1 Re-Approaching the Social Dimensions of the Irish Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

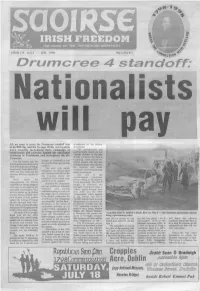

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

Military Archives Cathal Brugha Bks Rathmines Dublin 6 ROINN

Military Archives Cathal Brugha BKs Rathmines Dublin 6 ROINN C0SANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 316 Witness Mr. Peter Folan, 134 North Circular Road, Dublin. Identity Head Constable 1913 - 1921. R.I.C. Aided Irish Volunteers and I.R.A. by secret information. Subject (a) Duties as reporter of Irish meetings; (b) Dublin Castle Easter Week 1916 and events from that date to 1921.miscellaneous Conditions, if any, stipulated by Witness Nil File No. S.1431 Form Military Archives Cathal Brugha BKs Rathmines Dublin 6 STATEMENT BY PETER FOLAN (Peadar Mac Fhualáin) Bhothar Thuaidh, 134 Chuar Blá Cliath. I reported several meetings throughout the country. I was always chosen to attend meetings which were likely to be addressed by Irish speakers. Previously, that is from 1908 Onwards, I attended meetings that were addressed by Séamus ó Muilleagha, who was from East Galway and used to travel from County to County as Organiser of the Gaelic League. I was a shorthand reporter and gave verbatim reports of all speakers. Sèamus, in addition to advocating the cause of the language, advised the people that it was a scandal to have large ranches in the possession of one man while there were numbers of poor men without land. He advocated the driving of the cattle off the land. Some time after the meetings large cattle drives took place in the vicinity, the cattle being hunted in all directions. When he went to County Mayo I was sent there and followed him everywhere he announced a meeting. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

BMH.WS1721.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1721. Witness Seumas Robinson 18 Highfield Foad, Rathgar, Dublin. Identity. O/C. South Tipperary Brigade. O/C. 2nd Southern Division, I.R.A. Member of Volunteer Executive. Member of Bureau of Military History. Subject. Irish Volunteer activities, Dublin, 1916. I.R.A.activities, Tipperary, 1917-1921 Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.132. Form BSM2 SEUMASROBINSON. 1902. Joined the first Fianna (Red Branch Knights); founded by Bulmer Hobson in 1902, Belfast. 1902. Joined "Oscar" junior hurling club, Belfast. 1903. Joined Gaelic League, Glasgow. 1913. December. Joined the Irish Volunteers, (Glasgow. 1916. January. Attached to Kimmage Garrison. 1916. Easter Week. Stationed i/c. at Hopkins & Hopkins, O'Connell Street (Bride). 1916. May. Interned Richmond Barracks (one week), Stafford Gaol, Frongoch, Reading Gaol. Released Christmas Day, 1916. 1917. February. Assisted in reorganising the Volunteers in Tipperary. l9l8. October, Elected Brigadier, South Tipperary Brigade. 1920. Elected T.D. to Second Dáil, East Tipperary and Waterford. 1921. November December. Appointed O/C., 2nd Southern Division, I.R.A., in succession to E. O'Malley. 1922. Elected Member of Volunteer Executive. l928. Elected Senator. 1935. January. Appointed Member of M.S.P. Board. l949. Appointed Member, Bureau of Military History. 1953. (?) Appointed Member of Military Registration Board. STATEMENTBY Mr. SEUMASROBINSON, 18, Highfield Road, Rathgar, Dublin. - Introduction - "A SOLDIER OF IRELAND" REFLECTS. Somewhere deep in the camera (or is it the anti-camera) of my cerebrum (or is it my cerebellum"), whose loci, by the way, are the frontal lobes of the cranium of this and every other specimen of homo-sapiens - there lurks furtively and nebulously, nevertheless positively, a thing, a something, a conception (deception'), a perception, an inception, that the following agglomeration of reminiscences will be "my last Will and Testament". -

