The Emergence of Queer Theatre in Istanbul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Ever Happened to In-Yer-Face Theatre?

What Ever Happened to in-yer-face theatre? Aleks SIERZ (Theatre Critic and Visiting Research Fellow, Rose Bruford College) “I have one ambition – to write a book that will hold good for ten years afterwards.” Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise • Tuesday, 23 February 1999; Brixton, south London; morning. A Victorian terraced house in a road with no trees. Inside, a cloud of acrid dust rises from the ground floor. Two workmen are demolishing the wall that separates the dining room from the living room. They sweat; they curse; they sing; they laugh. The floor is covered in plaster, wooden slats, torn paper and lots of dust. Dust hangs in the air. Upstairs, Aleks is hiding from the disruption. He is sitting at his desk. His partner Lia is on a train, travelling across the city to deliver a lecture at the University of East London. Suddenly, the phone rings. It’s her. And she tells him that Sarah Kane is dead. She’s just seen the playwright’s photograph in the newspaper and read the story, straining to see over someone’s shoulder. Aleks immediately runs out, buys a newspaper, then phones playwright Mark Ravenhill, a friend of Kane’s. He gets in touch with Mel Kenyon, her agent. Yes, it’s true: Kane, who suffered from depression for much of her life, has committed suicide. She is just twenty-eight years old. Her celebrity status, her central role in the history of contemporary British theatre, is attested by the obituaries published by all the major newspapers. Aleks returns to his desk. -

In-Yer-Face Theatre İngiliz Sahnesinde Gençlik Şiddeti

604 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2019.16 (September) Youth violence on the British stage: In-yer-face theatre / B. Bağırlar (p. 604-615) Youth violence on the British stage: In-yer-face theatre Belgin BAĞIRLAR1 APA: Bağırlar, B. (2019). Youth violence on the British stage: In-yer-face theatre. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (16), 604-615. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.619333 Abstract Throughout the 1990s, British theatre shifted its focus on themes that were ever more extraordinary, and thus ever more violent. Aleks Sierz, a theatre critic, dubbed this shift ‘in-yer-face theatre’. The aim of this paper is to examine how those who had pioneered this movement, including Martin Crimp, Philip Ridley, Anthony Neilson, Judy Upton, and Moira Buffini reflect the theme of violence in youth in their plays. The overarching goal of ‘In-yer-face theatre’ is to shock viewers as well to have them come face-to-face with own inner beasts through the use of obscene language, and by means of evoking one’s inner violent instincts. In ‘In-yer-face theatre’ not only adults but also youth kill, rape, torture. Both youth and adults alike are victimized by the darkness swirling around within the pits of souls. Each playwright has her/his own way of portraying this violence on stage, Vincent River, Ghost from a Perfect Place, Ashes and Sand, Normal, Welcome to Thebes, In the Republic of Happiness. Crimp blames the emergence of violence upon capitalism. Neilson and Ridley equate violence with the struggle to stay alive. Buffini shows how ruthless youth at war can be, whilst Upton deals with the crimes committed by female gangs—a problem which had plagued much of the United Kingdom during that period. -

Mercury Fur by Philip Ridley

MERCURY FUR BY PHILIP RIDLEY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. MERCURY FUR Copyright © 2018, Philip Ridley All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of MERCURY FUR is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file- sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for MERCURY FUR are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Knight Hall Agency Ltd, 7 Mallow Street, London, EC1Y 8RQ. -

Philip Ridley and Memory

Philip Ridley and Memory Andrew Wyllie Keywords Philip Ridley; Memory; Physicality/Aurality; Nostalgia; Sexuality; British Theatre Abstract Philip Ridley’s nine plays written for an adult audience all share a concern with the role of memory and of remembering. Attempts to recuperate an authentic past by challenging an accepted, acceptable but inaccurate mythology of the past recur in the plays from The Pitchfork Disney through to Shivered. Failure to preserve the past is critiqued in some of the plays, while struggles to come to terms with the past are celebrated in others. In all the plays, the necessity of struggling to tell a story that serves to reconcile the present person with his or her past is celebrated; and the profound experience of tragic catharsis is often the object of that struggle, whether the outcome is achieved or not. In Vincent River, Mercury Fur and Leaves of Glass, the function of memory is presented in strongly contrasting ways that generate both an account of the necessity for personal and cultural memory to be retained and a critique of comforting untruths. The contrasting approaches to memory are underpinned by differing dramaturgical approaches in which either the vocal or the physical is privileged. Philip Ridley’s plays are united by a concern with memory to an extent that places the function of remembering at the centre of his output. From The Pitchfork Disney (1991) to Shivered (2012), all of his nine plays written for an adult audience deal in various ways with the role of memory in achieving or losing an adult identity. -

Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017

PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE PAID GRAND RAPIDS, MI PERMIT #1 Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017 ISBN: 978-0-8222-3542-2 DISCOUNTS See page 6 for details on DISCOUNTS for Educators, Libraries, and Bookstores 9 7 8 0 8 2 2 2 3 5 4 2 2 Bold new plays. Recipient of the Obie Award for Commitment to the Publication of New Work Timeless classics. Since 1936. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Tel. 212-683-8960 Fax 212-213-1539 [email protected] OFFICERS Peter Hagan, President Mary Harden, Vice President Patrick Herold, Secretary David Moore, Treasurer Stephen Sultan, President Emeritus BOARD OF DIRECTORS Peter Hagan Mary Harden DPS proudly represents the Patrick Herold ® Joyce Ketay 2016 Tony Award winner and nominees Jonathan Lomma Donald Margulies for BEST PLAY Lynn Nottage Polly Pen John Patrick Shanley Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017 © 2016 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. CATALOGUE 16-17.indd 1 10/3/2016 3:49:22 PM Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: A lot happened in 1936. Jesse Owens triumphed at the Berlin Olympics. Edward VIII abdicated to marry Wallis Simpson. The Hindenburg took its maiden voyage. And Dramatists Play Service was founded by the Dramatists Guild of America and an intrepid group of agents. -

Louise Jameson and Thomas Mahy Return to Star in Philip Ridley's

Louise Jameson and Thomas Mahy return to star in Philip Ridley’s acclaimed Vincent River, one of the most powerful explorations of hate crime ever written Louise Jameson and Thomas Mahy Photo Scott Rylander Louise Jameson and Thomas Mahy reprise their roles in Robert Chevara’s acclaimed production of Philip Ridley’s Vincent River, transferring to Trafalgar Studios from Park Theatre. Davey has seen something he can never forget. Anita has been forced to flee her home. Tonight, they meet for the first time... and their lives will change forever. Philip Ridley’s modern classic was a huge success when it premiered at Hampstead Theatre in 2001, and a West End smash at Trafalgar Studios in 2007. This production was seen at London’s Park Theatre in 2018. Thrilling, heartbreaking and darkly humorous by turns, it is now seen as one of the most powerful explorations of hate crime - and society’s need to crush ‘difference’ - ever written. The production will run from Thursday 16 May to Saturday 22 June. Press night: Tuesday 21 May at 7.00pm. Louise Jameson played the iconic role of assistant Leela in Dr Who opposite Tom Baker in the Seventies. She later starred in Tenko, Bergerac and EastEnders. In a 40-year career, her first love, the theatre, has seen her on stage at the National Theatre and Royal Shakespeare Company, amongst many others. Louise was nominated for an Off West End Award for her performance in Vincent River at Park Theatre. Thomas Mahy graduated from Drama Centre, London in 2017. He was also nominated for an Off West End Award for his performance in Vincent River at Park Theatre, which was his London professional debut. -

Creative Team Gemma Aked-Priestley Director

CAST Oscar Adams Robert Akodoto Curtis Jez Callum Cronin Ardan Devine Bethany Merryn Gavin, Wayne Tommy Nina Jasmín Pitt Cecilia Rodriguez Georgina Tack Stacey Alex Link If you have any enquiries regarding representation or working with any of the graduates, please contact Ed Hicks, Principal, at [email protected] Alice Unitt Christopher Watson Sarah Zak Creative Team Director Gemma Aked-Priestley Lighting Designer Rachel Sampley Set and Costume Designer Natalie Johnson Sound Designer Annie-May Fletcher Production Manager Mishi Bekesi Technical Manager Daniel Parry With thanks to: The Mill Arts Centre, Applecart Arts Gemma Aked-Priestley Director Gemma is a theatre director with a passion for new writing. Her work can be identified as emotionally daring, visually dynamic and “live”. As a woman from a working-class background the need to provide platforms for under-represented voices is embedded in the fabric of her work. Directing credits include Ripe (Nuffield Southampton Theatres, Make It So Festival 2020) My Dad’s Blind (Irish Tour 2019/ Abbey Theatre/Dublin Fringe Festival 2018, Winner of Best Production and Best Design 2018); Passing (Winner of the Theatre Royal Haymarket’s Masterclass Trust’s Pitch Your Play Award 2018, staged readings at the Theatre Royal Haymarket/Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts/The Bunker Theatre/Pleasance Theatre; The Narcissist (Flux Theatre/Hen and Chickens Theatre) Gracie (Finborough Theatre, Off West End Awards Nomination for Best Actress) and Grimm: An Untold Tale (Underbelly, Edinburgh Fringe Festival). Assistant directing credits include Mehmet Ergen on Little Miss Sunshine the Musical (Arcola Theatre); Mehmet Ergen on Stop & Search (Arcola Theatre); Sam Hodges on the world premiere and revival productions of The Shadow Factory (Nuffield Southampton Theatres); Daniel Goldman on Thebes Land (Winner of Best Production, Off West End Awards 2016, Arcola Theatre) and David Mercatali on Tonight with Donny Stixx (Bunker Theatre). -

