INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

El Rechazo De Las Mujeres Mayores Viudas a Volverse a Emparejar: Cuestión De Género Y Cambio Social”

El rechazo de las mujeres mayores viudas a volver- se a emparejar: cuestión de género y cambio social Juan LÓPEZ DOBLAS Universidad de Granada [email protected] María del Pilar DÍAZ CONDE Universidad de Granada [email protected] Mariano SÁNCHEZ MARTÍNEZ Universidad de Granada [email protected] Recibido: 23-04-2014 Aceptado: 08-06-2014 Resumen: El objetivo de este artículo es indagar sobre las actitudes personas mayores viudas en España respecto a la posibilidad de formar otra pareja, sea celebrando otro matrimonio o conviviendo con alguien sin llegar a casarse. Lo hacemos desde una óptica sociológica, aplicando metodología cualitativa y, en concreto, la técnica del grupo de discusión. De los resultados cabe destacar que iniciar una relación de pareja despierta un interés muy escaso, particularmente entre las mujeres, por diversas razones. Aunque en algunas de ellas influyen valores tradicionales (como, por ejemplo, el no querer poner a nadie en el lugar de su primer marido o el temor a recibir la crítica familiar y social), cuenta tanto o más otra serie de motivaciones (como el renunciar a emparejarse con alguien mayor que ellas, el mantener su libertad y su independencia, la defensa de su autonomía) que permiten entrever la exis- tencia de un importante cambio en el modo en que las mujeres mayores conciben la vejez y las relaciones entre los géneros. Palabras clave: vejez; viudez; mujer; volverse a casar; uniones de hecho; cambio social; metodología cualitativa Política y Sociedad 507 ISSN: 1130-8001 2014, 51, Núm. 2: 507-532 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_POSO.2014.v51.n2.44936 López Doblas El rechazo de las mujeres mayores viudas a volverse a empareja… Older widows refusal to repartnering. -

Un Cuchillo En El Corazón. Gaspar Noé: ¿Cineasta De Un Social Contemporáneo? La Tragedia De Un Hombre (Solo) En La Tragedia Del Siglo

Vladimir Broda Ética & Cine | Vol. 10 | No. 1 | Marzo 2020 - Junio 2020 | pp. 71-86 Un cuchillo en el corazón. Gaspar Noé: ¿cineasta de un social contemporáneo? La tragedia de un hombre (solo) en la tragedia del siglo. Solo contra todos | Gaspar Noé | 1998 Vladimir Broda* Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR04 Recepción: 15 de diciembre de 2019; aceptación: 2 de febrero de 2020 Resumen “¿Cuáles son los límites del tratamiento cinematográfico de la “moral” y la “justicia”? El film de Gaspar Noé “Solo contra todos” tiene la virtud de poner a prueba nuestra capacidad de tolerancia a la emergencia de lo real. ¿Es la violencia de los traumas originales (masacre del padre y abandono de la madre) reparable, o está condenada a repetirse de generación en generación? Las definiciones de moralidad y justicia se ven conmovidas a lo largo de esta película, enmarcada en el corazón de una tragedia histórico-social: la ley simbólica no hace más ley. En estas coordenadas, ¿no está el sujeto condenado a transgredir, incluso en un rescate del “amor”, la ley simbólica de la prohibición del incesto?” Palabras clave: Tragedia Social | Moral | Justicia | Simbólico | Amor | Soledad A knife is born at the heart. Gaspar Noé: filmmaker of a contemporary social? The tragedy of a man (alone) in the tragedy of the century. Abstract What are the limits of the cinematographic treatment of “morals “ and “justice”? Gaspar Noé’s film “ Alone Against All” has the virtue of testing our capacity to tolerate the emergence of the real. Is it the violence of the original traumas (slaughter of the father and abandonment of the mother) repairable, or is it condemned to be repeated from generation to generation? The definitions of morality and justice are moved throughout this film, framed in the heart of a historical-social tragedy: the symbolic law makes no more law. -

Religion & Spirituality in Society Religión Y Espiritualidad En La

IX Congreso Internacional sobre Ninth International Conference on Religión y Religion & Espiritualidad en Spirituality in la Sociedad Society Símbolos religiosos universales: Universal Religious Symbols: Influencias mutuas y relaciones Mutual Influences and Specific específicas Relationships 25–26 de abril de 2019 25–26 April 2019 Universidad de Granada University of Granada Granada, España Granada, Spain La-Religion.com ReligionInSociety.com Centro de Estudios Bizantinos, Neogriegos y Chipriotas Ninth International Conference on Religion & Spirituality in Society “Universal Religious Symbols: Mutual Influences and Specific Relationships” 25–26 April 2019 | University of Granada | Granada, Spain www.ReligionInSociety.com www.facebook.com/ReligionInSociety @religionsociety | #ReligionConference19 IX Congreso Internacional sobre Religión y Espiritualidad en la Sociedad “Símbolos religiosos universales: Influencias mutuas y relaciones específicas” 25–26 de abril de 2019 | Universidad de Granada | Granada, España www.La-Religion.com www.facebook.com/ReligionSociedad @religionsociety | #ReligionConference19 Centro de Estudios Bizantinos, Neogriegos y Chipriotas Ninth International Conference on Religion & Spirituality in Society www.religioninsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact [email protected]. Common Ground Research Networks may at times take pictures of plenary sessions, presentation rooms, and conference activities which may be used on Common Ground’s various social media sites or websites. -

