North Korea Development Report 2002/03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UN Consolidated Relief Appeal 2004

In Tribute In 2003 many United Nations, International Organisation, and Non-Governmental Organisation staff members died while helping people in several countries struck by crisis. Scores more were attacked and injured. Aid agency staff members were abducted. Some continue to be held against their will. In recognition of our colleagues’ commitment to humanitarian action and pledging to continue the work we began together We dedicate this year’s appeals to them. FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON HTTP://WWW.RELIEFWEB.INT/ UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, November 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................11 Table I. Summary of Requirements – By Appealing Organisation ........................................................12 2. YEAR IN REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................13 2.1 CHANGES IN THE HUMANITARIAN SITUATION ...........................................................................................13 2.2 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW...........................................................................................................................14 2.3 MONITORING REPORT AND -

Exhibition Inscriptions

Photographs Prison/Concentration Camps Foreigners are closely followed at all times and are prohibited from leaving their hotels North Korea currently operates sixteen confirmed concentrations camps where up to at night. Photographs are only allowed in a small number of state-approved locations and 200,000 men, women and children are incarcerated. Some are the size of cities and mortality under no circumstances may they be taken of military personnel. In order to document real rates are high since prisoners are forced to perform dangerous slave work and are regularly life in North Korea, Daoust made use of a hidden shutter-release cable to take photographs tortured. Note: Many of those imprisoned are not guilty of any real crime: one man was sent secretly in the non-approved locations. to prison for ten years for absent-mindedly using a newspaper printed with a photograph of Kim Jong-Il to mop up a spilled drink. Pleasure Brigade Bicycles The Kippumjo or Gippeumjo (translated variously as Pleasure Squad, Pleasure Brigade or The late Kim Jong Il reportedly felt that the sight of a woman on a bike was potentially Joy Division) is an alleged collection of groups of approximately 2,000 women and girls dam-aging to public morality. It was the last straw when, in the mid nineties, the daughter of that is maintained by the head of state of North Korea for the purpose of providing pleasure, a top general was killed on a bike. From this point forward, the law has periodically banned mostly of a sexual nature, and entertainment for high-ranking Workers’ Party of Korea women from riding bicycles and they are generally restricted from holding driving licenses. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

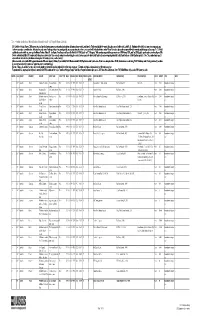

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

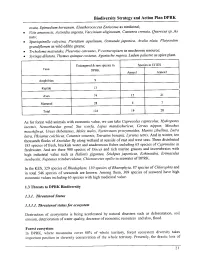

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Liberation Day Short Tour

Liberation Day Short Tour TOUR August 13th – 19th 2021 4 nights in North Korea + Beijing-Pyongyang travel time OVERVIEW Head into the DPRK during Liberation Day for what promises to be one of the best travel experiences you’ll have ever had! During this short but action-packed tour, we have a city tour of Pyongyang, visiting all of the must-see attractions, including the Juche Tower and Mansudae Grand Monument Liberation Day 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the end of Japanese occupation. It is a major public holiday in North Korea and we give you the chance to spend the day joining in the celebrations by hanging out and dancing with the locals in Moranbong Park. As well as the Liberation Day festivities and a city tour of Pyongyang, this tour also includes a day-trip to Kaesong where we visit the DMZ! This is the North-South Korean border, labelled as one of the "most dangerous" borders in the world. See for yourself! Got more time to spare? Stay a couple of days longer for our Liberation Day Tour and see the International Friendship Exhibition. THIS DOCUMENT CANNOT BE TAKEN INTO KOREA The Experts in Travel to Rather Unusual Destinations. [email protected] | +86 10 6416 7544 | www.koryotours.com 27 Bei Sanlitun Nan, Chaoyang District, 100027, Beijing, China DAILY ITINERARY AUGUST 12 – THURSDAY Briefing Day and Train Departure Day *Pre-Tour Briefing | We require all travellers to attend a pre-tour briefing that covers regulations, etiquette, safety, and practicalities for travel in North Korea. The briefing lasts approximately one hour followed by a question and answer session. -

