James A. Perkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOLUME 9 NOVEMBER 1, 1963 NUMBER 21 A Safe Fence Around Mount Sinai by Moses Bailey @oR u ligion b'gins with life, not with theory or report. The life is mightier than the The Inner Bidding-Norway, 1963 book that reports it. The most important thing in the world by Douglas V. Steere is to get our faith out of a book and out of a creed into living experience an d deed of life. T hat is exactly what Jesus Alone-with-ness did in the synagogue when he read the program of the L ord's by Henry B. Williams servant. H e translated ancient words into life. -RuFus M . JoNES Letter from Germany by Anni Sabine Halle Beyond and Within: Supplement of the Religious THIRTY CENTS Education Committee, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting $5.00 A YEAR 458 FRIENDS JOURNAL November 1, 1963 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE In the Field of Human Relations D I CHARD FORMAN, a member of Haverford (Pa.) .1\.. Meeting, is serving for two years as a volunteer in the VISA program of the American Friends Service Com mittee in Central America. His special assignment is in Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each Honduras, where he is a teacher in an agricultural school. month at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 19102, Penn sylvama1 (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. Richard's problem has been how to use the lectures and CARL F. WISE laboratories in zoology and the periods in the English Acting Edltor language in such a way as to make a special contribution ETHAN A. -

Cornell University Financial Report 2006-2007

1 The Cornell universi The Cornell A Message from the President T y r epor T 2006–07 Dear Cornellians and Friends of the University, he year that ended June 30, 2007, was one of significant achievement for Cornell: a near-record number of Cornell faculty members elected to distin- guished national academies; the largest number of applications ever received for places in the first-year class; an impressive number of Rhodes, Marshall, T Luce, Goldwater, Udall, and other national and international scholarships earned by our students and recent alumni; national recognitions of our efforts to be an employer of choice; the successful launch of one of the largest university-wide fund- raising campaigns in the history of American higher education; and the best year in fund-raising in the history of Cornell. This report documents some of the ways in which Cornell has demonstrated national and international leadership this year while also advancing the priorities that will enable it to continue to attract, inspire, and support the world’s best faculty, staff, and students over the longer term. David J. Skorton President Cornell University David Skorton named president • Cornell welcomes student refugees from Hurricane Katrina • Hunter Rawlings signs education agreement in China • Rawlings addresses intelligent design head-on • students take outreach to developing world • faculty take lead on strategic planning initiatives and on sustainability • faculty members win national recognition 2 2006–07 T epor r y T niversi u he Cornell he Cornell T David Skorton named president • Cornell welcomes student refugees from Hurricane Katrina • Hunter Rawlings signs education agreement in China • Rawlings addresses intelligent design head-on • students take outreach to developing world • faculty take lead on strategic planning initiatives and on sustainability • faculty members win national recognition 3 The Cornell universi The Cornell Major Themes of the Year T y r epor T 2006–07 David J. -

The Summer Clouds Had Rumbled Through the Valley All

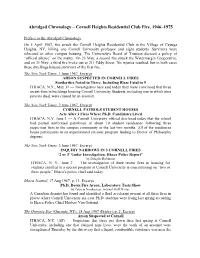

Abridged Chronology – Cornell Heights Residential Club Fire, 1946–1975 Preface to the Abridged Chronology On 5 April 1967, fire struck the Cornell Heights Residential Club in the Village of Cayuga Heights, NY, killing one Cornell University professor and eight students. Survivors were relocated to other campus housing. The University's Board of Trustees decreed a policy of “official silence” on the matter. On 23 May, a second fire struck the Watermargin Cooperative, and on 31 May, a third fire broke out at 211 Eddy Street. No injuries resulted, but in both cases these dwellings housed survivors of the first fire. The New York Times, 1 June 1967, Excerpt ARSON SUSPECTED IN CORNELL FIRES Similarities Noted in Three, Including Blaze Fatal to 9 ITHACA, N.Y., May 31 ⸺ Investigators here said today they were convinced that three recent fires in buildings housing Cornell University Students, including one in which nine persons died, were caused by an arsonist. The New York Times, 2 June 1967, Excerpt CORNELL PATROLS STUDENT HOUSES Acts After 3 Fires Where Ph.D. Candidates Lived ITHACA, N.Y. June 1 ⸺ A Cornell University official disclosed today that the school had posted uniformed patrolmen at about 10 student residences following three suspicious fires in the campus community in the last two months. All of the residences house participants in an experimental six-year program leading to Doctor of Philosophy degrees. The New York Times, 3 June 1967, Excerpt INQUIRY NARROWS IN 3 CORNELL FIRES ‘2 or 3’ Under Investigation, Ithaca Police Report” by Douglas Robinson ITHACA, N. Y., June 2 — The investigation of three recent fires in housing for students enrolled in a special program at Cornell University is concentrating on “two or three people,” Ithaca’s police chief said today. -

