Film and Video Reviews Editor: to the appropriate bibliographic citation (authors, Alex Vailati, Federal University of Pernambuco, article title, journal, volume, issue, page numbers, Brazil and the link to the definitive published version on Urbanities’ platform/URL) should be provided; (iii) Scientific Board: if an article/contribution content is posted to other Janaki Abraham, Delhi University, India repositories, a link to the definitive published version Robyn Andrews, Massey University, New Zealand of the article on Urbanities’ platform/URL is Gary Armstrong, City, University of London, U.K. -

Children Living in Precarious Family Situations (2019)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Directorate C — Social Affairs Unit C.3 — Disability & inclusion European Commission B-1049 Brussels Contact: Julius op de Beke ([email protected]) EUROPEAN COMMISSION Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee Target Group Discussion Paper on Children living in Precarious Family Situations 2019 José-Manuel Fresno, Stefan Meyer and Skye Bain Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion 2019 In 2015, the European Parliament called on the European Commission and the European Union Member States ‘to introduce a Child Guarantee so that every child in poverty can have access to free healthcare, free education, free childcare, decent housing and adequate nutrition, as part of a European integrated plan to combat child poverty’. Following the subsequent request by the Parliament to the Commission to implement a Preparatory Action to explore the potential scope of a Child Guarantee for vulnerable children, the Commission commissioned a study to analyse the feasibility of such a scheme. The Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee (FSCG) is carried out by a consortium consisting of Applica and the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER), in close collaboration with Eurochild and Save the Children, and with the support of nine thematic experts, 28 country experts and an independent study editor. For more information on the Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee, see: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1428&langId=en. LEGAL NOTICE Manuscript completed in 2019 Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. -

Social Dialogue in Face of Changes on the Labour Market in Poland

Professor Jacek P. Męcina (prof. UW dr hab.), is a lawyer and a political scientist, as well as a social policy expert on labour law, employment relations, employment policy, and social dialogue. His research interests JACEK M are focused on employment and labour market policy, labour law, and collective labour relations, the conditions of functioning of social dialogue JACEKJACEK MMĘĘCINACINA in Poland and in the European countries. Professor at the Institute of Social Policy, the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Warsaw, since 2016 Director of the Institute of Social Policy. Scholar of the European Programme TEMPUS and the Alexander von Hum- Social Dialogue boldt Foundation. A member of the Scientifi c Council of the academic journals — Human Resource Management and Social Dialogue and Social Ę in Face of Changes Policy. The Author of more than 100 books, articles, and papers on labour law, labour relations, social CINA in Face of Changes dialogue, employment and labour market issues. He cooperates with the European institutions, the ILO, and many academic and research centres in Poland, Germany and other European countries. on the Labour Market Poland has been building its market economy for slightly more than a quarter of a century and has been a member of the European Union for thirteen years. Currently, Poland can feel the results of the in Poland. international crisis, but with some delay compared to the other European countries. Despite its stable Crisis to Breakthrough From of Changes on the Labour Social Dialogue in Face Market in Poland. economic development and relatively low unemployment, a deterioration in the quality of labour From Crisis relations is noticeable, and what is more Poland recorded a rapid increase in such forms of atypical employment and fi xed-term employment, reaching the highest levels among the EU countries. -

Download.Xsp/WMP20100280319/O/M20100319.Pdf (Last Accessed 15 April 2018)

Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity Local Communities, Religion and Historical Politics Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Cover image: © Dariusz Bogumił This project was supported by the National Science Centre in Poland grant no. DEC-2013/09/D/HS6/02630. English translation and editing by Philip Palmer Reviewed by Marta Kurkowska-Budzan, Jagiellonian University ISSN 2191-3528 ISBN 978-3-631-67300-3 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-06509-1 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70830-9 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70831-6 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b15596 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper, 2019 Peter Lang –Berlin ∙ Bern ∙ Bruxelles ∙ New York ∙ Oxford ∙ Warszawa ∙ Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Acknowledgments Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Working Papers Reception Policies, Practices and Responses Poland

Working Papers Global Migration: Consequences and Responses Paper 2020/45, March 2020 Reception Policies, Practices and Responses Poland Country Report Marta Pachocka, Konrad Pędziwiatr, Karolina Sobczak-Szelc, Justyna Szałańska Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw © Marta Pachocka, Konrad Pędziwiatr, Karolina Sobczak-Szelc, Justyna Szałańska Reference: RESPOND Deliverable 4.1. This research was conducted under the Horizon 2020 project ‘RESPOND Multilevel Governance of Mass Migration in Europe and Beyond’ (#770564). This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the RESPOND Project consortium authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The European Union is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Suggested citation: Pachocka, M., Pędziwiatr, K., Sobczak-Szelc, K., Szałańska, J. (2020). ‘Reception Policies, Practices and Responses. Poland – Country Report’, Multilevel Governance of Mass Migration in Europe and Beyond Project (#770564, Horizon2020) Report Series, Available at: https://www.respondmigration.com/wp-blog/. This document is available for download at: www.respondmigration.com Horizon 2020 RESPOND: Multilevel Governance of Mass Migration in Europe and Beyond (770564) 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 List of figures 6 List of Tables 7 List of Abbreviations 8 About the Project 9 Executive Summary 10 Introduction 13 Methodology and Sources 15 1. Legal Regulations and Policies of Reception: A Multi-level Perspective 27 1.2. -