Going Against the Flow: Sinn Féin´S Unusual Hungarian `Roots´

The International History Review, 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1, 41–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879913 Going Against the Flow: Sinn Fein’s Unusual Hungarian ‘Roots’ David G. Haglund* and Umut Korkut Can states as well as non-state political ‘actors’ learn from the history of cognate entities elsewhere in time and space, and if so how and when does this policy knowledge get ‘transferred’ across international borders? This article deals with this question, addressing a short-lived Hungarian ‘tutorial’ that, during the early twentieth century, certain policy elites in Ireland imagined might have great applicability to the political transformation of the Emerald Isle, in effect ushering in an era of political autonomy from the United Kingdom, and doing so via a ‘third way’ that skirted both the Scylla of parliamentary formulations aimed at securing ‘home rule’ for Ireland and the Charybdis of revolutionary violence. In the political agenda of Sinn Fein during its first decade of existence, Hungary loomed as a desirable political model for Ireland, with the party’s leading intellectual, Arthur Griffith, insisting that the means by which Hungary had achieved autonomy within the Hapsburg Empire in 1867 could also serve as the means for securing Ireland’s own autonomy in the first decades of the twentieth century. This article explores what policy initiatives Arthur Griffith thought he saw in the Hungarian experience that were worthy of being ‘transferred’ to the Irish situation. Keywords: Ireland; Hungary; Sinn Fein; home rule; Ausgleich of 1867; policy transfer; Arthur Griffith I. Introduction: the Hungarian tutorial To those who have followed the fortunes and misfortunes of Sinn Fein in recent dec- ades, it must seem the strangest of all pairings, our linking of a party associated now- adays mainly, if not exclusively, with the Northern Ireland question to a small country in the centre of Europe, Hungary. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

Robert John Lynch-24072009.Pdf

THE NORTHERN IRA AND THE EARY YEARS OF PARTITION 1920-22 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling. ROBERT JOHN LYNCH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DECEMBER 2003 CONTENTS Abstract 2 Declaration 3 Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Chronology 6 Maps 8 Introduction 11 PART I: THE WAR COMES NORTH 23 1 Finding the Fight 2 North and South 65 3 Belfast and the Truce 105 PART ll: OFFENSIVE 146 4 The Opening of the Border Campaign 167 5 The Crisis of Spring 1922 6 The Joint-IRA policy 204 PART ILL: DEFEAT 257 7 The Army of the North 8 New Policies, New Enemies 278 Conclusion 330 Bibliography 336 ABSTRACT The years i 920-22 constituted a period of unprecedented conflct and political change in Ireland. It began with the onset of the most brutal phase of the War of Independence and culminated in the effective miltary defeat of the Republican IRA in the Civil War. Occurring alongside these dramatic changes in the south and west of Ireland was a far more fundamental conflict in the north-east; a period of brutal sectarian violence which marked the early years of partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland. Almost uniquely the IRA in the six counties were involved in every one of these conflcts and yet it can be argued was on the fringes of all of them. The period i 920-22 saw the evolution of the organisation from a peripheral curiosity during the War of independence to an idealistic symbol for those wishing to resolve the fundamental divisions within the Sinn Fein movement which developed in the first six months of i 922. -

Palestine in Irish Politics a History

Palestine in Irish Politics A History The Irish State and the ‘Question of Palestine’ 1918-2011 Sadaka Paper No. 8 (Revised edition 2011) Compiled by Philip O’Connor July 2011 Sadaka – The Ireland Palestine Alliance, 7 Red Cow Lane, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Ireland. email: [email protected] web: www.sadaka.ie Bank account: Permanent TSB, Henry St., Dublin 1. NSC 990619 A/c 16595221 Contents Introduction – A record that stands ..................................................................... 3 The ‘Irish Model’ of anti-colonialism .................................................................... 3 The Irish Free State in the World ........................................................................ 4 The British Empire and the Zionist project........................................................... 5 De Valera and the Palestine question ................................................................. 6 Ireland and its Jewish population in the fascist era ............................................. 8 De Valera and Zionism ........................................................................................ 9 Post-war Ireland and the State of Israel ............................................................ 10 The UN: Frank Aiken’s “3-Point Plan for the Middle East” ................................ 12 Ireland and the 1967 War .................................................................................. 13 The EEC and Garret Fitzgerald’s promotion of Palestinian rights ..................... 14 Brian Lenihan and the Irish -

