The Aims of Overseas Study for US Higher Education in the Twentieth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 29, 2010 Draft History of Education Society 50 Annual

September 29, 2010 Draft History of Education Society 50th Annual Meeting November 4-7, 2010 LeMeridien Hotel Cambridge, Massachusetts THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 1:00 to 2:30 p.m. I. BUILDING A NATION THROUGH EDUCATION Gail Wolfe (Washington University in St. Louis), chair. Eileen Tamura (University of Hawai’i), discussant. Theodore Christou (University of New Brunswick), “ Progressive Education for a Progressive Canadian Society: Ontario’s Progressivist Rhetoric Post-WWI.” M. Carolina Zumaglini (Florida International University), “‘Don yo’ and the Manns: U.S.-Argentine Public Educational Systems, 1847 – 1888.” Marina Moura (Univ. Presbiteriana Mackenzie), “Children, Education and The Pro-Childhood Crusade.” Natalia Mehlman Petrzela (New School University), “Constructing Family Values: Parents, Teachers, Taxes and Sex Education in Contemporary America.” 1:00 to 2:30 p.m. II. AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR EQUALITY Louis Ray (Fairleigh Dickinson University), discussant. Shannon Mokoro (Salem State College), “Racial Uplift and Self-Determination: The African Methodist Episcopal Church and Its Pursuit of Higher Education.” Kabria Baumgartner (University of Massachusetts), “The Educational Thought of Susan Paul: A Short Intellectual History.” Vincent Willis (Emory University), “Refusing to Accept Unequal Education: Black Children in the Aftermath of the Brown Decision, 1954-1972.” 1:00 to 2:30 p.m. III. PANEL: “UNEARTHING THE ‘80S: A DECADE OF CRISIS AND CHANGE.” Heather Lewis (Pratt Institute), “The Effective Schools Movement and the Pursuit of Excellence in the 1980s.” Emily Straus (State University of New York at Fredonia), “Teachers at Risk: A Decade of Struggle for Teachers in the Compton Unified School District.” Bethany L. Rogers (The College of Staten Island, CUNY), “Teaching, Youth, and the Paradox of the Late 1980s.” THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 (CONT.) 1:00 to 2:30 p.m. -

Modern Universities, Absent Citizenship? Historical Perspectives

Modern Universities, Absent Citizenship? Historical Perspectives William Talcott Visiting Scholar, University of Maryland [email protected] CIRCLE WORKING PAPER 39 SEPTEMBER 2005 CIRCLE Working Paper 39: September 2005 Modern Universities, Absent Citizenship? Historical Perspectives CIRCLE Working Paper 39: September 2005 Modern Universities, Absent Citizenship? Historical Perspectives The historical study of university campuses and character-building might be described, as they can tell us much about the changing character were by a Berkeley student in 1892, as “elective and presuppositions of citizenship. Likewise, the studies.”3 study of citizenship can shed considerable light on Several developments stand out in the the nature of universities. Throughout American formation of the university model. Following Johns history, various elite institutions can be seen Hopkins’ lead, institutions emphasizing research struggling to establish a semblance of order and and science came increasingly to dominate higher control in political society—most clearly in the late education in the post Civil War U.S. Charles 19th century with large numbers of immigrants Elliot’s elective system instituted at Harvard freed changing the urban landscape, and with populist undergraduates to pursue their own interests rather movements threatening elite cultural and political than following a course set by the institution. Land dominance, but equally in the face of early 20th grant universities emphasized practical training century phenomena of mass society, propaganda, for farmers, mechanics, miners, engineers, as well and global interdependence.1 I find it helpful to as primary and secondary school teachers. New, think of modern universities, emerging in the more private and scientific notions of citizenship late 19th century, as right there in the struggle, were gradually eclipsing the collegiate emphasis as new institutional arenas of public practice to on moral character. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOLUME 9 NOVEMBER 1, 1963 NUMBER 21 A Safe Fence Around Mount Sinai by Moses Bailey @oR u ligion b'gins with life, not with theory or report. The life is mightier than the The Inner Bidding-Norway, 1963 book that reports it. The most important thing in the world by Douglas V. Steere is to get our faith out of a book and out of a creed into living experience an d deed of life. T hat is exactly what Jesus Alone-with-ness did in the synagogue when he read the program of the L ord's by Henry B. Williams servant. H e translated ancient words into life. -RuFus M . JoNES Letter from Germany by Anni Sabine Halle Beyond and Within: Supplement of the Religious THIRTY CENTS Education Committee, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting $5.00 A YEAR 458 FRIENDS JOURNAL November 1, 1963 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE In the Field of Human Relations D I CHARD FORMAN, a member of Haverford (Pa.) .1\.. Meeting, is serving for two years as a volunteer in the VISA program of the American Friends Service Com mittee in Central America. His special assignment is in Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each Honduras, where he is a teacher in an agricultural school. month at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 19102, Penn sylvama1 (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. Richard's problem has been how to use the lectures and CARL F. WISE laboratories in zoology and the periods in the English Acting Edltor language in such a way as to make a special contribution ETHAN A. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. Woodrow Wilson, “The Significance of the Student Movement to the Nation,” in APJRM, 168. 2. Francis Patton, “The Significance of the Student Movement to the Church,” Int 25, no. 4 (January 1903): 81. 3. For example, see Lawrence R. Veysey, The Emergence of the American University (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965); Frederick Rudolph, The American College and University (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1962); John Brubacher and Willis Rudy, Higher Education in Transition: A History of American Colleges and Universities, 4th ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1958); Helen Horowitz, Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures from the End of the Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); and Harry E. Smith, Secularization and the University (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1968). 4. See, for example, Veysey, The Emergence of the American University; Rudolph, The American College and University. 5. See George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Julie Reuben, The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Jon H. Roberts and James Turner, The Sacred and the Secular University (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). 6. From Marsden’s perspective, liberal Protestantism eased the transition from the seemingly innocent methodological perspective to the more insidious ideologi- cal variety that prevented religious themes from entering the university “market- place of ideas.” Julie Reuben, while not discounting Marsden’s argument, does complicate his perspective by looking more specifically at how religion was conceived in relation to the search for truth at major universities in this era. -