Gabriel Gacía Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez El coronel no tiene quien le escriba Gabriel García Márquez (Aracataca, Colombia, 1928) es la figura más representativa de lo que se ha venido a llamar el «realismo mágico» hispanoamericano. Aún antes de escribir Cien años de soledad (novela ya publicada por El Mundo en la colección Millenium I), donde recrea la geografía imaginaria de Macondo, un lugar aislado del mundo en el que realidad y mito se confunden, era ya autor de un conjunto de obras que tienen directa relación con esta narración. Otras obras memorables son: El coronel no tiene quien le escriba, El otoño del patriarca, Crónica de una muerte anunciada (volumen número 5 de esta colección), El amor en los tiempos del cólera y varias colecciones de cuentos magistrales. En 1982 recibió el Premio Nobel de Literatura. Consideradas a veces las obras anteriores a Cien años de soledad como acercamiento o tentativa de la gran novela que habría de llegar, cada vez más la crítica subraya el valor que, en sí mismos, poseen esos títulos tempranos, que no primerizos, de García Márquez, por encima de los elementos que los conectan con su gran novela. Tal es el caso de El coronel no tiene quien le escriba, segundo de sus libros. «Sería un error descartarlos como intentos frustrados; particularmente El coronel no tiene quien le escriba es una pequeña obra maestra del estilo condensado de García Márquez» (José Miguel Oviedo). Con todo, y dada la fuerza del mundo macondino del autor, es difícil sustraerse a señalar semejanzas y diferencias entre ambos títulos. En El coronel no tiene quien le escriba ya hay un germen de desmesura, concretamente en lo que al tiempo se refiere (esa larga espera del protagonista por su pensión siempre demorada); está, desde luego, el tema de la soledad; las reiteraciones de ciertos elementos, las guerras como telón de fondo, el simbolismo de algunos objetos (o animales: el gallo, que es la herencia del hijo muerto). -

The New Economy and Jobs/Housing Balance in Southern California

The New Economy and Jobs/Housing Balance in Southern California Southern California Association of Governments 818 West 7th Street, 12th Floor Los Angeles, California 90017 April 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROJECT MANAGEMENT James Gosnell, Director, Planning and Policy Development Joseph Carreras, Principal Planner AUTHORS Michael Armstrong, Senior Planner Brett Sears, Associate Planner With research support from Frank Wen, Senior Economist TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Mary Jane Abare, GIS Systems Analyst Mark Butala, Associate Planner Bruce Devine, Chief Economist James Jacob, Acting Manager, Social and Economic Data Forecasting Jacob Lieb, Senior Planner Javier Minjares, Senior Planner The New Economy and Jobs/Housing Balance in Southern California 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TOPIC PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 TABLES, FIGURES, AND MAPS 5 ABSTRACT 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 I. INTRODUCTION 11 II. DEFINITION OF JOBS/HOUSING BALANCE 15 III. BENEFITS OF JOBS/HOUSING BALANCE 19 A. Reduced Congestion and Commute Times 19 B. Air Quality Benefits 19 C. Economic and Fiscal Benefits 19 D. Quality of Life Benefits 20 IV. ANALYSIS OF REGIONAL JOBS/HOUSING BALANCE ISSUES 21 A. Current (1997) and Forecast (2025) Jobs/Housing Ratios 21 1. Overview 21 2. Analysis Results 21 B. The Household Footprint and the Jobs/Household Footprint 31 1. Overview 31 2. Analysis Results 31 C. Development Capacity of 1993/1994 General Plans and Zoning to Accommodate Housing and Employment Demand 35 1. Overview 35 2. Analysis Results 36 D. Summary of Regional Jobs/Housing Balance Issues 37 V. DYNAMICS OF JOBS/HOUSING BALANCE 39 A. The New Economy 39 1. Bay Area Experience 39 2. Santa Barbara Experience 42 3. -

