UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Expressing Ignorance With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

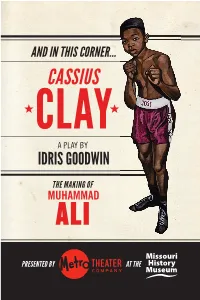

And in This Corner: Cassius Clay Playbill

AND IN THIS CORNER... CASSIUS CLAY A PLAY BY IDRIS GOODWIN THE MAKING OF MUHAMMAD ALI PRESENTED BY AT THE NEW Early Childhood Center with Organic Garden & Chickens! Unforgettable. WYDOWN-FORSYTH HISTORIC DISTRICT AGE 3 - GRADE 6 ForsythOnline.com MISSION STATEMENT Inspired by the intelligence and emotional wisdom of young people, we create professional theater, foster inclusive community, and nurture meaningful learning through the arts. BOARD OF DIRECTORS EMERITUS MEMBERS STAFF Jason McAdamis Marlene Birkman Julia Flood (President) Terry Bloomberg Artistic Director Ken Jones Robert Couch Matthew Neufeld (Vice President) Managing Director Suzanne Couch Susan W. Nall, Ph.D. Sarah Rugo Mary Ellen Finch, Ph.D. (Secretary) Production Manager Nancy Garvey John D. Weil David Blake (CFO) Camille Greenwald Technical Director David Bentzinger Marcia Kerz Karen Weberman Shaughnessy H. Daniels Daniel Jay Education Director Gary Feder Ellen Livingston John Wolbers Julia Flood* James R. Moog Resident Teaching Artist Susan Gamble Joseph M. Noelker Renita James Teaching Artist Fellow Aaron Jennings, M.S.W. Peggy O’Brien David Warren Roderick Jones, Ed.D., M.P.A. Janet Schoedinger Development Director Antonio Maldonado Mary Stigall Maria I. Straub Jan Paul Miller Anabeth C. Weil Operations Coordinator Matthew Neufeld* FOUNDERS Ron James Mark Sandvos Marketing and Zaro Weil Barbara Shuman Communications Director Lynn Rubright Amber Simpson Ph.D. Beverly Rombach Development Consultant Candice Smith Taylor Steward David Stiffler Engagement Manager Mary Tonkin Jacqueline Thompson Stephanie Tucker Community Partnerships Manager Deborah Van Ryn *ex officio, non-voting Metro Theater Company is a professional theater for young people and families and a not-for-profit 501(c)3 organi- zation. -

5713 Theme Ideas

5713 THEME IDEAS & 1573 Bulldogs, no two are the same & counting 2B part of something > U & more 2 can play that game & then... 2 good 2 b 4 gotten ? 2 good 2 forget ! 2 in one + 2 sides, same story * 2 sides to every story “ 20/20 vision # 21 and counting / 21 and older > 21 and playing with a full deck ... 24/7 1 and 2 make 12 25 old, 25 new 1 in a crowd 25 years and still soaring 1+1=2 decades 25 years of magic 10 minutes makes a difference 2010verland 10 reasons why 2013 a week at a time 10 things I Hart 2013 and ticking 10 things we knew 2013 at a time 10 times better 2013 degrees and rising 10 times more 2013 horsepower 10 times the ________ 2013 memories 12 words 2013 pieces 15 seconds of fame 2013 possibilities 17 reasons to be a Warrior 2013 reasons to howl 18 and counting 2013 ways to be a Leopard 18 and older 2 million minutes 100 plus you 20 million thoughts 100 reasons to celebrate 3D 100 years and counting Third time’s a charm 100 years in the making 3 dimensional 100 years of Bulldogs 3 is a crowd 100 years to get it right 3 of a kind 100% Dodger 3 to 1 100% genuine 3’s company 100% natural 30 years of impossible things 101 and only 360° 140 traditions CXL 4 all it’s worth 150 years of tradition 4 all to see (176) days of La Quinta 4 the last time 176 days and counting 4 way stop 180 days, no two are the same 4ming 180 days to leave your mark 40 years of colorful memories 180° The big 4-0 1,000 strong and growing XL (40) 1 Herff Jones 5713 Theme Ideas 404,830 (seconds from start to A close look A little bit more finish) A closer look A little bit of everything (except 5-star A colorful life girls) 5 ways A Comet’s journey A little bit of Sol V (as in five) A common ground A little give and take 5.4.3.2.1. -

