H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'Total War' of Decolonization? Social Mobilization and State-Building In

War & Society ISSN: 0729-2473 (Print) 2042-4345 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ywar20 A ‘Total War’ of Decolonization? Social Mobilization and State-Building in Communist Vietnam (1949–54) Christopher Goscha To cite this article: Christopher Goscha (2012) A ‘Total War’ of Decolonization? Social Mobilization and State-Building in Communist Vietnam (1949–54), War & Society, 31:2, 136-162, DOI: 10.1179/0729247312Z.0000000007 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/0729247312Z.0000000007 Published online: 12 Nov 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 173 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ywar20 Download by: [Université du Québec à Montréal], [Maxime Cédric Minne] Date: 07 January 2017, At: 03:38 war & society, Vol. 31 No. 2, August, 2012, 136–62 A ‘Total War’ of Decolonization? Social Mobilization and State-Building in Communist Vietnam (1949–54) Christopher Goscha Professor of International Relations, Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada By choosing to transition to modern, set-piece battle during the second half of the Indochina War, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) created one of the most socially totalizing wars in order to meet that ambitious goal. This article argues that, while the DRV did indeed create a remarkably mod- ern army of six divisions, the lack of a mechanized logistical system meant that it had to mobilize hundreds of thousands of civilian porters to supply its troops moving across Indochina. To do this, the communist party under- took a massive mobilization drive and simultaneously expanded its efforts to take the state in hand. -

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 17 (October 2017), No. 194 Ben Kiernan, Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. xvi + 621 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $34.95 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-0-1951-6076-5. Christopher Goscha, Vietnam: A New History. New York: Basic Books, 2016. xiv + 553 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $35.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-0-4650-9436-3. K. W. Taylor, A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. xv + 696 pp. Illustrations, maps, bibliography, and index. $49.99 U.S. (pb) ISBN 978-0-5216-9915-0. Review by Gerard Sasges, National University of Singapore. Those of us with an interest in the history of Vietnam should count ourselves lucky. In the space of just four years, three senior historians of Southeast Asia have produced comprehensive studies of Vietnam’s history. After long decades where available surveys all traced their origins to the Cold War, readers are now spoiled for choice with three highly detailed studies based on decades of research by some of the most renowned scholars in their fields: Ben Kiernan’s Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Christopher Goscha’s Vietnam: A New History, and Keith Taylor’s A History of the Vietnamese. Their appearance in such rapid succession reflects many things: the authors’ personal and professional trajectories, the continued interest of publics and publishers for books on Vietnamese history, and important changes in the field of Vietnamese Studies since the 1990s. -

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol

2018 H-Diplo Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse @HDiplo Roundtable and Web Production Editor: George Fujii Introduction by Edward Miller Roundtable Review Volume XIX, No. 45 (2018) 23 July 2018 Geoffrey C. Stewart. Vietnam’s Lost Revolution: Ngô Đình Diệm’s Failure to Build an Independent Nation, 1955-1963. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. ISBN: 9781107097889 (hardback, $99.99). URL: http://www.tiny.cc/Roundtable-XIX-45 Contents Introduction by Edward Miller, Dartmouth College ..............................................................................2 Review by Philip E. Catton, Stephen F. Austin State University .........................................................6 Review by Jessica M. Chapman, Williams College ..................................................................................9 Review by Jessica Elkind, San Francisco State University ................................................................. 11 Review by Van Nguyen-Marshall, Trent University ............................................................................. 14 Author’s Response by Geoffrey C. Stewart, University of Western Ontario ............................... 16 © 2018 The Authors. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License. H-Diplo Roundtable Review, Vol. XIX, No. 45 (2018) Introduction by Edward Miller, Dartmouth College n 1965, as American ground troops poured into South Vietnam and U.S. warplanes rained bombs on North Vietnam, the journalist Robert Shaplen published a book -

Recentering the United States in the Historiography of American Foreign Relations