Cornell University Financial Report 2006-2007

1 The Cornell universi The Cornell A Message from the President T y r epor T 2006–07 Dear Cornellians and Friends of the University, he year that ended June 30, 2007, was one of significant achievement for Cornell: a near-record number of Cornell faculty members elected to distin- guished national academies; the largest number of applications ever received for places in the first-year class; an impressive number of Rhodes, Marshall, T Luce, Goldwater, Udall, and other national and international scholarships earned by our students and recent alumni; national recognitions of our efforts to be an employer of choice; the successful launch of one of the largest university-wide fund- raising campaigns in the history of American higher education; and the best year in fund-raising in the history of Cornell. This report documents some of the ways in which Cornell has demonstrated national and international leadership this year while also advancing the priorities that will enable it to continue to attract, inspire, and support the world’s best faculty, staff, and students over the longer term. David J. Skorton President Cornell University David Skorton named president • Cornell welcomes student refugees from Hurricane Katrina • Hunter Rawlings signs education agreement in China • Rawlings addresses intelligent design head-on • students take outreach to developing world • faculty take lead on strategic planning initiatives and on sustainability • faculty members win national recognition 2 2006–07 T epor r y T niversi u he Cornell he Cornell T David Skorton named president • Cornell welcomes student refugees from Hurricane Katrina • Hunter Rawlings signs education agreement in China • Rawlings addresses intelligent design head-on • students take outreach to developing world • faculty take lead on strategic planning initiatives and on sustainability • faculty members win national recognition 3 The Cornell universi The Cornell Major Themes of the Year T y r epor T 2006–07 David J. -

Jewett CV 3-21

Andrew Jewett 657 Salem End Rd. [email protected] Framingham, MA 01702 (617) 852-6229 Education University of California, Berkeley Ph.D. in History, 2002 M.A. in History, 1998 B.A. in History, 1992 Academic positions Boston College Visiting Associate Professor of History, 2017-2020 Harvard University Associate, Department of History, 2018- Associate, Department of History of Science, 2015-2019 Visiting Associate Professor of Education, 2017-2018 Associate Professor of History and of Social Studies, 2012-2017 Assistant Professor of History and of Social Studies, 2007-2012 New York University Assistant Professor/Faculty Fellow in Science Studies, John W. Draper Interdisciplinary Master’s Program in Humanities and Social Thought, 2006-2007 Vanderbilt University Lecturer, Department of History, Spring 2005 Yale University Lecturer, Department of History, 2003-2004 Fellowships and honors Martha Daniel Newell Visiting Scholar, Georgia College & State University, Spring 2021 John G. Medlin, Jr. Fellow, National Humanities Center, 2013-2014 Distinguished Guest Fellow, Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, Spring 2014 (Declined) Associate Scholar, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 2009-2010 External Faculty Fellow, Stanford Humanities Center, 2009-2010 (Declined) Associate Fellow, Center for Historical Analysis, Rutgers University, 2006-2007 (Theme: “The Question of the West”) Faculty Fellow, Center for Ethics and Public Affairs, Tulane University, 2006-2007 (Declined) Fellow, Cornell Society for the Humanities, 2005-2006 (Theme: “Culture -

