Denied from the Start: Human Rights at the Local Level in North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UN Consolidated Relief Appeal 2004

In Tribute In 2003 many United Nations, International Organisation, and Non-Governmental Organisation staff members died while helping people in several countries struck by crisis. Scores more were attacked and injured. Aid agency staff members were abducted. Some continue to be held against their will. In recognition of our colleagues’ commitment to humanitarian action and pledging to continue the work we began together We dedicate this year’s appeals to them. FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON HTTP://WWW.RELIEFWEB.INT/ UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, November 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................11 Table I. Summary of Requirements – By Appealing Organisation ........................................................12 2. YEAR IN REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................13 2.1 CHANGES IN THE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION ...........................................................................................13 2.2 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW...........................................................................................................................14 2.3 MONITORING REPORT AND -

Survey of AFSC Archives on Korea (1938-2000) Created by Elizabeth Douglas ’13 in Spring 2012

Survey of AFSC Archives on Korea (1938-2000) Created by Elizabeth Douglas ’13 in Spring 2012 The AFSC in Korea: A Brief Summary The American Friends Service Committee’s (AFSC) archival on Korea first begin in 1938 when Gilbert Bowles travelled to Japanese occupied Korea. The AFSC did not begin work in the country until 1946, when it began to provide aid to the devastated country. Through the rest of the 1940s and 1950s, the AFSC provided relief to victims of both World War II and the Korean War. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the AFSC worked to expose the human rights violations perpetrated by the South Korean government. From since the 1960s, the AFSC organized various conferences and seminars on the possibility of reunifying North and South Korea. Throughout this time, AFSC delegates visited the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; each time they toured the country, they wrote detailed reports describing their experiences and observations. The AFSC’s work continues into the 21st Century, and the archives are updated to reflect the AFSC’s current projects. How to Use this Survey: The following survey was designed to give a brief overview of the AFSC’s collection of materials on Korea. I have first listed the contents of the AFSC reference files on Korea and then the individual boxes chronologically. Within in each year is a list of relevant boxes and their pertinent contents. As the AFSC’s archives on Korea span a considerable period, there is much variance in organization systems. Although I did not list the names of every folder in every box, I gave a brief summary of relevant materials in each box; these summaries are not comprehensive but merely give an overview of the material. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

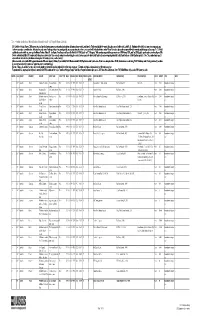

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

Book Review of "Nothing to Envy," by Barbara Demick, and "The Cleanest Race," by B.R

Book review of "Nothing to Envy," by Barbara Demick, and "The Cleanest Race," by B.R. Myers By Stephen Kotkin Sunday, February 28, 2010 NOTHING TO ENVY Ordinary Lives in North Korea By Barbara Demick Spiegel & Grau. 314 pp. $26 THE CLEANEST RACE How North Koreans See Themselves -- and Why It Matters By B.R. Myers Melville House. 200 pp. $24.95 "If you look at satellite photographs of the Far East by night, you'll see a large splotch curiously lacking in light," writes Barbara Demick on the first page of "Nothing to Envy." "This area of darkness is the Democratic People's Republic of Korea." As a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, Demick discovered that the country isn't illuminated any further by traveling there. So she decided to penetrate North Korea's closed society by interviewing the people who had gotten out, the defectors, with splendid results. Of the hundred North Koreans Demick says she interviewed in South Korea, we meet six: a young kindergarten teacher whose aspirations were blocked by her father's prewar origins in the South ("tainted blood"); a boy of impeccable background who made the leap to university in Pyongyang and whose impossible romance with the kindergarten teacher forms the book's heart; a middle-age factory worker who is a model communist, a mother of four and the book's soul; her daughter; an orphaned young man; and an idealistic female hospital doctor, who looked on helplessly as the young charges in her care died of hunger during the 1996-99 famine. -

Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Thomas Stock 2018 © Copyright by Thomas Stock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 by Thomas Stock Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Namhee Lee, Chair Where lie the origins of North Korean ideology? When, why, and to what extent did North Korea eventually pursue a path of ideological independence from Soviet Marxism- Leninism? Scholars typically answer these interrelated questions by referencing Korea’s historical legacies, such as Chosŏn period Confucianism, colonial subjugation, and Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla experience. The result is a rather localized understanding of North Korean ideology and its development, according to which North Korean ideology was rooted in native soil and, on the basis of this indigenousness, inevitably developed in contradistinction to Marxism-Leninism. Drawing on Eastern European archival materials and North Korean theoretical journals, the present study challenges our conventional views about North Korean ideology. Throughout the Cold War, North Korea was possessed by a world spirit, a Marxist- Leninist world spirit. Marxism-Leninism was North Korean ideology’s Promethean clay. From ii adherence to Soviet ideological leadership in the 1940s and 50s, to declarations of ideological independence in the 1960s, to the emergence of chuch’e philosophy in the 1970s and 80s, North Korea never severed its ties with the Marxist-Leninist tradition. -

Anecdotes of Kim Jong Il's Life 2

ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA JUCHE 104 (2015) At the construction site of the Samsu Power Station (March 3, 2006) At the Migok Cooperative Farm in Sariwon (December 3, 2006) At the Ryongsong Machine Complex (November 12, 2006) In a fish farm at Lake Jangyon (February 6, 2007) At the Kosan Fruit Farm (May 4, 2008) At the goat farm on the Phyongphung Tableland in Hamju County (August 7, 2008) With a newly-wed couple of discharged soldiers at the Wonsan Youth Power Station (January 5, 2009) At the Pobun Hermitage in Mt. Ryongak (January 17, 2009) At the Kumjingang Kuchang Youth Power Station (November 6, 2009) CONTENTS 1. AFFECTION AND TRUST .......................................................1 “Crying Faces Are Not Photogenic”........................................1 Laughter in an Amusement Park..............................................2 Choe Hyon’s Pistol ..................................................................3 Before Working Out the Budget ..............................................5 Turning “100m Beauty” into “Real Beauty”............................6 The Root Never to Be Forgotten..............................................7 Price of Honey .........................................................................9 Concrete Stanchions Removed .............................................. 10 -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

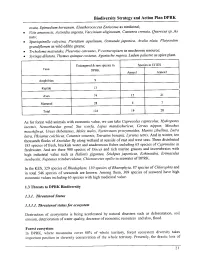

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Dpr Korea 2019 Needs and Priorities

DPR KOREA 2019 NEEDS AND PRIORITIES MARCH 2019 Credit: OCHA/Anthony Burke Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA PART I: TOTAL POPULATION PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED 25M 10.9M 3.8M REQUIREMENTS (US$) # HUMANITARIAN PARTNERS 120M 12 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA 1 PART I: TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: COUNTRY STRATEGY Foreword by the UN Resident Coordinator 03 Needs and priorities at a glance 04 Overview of the situation 05 2018 key achievements 12 Strategic objectives 14 Response strategy 15 Operational capacity 18 Humanitarian access and monitoring 20 Summary of needs, targets and requirements 23 PART II: NEEDS AND PRIORITIES BY SECTOR Food Security & Agriculture 25 Nutrition 26 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 27 Health 28 Guide to giving 29 PART III: ANNEXES Participating organizations & funding requirements 31 Activities by sector 32 People targeted by province 35 People targeted by sector 36 2 PART I: FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR In the almost four years that I have been in DPR Korea Despite these challenges, I have also seen progress being made. -

