Discounting Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dominance and Monopolies Review, Fifth Edition

Dominance and Monopolies Review Fifth Edition Editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn lawreviews the Dominance and Monopolies Review The Dominance and Monopolies Review Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Dominance and Monopolies Review, - Edition 5 (published in July 2017 – editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn) For further information please email [email protected] Dominance and Monopolies Review Fifth Edition Editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn lawreviews PUBLISHER Gideon Roberton SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGERS Thomas Lee, Joel Woods ACCOUNT MANAGERS Pere Aspinall, Sophie Emberson, Laura Lynas, Jack Bagnall MARKETING AND READERSHIP COORDINATOR Rebecca Mogridge RESEARCHER Arthur Hunter EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Gavin Jordan HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Martin Roach SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Paul Howarth Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2017 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained -

Reports of Cases

Report s of C ases JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Fourth Chamber) 11 December 2013 * (Competition — Concentrations — European markets for internet communications services — Decision declaring the concentration compatible with the internal market — Manifest errors of assessment — Obligation to state reasons) In Case T-79/12, Cisco Systems Inc., established in San Jose, California (United States), and Messagenet SpA, established in Milan (Italy), represented by L. Ortiz Blanco, J. Buendía Sierra, A. Lamadrid de Pablo and K. Jörgens, lawyers, applicants, v European Commission, represented by N. Khan, S. Noë and C. Hödlmayr, acting as Agents, defendant, supported by Microsoft Corp., established in Seattle, Washington (United States), represented by G. Berrisch, lawyer, intervener, APPLICATION for annulment of Commission Decision C(2011) 7279 of 7 October 2011, declaring the concentration between undertakings involving the acquisition of Skype Global Sàrl by Microsoft Corporation (Case COMP/M.6281 – Microsoft/Skype) to be compatible with the internal market and the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA), THE GENERAL COURT (Fourth Chamber), composed of S. Papasavvas, acting as President, M. van der Woude (Rapporteur) and C. Wetter, Judges, Registrar: S. Spyropoulos, Administrator, * Language of the case: English. EN ECLI:EU:T:2013:635 1 JUDGMENTOF 11. 12. 2013 – CASE T-79/12 CISCO SYSTEMSAND MESSAGENET v COMMISSION having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearing on 29 May 2013, gives the following Judgment Facts Parties to the proceedings 1 The applicants, Cisco Systems Inc. (‘Cisco’) and Messagenet SpA (‘the applicants’), are undertakings that provide, inter alia, internet-based communications services and software for, respectively, undertakings and the general public. -

Messagenet Services Contract

MESSAGING AND TELECOMMUNICATION SERVICES ART. 1 – OBJECT OF AGREEMENT 1.1 The object of the present agreement is the MESSAGENET s.r.l.supply of various messaging and telecommunication services, including sending and receving faxes through e-mail, sending and receiving SMS, ip phonics and voicemail and hybrid mail services. MESSAGENET s.r.l. has its registered office in Via Mario Pagano 47, Milan, Italy, company register 1605496, VAT no. 13004930155, and hereafter referred to as “MESSAGENET”. 1.2 Services offered by MESSAGENET are subscribable individually, unless stated otherwise. Services have basic technical access requirements that users must view through the web before subscribing to any of them. 1.3 Before using any MESSAGENET service, subscription to www.messagenet.it is required, together with personal data and other information required by MESSAGENET. ART. 2 – DURATION OF AGREEMENT 2.1 The present agreement starts with activation of at least one service by MESSAGENET. 2.2 Free services do not expire and can be withdrawn both by the user and MESSAGENET at any time, and MESSAGENET will hold no responsibility towards the user. 2.3 Services with fixed fee run until expiration of the fee and are renewable. 2.4 Recharge services with payment expire a year after their last recharge. 2.5 The present agreement ceases when none of the client’s services are active,upon client request of cancellation through the web or a registered letter with return receipt to MESSAGENET. In case of unsubscription from any service that includes fee division into installments, to proceed with the cancellation MESSAGENET will require that the client pay all fees not paid until the expiration of any subscribed service. -