The Summer Clouds Had Rumbled Through the Valley All

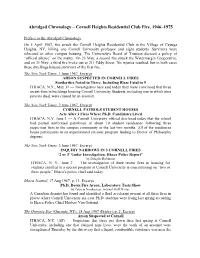

Abridged Chronology – Cornell Heights Residential Club Fire, 1946–1975 Preface to the Abridged Chronology On 5 April 1967, fire struck the Cornell Heights Residential Club in the Village of Cayuga Heights, NY, killing one Cornell University professor and eight students. Survivors were relocated to other campus housing. The University's Board of Trustees decreed a policy of “official silence” on the matter. On 23 May, a second fire struck the Watermargin Cooperative, and on 31 May, a third fire broke out at 211 Eddy Street. No injuries resulted, but in both cases these dwellings housed survivors of the first fire. The New York Times, 1 June 1967, Excerpt ARSON SUSPECTED IN CORNELL FIRES Similarities Noted in Three, Including Blaze Fatal to 9 ITHACA, N.Y., May 31 ⸺ Investigators here said today they were convinced that three recent fires in buildings housing Cornell University Students, including one in which nine persons died, were caused by an arsonist. The New York Times, 2 June 1967, Excerpt CORNELL PATROLS STUDENT HOUSES Acts After 3 Fires Where Ph.D. Candidates Lived ITHACA, N.Y. June 1 ⸺ A Cornell University official disclosed today that the school had posted uniformed patrolmen at about 10 student residences following three suspicious fires in the campus community in the last two months. All of the residences house participants in an experimental six-year program leading to Doctor of Philosophy degrees. The New York Times, 3 June 1967, Excerpt INQUIRY NARROWS IN 3 CORNELL FIRES ‘2 or 3’ Under Investigation, Ithaca Police Report” by Douglas Robinson ITHACA, N. Y., June 2 — The investigation of three recent fires in housing for students enrolled in a special program at Cornell University is concentrating on “two or three people,” Ithaca’s police chief said today. -

1 A412 Julie Reuben Fall 2015 Gutman 421 T/Th

A412 Julie Reuben Fall 2015 Gutman 421 T/Th 8:30-10:00 617-496-4918 OH: Wednesdays 2:00-5:00 [email protected] (sign up at 6TUhttp://reuben-office-hours.wikispaces.com/U6T) TFs: Bryan McAllister-Grande [email protected] 5TBrent Maher [email protected] Rachel Freeman [email protected] The History of American Higher Education This course examines the development of American higher education from the colonial period to the present. It focuses on several key questions: How have the purposes of higher education been defined and redefined over time? Why are there so many different types of colleges and universities in the United States? What have students learned while in college? Why has that been valued? Who attended college? Who was excluded and why? What were students’ experiences outside of the classroom? How did those experiences vary? In addition to gaining understanding of the history of colleges and universities, this course will give students a broader perspective on contemporary practices and problems in higher education and will help them further develop their analytic reading and writing skills. Course Requirements: UReadings Readings are available in one of three formats: online as part of the Library’s electronic resource, in an iPac, or in books. The following books are available for purchase at the Harvard Coop and are on reserve at Gutman Library: Steven Brint and Jerome Karabel, The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in American, 1900-1985; Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s Charlayne Hunter-Gault, In My Place; Christopher J. -

Higginson-Dissertation-2020

Accessible Yet Unequal: A Qualitative Study of Social Class, Race, and First-Year Experiences at a Regional Comprehensive University The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Higginson, Reid Pitney. 2020. Accessible Yet Unequal: A Qualitative Study of Social Class, Race, and First-Year Experiences at a Regional Comprehensive University. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365899 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Accessible Yet Unequal: A Qualitative Study of Social Class, Race, and First-Year Experiences at a Regional Comprehensive University A Dissertation presented by Reid Pitney Higginson to The Committee on Higher Degrees in Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Education Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2020 © 2020 Reid Pitney Higginson All Rights Reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Julie A. Reuben Reid Pitney Higginson Accessible Yet Unequal: A Qualitative Study of Social Class, Race, and First-Year Experiences at a Regional Comprehensive University Abstract Completing college is associated with tremendous benefits in American society (Carnevale et al., 2015). Yet, while college access has expanded dramatically over the past half- century, graduation rates remain frustratingly unequal by class, race, and parental education (Cahalan et al., 2019). -