Merry Christmas Wesołych Świąt

“Together – We Can and We Will” ZGODA THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE OF THE U.S. OF N.A. The officialPOLISH Publication NATIONAL of ALLIANCE the Polish WINTER 2019 www.pna-znp.orgNational Alliance of North America1881-2019 Vol. 161; No. 4 Merry Christmas Wesołych Świąt 3 President’s Corner (USPS 699-120) Published Quarterly 4 From the Editor The Official Publication 5 Christmas Greetings of the Polish National Alliance 6 – 8 From the Manager of Sales 6100 N. Cicero Avenue Chicago, IL 60646-4385 9 – 37 Fraternal News & Activities Phone: (773) 286-0500 • Scholarship Opportunities Fax: (773) 286-0842 • 110th Anniversary of Lodge 1052 • District XII Annual Convention www.pna-znp.org • Henry Kotroba Hall in Dudley, MA Polish National Alliance • Frank Zielinski Pavilion in Wallington, CT of US of NA • Running for an Independent Poland • We are Proud of Executive Committee • 2019 Photo Contest Winners Frank J. Spula • New Members President • District XIII Events Marian Grabowski • Region “H” News Vice President • Polish Heritage Month in Chicago • Polish Heritage Month in Boston Alicja Kuklinska • PNA ‘s Legal Clinic 2020 Schedule National Secretary 38 – 45 Life of Polonia Steve H. Tokarski • Legion of the Young Polish Women Anniversary Treasurer • PAC Golden Jubilee • Council 84 Veterans Remembrance Send all articles, correspondence • 50 Years of Joseph Conrad Yacht Club and materials to: • PAC Western Massachusetts Heritage Banquet ZGODA Magazine 6100 N. Cicero Avenue 46 – 48 Living Well – Loneliness Chicago, IL 60646 49 In Memoriam Alicja Kuklinska 50– 54 Destination Poland – Splendor of Podlasie Editor 55 Polish Traditions Beatrice Jędrycha Assistant Editor 56 – 57 History Pages – The Queen of Polish Carols Contents Ewa Krutul 58 – 59 Taste of Poland – Podlasie Specialties Graphic Designer 60 Bulletin Board e-mail: [email protected] 61 Dziennik Zwiazkowy Periodicals–Postage Paid at Chicago, 62 WPNA 103.1 FM Illinois and additional mailing offices. -

Initial Coin Offerings (Icos) for SME Financing

Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) for SME Financing │ 2 Please cite this publication as: OECD (2019), Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) for SME Financing, www.oecd.org/finance/initial-coin-offerings-for-sme-financing.htm This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. © OECD 2019 │ 3 Foreword Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLT) like blockchain are a relatively recent arrival in the world of finance, but are already driving new forms of financial innovation, new breeds of financial products, and creating new processes and platforms. Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) are one of the most prominent applications of blockchain for finance, allowing for an innovative and inclusive way of financing for small and medium-sized companies (SMEs). Over the past two years the use of ICOs has gone from ‘too small to care’ to ‘too big to ignore’ for markets and regulators alike. Much of the discourse around ICOs to date has focused on the uncertainty of the applicable regulatory framework for ICOs and crypto-asset markets. This report takes the analysis further, discussing “tokenomics” and limitations in ICO structuring which can give rise to conflicts of interest and expose investors to significant risks. It analyses issues around valuation, accounting and allocation of value, as well as trading of tokens. -

The Revenge of the Nation: Political Passions in Contemporary Poland

THE REVENGE OF THE NATION POLITICAL PASSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY POLAND ▪ AZILIZ GOUEZ REPORTREPORT NO. NO. 116 117 ▪ ▪NOVEMBER JANUARY 20192018 ISSN 2257-4840 #POLAND THE REVENGE OF THE NATION POLITICAL PASSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY POLAND AZILIZ GOUEZ ASSOCIATE RESEARCH FELLOW, JACQUES DELORS INSTITUTE AZILIZ GOUEZ TABLE OF CONTENTS Aziliz Gouez is an anthropologist by training, with an interest in issues of identity, memory and political symbolism. Between 2013-2017 she was the Chief Speechwriter for the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins. As a Research Fellow at the Jacques Delors Institute from 2005 to 2010 she directed a research Executive summary 5 programme on the predicaments of European identity in the post-1989 era, looking in particular at the discrepancy between economic integration, East-West migration of labour and capital on the one hand, Introduction 7 and political and cultural patterns on the other. Aziliz is a graduate of Sciences Po Paris, the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and the 1. Social policy for good people 10 University of Cambridge. She has lived and worked in Romania, Poland, Ireland, the former-Yugoslavia, as well as the United States and Israel. Recently, she has published on the consequences of Brexit for 1.1 The 2018 local elections and the battle for the Polish province 10 Ireland; she currently steers a project on populism for the Dublin-based IIEA while also contributing to the development of the network of Pascal Lamy Chairs of European anthropology. 1.2 “Good change”: redistribution, family and the active state 13 1.3 “We are not servants, we aspire to more” 16 2.