2020 Annual Campus Safety Report

2020 Annual Security Report & Annual Fire Safety Report for Valparaiso University [This Page Intentionally Left Blank] 2020 Valparaiso University Annual Security and Fire Safety Report Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................................... ii Resources at a Glance ........................................................................................................................................................... iv Safety and Security ........................................................................................................................................................... iv Campus Offices .................................................................................................................................................................. iv Title IX Contacts ................................................................................................................................................................ iv Health Resources .............................................................................................................................................................. iv Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Resources ............................................................... iv Mental Health Resources .................................................................................................................................................. -

Text Messaging at Reference: a Preliminary Survey

Text Messaging at Reference: A Preliminary Survey Steven K. Profit ABSTRACT. This article relates the results of a survey of academic libraries using text messaging as a means for delivering reference services. Information concerning the hardware, software, costs, staffing, hours of operation, service life, and patron use is presented. KEYWORDS. Text messaging. Short Message Service (SMS), text a librarian, academic libraries, reference services INTRODUCTION This article will focus on the current use of text messaging as a means for delivering reference services in academic libraries. It will present the results of a survey of some of the few institutions using text messaging in this man- ner. The survey was part of the exploration phase of learning the various ways text messaging is being employed for reference services. The terms text messaging and Short Message Service (SMS) are used interchangeably. LITERATURE REVIEW There are not many libraries using text messaging for reference services, and consequently there isn't much literature on the topic. Giles Steven K. Profit, MLIS, is Assistant Professor and Virtual Reference Services Librarian, Marlene & Nathan Addlestone Library, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC (E-mail: [email protected]). The Reference Librarian, Vol. 49(2) (#102) 2008 Available online at http://www.haworthpress.com © 2008 by The Haworth Press. All rights reserved. doi:10.1080/02763870802101328 129 130 THE REFERENCE LIBRARIAN and Grey-Smith (2005) concentrate on the subject and describe the process of implementing SMS reference service at the library at Curtin University of Technology. In her blog LibrarianlnBlack, Sarah Houghton (2005a) reports on the implementation and use of SMS at Southeastem Louisiana University. -

Proyecto Tic Ies Don Bosco

CONVOCATORIA DE PROYECTOS TIC CURSO 2005/2006 IES DON BOSCO (VALVERDE DEL CAMINO /HUELVA) ÁMBITO: INTEGRACIÓN DE LAS TIC EN LA PRÁCTICA DOCENTE ÍNDICE A) PROYECTO EDUCATIVO PARA LA INCORPORACIÓN DE LAS TIC A LA PRÁCTICA DOCENTE I JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL PROYECTO II OBJETIVOS QUE, A CORTO O LARGO PLAZO, SE PRETENDEN ALCANZAR III DESARROLLO DEL PROYECTO POR ÁREAS DE CONOCIMIENTO Y MÓDULOS CON ESPECIFICACIÓN DE: - PROPUESTA METODOLÓGICA GLOBAL - OBJETIVOS - CONTENIDOS - ACTIVIDADES - EVALUACIÓN - PROPUESTAS METODOLÓGICAS ESPECÍFICAS - INDICACIONES ESPECÍFICAS SOBRE EL TRATAMIENTO A LOS ALUMN@S CON NEE Y MEDIDAS PARA FOMENTAR LAS IGUALDADES DE CONDICIONES DE LOS DIFERENTES SEXOS - NECESIDADES DE FORMACIÓN PROYECTOS DE DEPARTAMENTOS PROYECTO DE FÍSICA Y QUÍMICA MÚSICA DIBUJO C. SOCILAES TECNOLOGÍA LENGUA CASTELLANA INGLÉS CFGM SERVICIOS SOCIALES Y A LA COMUNIDAD AUTOMOCIÓN MADERA ORIENTACIÓN MATEMÁTICAS CIENCIAS NATURALES FRANCÉS CFGS STI CLÁSICAS INFORMÁTICA IV TRATAMIENTO A LOS ALUMN@S CON NEE Y MEDIDAS PARA FOMENTAR LAS IGUALDADES DE CONDICIONES DE LOS DIFERENTES SEXOS V ORGANIZACIÓN Y DOTACIÓN DE AULAS Y ESPACIOS RELACIONADA CON EL APARTADO III VI AULAS DONDE NO SE REQUIERE EL USO DEL ORDENADOR B) PREVISIÓN DE MODIFICACIONES EN EL PCC Y EN EL PLAN ANUAL C) COMPROMISO FIRMADO DEL PROFESORADO SOBRE EL USO DE LA PLATAFORMA PASEN D) REUTILIZACIÓN DE RECURSOS EXISTENTES E) SEGUIMIENTO DEL DESARROLLO DEL PROYECTO Y PROCESO DE EVALUACIÓN F) DIAGNÓSTICO DE LAS NECESIDADES DE FORMACIÓN DEL PROFESORADO DEL CENTRO Y PLAN PREVISTO G) MEDIDAS DE DIFUSIÓN DEL PROYECTO ENTRE LOS DIFERENTES COLECTIVOS DE LA COMUNIDAD EDUCATIVA A) PROYECTO EDUCATIVO I. JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL PROYECTO El I.E.S. “Don Bosco” se encuentra en la localidad onubense de Valverde del Camino, (12.554 habitantes), un pueblo industrial, cabeza de comarca, situado geográficamente en el centro de la provincia y que está bien comunicado con la zona norte de la Sierra a través de la N- 435, con la capital, con el Andévalo, por carreteras comarcales, y con Sevilla, mediante la autovía del Quinto Centenario (A-49). -