Catalogo De Canciones 23/02/2015 15:28:34

CATALOGO DE CANCIONES 23/02/2015 15:28:34 IDIOMA: Inglés CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO IN92987 £1 FISH MAN ONE POUND FISH IN80017 101 DALMATIONS CRUELLA DE VIL IN80018 10CC DONNA IN92379 10CC DON'T TURN ME AWAY IN80019 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY IN92380 10CC FEEL THE LOVE IN92381 10CC FOOD FOR THOUGHT IN92382 10CC GOOD MORNING JUDGE IN80020 10CC I'M MANDY IN80021 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE IN92383 10CC LIFE IS A MINESTRONE IN92384 10CC ONE TWO FIVE IN92385 10CC PEOPLE IN LOVE IN92386 10CC SILLY LOVE IN80023 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE IN80024 10CC WALL STREET SHUFFLE IN92387 10CC WOMAN IN LOVE IN80025 1910 FRUITGUM CO SIMON SAYS IN80026 1927 COMPULSORY HERO IN80027 1927 IF I COULD IN89409 1927 THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU IN80028 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) IN80029 2 EVISA OH LA LA LA IN80030 2 PAC FEAT DR DRE CALIFORNIA LOVE IN80031 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT IN80032 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 21ST CENTURY GIRLS IN91367 2ND BAPTIST CHURCH (LAUREN RISE UP JAMES CAMEY) IN92842 2PAC CHANGES IN92841 2PAC DEAR MAMA IN92399 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU IN89406 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE IN90644 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE IN91291 30 SECONDS TO MARS FROM YESTERDAY IN90160 30 SECONDS TO MARS KINGS AND QUEENS IN91290 30 SECONDS TO MARS THE KILL IN93248 30 SECONDS TO MARS UP IN THE AIR (CLEAN VERSION) IN93249 30 SECONDS TO MARS UP IN THE AIR (EXPLICIT VERSION) IN91498 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY IN26754 3OH! 3 FEAT KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK IN89722 3OH!3 DON'T TRUST ME IN90099 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK Page 1 CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO IN90533 -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Mountain Chant a Navajo Ceremony.Pdf

SMITHSONIAN IXSTITtiTIOX BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY, THE MOUNTAIN CHANT: A NAVAJO CEREMONY. BY Dr. WASHINQTON MATTHEWS, U. S. A. 379 CONTENTS. Page. lutroductioii 385 Myth of the origin of dsilyJdje qajill 387 Ceremonies of dsilyfdje qafil 418 First four days 418 Fifth day 419 Sixth day .' 424 Seventh day 423 Eighth day 429 Ninth day (until sunset) 430 Last night 431 First dance (nahikM) 432 Second dance (great plumed arrow) 433 Third dance 435 Fonrth dance 436 Fifth dance (sun) 437 Sixth dance (standing arcs) 437 Seventh dance 438 Eighth dance (rising sun) 438 Ninth dance (Hoshk3.wn, or Tucca) 439 Tenth dance (bear) 441 Eleventh dance (fire) 441 Other dances 443 The great pictures of dailyldje qa^b.1 44 First picture (home of the serpents) 44R Second picture (yays and cultivated plants) 447 Third picture (long bodies) 45O Fourth picture (great plumed arrows) 451 Sacrifices of dsilyfdje qafill 451 Original texts and translations of songs, &c 455 Songs of sequence 455 First Song of the First Dancers 456 First Song of the Mountain Sheep 457 Sixth Song of the Mountain Sheep 457 Twelfth Song of the Mountain Sheep 458 First Song of the Thunder 458 Twelfth Song of the Thunder 459 First Song of the Holy Young Men, or Young Men Gods 459 Sixth Song of the Holy Young Men 460 Twelfth Song of the Holy Young Men 460 Eighth Song of the Young Women who Become Bears 461 One of the Awl Songs 461 First Song of the Exploding Stick 462 Last Song of the Exploding Stick 462 First Daylight Song 463 Last Daylight Song 463 381 382 CONTENTS. -

