Riddle of Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Award Winning Books(Available at Klahowya SS Library) Michael Printz, Pulitzer Prize, National Book, Evergreen Book, Hugo, Edgar and Pen/Faulkner Awards

Award Winning Books(Available at Klahowya SS Library) Michael Printz, Pulitzer Prize, National Book, Evergreen Book, Hugo, Edgar and Pen/Faulkner Awards Updated 5/2014 Michael Printz Award Michael Printz Award continued… American Library Association award that recognizes best book written for teens based 2008 Honor book: Dreamquake: Book Two of the entirely on literary merit. Dreamhunter Duet by Elizabeth Knox 2014 2007 Midwinter Blood American Born Chinese (Graphic Novel) Call #: FIC SED Sedgwick, Marcus Call #: GN 741.5 YAN Yang, Gene Luen Honor Books: Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets Honor Books: of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz; Code Name The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to Verity by Elizabeth Wein; Dodger by Terry Pratchett the Nation; v. 1: The Pox Party, by M.T. Anderson; An Abundance of Katherines, by John Green; 2013 Surrender, by Sonya Hartnett; The Book Thief, by In Darkness Markus Zusak Call #: FIC LAD Lake, Nick 2006 Honor Book: The Scorpio Races, by Maggie Stiefvater Looking for Alaska : a novel Call #: FIC GRE Green, John 2012 Where Things Come Back: a novel Honor Book: I Am the Messenger , by Markus Zusak Call #: FIC WHA Whaley, John Corey 2011 2005 Ship Breaker How I Live Now Call #: FIC BAC Bacigalupi, Paolo Call #: FIC ROS Rosoff, Meg Honor Book: Stolen by Lucy Christopher Honor Books: Airborn, by Kenneth Oppel; Chanda’s 2010 Secrets, by Allan Stratton; Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, by Gary D. Schmidt Going Bovine Call #: FIC BRA Bray, Libba 2004 The First Part Last Honor Books: The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Call #: FIC JOH Johnson, Angela Traitor to the Nation, Vol. -

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM Presents MACBETH by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE WITH BARZIN AKHAVAN, RAFFI BARSOUMIAN, NADIA BOWERS, N’JAMEH CAMARA, ERIK LOCHTEFELD, MARY BETH PEIL, COREY STOLL, BARBARA WALSH, ANTONIO MICHAEL WOODARD COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN ANN HOULD-WARD SOLOMON WEISBARD MATT STINE FIGHT DIRECTOR PROPS SUPERVISOR THOMAS SCHALL ALEXANDER WYLIE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN SOUND DESIGN DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI PRESS PRODUCTION CASTING REPRESENTATIVES STAGE MANAGER TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND BERNITA ROBINSON KARYN CASL, CSA ASSOCIATES ASSISTANT DESTINY LILLY STAGE MANAGER JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE MACBETH (in alphabetical order) Macduff, Captain ............................................................................ BARZIN AKHAVAN Malcolm ......................................................................................... RAFFI BARSOUMIAN Lady Macbeth ....................................................................................... NADIA BOWERS Lady Macduff, Gentlewoman ................................................... N’JAMEH CAMARA Banquo, Old Siward ......................................................................ERIK LOCHTEFELD Duncan, Old Woman .........................................................................MARY BETH PEIL Macbeth..................................................................................................... -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

Willy Loman and the "Soul of a New Machine": Technology and the Common Man Richard T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine English Faculty Scholarship English 1983 Willy Loman and the "Soul of a New Machine": Technology and the Common Man Richard T. Brucher University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/eng_facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Brucher, Richard T., "Willy Loman and the "Soul of a New Machine": Technology and the Common Man" (1983). English Faculty Scholarship. 7. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/eng_facpub/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. a Willy Loman and The Soul of New Machine: Technology and the Common Man RICHARD T. BRUCHER As Death of a Salesman opens, Willy Loman returns home "tired to the death" (p. 13).1 Lost in reveries about the beautiful countryside and the past, he's been driving off the road; and now he wants a cheese sandwich. ? But Linda's that he a new cheese suggestion try American-type "It's whipped" (p. 16) -irritates Willy: "Why do you get American when I like Swiss?" (p. 17). His anger at being contradicted unleashes an indictment of modern industrialized America : street cars. not a The is lined with There's breath of fresh air in the neighborhood. -

A Position Paper on E-Lending by the Joint Digital Content Working Group

The Need for Change: A Position Paper on E-Lending by the Joint Digital Content Working Group December 2020 Introduction COVID-19 has for months shuttered most library buildings. Libraries have been forced to operate entirely electronically. Schoolchildren and their parents have been especially disadvantaged: many and perhaps most school systems began in autumn 2020 as online only, with in-school library collections languishing unused. Public and academic libraries started slowly but safely to re-open, often for curbside service only, only to be forced to scale back by an autumn pandemic resurgence. Much concern and uncertainty about safety exists. A study of COVID-19 and library materials has suggested the virus can survive on commonly used library materials, if stacked, for at least 5 days and even longer on some materials, leading to quarantining periods, complicating circulation, and raising further concerns about personnel and public safety. Even as libraries open, users may stay away or avoid physical materials to avoid any possible virus transmission; a return to using a mix of physical and electronic materials will be slow, influenced by both public health guidelines and public opinion. While we all look forward to the end of the pandemic, we must also recognize that the pandemic will have lasting effects on society: how we live, work, learn and play. The pandemic has accelerated trends that were already happening; however, the pandemic has also introduced unforeseen new behaviors and expectations. Libraries are grappling with extraordinary demand for both digital content and services--two costly program areas--that will add to the strain on already lean budgets. -