The Scholar Texas National Security Review: Volume 3, Issue 2 (Spring 2020) Print: ISSN 2576-1021 Online: ISSN 2576-1153 RECENTERING THE UNITED STATES IN THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN FOREIGN RELATIONS Daniel Bessner Fredrik Logevall 38 Recentering the United States in the Historiography of American Foreign Relations In the last three decades, historians of the “U.S. in the World” have taken two methodological turns — the international and transnational turns — that have implicitly decentered the United States from the historiography of U.S. foreign relations. Although these developments have had several salutary effects on the field, we argue that, for two reasons, scholars should bring the United States — and especially, the U.S. state — back to the center of diplomatic historiography. First, the United States was the most powerful actor of the post-1945 world and shaped the direction of global affairs more than any other nation. Second, domestic processes and phenomena often had more of an effect on the course of U.S. foreign affairs than international or transnational processes. It is our belief that incorporating the insights of a reinvigorated domestic history of American foreign relations with those produced by international and transnational historians will enable the writing of scholarly works that encompass a diversity of spatial geographies and provide a fuller account of the making, implementation, effects, and limits of U.S. foreign policy. Part I: U.S. Foreign Relations two trends that have emphasized the former rather After World War II than the latter. To begin with, the “international turn” (turn being the standard term among histo- The history of U.S. -

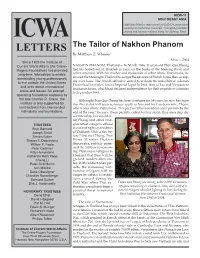

The Tailor of Nakhon Phanom by Matthew Z

MZW-11 SOUTHEAST ASIA Matthew Wheeler, most recently a RAND Corporation security and terrorism researcher, is studying relations ICWA among and between nations along the Mekong River. LETTERS The Tailor of Nakhon Phanom By Matthew Z. Wheeler MARCH, 2004 Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane- NAKHON PHANOM, Thailand— In March 1946, 11-year-old Phan Que Phung Rogers Foundation) has provided fled his hometown of Thakhek in Laos, on the banks of the Mekong River, and long-term fellowships to enable never returned. With his mother and thousands of other ethnic Vietnamese, he outstanding young professionals crossed the Mekong to Thailand to escape the advance of French forces then sweep- to live outside the United States ing over Laos. The French offensive aimed to reclaim the Indochinese colonies France had lost twice, first to Imperial Japan in 1941, then to Lao and Vietnamese and write about international resistance forces, which had declared independence for their respective countries areas and issues. An exempt in September 1945. operating foundation endowed by the late Charles R. Crane, the Although Phan Que Phung has been a refugee for 58 years, he now has hope Institute is also supported by that this status will soon no longer apply to him and his Lao-born wife, Thoan, contributions from like-minded who is also ethnic Vietnamese. “I expect we’ll have resident-alien permits by the individuals and foundations. end of the year,” he says. These permits, called bai tang dao in Thai, are a step shy of citizenship, but would of- fer Phung and other first- TRUSTEES generation refugees official Bryn Barnard status and rights as residents Joseph Battat of Thailand. -

Intelligence in a Time of Decolonization: the Case of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at War (1945–50)

Intelligence in a Time of Decolonization: The Case of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at War (1945–50) CHRISTOPHER E. GOSCHA The renaissance in intelligences studies over the last two decades has offered new and exciting insights into war, societies, ideologies, institutions, and even cultures and mindsets. Yet, its geographical reach has remained largely limited to the West or Western cases. We still know relatively little about intelligence services and their roles in the making of postcolonial nation-states in Africa or Asia, much less their perceptions of the world outside. This article uses the case of communist Vietnam during the First Indochina War to provide a general overview of the birth, development, and major functions of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s Public Security and Intelligence services in a time of decolonization. It then examines three Vietnamese case studies as a way of considering wider themes relating to the question of intelligence and decolonization. In wider terms, this article seeks to contribute to the expansion of intelligence studies on the non- Western,‘postcolonial’ world. INTELLIGENCE STUDIES AND THE POSTCOLONIAL WORLD The renaissance in ‘intelligences studies’ over the last two decades has offered new and exciting insights into war, societies, ideologies, institutions, and even cultures and mindsets. However, since its take-off some two decades ago, its geographical reach has remained largely limited to the West. We still know relatively little about intelligence services and their roles in the making of postcolonial nation-states in Africa or Asia, much less their perceptions of the world outside. This is not surprising. -

Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954-1963)

Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954-1963) By Nu-Anh Tran A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Peter Zinoman, Chair Professor Penny Edwards Professor Kerwin Klein Spring 2013 Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954-1963) Copyrighted 2013 by Nu-Anh Tran Abstract Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954-1963) by Nu-Anh Tran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Peter Zinoman, Chair This dissertation presents the first full-length study of anticommunist nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, 1954-1975, or South Vietnam). Specifically, it focuses on state nationalism during the rule of Ngô Đình Diệm (1954-1963). Conventional research depicts the Vietnam War (1954-1975) as a conflict between foreign intervention and indigenous nationalism, but this interpretation conflates Vietnamese communism with Vietnamese nationalism and dismisses the possibility of nationalism in the southern Republic. Using archival and published sources from the RVN, this study demonstrates that the southern regime possessed a dynamic nationalist culture and argues that the war was part of a much longer struggle between communist and anticommunist nationalists. To emphasize the plural and factional character of nationalism in partitioned Vietnam, the study proposes the concept of contested nationalism as an alternative framework for understanding the war. The dissertation examines four elements of nationalism in the Republic: anticommunism, anticolonialism, antifeudalism, and Vietnamese ethnic identity. The first chapter argues that the government and northern émigré intellectuals established anticommunism as the central tenet of Republican nationalism during the Denounce the Communists Campaign, launched in 1955. -