Ridley Plays 1: the Pitchfork Disney; the Fastest Clock in the Universe; Ghost from a Perfect Place Pdf

FREE RIDLEY PLAYS 1: THE PITCHFORK DISNEY; THE FASTEST CLOCK IN THE UNIVERSE; GHOST FROM A PERFECT PLACE PDF Philip Ridley | 448 pages | 27 Feb 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408142318 | English | London, United Kingdom Philip Ridley | Knight Hall Agency Qty :. This volume contains Ridley's first three plays, which heralded the arrival of a unique and disturbing voice in the world of contemporary drama. They are seminal works in the development of the 'in yer face' theatre that emerged in Britain during the mids. The three plays here all manifest Ridley's vivid and visionary imagination and the dark beauty of his outlook. They resonate with his trademark themes: East London, Ridley Plays 1: The Pitchfork Disney; the Fastest Clock in the Universe; Ghost from a Perfect Place, moments of shocking violence, memories of the past, fantastical monologues, and that strange mix of the barbaric and the beautiful he has made all his own. The Pitchfork Disney was Ridley's first play and is now seen as launching a new generation of playwrights who were unafraid to shock and court controversy. This unsettling, dreamlike piece has surreal undertones and thematically explores fear, dreams and story-telling. The Fastest Clock in the Universe is a multi-award-winning play which caused a sensation when it premiered at Hampstead Theatre in An edgy and provocative drama, it is now regarded as a contemporary classic. Ghost from a Perfect Place is a scorchingly nasty blend of comedy, spectacle and terror where a monster from the past meets the monsters of the present. The volume contains the definitive version of the plays, plus an extended and updated introduction and three monologues B loodshot, Angry and Vooshpublished here for the first time. -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

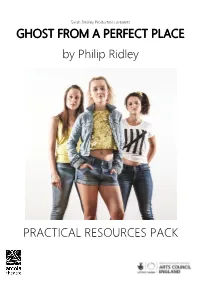

GHOST from a PERFECT PLACE by Philip Ridley PRACTICAL

Sarah Stribley Productions presents GHOST FROM A PERFECT PLACE by Philip Ridley PRACTICAL RESOURCES PACK Welcome to the Ghost From A Perfect Place resource pack. Back in the swinging sixties, Travis led a gang that terrorised East London. Now, after an absence of many years, he returns to find his old turf in the clutches of a new kind of gang…with a new kind of leader. Rio - ruler of a mob of girls - instantly captivates Travis with her haunting beauty. But soon a shocking story begins to emerge - one that shatters both their distorted memories. Ghost From A Perfect Place had its explosive premiere at Hampstead Theatre in 1994 where it was denounced as “pornographic” by The Guardian‟s Michael Billington and hailed as “a masterpiece” by The Spectator. Twenty years later it has its first major revival in this production at London‟s Arcola Theatre. The information and resources in this pack have been collated with the aim of providing an insight into the staging of the production and a practical basis for groups to further explore the Introduction themes of the play together. Please do get in touch if you would like to receive a copy of the playtext, provide feedback or to request and further information or resources. Email us at: [email protected] Enjoy! Contents The Production …………………………………………… 3 The Writer …………………………………………………… 3 Plot Summary …………………………………………….. 4 The Characters …………………………………………… 7 Interview with the Assistant Director ………… 8 Staging the Play ………………………………………… 12 Practical Resources………………………………….... 14 Community Partners …………………………………. 25 Thanks & Further Reading ………………………… 27 2 | P a g e Ghost From A Perfect Place by Philip Ridley opened at the Arcola Theatre on 11 September 2014. -