Hombre Al Agua

HOMBRE AL AGUA Robert Sheckley Título original: The man in the water Traducción: Fernando Velasco © 1962; Robert Sheckley © 1971; Editorial Noguer. Colección Esfinge, nº 18 Edición digital de J. M. C. Febrero de 2003. 2 Contraportada: Dos hombres se encuentran solos en un velero inmovilizado por la bonanza en el Mar de los Sargazos, a medio camino entre St. Thomas, de donde ha partido, y las Bermudas. Uno es un viejo lobo de mar, duro y astuto, el otro un joven sin carácter, débil y pusilánime, que sólo aspira a demostrar que no es una nulidad. Su problema consiste en cómo demostrarlo. Y para ello, su mente enfermiza sólo concibe un camino: el del crimen. Sin embargo, para cometer un asesinato hace falta algo más que el deseo de ejecutarlo. Sobre todo cuando la realidad es irreal, alucinante y fantástica, y cuando la fantasía puede convertirse en realidad. ¿O es acaso una realidad ofuscada por la fantasía? Con el mar como testigo, la calma enloquecedora, un sol de justicia y la negrura de la noche, los hechos se descomponen en un mosaico cuyos elementos se trastocan y superponen en una ausencia total de lógica y continuidad. La alucinante y sobrecogedora historia tiene un ritmo espasmódico que no ofrece tregua al protagonista ni al lector, y cuyo final es de todo punto sorprendente y por lo lógico e inesperado a la vez. El autor, Robert Sheckley, nacido en Nueva York en 1928 de una familia de emigrantes rusos, comenzó desde muy joven su carrera de escritor, destacando en seguida como uno de los más originales creadores de novelas de ciencia-ficción. -

Esperando a Godot (Pdf)

Samuel Beckett Esperando a Godot Traducción de Ana María Moix 1º Edición: Mayo de 2005 2º Edición: Marzo de 2006 3ª Edición: Diciembre de 2006 Colección: El Ojo del Magma Catálogo Interno: LIT [Literatura] Diseño de Tapa: Cro. Ernoino La reproducción total o parcial de este libro y todo el conjunto de técnicas colectivas que se han aplicado en su producción no esta prohibida por los editores sino alentada y apoyada. Los Editores se han apropiado de este producto de la humanidad y lo entregan a toda la comunidad bajo las directivas de la GPL y el Copyleft. 2006 (Copyleft) Editorial Último Recurso Rosario - Sta. Fe Impreso en Argentina 2 ACTO PRIMERO (Camino en el campo, con árbol) (Anochecer) (Estragon, sentado en el suelo, intenta descalzarse. Se esfuerza haciéndolo con ambas manos, fatigosamente. Se detiene, agotado, descansa, jadea, vuelve a empezar. Repite los mismo gestos) (Entra Vladimir) ESTRAGON (renunciando de nuevo): No hay nada que hacer VLADIMIR (se acerca a pasitos rígidos, las piernas separadas): Empiezo a creerlo. (Se queda inmóvil) Durante mucho tiempo me he resistido a pensarlo, diciéndome, Vladimir, sé razonable, aún no lo has intentado todo. Y volvía a la lucha. (Se concentra, pensando en la lucha. A Estragon) Vaya, ya estás ahí otra vez. ESTRAGON: ¿Tú crees? VLADIMIR: Me alegra volver a verte. Creí que te habías ido para siempre. ESTRAGON: Yo también. VLADIMIR: ¿Qué podemos hacer para celebrar este encuentro? (Reflexiona) Levántate, deja que te abrace. (Tiende la mano a Estragon) ESTRAGON (irritado): Enseguida, enseguida. (Silencio) VLADIMIR (ofendido, con frialdad): ¿Se puede saber dónde ha pasado la noche señor? 3 ESTRAGON: En un foso. -

The Beauties of Lucknow: an Urdu Photographic Album

Journal of Journal of urdu studies 1 (2020) 141-176 URDU STUDIES brill.com/urds The Beauties of Lucknow: An Urdu Photographic Album Kathryn Hansen Professor Emeritus, Department of Asian Studies, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA [email protected] Abstract ʿAbbās ʿAlī of Lucknow published several volumes of photographs which were unique in being accompanied by text in English and Urdu. The Beauties of Lucknow (1874), an album of female performers and costumed actors from the Indar Sabhā, is attributed to him. Based on examination of the rare book in five archival locations, this article accounts for the variations among them. It distinguishes between the photographer’s authorial intentions and the agency of artisans, collectors, and others who altered the artifact at various stages. Comparison of the textual apparatus of the English and Urdu editions reveals the author’s mode of address to different audiences. The Urdu intro- duction, saturated with poetic tropes, provides insight into ways of viewing photo- graphs as formulated among the local cognoscenti. The article proposes that ʿAbbās ʿAlī’s book was meant as a private gift, as well as a publication for wider circulation. Keywords History of photography – ʿAbbās ʿAlī – Lucknow – female performers – Urdu theatre and drama 1 Introduction In 2014, a set of images from The Beauties of Lucknow, an Indian photographic album published in 1874, appeared online in Tasveer Journal from Bangalore. These photographs revived interest in early portraits of courtesans from the subcontinent, a topic of perennial fascination. The inclusion of costumed © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/26659050-12340011 142 Hansen actors from a well-known work of Urdu musical theatre, Indar Sabhā (The Assembly of King Indar), was particularly compelling. -