Nokia Symbian^3 and Symbian S60 SIP Settings for Voip Calls

Nokia Symbian^3 and Symbian S60 SIP Settings f... http://vesakoret.wordpress.com/2010/11/26/nokia-e... Vesa Koret’s Blog November 26, 2010 Nokia Symbian^3 and Symbian S60 SIP Settings for VoIP calls Filed under: Mobile VoIP,nokia,Setting up VOIP / SIP on a Nokia,Setting up Voip on Nokia,SIP,symbian,Telephony,VoIP — Vesa Koret @ 11:28 am Tags: 5630 XpressMusic, ATT, C6-00, C6-01, CallCentric, configuração de VOIP, E5, E52, E61, E63, E7, E70, E71, E72, E73, E75, eutelia, fastweb, freephonie, internet phone, IP Telephony, messagenet, Mobile VoIP, mVoIP, N7, N8, N97, nettipuhelin, Nokia, Nokia sip client, Nokia VOIP, Pennytel, saunalahti, Setting up VOIP / SIP on a Nokia, SIP, SIP Configuration, sonera, Sprint, Symbian S60, Symbian^3, T-Mobile, Telecom, Telephony, Terrasip, Three Mobile, Verizon, Vodafone, Voice over IP, VoIP, voip.ms, Vono, Voxalot, Voz IP To use a VoIP system, we’ll need three things: A high-speed internet connection, a VoIP service plan, and phone equipment. Today we walk through the 3rd requisite, phone equipment. More precisely mobile phone equipment, Nokia Symbian^3 and Symbian S60 devices and how to make them work things out with some VoIP service plans. Can you relate to any of these thoughts: I have a VoIP enabled Smartphone and would like to lower my phone bills. I would like to get rid of the ridiculous landline charges without losing my home or small business number. I make expensive long-distance or international calls and would like to cut those costs. I run a small business and phone bills make significant part of my overhead. -