Reproducing Masculinities: Theatre and the ‘Crisis’ of the Adolescent

Reproducing Masculinities: Theatre and The ‘Crisis’ of the Adolescent Martin Heaney Royal Holloway, University of London Doctor of Philosophy: Drama and Theatre Declaration The work presented in this thesis is my own. Martin Heaney 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationships between theatre and ideas of male adolescence. It examines the historical influences and political ideologies that have shaped contemporary understandings of male adolescence and ways in which dramatists have represented them. This investigation will illuminate the function of theatre as a site where the processes of acquiring social and symbolical masculine identities are debated and interrogated. The context for this discussion is generated by the English Riots of 2011 and related social issues such as youth unemployment and perceptions of urban male ‘delinquency’ and intergenerational ‘crisis’. It is shaped by an historic perspective that illuminates continuities between these contemporary phenomena and representations of adolescent ‘crisis’ of the Edwardian period. The research undertaken is interdisciplinary. It draws on cultural materialist ideas of drama and theatre as sites where identities are contested and new constructions of age and gender are formed. It includes a discussion of the social geographies of young men from the 1900s onwards in spaces of labour, the home, the street and the theatre. This study also contextualises adolescence in relation to theories of masculinity and social histories of male experience developed in the twentieth century. It explores the different cultural and political influences that were directed towards the control of the male adolescent ‘body’ and the representation of young men by twentieth-century dramatists who advanced new ideas of masculine identity and sexuality. -

Philip Ridley'in “Kürklü Merkür”

T.C. BAHÇEŞEHİR ÜNİVERSİTESİ PHILIP RIDLEY’İN “KÜRKLÜ MERKÜR” ADLI OYUNUNUN DRAMATURJİK OLARAK İNCELENMESİ ve “DARREN” KARAKTERİNİN ANALİZİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi RIZA KOCAOĞLU İSTANBUL, 2010 i T.C. BAHÇEŞEHİR ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İLERİ OYUNCULUK PROGRAMI PHILIP RIDLEY’İN “KÜRKLÜ MERKÜR” ADLI OYUNUNUN DRAMATURJİK OLARAK İNCELENMESİ ve “DARREN” KARAKTERİNİN ANALİZİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi RIZA KOCAOĞLU Tez Danışmanı: ÖĞR. GÖR. ZURAB SIKHARULIDZE İSTANBUL, 2010 i T.C. BAHÇEŞEHİR ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İLERİ OYUNCULUK PROGRAMI Tezin Adı: Philip Ridley’in “Kürklü Merkür” Adlı Oyununun Dramaturjik Olarak İncelenmesi ve “Darren” Karakterinin Analizi Öğrencinin Adı Soyadı: Rıza Kocaoğlu Tez Savunma Tarihi: Bu tezin Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak gerekli şartları yerine getirmiş olduğu Enstitümüz tarafından onaylanmıştır. Prof. Dr. Selime SEZGİN Enstitü Müdürü Bu tezin Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak gerekli şartları yerine getirmiş olduğunu onaylarım. Öğr. Gör. Zurab SIKHARULIDZE Program Koordinatörü Bu Tez tarafımızca okunmuş, nitelik ve içerik açısından bir Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak yeterli görülmüş ve kabul edilmiştir. Jüri Üyeleri İmzalar Öğr. Gör. Zurab SIKHARULIDZE ------------------ Doç. Dr. Melih Zafer ARICAN ------------------ Öğr. Gör. Tamar KHORAVA ------------------- ÖZET PHILIP RIDLEY’İN “KÜRKLÜ MERKÜR” ADLI OYUNUNUN DRAMATURJİK OLARAK İNCELENMESİ ve “DARREN” KARAKTERİNİN ANALİZİ Kocaoğlu, Rıza İleri Oyunculuk Programı Tez Danışmanı: Öğr. Gör. Zurab Sıkharulidze Şubat 2010, 40 Sayfa İngiliz genç yazarlarından Philip Ridley 1990’larda başlayan “in-yer-face” tiyatrosu hareketi yazarlarındandır. Bu hareket başlangıcından gelişimine incelenmiştir. Sonra yazarın yaşamı ve sanat anlayışı, ürünleri belirtilmiştir. Yazarın Kürklü Merkür oyunu, zaman, mekan algısı içinde, olaylar zincirine bağlı olarak, anlam birimleri, metaforları ile incelenmiştir. Bu inceleme ışığında oyunun başkişilerinden “Darren” karakterinin analizi yapılmıştır. Anahtar kelimeler: İn-yer-face, Kürklü Merkür, Philip Ridley.