Vietnam : a New History Bibliography

VIETNAM : A NEW HISTORY BIBLIOGRAPHY Books, Book Chapters, Articles, Theses and conferences. Abuza, Zachary, Renovating Politics in Contemporary Vietnam. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001. Affidi, Emmanuelle, “Créer des passerelles entre les mondes… L’œuvre interculturelle de Nguyen Van Vinh (1882-1936) ”, Moussons, no. 21, (2014), pp. 33-55. Affidi, Emmanuelle, “Vulgarisation du savoir et colonisation des esprits par la presse et le livre en Indochine française et dans les Indes néerlandaises (1908-1936)”, Moussons, nos. 13-14, (2009), pp. 95-121. Ageron, Charles-Robert, “L’Exposition coloniale de 1931: mythe républicain ou mythe impéria l”. In Les lieux de mémoire. La République, edited by Pierre Nora. Paris: Gallimard, 1997 (1st Publication in 1984), pp. 495-515. Ageron, Charles-Robert, “L'opinion publique face aux problèmes de l’Union française (étude de sondages) ”. In Les chemins de la décolonisation de l'Empire français, 1936-1956, directed by Charles-Robert Ageron. Paris: Editions du CNRS, 1986, pp. : 33-48. Ageron, Charles-Robert, France coloniale ou parti colonial? Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1978. Ai Nguyen, Lai and Alec Holcombe, “The Heart and Mind of the Poet Xuan Dieu: 1954–1958”, Journal of Vietnamese Studies 5, no. 2 (Summer 2010), pp. 1-90. Aimaq, Jasmine, “For Europe or Empire?”. Lund: Lund University, 1994. (PhD Thesis). Aldrich, Robert, “Imperial Banishment: French Colonizers and the Exile of Vietnamese Emperors”, French History & Civilization 5, (2014). Available Online at: http://fliphtml5.com/vdxa/dxse Aldrich, Robert, “France’s Colonial Island: Corsica and the Empire”, French History and Civilization: papers from the George Rude Seminar 3, (2009), pp. -

In the Service of World Revolution Vietnamese Communists’ Radical Ambitions Through the Three Indochina Wars

In the Service of World Revolution Vietnamese Communists’ Radical Ambitions through the Three Indochina Wars ✣ Tu o n g Vu Introduction The end of World War II witnessed the rise of many anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa that fueled a global trend of decolonization. Soon this pro- cess became entangled in the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. The connection between the Cold War and decolonization was complex and shaped not only by the superpowers.1 As the United States and USSR sought allies around the world to strengthen their global positions, elites in newly independent countries or those still struggling for indepen- dence pursued their own visions and found ways to make the Cold War serve their interests. In Vietnam more than anywhere else in the postcolonial world, the Cold War and the struggle for national independence became deeply intertwined, with devastating consequence. A Communist-led movement in Vietnam took advantage of the power vacuum in the wake of the Japanese surrender to form a government in late 1945. As the Vietnamese Communists fought a protracted war with France (the “First Indochina War”), they found sup- port in the Soviet bloc, whereas the French and other Western powers em- braced anti-Communist nationalists. After about fifteen years of fierce warfare 1. The best account is Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005). For an Asia-focused review, see Tuong Vu, “Cold War Studies and the Cultural Cold War in Asia,” in Tuong Vu and Wasana Wongsurawat, eds., Dynamics of the Cold War in Asia: Ideology, Identity, and Culture (New York: Pal- grave Macmillan, 2010), esp. -