Competition Policy Digital Age

COMPETITION POLICY DIGITAL AGE A Practical Handbook About this Handbook This Handbook is for you if you have an interest in competition policy in the digital communications sector and, in particular, if you are: • A lawmaker, or in the policy departments of regulators and competition authorities recognising a need to reconsider the current system, in a way that takes into account: - the interplay between telecoms regulation and the enforcement of competition law; - the traditional tools and categories in market definition and market assessment; and - the need to ensure that different operators providing a similar service are treated in the same way in terms of competition policy. • An enforcer of regulation, with or without concurrent competition law powers, wishing to understand how to regulate the telecoms sector in the digital age, due account being taken of what competition law enforcers can also do. • An enforcer of competition law wishing to gain a better understanding of the competitive forces that are shaping the digital age. October 2015 Copyright © 2015 GSMA PDF Navigation Instructions For optimal visualisation please download this PDF onto your device and view it in Adobe Acrobat Reader. Competition Policy in the Digital Age How Growing Digitisation Impacts Competition Policy Links and services the prime issue for consumers. 1. Communications In tandem with this, a new breed of digital are converging market places have emerged, the main purpose of which is to sell to developers and It is generally understood that the digital age producers one product, namely the attention brought about the convergence of fixed, mobile and media networks technology and that this of consumers. -

Airport Emergency Communications for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs (2019)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/25507 SHARE Airport Emergency Communications for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs (2019) DETAILS 140 pages | 8.5 x 11 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-48049-9 | DOI 10.17226/25507 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK IEM; Airport Cooperative Research Program; Transportation Research Board; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine FIND RELATED TITLES SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019. Airport Emergency Communications for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25507. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Airport Emergency Communications for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM ACRP RESEARCH REPORT 201 Airport Emergency Communications for People with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs IEM Research Triangle Park, NC Subscriber Categories Aviation • Operations and Traffic Management • Security and Emergencies Research sponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration 2019 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

OIT Progress Report 2013

2013 Progress Report SMU Office of Information Technology University Goals Throughout the report blue boxes like this highlight University goals that each project supports. Our Vision Support the academic and administrative mission of the University Our Mission Actively seek input from our customers, understand their needs and challenges, work with them to implement appropriate solutions, and create and nurture the vital information technology environment required for SMU to achieve its vision of excellence in education Table of Contents Welcome 3 Journey of OIT 4 About Us 6 Up and Coming Projects New Software Aids Faculty 8 Telephony Upgrade Planning 10 Fiber Cable Plant 10 Distributed Antenna System 11 Connect with OIT University Data Center 12 smu.edu/oit High Performance Computing 14 Technology News Sustainable Security 16 smu.edu/OIT/StayInformed/Newsletter Information Security 18 Twitter Enhanced Support 20 twitter.com/smuoit New and Expanded Services 21 Blog IT Unification 22 blog.smu.edu/itconnect 2 Welcome Welcome Front row left to right: Roxanne Crowley (Financial Officer), George Finney (Director), Karie Conklin (Assistant to the CIO), andAbby Kinney (Director) Back row left to right: Ron Lujan (Director), Joe Gargiulo (CIO), Brad Boeke (Director), Jesse Miller (Director), and Allen Hughes (Director) e have been busy working We manage hundreds of projects a We invite you to review our Progress to deliver the services that year. Without a standardized project Report to see some of the projects our students, faculty, staff, management, change management, that we have been working on and the Walumni, and visitors not only expect and incident management incredible people that get it done. -