American Intellectual History

Professor: Angus Burgin ([email protected]) Office Hours: https://calendly.com/burgin/office-hours AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY Overview: This graduate seminar explores historical works on ideas in an American context since the late nineteenth century, with an emphasis on recent developments in the field. Assignments and grading: This is a readings seminar, and the primary expectation is that every student will arrive in class prepared to contribute to an in-depth discussion of the assigned texts. (The “supplementary readings” are not mandatory, but are listed as a guide to help students identify further readings on specific topics.) Unless students request otherwise, this course will be graded on a pass/fail basis. Texts: Most of the readings from the course (denoted with an * in the syllabus) will be available on electronic reserve. The other readings, listed below, can either be purchased separately or checked out on a short-term basis from Eisenhower Library reserves: • Brandon Byrd, The Black Republic: African Americans and the Fate of Haiti (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019). • Katrina Forrester, In the Shadow of Justice: Postwar Liberalism and the Remaking of Political Philosophy (Harvard University Press, 2019). • Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire : A History of the Greater United States (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). • Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space 1880–1918 (Harvard University Press, 1983). • T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920 (University of Chicago Press, 1994). Wednesday, January 27th: Methodologies of Intellectual History • *Arthur Lovejoy, “The Study of the History of Ideas,” in The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (Harper & Brothers, 1936), pp. -

Report of the Centennial Year of the University of Illinois

LI E) R.AFIY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS C I' ll ., II io- Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from CARLI: Consortium of Academic and Researcii Libraries in Illinois http://www.archive.org/details/reportofcentenni1968univ FROM A DISTINGUISHED PAST - A PROMISING FUTURE of the Centennial Year of The University of Illinois FEBRUARY 28, 1967 TO MARCH 11, 1968 - 232 Davenport House 807 South Wright Street Champaign, Illinois April 14, 1969 TO THE PERSON ADDRESSED, I enclose with this the report of the Centennial Year at the University of Illinois. I hope you will find it a useful reference book for the events of the year. Sincerely, \ FHT-Y Fred H. Turner Enclosure REPORT OF THE CENTENNIAL YEAR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS REPORT OF THE CENTENNIAL YEAR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS FEBRUARY 28 , 1967 to MARCH H, 1968 The report of the Centennial Year of the University of Illinois consists of two sections - a brief statement concerning each part, event, or activity of the Centennial Year, and extended appendices for related sections giving details on each category. The Centennial Office has assembled copies of all publi- cations, programs, posters, and other printed materials related to these events. In addition. Miss Hazel Yates and Mrs. Rose Holmes of the Centennial Office staff, have prepared thirty-five books of clippings in permanent form which have been indexed for ready use. These books provide the most rapid source of reference to all Cen- tennial events and will be placed in a designated depository when the Centennial Office is closed. -

History of Education Society 60Th Annual Meeting November 5-8, 2020 Virtual Conference

History of Education Society 60th Annual Meeting November 5-8, 2020 Virtual Conference Give More Power to the People Table of Contents Welcome Page 3 HES Statement on Inclusivity Page 4 HES Information and Officers Page 5 HEQ Staff & Editorial Board Page 6 60th Annual Meeting Information Page 7 HES Committees Page 8 Special Conference Events Page 9 Program Schedule Pages 10 – 35 Related Conferences Page 36 Program Reviewers Pages 37 – 38 Program Participants Pages 39 – 51 Follow HES on Facebook (History of Education Society) and Twitter (@HistEdUSA) Welcome to HES Welcome to the 2020 Annual Meeting of the History of Education Society (HES)! Our first virtual annual meeting! I am so excited about this year’s virtual conference, the possibilities it presents, and the ideas and research it will host. Our 2020 annual meeting occurs just days after the presidential election, and marks several key anniversaries relevant to the history of education, including the 400th anniversary of the arrival of The Mayflower; the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment that gave African American males the right to vote; the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote; the 60th anniversary of the History of Education Society, the 50th anniversaries of the Chicano Movement, the Red Power Movement, the Black Power Movement, the Gay Rights Movement, the Women’s Equal Rights Movement, and the rise of Ethnic Studies programs in higher education, the 40th anniversary of A People’s History by Howard Zinn, the 30th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and the 25th anniversary of Ayers v.