Contesting Concepts of Space and Place in French Indochina by Christopher E

GOSCHA Offers an innovative concept of space and place that has a wider applicability far beyond Indochina or Vietnam Why, Benedict Anderson once asked, did Javanese become Indonesian in 1945 whereas the Vietnamese balked at becoming Indochinese? In this classic study, Christopher Goscha shows that Vietnamese of all political colours came remarkably close to building a modern national identity based on the colonial model of Indochina while Lao and Cambodian nationalists rejected this Contesting Concepts of Space precisely because it represented a Vietnamese entity. Specialists G and Place in French Indochina of French colonial, Vietnamese, Southeast Asia and nationalism O studies will all find much of value in Goscha’s provocative IN rethinking of the relationship between colonialism and nationalism in Indochina. G First published in 1995 as Vietnam or Indochina? Contesting Con- cepts of Space in Vietnamese Nationalism, this remarkable study has I been through a major revision and is augmented with new material ND by the author and a foreword by Eric Jennings. ‘Goscha’s analysis extends far beyond semantics and space. His range of och sources is dazzling. He draws from travel literature to high politics, maps, bureaucratic bulletins, almanacs, the press, nationalist and communist texts, history and geography manuals and guides, amongst others. … [T]his book remains highly relevant to students of nationalism, Southeast Asia, French INE colonialism, Vietnam, geographers and historians alike.’ – Eric Jennings, University of Toronto S E CHRISTOPHER E. GoschA www.niaspress.dk Goscha-Indochinese_cover.indd 1 06/01/2012 14:21 GOING INDOCHINESE Goscha IC book.indd 1 21/12/2011 14:36 NIAS – Nordic Institute of Asian Studies NIAS Classics Series Scholarly works on Asia have been published via the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies for more than 40 years, the number of titles published ex- ceeding 300 in total. -

Revisionism Triumphant Hanoi's Diplomatic Strategy in the Nixon

AsseHanoilin’sDiplomatic Strategy in the Nixon Era Revisionism Triumphant Hanoi’s Diplomatic Strategy in the Nixon Era ✣ Pierre Asselin Introduction Following the onset of the “Anti-American Resistance for National Salvation” in the spring of 1965, the leaders of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP— the Communist party), which controlled the Democratic Republic of Viet- nam (DRV, i.e., North Vietnam) after partition of the country in 1954, pledged to ªght foreign “aggressors” and their South Vietnamese “lackeys” until they achieved “complete victory” and the “liberation” of the South.1 To those ends, DRV foreign policy was oriented toward securing optimal material support for the war from socialist allies, as well as political support from “progressive” forces worldwide. Intent on “winning everything,” VWP leaders rejected a negotiated settlement of the war.2 Indeed, they would not even agree to peace talks with the enemy because that might signal a lack of resolve on their part to achieve all of their goals.3 They would not “show any weakness,” just as they would “agree to no Munich—no peace with dis- 1. Meeting the goals of the “Anti-American Resistance” was necessary to achieve the objectives of the “Vietnamese Revolution,” which aimed to bring about reuniªcation and socialist transformation of the nation under Communist aegis. 2. Robert S. McNamara, James Blight, and Robert Brigham, Argument without End: In Search of An- swers to the Vietnam Tragedy (New York: Public Affairs, 1999), p. 183, emphasis in original. 3. On the efforts to jumpstart negotiations before 1968, see Luu Van Loi and Nguyen Anh Vu, Tiep xuc bi mat truoc Hoi nghi Pa-ri (Hanoi: Vien quan he quoc te, 1990); David Kraslow and Stuart A. -

The War for Cochinchina, 1945-1951 DISSERTATION Presented In

In the Year of the Tiger: the War for Cochinchina, 1945-1951 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William McFall Waddell III Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John Guilmartin, Professor of History Dr. Peter Mansoor, Gen. Raymond E. Mason Chair in Military History Dr. Alan Beyerchen, Professor of History, Emeritus Copyright by William M. Waddell 2014 ABSTRACT In 1950 the French stake in Indochina experienced two parallel, but very different outcomes. In Tonkin the French military suffered a major catastrophe in the form of the Route Coloniale 4 disaster that nearly unmade the entire French position in the north of Indochina. In the south, in Cochinchina, something very different occurred. A series of resource-constrained, but introspective commanders, built a strong, circumscribed hold over the key economic and political portions of the country. By restraining their effort and avoiding costly attempts at the outright defeat of Viet Minh, the southern French command was able to emerge victorious in a series of violent, concerted, but now largely forgotten actions across 1950. It was, it must be remembered, not just French failure that set the stage for the American intervention in Vietnam, but also the ambiguous nature of French success. ii DEDICATION pour les causes perdues iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the assistance of my thesis advisors, Dr. John Guilmartin, Dr. Peter Mansoor, and Dr. Alan Beyerchen. They have nurtured my interest in and passion for history, and pushed me to think in ways I certainly would not have on my own.