Quinientas Mujeres Para Un Hombre Solo

PF. LOT MUJERES lABi C» •uB&B .WO la fié lotti?. RICARDO COVARRUBIAS j - °L> óc - "" > ií- ! W w Me \-.hA mk # I - . QUINIENTAS MUJERES PARA UN HOMBRE SOLO Cías. Amo, .1 --- -V. edenei C,8 vfieó Cgu «'oQ6 \ jr— • y M ADOLFO BELOT QUINIENTAS^ MUJERES JFî- v: . UN HOMBRE SOLO VERSIÓN CASTELLANA V'v. DE # EL COSMÓS. EDITORIAL _ - O CRI CB JNlVERfflDAD DE Ntf€VO lEOft BIBLIOTECA 'wmo Rï'ko" «ME. 1625 MONTERREY, MEXÎCP MADRID EL COSMOS EDITORIAL "'»HCOTWS-SITITA MI3TFÍ-,"4V ^MU**'1"" ' ' O-^Ï JA A 'J J S 1890 ésaAnfr^fim ¿OTO? - J . H . A «KfiSat (àu*! m ©si ìà Es propiedad. Queda hecho el depósi- FONDO to que marea la ley. RICARDO OOVARRUBIAS _ cV* • - « CAPILLA ALFONSINA BIBLIOTECA UNJV£T^rrARIA Madrid.—Imprenta do Fortanet, Libertad, 29. V . A. N . L: QUINIENTAS MUJERES UN HOMBRE: SOLO -¿MBWD BEÙvmlr:, biblioteca IP /! WimJ UN PROYECTO Isidoro, Clementinay Celestino Girodot en el país de las Treinta-y-seis Bestias Tengo el propósito de narrar muy pronto mi viaje de París á Cochinchina, en forma nueva tal vez, dejando gran parte á la fantasía y al buen humor, sin apartarme, no obstante, de la verdad cuando se trate de pintar los países que he visitado y las costumbres de sus habi- tantes. A fin de dar más interés á mi relato, me ocul- taré todo lo posible, y dejaré hacer y hablar á un hombre muy conocido en el barrio del Odeon no de bitácora de á bordo y algunas notas que y de la Comedia Francesa, á Isidoro Girodot, á he tomado en el viaje. -

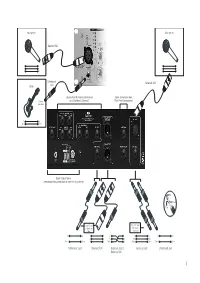

Balanced XLR Unbalanced Jack Digital Output Option (See Separate

Microphone Microphone Balanced XLR 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 Unbalanced Balanced XLR Guitar Jack Latency-Free Monitoring connections Insert connections (see Guitar or (see 'Facilities & Controls') 'Rear Panel Connections') bass output Tip Tip Sleeve Sleeve Digital Output Option (see separate documentation for connection guidance) To Line I/P, Tape I/P From synth output, or Mixer Insert mixer output or Return insert send 1 ENGLISH CONTENTS IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................2 Please read all of these instructions and save them for future reference. Follow all warnings and instructions marked on the unit. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS...................................................................2 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................3 • Do not obstruct air vents in the rear panel. Do not insert objects through any apertures. GETTING TO KNOW THE UNIT ...............................................................................3 • Do not use a damaged or frayed power cord. REAR PANEL CONNECTIONS...................................................................................3 • Unplug the unit before cleaning. Clean with a damp cloth only. Do not spill liquid on the unit. GETTING STARTED ......................................................................................................4 • Ensure adequate airflow around the unit -

Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 Maya Jiménez The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2151 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COLOMBIAN ARTISTS IN PARIS, 1865-1905 by MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Katherine Manthorne____ _______________ _____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Kevin Murphy__________ ______________ _____________________________ Date Executive Officer _______Professor Judy Sund________ ______Professor Edward J. Sullivan_____ ______Professor Emerita Sally Webster_______ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 by Maya A. Jiménez Adviser: Professor Katherine Manthorne This dissertation brings together a group of artists not previously studied collectively, within the broader context of both Colombian and Latin American artists in Paris. Taking into account their conditions of travel, as well as the precarious political and economic situation of Colombia at the turn of the twentieth century, this investigation exposes the ways in which government, politics and religion influenced the stylistic and thematic choices made by these artists abroad.