The Aims of Overseas Study for US Higher Education in the Twentieth

Rhetoric and Reality in Study Abroad: The Aims of Overseas Study for U.S. Higher Education in the Twentieth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Contreras Jr., Eduardo. 2015. Rhetoric and Reality in Study Abroad: The Aims of Overseas Study for U.S. Higher Education in the Twentieth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:16461042 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rhetoric and Reality in Study Abroad: The Aims of Overseas Study for U.S. Higher Education in the Twentieth Century Eduardo Contreras Jr. Julie Reuben Jal Mehta David Engerman A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Education of Harvard University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education 2015 © 2015 Eduardo Contreras Jr. All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout the process of writing this dissertation I have been fortunate to have a large group of intellectual and professional mentors, supportive friends, and loving family members to help me along the way. It gives me great joy to thank them here. First and foremost, I want to thank my terrific advisor, Julie Reuben and the members of my dissertation committee, Jal Mehta and David Engerman for their sage advice, thoughtful feedback, and continued support. -

Report of the Centennial Year of the University of Illinois

LI E) R.AFIY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS C I' ll ., II io- Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from CARLI: Consortium of Academic and Researcii Libraries in Illinois http://www.archive.org/details/reportofcentenni1968univ FROM A DISTINGUISHED PAST - A PROMISING FUTURE of the Centennial Year of The University of Illinois FEBRUARY 28, 1967 TO MARCH 11, 1968 - 232 Davenport House 807 South Wright Street Champaign, Illinois April 14, 1969 TO THE PERSON ADDRESSED, I enclose with this the report of the Centennial Year at the University of Illinois. I hope you will find it a useful reference book for the events of the year. Sincerely, \ FHT-Y Fred H. Turner Enclosure REPORT OF THE CENTENNIAL YEAR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS REPORT OF THE CENTENNIAL YEAR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS FEBRUARY 28 , 1967 to MARCH H, 1968 The report of the Centennial Year of the University of Illinois consists of two sections - a brief statement concerning each part, event, or activity of the Centennial Year, and extended appendices for related sections giving details on each category. The Centennial Office has assembled copies of all publi- cations, programs, posters, and other printed materials related to these events. In addition. Miss Hazel Yates and Mrs. Rose Holmes of the Centennial Office staff, have prepared thirty-five books of clippings in permanent form which have been indexed for ready use. These books provide the most rapid source of reference to all Cen- tennial events and will be placed in a designated depository when the Centennial Office is closed. -

Medical College 1963-1964 Cornell University Announcements

CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS AUGUST 21, 1963 MEDICAL COLLEGE 1963-1964 CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS The Cornell Announcements are designed to give prospective stu dents and others information about the University. The prospective student should have a copy of General Information; after consulting that, he may wish to write for one or more of the following Announcements: New York State College of Agriculture (Four-Year Course), New York State College of Agriculture (Two-Year Course), College of Architecture, College of Arts and Sciences, School of Education, Department of Asian Studies, New York State College of Home Economics, School of Hotel Administration, New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Military Training, Summer School. Announcements of the College of Engineering may also be obtained. Please specify if the information is for a prospective student. Undergraduate preparation in a recognized college or university is required for admission to the following Cornell divisions, for which Announcements are available: Graduate School of Business and Public Administration, Law School, Medical College, Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing, Graduate School of Nutrition, New York State Veterinary College, Graduate School. Requests for these publications may be addressed to CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS ! EDMUND EZRA DAY HALL, ITHACA, NEW YORK • ♦ CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS. Volume 55. Number 4. August 21, 1963. Published twenty-one times a year: twice in March, April, May, June, July, August, October, and December; three times in Septem ber; once in January and in November; no issues in February. Published by Cornell University at Edmund Ezra Day Hall, 18 East Avenue, Ithaca, New York. Second-class postage paid at Ithaca, New York. -

NEW YORK STATE VETERINARY COLLEGE K * V Ji|

NEW YORK STATE VETERINARY COLLEGE K * v ji| . ir: ■ ■... :4x A ' m m m - ■ C o r n e l l U n iv e r sit y I g t - ' S I t h a c a , N e w Y o r k J ! i l l ! . ■■■■ “ And let those learn, who here shall meet, True wisdom is with reverence crowned, f l llll, And science walks with humble feet Lw|I~ ~~J] ~ m To seek the God that faith hath found.” Caleb Thomas Winchester Winter Evening Andrew Dickson White Goldwin Smith Hall C h r is t m a s , 1963 D ear C o r n e l l ia n : James Wills Lenhart, Pastor of the Plymouth Congregational Church, Des Moines, Iowa, has said that “ It is one thing to be ready for Christmas. It is another thing to be prepared for it.” And he wonders if it is not true that perhaps “ the very getting ready gets in the way of being prepared.” Preparing for Christmas is quite the opposite of getting ready. “ It gets rid of the things that get piled up; unloosing ourselves of packages— the heavy packages we have carried all year long, the packages of our conceits, our pride, our shrewdness, our hard- headedness, and that wisdom which really is not wise.” “ You see, in preparing for Christmas as in any other worthwhile endeavor, perfection takes place not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to take away.” Surely it is more important to experience the mystery of Christmas than to get ready for the holiday season; the mystery of a reawakening of our understanding of the meaning of the incarnation, the mystery of the feelings and spontaneity, thanksgiving, warmth and vivacity when the word “ Christmas” opens the floodgates of memory.