Account of a Journey Through Northeastern Texas

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1970 Account of a Journey Through Northeastern Texas Edward Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Smith, Edward (1970) "Account of a Journey Through Northeastern Texas," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol8/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. East, Texas Historical Journal 29 A(TOlTNT OF A JOllRNEY THROUGH NORTHEASTERN TEXAS (Editor's Note: This is the third ami final installment of an account of a trip tllrough Northeastern Texas made by Edward Smith,) NOTE: '1 rrell'W, Conn r, Jl'., imm eli, te past President of the East Texa Historical Association, is a 'oHector of Texas Maps, Among the photo copie of maps in hi, collection j a map showing the route of inspector. through NOl'lh-Eastel'l1 Texa- in 1 49, H first thought thi j.HJrticul<1l" map had been made for inspect rs of land certificates, but the map began ill Jeffer on and made a circular route, in tead of beginning Ot' returning to Austin, Then he I' alizecl that the year 1849 Was not the date of the inspec tion of L,lnd Certificates for they had been authorized by the -

Artist / Act Series Category Mentor Finishing Position

Finishing Artist / Act Series Category Mentor Nationality Region City Position Cassie Compton 1 16-24s Sharon Osbourne 5th England London London Roberta Howett 1 16-24s Sharon Osbourne 9th Ireland Dublin Tabby Callaghan 1 Under-25s Sharon Osbourne 3rd Ireland Sligo 2 to Go 1 Groups Louis Walsh 7th England Midlands Nottingham G4 1 Groups Louis Walsh 2nd England Various Voices with Soul 1 Groups Louis Walsh 6th England South Luton Steve Brookstein 1 Over 25s Simon Cowell 1st England London South London Verity Keays 1 Over 25s Simon Cowell 8th England North Grimsby Rowetta Satchell 1 Over 25s Simon Cowell 4th England North Manchester Phillip Magee 2 16-24s Louis Walsh 10th Ireland Larne Shayne Ward 2 16-24s Louis Walsh 1st England North Manchester Chenai Zinyuku 2 16-24s Louis Walsh 9th England North Bradford Nicholas Dorsett 2 16-24s Louis Walsh 7th England London Enfield 4Tune 2 Groups Simon Cowell 11th England South Various Addictiv Ladies 2 Groups Simon Cowell 12th England London The Conway Sisters 2 Groups Simon Cowell 6th Ireland Sligo Journey South 2 Groups Simon Cowell 3rd England North Middlesbrough Andy Abraham 2 Over 25s Sharon Osbourne 2nd England London North London Brenda Edwards 2 Over 25s Sharon Osbourne 4th England South Luton Maria Lawson 2 Over 25s Sharon Osbourne 8th England London London Chico Slimani 2 Over 25s Sharon Osbourne 5th Wales Wales Bridgend Nikitta Angus 3 16-14s Simon Cowell 7th Scotland Scotland Glasgow Leona Lewis 3 16-24s Simon Cowell 1st England London North London Ashley McKenzie 3 16-24s Simon Cowell -