Also Known As the Democratic People's Republic of Korea

CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background North Korea (also known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) is one of the world’s last remaining communist countries. The Juche ideology created by Kim Il-Sung, preserved by his son, Kim Jong-Il, makes it one of the most isolated countries. DPRK’s insistence on self-sufficiency since the 1950s has seen their neighbours, South Korea (also known as Republic of Korea, ROK), over take them in terms of gross national income (GNI) and per capita income, as well as become one of the world’s leading technologically advanced countries. Production efficiency in the factories declined due to a lack of work incentives, agricultural fields remained barren due to shortage of fertilizers, and the transport distribution system collapsed due to decrepit infrastructure. Their closest ally, China, is beginning to be exasperated by DPRK’s constant threats of developing nuclear weapons in exchange for humanitarian aid and economic incentives. The health of Kim Jong-Il remains a great concern for those countries that follow with great interest with the developments in the Korean Peninsula. Countries, including China, and the United States of America (USA), ROK, Japan, and Russia all have important stakes should DPRK collapse suddenly. The top echelon of this anarchical hierarchy is only concerned about political survival and economic gains. This can be seen by the occasional announcements of foreign investments in strategic parts of DPRK using special economic zones (SEZs) such as Kaesong and Rajin-Sonbong. The former being part of the unsuccessful ‘Sunshine Policy’ signed with the late ROK 1 President, Kim Dae-Jung. -

Pyongyang Marathon Short Tour from Shanghai

Pyongyang Marathon Short Tour from Shanghai TOUR April 8th – 13th 2022 2.5 nights in North Korea + Shanghai-Pyongyang travel time OVERVIEW Visit North Korea from Shanghai for the Pyongyang Marathon, one of the most unique marathons in the world! This long weekend adventure packs in the main North Korea attractions with one of the liveliest events of the year. It may be quick, so brace yourself for an action- packed, comprehensive tour. We won't leave without visiting Pyongyang's highlights including; the Pyongyang Metro, one of the deepest subway systems in the world, the Mansudae Grand Monument, the massive bronze statues of the DPRK leadership in downtown, and the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, the country's museum to the Korean War and where you can climb aboard the captured US spy ship the USS Pueblo. This tour will even get you down to historic Kaseong, capital of the medieval Koryo Dynasty, for a tour of the DMZ featuring Panmunjom and the Joint Security Area. ➤ Pyongyang Marathon 2022 Koryo Tours are the official partners of the Pyongyang Marathon. The marathon is a World Athletics’ Bronze Label Road Race, and also has AIMS Certification. Join the race and receive the most unique finisher's medal, running shirt, and race certificates available. Even if you're not a serious runner, the Pyongyang Marathon is an event like no other. It starts and ends in Kim Il Sung Stadium - a stadium filled with over 50,000 North Koreans cheering you on as you finish your race. It's an experience like no other. -

Setting Devotion to People at Core of WPK's Activities

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea No. 32 (3 172) weekly http://www.pyongyangtimes.com.kp e-mail:[email protected] Sat, August 7, Juche 110 (2021) LEAD PATRIOT Setting devotion to people at Nation blessed with core of WPK’s activities growing number of patriots Meritorious persons of Kim Jong Il made sure that It is the supreme principle of always went deeper among the day in August 2018, saying he socialist patriotism are found the people across the country activities of the Workers’ Party people to become their firm would only feel at ease when everywhere in the DPRK which learned after the spiritual world of Korea to steadily improve the spiritual pillar and share weal he rode it first, and examined is seething with enthusiasm of Hero Jong Song Ok and, at people’s material and cultural and woe near them and devoted handles and other fittings one for implementing the first-year the same time, put forward standards of living. everything for their wellbeing by one. tasks of the new five-year plan. frontrunners in various fields as The Third Plenary Meeting of whenever they were in trouble. When new streets and leisure They are unassumingly leaving heroes of the times. the Eighth Central Committee One day in September facilities such as Changjon, indelible marks of their life The Korean people cultivated of the WPK held last June 2020 when the General Mirae Scientists and Ryomyong in the building of a thriving their minds in the days of severe discussed as its major agenda Secretary inspected Kangbuk- streets and the Munsu Water country with their intense trials as they learned the noble items the issues of protecting ri of Kumchon County, North Park were under construction, loyalty, clean conscience and spirit of the chairwoman of the the life and safety of the people, Hwanghae Province, which was he visited the construction sites untiring devotion and passion. -