North Korea-Japan Relations in the Post-Cold War Era

North Korea-Japan Relations in the Post-Cold War Era Titus North Introduction In the spring of 1992 I published an Article in the South Korean government-backed journal Korea and World Affairs on the succession problem in North Korea in which I detailed misrule of the North Korean government and the harsh and oppressed conditions under which the citizens of that country live. Then a decade later on a live radio debate on Radio Nippon I was accused of being a "North Korean agent" by the Japanese parliamentarian Hirasawa Katsuei for having called for Japan to open direct, high-level negotiations with Pyongyang aimed at settling their outstanding differences and establishing diplomatic relations. One might wonder what had snapped in order to transform me from a South Korean flunky to a North Korean agent, but my reading of the situation has not changed at all. What has happened it that the international environment and the attitude of the United States have changed dramatically. The demilitarized zone on the Korean peninsula was one of the front lines during the Cold War, and any transgression across it by either side was liable to set off World War III, thus there was no military solution for Korea, only a possible military nightmare. When the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union broke up, North Korea lost a vital source of cheap energy and raw materials, putting its economy into a tailspin. Meanwhile, Kim Il-sung, the only leader the republic had ever known, was aging and obviously on his way out, leaving behind his untested son. -

Leadership Training for North Korean Defectors

From One “Great Leader” to Many Leaders Who Are Truly Great: Leadership Training for North Korean Defectors Hyun Sook Foley Regent University This article explores Ju-che, the official ideology of North Korea, as an intentional inhibitor of leadership development among North Korean citizens. Ju-che is best understood as a religion idolizing Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il, who are identified as the “mind” of North Korea, with citizens serving as the body and as “human bombs” sworn to protect the Kims. The Confucian concept of “hyo,” or filial piety, is reconceived to apply no longer to biological parents but only to the Kims as the progenitors of a new and eternal revolutionary family—one where civic adolescence and obedience are extolled and independent choice is vilified. A growing number of defectors to South Korea form a leadership laboratory for studying how North Koreans can be equipped to grow to their full potential as leaders. Attempts to swap the Ju-che ideology for a different leadership theory will be insufficient, since Ju-che is a comprehensive worldview. Though unemployment is high and professional employment is low among defectors, training programs like Seoul USA’s Underground University suggest that a comprehensive strategy of teaching leadership from within the Ju-che framework rather than discarding or ignoring it may prove most effective in promoting leadership growth among North Koreans. orth Korea constitutes a fascinating study for leadership theory in that its Ju-che ideological system institutionalizes the recognition -

General Secretary Kim Jong Ungives Field Guidance Over Riverside

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea No. 34 (3 174) weekly http://www.pyongyangtimes.com.kp e-mail:[email protected] Sat, August 21, Juche 110 (2021) General Secretary Kim Jong Un gives field guidance over riverside terraced houses building project Kim Jong Un, most convenient general secretary and hygienic of the Workers’ environment can Party of Korea be provided for and president of the people. He the State Affairs also pointed to the of the DPRK, need to make the gave on-the-spot configurations of guidance over the cities and towns construction of the diverse, attractive Pothong Riverside and unique so as Terraced Houses to create features District. peculiar to each of He was greeted them. on the spot by Jong Saying that it Sang Hak, Jo Yong would be good to Won, Ri Hi Yong give the district and other senior the administrative officials of the division name Central Committee “Kyongru-dong” of the Party and meaning a beau- c o m m a n d i n g tiful gem terrace, officers and leading he gave an officials of the instruction for the units involved in relevant sector to the construction. deliberate on it. He learned about He expressed the construction great satisfaction project as he over the fact that looked round several places of the viewpoint of architectural beauty. Calling for carefully making a radical change has been brought construction site. He said that the project should and implementing a plan for urban about in the riverside area to leave He said that the residential district, be pushed as scheduled by taking construction for raising the level no traces of some 140 days ago, built with the land undulations timely measures for the supply of of modernization and civilization despite lack of everything and left intact, looks nice, and that an equipment and materials in keeping of the capital city and local cities difficulties, thanks to the builders’ example has been set for a terraced with the rapid progress of the and towns, he underscored the patriotism and loyalty, and highly houses district that is built on sloping project.