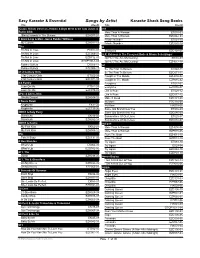

Easy Karaoke Song Book Including Essential

Easy Karaoke & Essential Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 911 Robin Gibb More Than A Woman ET015-03 (Barry) Islands In The Stream EZH077-01 More Than A Woman EZC064-03 1 Giant Leap & Maxi Jazz & Robbie Williams Private Number ET021-10 My Culture EZH011-13 Private Number EZC070-10 10cc A I'm Not In Love EK012-01 Starbucks EZC128-05 I'm Not In Love EZC006-01 A.R. Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls & Nicole Scherzinger I'm Not In Love EZSP12-01 Jai Ho! (You Are My Destiny) EKI36-09 I'm Not In Love GTOP100-4-09 Jai Ho! (You Are My Destiny) EZH077-18 Rubber Bullets EK026-17 A1 Rubber Bullets EZC009-17 Be The First To Believe ET022-11 21st Century Girls Be The First To Believe EZC071-11 21st Century Girls ET022-09 Caught In The Middle EZH008-02 21st Century Girls EZC071-09 Caught In The Middle EZP015-02 2-4 Family Everytime ET027-07 Lean On Me ET021-09 Everytime EZC076-07 Lean On Me EZC070-09 Like A Rose ET028-12 2Pac & Elton John Like A Rose EZC077-12 Ghetto Gospel EZH048-02 Make It Good EZC131-08 3 Doors Down No More EZC124-08 Kryptonite EX31-04 No More FIK015-05 Kryptonite EZC133-06 Same Old Brand New You ET036-09 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Same Old Brand New You EZC085-09 Starstrukk EKI46-05 Summertime Of Our Lives ET025-07 Starstrukk EZH082-14 Summertime Of Our Lives EZC074-07 3OH!3 & Kesha Aaliyah My First Kiss EKI52-03 More Than A Woman EZH008-06 My First Kiss EZH085-12 More Than A Woman EZP015-06 3SL Rock The Boat EZH011-10 Take It Easy EZC131-05 Rock The -

The Multiple Chromosomes of Hesperotettix and Mermiria

ALlTEOR’G ~4BSTRACTOF THlR P.4PER ISSUBD BY TEE BIBLIOGRAPHIC SERVICE JVLY 21. THE MULTIPLE CHROMOSOMES OF HESPEROTETTIX AND MER,MTRIA (ORTHOPTERA) CLARENCE E. McCLUNG Department of Zoology, University of Pennsylvania EIGHT PLATES CONTENTS I. Int,roduction......................................................... 519 11. Chromosome conditions in the genus Hesperotettix. ................... 521 1. General observations.. ........................................... 521 2. The complex of H. speciosus ..................................... 522 3. The compIex of H. pratensis.. .... ...................... Fi24 4. The complex of H. brevipennis.. .................... 5. ?he complex of H. festivus.. 6. The complex of H. viridis.. .......................... 111. Chromosome conditions in the genus Mermiria ........................ 530 IV. General considerations.. ........ 1. Chromosome numbers in th 2. Chromosome numbers in ge 3. Chromosome sizes.. ....... 4. Chromosome forms.. ...... 5. Chromosome behavior. .... 6. Chromosome distribution.. .. 7. Chromosome individuality. 8. Chromosome specificity.. .. V. Summary ............................... VI. Bibliography ......................................................... 589 I. INTRODUCTION Under the title “The chromosome complex of Orthopteran spermatocytes” (’05) I described certain unusual conditions in these cells, among them the union between the accessory chromo- some and particular euchromosomes to form multiple chromo- somes. At the time my material was limited and I was able to present only a -

FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars on 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:A.M

MEN WOMEN 1. SA Steven Adler=American rock musician=33,099=89 Sunrise Adams=Pornographic actress=37,445=226 Scott Adkins=British actor and martial Sasha Alexander=Actress=198,312=33 artist=16,924=161 Summer Altice=Fashion model and actress=35,458=239 Shahid Afridi=Cricketer=251,431=6 Susie Amy=British, Actress=38,891=220 Sergio Aguero=An Argentine professional Sue Ane+Langdon=Actress=97,053=74 association football player=25,463=108 Shiri Appleby=Actress=89,641=85 Saif Ali=Actor=17,983=153 Samaire Armstrong=American, Actress=33,728=249 Stephen Amell=Canadian, Actor=21,478=122 Sedef Avci=Turkish, Actress=75,051=113 Steven Anthony=Actor=9,368=254 …………… Steve Antin=American, Actor=7,820=292 Sunrise Avenue Shawn Ashmore=Canadian, Actor=20,767=128 Soul Asylum Skylar Astin=American, Actor=23,534=113 Sonata Arctica Steve Austin+Khan=American, Say Anything Wrestling=17,660=154 Sunshine Anderson Sean Avery=Canadian ice hockey Skunk Anansie player=21,937=118 Sammy Adams Saving Abel FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars On 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:a.m. SA,Spiro Agnew Sani ,Abacha ,Head of State ,Dictator of Nigeria, 1993-98 SA,Sri Aurobindo Shinzo ,Abe ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Japan, 2006- SA,Steve Allen 07 SA,Steve Austin Sid ,Abel ,Hockey ,Detroit Red Wings, NHL Hall of Famer SA,Stone Cold Steve Austin Spencer ,Abraham ,Politician ,US Secretary of Energy, SA,Susan Anton 2001-05 SA,Susan B. Anthony Sharon ,Acker ,Actor ,Point Blank Sam ,Adams ,Politician ,Mayor of Portland Samuel ,Adams ,Politician ,Brewer led -