By Kim, Kook-Hun a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor Of

THE NORTH KOREAN PEOPLE'S ARMY: ITS RISE AND FALL, 1945-1950 by Kim, Kook-Hun A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London King's College London August 1989 ProQuest Number: 11010462 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010462 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The North Korean People's Army: Its Rise and Fall. 1945-1950 The aim of this thesis is to look into the structural, ideological and strategic features of the (North) Korean People's Army from its birth in late 1945 to the debacle in late 1950, thereby forming a coherent and up-to-date account of the early KPA, which is essential to a proper enquiry into the origins and character of the Korean War. The cadre members of the KPA were from three origins: the Soviet- affiliated Kim IISung group; the Yenan group, the returnees from China; and the Soviet-Korean group, a functionary group of the Soviet occupation authorities. -

Korea's Economy

2016 Overview and Macroeconomic Issues Lessons from the Economic Development Experience of South Korea Danny Leipziger The Role of Aid in Korea's Development Lee Kye Woo Future Prospects for the Korean Economy Jung Kyu-Chul Building a Creative Economy The Creative Economy of the Park Geun-hye Administration Cha Doo-won The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses ECONOMY VOLUME 31 KOREA’S Robert D. Atkinson Spurring the Development of Venture Capital in Korea Randall Jones Economic Relations with Europe KOREA’S ECONOMY Korea’s Economic Relations with the EU and the Korea-EU FTA a publication of the Korea Economic Institute of America Kang Yoo-duk VOLUME 31 and the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy 130 Years between Korea and Italy: Evaluation and Prospect Oh Tae Hyun 2014: 130 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Korea and Italy Angelo Gioe 130th Anniversary of Korea’s Economic Relations with Russia Jeong Yeo-cheon North Korea The Costs of Korean Unification: Realistic Lessons from the German Case Rudiger Frank President Park Geun-hye’s Unification Vision and Policy Jo Dongho Korea Economic Institute of America Korea Korea Economic Institute of America 1800 K Street, NW Suite 1010 Washington, DC 20006 CONTENTS KEI Board of Directors ................................................................................................................................ iv KEI Advisory Council .................................................................................................................................. -

North Korea Development Report 2003/04 Price USD 12 the North Korea the North Korea Korea Korea in Both Korean and English

Development Report 2003/04 North North Korea Development Report 2003/04 Korea North Korea Development Report As a result of North Korea’s isolation from the outside world, international communities know little about the status of the North Korean economy and its management mechanisms. Although Recently, a few recent changes in North Korea’s economic system have attracted international interests, but there is much confusion remains as to the characteristics of North Korea’s recent policy changes and its future direction due to the lack of information. Therefore, in order to increase the 2003/04 understanding of readers in South Korea and abroad, KIEP is releasing The North Korea Development Report in both Korean and English. The motivation behind this report stemmed from the need for a comprehensive and systematic investigation into North Korea’s socio-economic conditions, while presenting the current status of its industrial K sectors and inter-Korean economic cooperation. The publishing of this second volume K Y is important because it not only supplements the findings of the first edition, but also Y M updates the recent changes in the North Korean economy. The topics in this report M C include macroeconomics and finance, industry and infrastructure, foreign economic C relations and inter-Korean economic cooperation, social welfare and science & technology. This report also covers the ‘July 1 Economic Reform’ launched two years ago and subsequent changes in the economic management system. The North Korea Development Report helps to improve the understanding of the contemporary North Korean economy. 300-4 Yomgok-dong, Seocho-gu, Seoul 137-747 Korea Tel.