By Richard English O'malley, Ernest Bernard

O'Malley, Ernest Bernard (‘Ernie’) by Richard English O'Malley, Ernest Bernard (‘Ernie’) (1897–1957), revolutionary and writer, was born 26 May 1897 in Ellison St., Castlebar, Co. Mayo, second child among nine sons and two daughters of Luke Malley, solicitor's clerk, of Co. Mayo, and Marion Malley (née Kearney) of Co. Roscommon. Christened Ernest Bernard Malley, his adoption of variations on this name (Earnán O Máille, Earnán O'Malley, and, most commonly, Ernie O'Malley), reflected his enthusiasm for a distinctively Irish identity – an enthusiasm that lay at the heart of his republican career and outlook. In 1906 his family moved to Dublin, where O'Malley attended the CBS, North Richmond St. In 1915 he began to study medicine at UCD. Having initially intended to follow his older brother into the British army, O'Malley in fact joined the Irish Volunteers in the wake of the 1916 Easter rising (as a member of F Company, 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade). The latter had a profound impact upon his thinking; O'Malley was to become a leading figure in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish revolution which that rebellion helped to occasion. In 1918, having twice failed his second-year university examination, O'Malley left home to commit himself to the republican cause. He was initially a Volunteer organiser with the rank of second lieutenant (under the instruction of Richard Mulcahy (qv)), operating in Counties Tyrone, Offaly, Roscommon, and Donegal. His work in 1918 involved the reorganisation, or new establishment, of Volunteer groups in the localities. Then in August 1918 he was sent to London by Michael Collins (qv) to buy arms. -

The High Tide of UK Anti-Revisionism: a History

1 HIGH TIDE Reg’s Working Class Party Throughout its history there were only a few times when the organisational skeleton of a national ML force was in the making: McCreery in the initial break from the CPGB led the first occasion. With the demise of the CDRCU, it was the launch of the CPB (ML), led by former Communist Party Executive member, Reg Birch that saw the beginnings of a national ML force unchallenged for almost a decade until the late 1970s emergence of the rejuvenated and "bolshevised" Revolutionary Communist League. For the first half of the decade, it was the CPB (ML) that seemed the most promising organisation to make a political break through. The project initiated by Reg Birch could draw upon a lot of goodwill. Birch, with a pedigree of both trade union and communist activity, offered the chance of gathering the best forces of the ML movement around the standard he had raised. Those who were already disgusted with the inward‐looking squabbling, that seemed to dominate the activities of some groups, look forward to the opportunity for serious political work in trade unions and campaigns directed at winning working class support. Reg Birch was an initial asset to the formation of the CPB (ML) and not without confidence, he announced: “Small and new as it is on the British political scene the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist Leninist) is the only party which is genuinely a workers' party. It was founded by workers, serves only the working class and is unswervingly committed to the revolutionary task of smashing capitalism and all its institutions so that exploitation can be ended and workers can establish their own socialist state."1 He had the initial support of, not only his own engineering base, but also of probably the largest single organised Marxist‐Leninist group in the country, the Association of Indian Communist, those Maoists of Indian origin resident in Britain. -

About Towards a Republic

About Towards a Republic Towards a Republic is an innovative digitisation and engagement project which opens up the archives of the National Library of Ireland to tell the story of Ireland’s journey to independence. Part of the Library’s ongoing projects marking the Irish Decade of Centenaries (1912-1923), Towards a Republic provides insights into the events and personalities that shaped the revolutionary period in Ireland. Material that has been newly digitised and catalogued for Towards a Republic includes the personal papers of Arthur Griffith, Annie O’Farrelly, Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan, Austin Stack and Laurence Ginnell, amongst many others. Further material highlights the activities of important organisations such as the Irish National Aid and Volunteers Dependents Fund which provided much needed financial support to the families of men killed or arrested during the 1916 Easter Rising. These collections offer insights into the complex events and people that shaped the later revolutionary period and Irish Civil War. The primary evidence revealed by Towards a Republic helps us to understand and contextualise the decisions, motivations and reactions of these men and women within the complicated and changing world they lived in a century ago. For example, the letters and memoirs of Kathleen Clarke, a prominent republican nationalist, recall her early life in Limerick as part of an influential Fenian family, and her meeting and later marriage to Tom Clarke, his participation in the Easter Rising and subsequent execution. Her memoirs, which are both handwritten and typescripts, detail her imprisonment in Holloway Jail and her influential political career in Sinn Féin.