From Rendezvous to Picket Fence: Tracing the Changing Frontier and Novelistic Development in A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 From Rendezvous to Picket Fence: Tracing the Changing Frontier and Novelistic Development in A. B. Guthrie, Jr.'s Western Pentology Raymond Charles Schmudde Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Schmudde, Raymond Charles, "From Rendezvous to Picket Fence: Tracing the Changing Frontier and Novelistic Development in A. B. Guthrie, Jr.'s Western Pentology" (1977). Masters Theses. 3330. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3330 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. 111 I Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because Date Author pdm From Rendezvous to �icket Fence : - Tracing the Changing Frontier and Novelistic Development in Jr.'s Pentology A. -

Modern First Editions & 20Th Century Literature

Modern First Editions & 20th Century Literature BUDDENBROOKS 21 Pleasant Street On the Courtyard Newburyport, MA. 01950, USA Boston MA. 02116 - By Appointment (617) 536-4433 F: (978) 358-7805 [email protected] or [email protected] www.Buddenbrooks.com (617) 536-4433 Newburyport - Boston - Mount Desert Island [email protected] The Debut Novel of Iain Banks - The Wasp Factory “One of the Top 100 Books of the 20th Century” By One of the “50 Greatest” British Writers 1 Banks, Iain. THE WASP FACTORY (London: Macmillan, 1984) First edition, first printing. The Author’s First Book. 8vo, publisher’s original brown cloth lettered in gilt, in the original dustjacket. 184 pp. A near as mint copy, the dustjacket and text block both pristine. FIRST EDITION OF THIS SCARCE WORK, THE FIRST BOOK BY THE AUTHOR. Iain Banks was named in 2008 by THE TIMES to their list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”. A 1997 poll of over 25,000 readers listed The Wasp Factory as one of the top 100 books of the 20th century. As an unknown writer, Banks’ success was a question and the print run on this debut novel was very small. Thus the difficulty in obtaining a true first printing of the book as e.her $350. Charles Bukowski in Original Wrappers Poems Written Before Jumping Out of An 8 Story Window A Scarce Limited First Edition - 1975 2 Bukowski, Charles. POEMS WRITTEN BEFORE JUMPING OUT OF AN 8 STORY WINDOW (Salt Lake City: Litmus Inc., 1975) Scarce, first edition with correspondence, second printing. -

The Story of Grace Lutheran Church 7 the Story of Grace Lutheran School 23

The History of Grace A Church Blessed for 75 Years With the Wonderful Acts of Our Gracious God Charter members of Grace Lutheran Church, back row Ruth and Bill Petzold, front Ted and Esther Rott. on March 11, 1973 nearly 40 years after they and six others signed the constitution June 14, 1933. Published by Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church and School Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin 4 Preface This book is the story of God at work, spreading His love and grace in the community of Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin. It is a story that is told by the way His faithful people have responded to the love they have learned to know through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. While it is a story that was acted out by faithful Christians, it is a story about the acts of a gracious, loving God. In this book you will find the personal stories and reflections of three Senior Pastors who were prepared and called by God to inspire and lead His flock at Grace Lutheran Church. Each was uniquely equipped by God to carry out His mission during the years he served. Each faced special challenges, and often each turned to God for the strength needed to carry on with His work. Grace Church started with a gathering of 17 families with 25 adults and six children in September 1932. Since then it has grown to over 2,300 members where weekly services often exceed 1,000 worshipers. This book documents the trials and challenges this congregation has faced, and the difficult decisions that were required to provide needed facilities and staff for a growing church and school. -

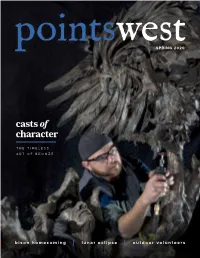

Casts of Character the Timeless Art of Bronze

pointswestSPRING 2020 casts of character the timeless art of bronze bison homecoming | lunar eclipse | outdoor volunteers DIRECTOR′S 16 NOTES Lynn Richardson helps clean Peter Fillerup’s statute Bill Cody — Hard and Fast All the PETER SEIBERT Way during its 2010 installation at the Executive Director and CEO Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Thank you all for your kind and support- ive e-mails, texts, and messages regarding the new direction for Points West. I hope that you continue to enjoy this publication as we connect people to the stories of the Ameri- can West. This past summer, our family discovered an incredible high-mountain, alpine meadow located just outside of Cody, Wyoming. My aging Trailblazer worked hard to get us to the top of several steep climbs to reach the field. When we finally got there, we could see what appeared to be more than a mile of purple lupines in full bloom. To say that it was spectacular is truly an understatement, as the field was so filled with flowers we could barely walk without stepping on them. It was a place to lie on your back, stare at the clouds, and experience everything that a Rocky Moun- tain summer day has to offer. With that in mind, as winter winds down and spring approaches, I hope you will dream of your own summer meadow high in the Rockies. A place you suspect no one has visited since Buffalo Bill. As you hold that in your mind, start making plans to come back to Cody. Spend some time here this summer. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R.