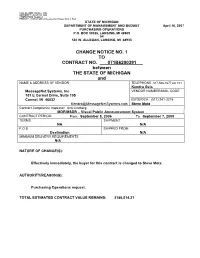

Change Notice No. 1 to Contract No. 071B6200391

Form No. DMB 234 (Rev. 1/96) AUTHORITY: Act 431 of 1984 COMPLETION: Required PENALTY: Contract will not be executed unless form is filed STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET April 16, 2007 PURCHASING OPERATIONS P.O. BOX 30026, LANSING, MI 48909 OR 530 W. ALLEGAN, LANSING, MI 48933 CHANGE NOTICE NO. 1 TO CONTRACT NO. 071B6200391 between THE STATE OF MICHIGAN and NAME & ADDRESS OF VENDOR TELEPHONE 317-566-1677 ext 101 Kendra Geis MessageNet Systems, Inc VENDOR NUMBER/MAIL CODE 101 E Carmel Drive, Suite 105 Carmel, IN 46032 BUYER/CA (517) 241-3215 [email protected] Steve Motz Contract Compliance Inspector: Ann Lindberg MDE/MSDB – Visual Public Announcement System CONTRACT PERIOD: From: September 8, 2006 To: September 7, 2009 TERMS SHIPMENT NA N/A F.O.B. SHIPPED FROM Destination N/A MINIMUM DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS N/A NATURE OF CHANGE(S): Effectively immediately, the buyer for this contract is changed to Steve Motz. AUTHORITY/REASON(S): Purchasing Operations request. TOTAL ESTIMATED CONTRACT VALUE REMAINS: $186,514.21 BPO 071B6200 Form No. DMB 234 (Rev. 1/96) AUTHORITY: Act 431 of 1984 COMPLETION: Required PENALTY: Contract will not be executed unless form is filed STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET September 8, 2006 PURCHASING OPERATIONS P.O. BOX 30026, LANSING, MI 48909 OR 530 W. ALLEGAN, LANSING, MI 48933 NOTICE OF CONTRACT NO. 071B6200391 between THE STATE OF MICHIGAN and NAME & ADDRESS OF VENDOR TELEPHONE 317-566-1677 ext 101 Kendra Geis MessageNet Systems, Inc VENDOR NUMBER/MAIL CODE 101 E Carmel Drive, Suite 105 Carmel, IN 46032 BUYER/CA (517) 241-2005 [email protected] Lisa Morrison Contract Compliance Inspector: Ann Lindberg MDE/MSDB – Visual Public Announcement System CONTRACT PERIOD: From: September 8, 2006 To: September 7, 2009 TERMS SHIPMENT NA N/A F.O.B. -

A Digital Manifesto.Indd

A Digital Manifesto_ An open and safe Internet experience for all v About Telefónica_ Mexico Revenue 1,742.5 M €* Investment 427 M €* Accesses 20,326.9** Clients 20,622.1** Central America Venezuela Revenue 677.6 M €* Revenue 3,388.5 M €* Investment 130.8 M €* Investment 463 M €* Accesses 9,714** Accesses 11,664.6** Clients 10,987.2** Clients 11,861.3** Colombia Revenue 1,778.6 M €* Investment 352 M €* Accesses 14,126.1** Brazil Clients 14,250.9** Revenue 14,303.5 M €* Investment 2,444 M €* Ecuador Accesses 91,369.8 ** Clients 91,927.6** Revenue 473.4 M €* Investment 85 M €* Accesses 5,019.6** Clients 5,096.1** Peru Revenue 2,470 M €* Investment 378 M €* Accesses 20,299.9** Clients 20,897.2** Chile Uruguay Revenue 2,576.9 M €* Revenue 254.8 M €* Investment 606 M €* Investment 28 M €* Accesses 13,147** Accesses 1,843.5** Clients 13,452.2** Clients 1,845.9** Argentina Revenue 3,912 M €* Investment 519 M €* Accesses 24,136** Clients 26,999.4** Present in 24 countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Germany, Guatemala, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, Slovakia, Spain, UK, Uruguay, USA and Venezuela. 62,356 M €* 9,458 M €* 133,263 joint revenues total investment employees 95% of all contracts are permanent * Data in million euros for Fiscal Year 2012 / ** Data in thousands as of June 2013 v We believe that the possibilities of technology should be open to everyone United Kingdom Revenue 7,235.1 M €* Germany Investment 748 M €* Accesses 23,842.2** Revenue 5,514.9 M €* Clients 23,680.2** Investment 609 M €* Accesses 25,372.8** Clients 25,436.6** Ireland Czech Republic Revenue 629 M €* Revenue 1,787.8 M €* Investment 192 M €* Investment 248 M €* Accesses 1,572.7** Accesses 7,900.1** Clients 1,559.1** Clients 7,797.2** Slovakia Revenue 188.6 M €* Investment 19.6 M €* Accesses 1,354.2** Clients 1,471.4** Spain Revenue 15,173.3 M €* Investment 1,692 M €* Accesses 43,140.3** Clients 41,963.3** And_ Telefónica reinforces its global scale with alliances and collaboration agreements.