Fluctuations in the Great Fisheries of Northern Europe Viewed In

CONSEIL PERMANENT INTERNATlONAL POUR 1,'EXPLORATION DE LA MER RAPPORTS ET PROCRS-VERBAUX -- VOLUME ?(X FLUCTUATIONS IN THE GREAT FISHERIES OF NORTHERN EUROPE VIEWED IN THE LIGHT OF BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH BY JOHAN HJORT WITH 3 PLrlTES EN COMMISSION CHEZ ANDR. FRED. H0ST & FILS COPENHllGUE .iVI<Il, 1!I1,1 COPPNHAGUE - IMPRIYERlR BIANCO LTJNO CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 3 Fluctuations in the yield a characteristic feature of all great fisheries ................. 3 Norwegian Cod fisheries ........................................................... 3 Norwegian herring fishery ................................................... 4 Popular attempts to explain the fluctuations ........................................ 4 The theory of migration as a cause of the fluctuations ............................... 4 Probable extent of migration essentially reduced by scientific investigation ............. 6 Investigations as to the distribution of the fish in the Norwegian Sea ................. G Principal species only found on the coastal banlrs in spawning time ................... 7 A considerable portion of the stoclr annually taken by the fishery .................... 9 Preliminary irlvestigations as to the .cod fishery in northern Norwegian waters, 1900-. l903 9 Melhods of age determination adopt.ed in the investigations .......................... l0 Representative biological or vital statistics .......................................... 10 CHAPTER I The Herring Stock in' Norwegian coastal -

Catalogo De Canciones 25/01/2021 17:57:50

CATALOGO DE CANCIONES 25/01/2021 17:57:50 IDIOMA: Inglés CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO IN280028 . IF YOU'RE GETTIN IN280004 . I'M NOT IN LOVE IN280029 . IT'S THE THING IN280014 . NO LIMITS IN280024 . WHAT'S UP IN1418006 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE IN280006 10 CC RUBBERS BULLETS IN280007 10 CC THE THING WE DO FOR LOVE IN280008 10 CC WALL STREET IN280009 101 DALMATIES CRUELLA DE VILLE IN280010 112 DANCE WHIT ME IN1094010 112 U ALREADY KNOW IN280011 1910 FRUITGUM SIMON SAYS IN1723013 1975 CHOCOLATE IN1834013 1975 SOMEBODY ELSE IN1738004 1975 THE CITY IN1899009 1975 TOO TIME TOO TIME IN493020 2 EVISA OH LA LA LA IN493021 2 PAC FEATURING DR DRE CALIFORNIA LOVE IN767008 2 STARS 2 STARS IN1041012 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME IN1177001 2 UNLIMITED HERE I GO IN1177002 2 UNLIMITED LET THE BEAT CONTROL YOUR BODY IN1427002 2 UNLIMITED MAGIC FRIEND IN1427003 2 UNLIMITED MAXIMUM OVERDRIVE IN493019 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMITS IN548001 2 UNLIMITED THE REAL THINGS IN1427004 2 UNLIMITED TRIBAL DANCE IN1039004 2 UNLIMITED TWILIGHT ZONE IN280015 21 ST CENTURY GIRLS 21 ST CENTURY GIRLS IN1081002 3 DOOR DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES IN280016 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN IN280017 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT IN280018 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WHITOUT YOU IN280019 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE IN280020 3 DOORS DOWN LET ME GO IN1098003 3 DOORS DOWN LIVE FOR TODAY IN280021 3 OF HEART ARIZONA RAIN IN280023 3 T ANYTHING IN1891017 30 SECONDS TO MARS RESCUE ME IN373012 30HL3 DON'T TRUST ME IN1098007 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME Page 1 CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO IN280022 35 L TAKE IT EASY IN1079010 38 SPECIAL