Conservation Innovation in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthony Mann, “How 'Poor Country Boys' Became Boston Brahmins: the Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-Bellum

Anthony Mann, “How ‘poor country boys’ became Boston Brahmins: The Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-bellum Massachusetts” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 31, No. 1 (Winter 2003). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj. Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 How ‘poor country boys’ became Boston Brahmins: The Rise of the Appletons and the Lawrences in Ante-bellum Massachusetts1 By Anthony Mann The promise of social mobility was a central cultural tenet of the northern American states during the nineteenth century. The stories of those who raised themselves from obscure and humble origins to positions of wealth and status, whilst retaining a sufficiency of Protestant social responsibility, were widely distributed and well received amongst a people daily experiencing the personal instabilities of the market revolution.2 Two families which represented the ideal of social mobility 1 A version of this essay was first read at the conference of the British Association for American Studies, Birmingham, and April 1997. My thanks to Colin Bonwick, Louis Billington, Martin Crawford and Phillip Taylor who have advised since then. -

Cotton Whigs and Union: the Textile Manufacturers of Massachusetts and the Coming of the Civil

././ // 518CB 18CB8B:5D'-) '-, CCB8B:HBCB. 8BH89HC889H 8B:9CBC8 4 CBBC5C82B /CCB6B D.&&:8B:B&('))&') BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUA'rE SCHO OL \ t .{I',, D ( : ( I ( Dissertation COTI'ON WillGS AND UHION: Tii--:E OF MASSA.GHIJS.E'T'l1S Al'ID THE ,GOMING OF THE CIVIL WAR . By Thomas Henry O'Connor (A.B., Boston College, 1949; A. M., Boston College, 1950) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1958 Approved by First Reader , " . ,, Professor. .of . Histor;. • • .... • • • • • • Second Reader • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Professor of Hist ory TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE Introduction. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • i I . Lords of the Loom • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 I I. Broadcloth and '.J:; otton • • • • • • • • • • • 34 III. Got ton Versus .Conscience. • • • • • • • • • • 69 I V. Gentleman's Agreement • • • • • • • • • • • • 105 v. Awake t he Sleep ing Ti ger. • • • • • • • • • • 135 VI. The Eleventh Hour • • • • • • • • • • 177 Conclusion. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 225 Bi b1iography. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 229 Abstract. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 245 Vita. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 248 INTRODUCTION In 1941J Philip FonerJ in his Business and SlaveryJ made an appeal for a more detailed study of the Northern business man and his reaction to the coming of the Civil War. Countering the popular interpretation that the war was the product of two conflicting economic systemsJ Professor Foner presented his own observations regarding the concerted efforts of the New York financial interests to Check any and all move- ments which tended to precipitate an intersectional struggle. The documented reactions of this particular group of Nor t h ern business men could not be explained in terms of an over- simplified economic interpretation of the Civil War, and for this reason Professor Foner pointed to the need for more intensive research into the economic sources and materials of the ante-bellum period. -

Lawrence Academy Area Form Survey

FORM A-AREA Assessor's Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 1l3, 114, 115, 116 17-19,143,145,149,177, 178,344,345,460 Massachusetts Historical Commission 220 Morrissey Boulevard Massachusetts Archives Building Boston, MA 02125 Town: Groton Place: Groton Center Photographs Name ofArea: Lawrence Academy X Seeconunuauonshe~ Current Use: College preparatory school Construction Dates or Period: 1782-2004 Overall Condition: Good - excellent Major Intrusions and Alterations: Multiple modem buildings, 1793 school building burned 1868; 1871 School Building burned 1956; replaced 1957 Acreage: Approximately 102 Sketch Map Recorded by: Sanford Johnson X See contiRlUltion sheet Organizatjon: Groton Historical Commission Date (MqnthlY~ar): 1/09 AREAFORM ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION: Describe architectural, structural and landscapefeatures and evaluate in terms ofother areas within the community. Introduction The campus of the Lawrence Academy at Groton, founded during a meeting of local residents in 1792 and incorporated in 1793, contains over a dozen historic buildings including three high style Federal Period residences that flanked the original schoolhouse, an 1863 Second Empire style brick dormitory, 19th century Victorian residences in use as dormitories and offices as well as school buildings from the mid 20th century. These are located primarily on the Powderhouse Road campus as well as along both sides ofthe southern part of Main Street. Playing fields extend as far east as Lovers Lane and to the west of Main Street. Landscape elements include the campus quadrangle on Powderhouse Road which is fonned by the three principal school buildings. The multiple parcels comprise approximately 100 acres and contain around 25 buildings. The original school building from 1793 (burned in 1868) and the successor from 1868 (burned 1956) faced Main Street between the 1792 Dana and 1802 Brazer Houses, the school's two oldest architectural resources. -

Selections from the Diaries of William Appleton 17861862

NO T E ‘ U R ancestor William Appleton was a succesg ul and well-known erch nt o oston It seems to me wo rthwhile m a fB . to try to picture him to his descendants by means of the diaries which he ke t o r man ears p f y y . I have tried to bring out the most salien t and in terestingparts o his l e b selections romthese diaries but I n d it im ossible f if y f , fi p to p resen t himto o thers as I myselfhave come to know himthro ugh em th . c This book tells o his visits to his mother o his visitin his f , f g sich children and riends who are sich and o his s erin f , f ufl g with them and o his kindness to the relatives o his arents , f f p an d to those of his wife; but his diaries tellof suchloving deeds over and over a ain g . c The book tells o his dinner arties and o his man riends f p , f yf who came to the ho u se; but his diaries tellof his frien ds coming and oin allthe time and muchstress is laid on the love he has g g , o r r e d f his f i n s . The booh tells o his devotion to the Church services to tho se o f , f his own articular church and to its ministers thus showin his p , , g deep appreciatio n of the SpiritualLife that they stood for ; ofhis feelings of sinfulness and the searchings ofhis own heart; but his o d over a n diaries tellof these acts and these th ughts over an ag i . -

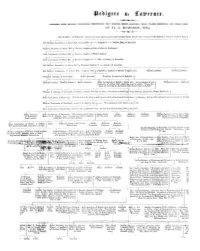

Rltlh JU!;GISTIUIS, .\II: U OTII IJ:Lt OUU,L by H

()OltlPILEO l'BOJtl l~it:lLVS' \/ ISl'l'A'l'IO!IIIS, ll'VlotUli>l'J'ION!! llOll!l'Jillf, DBEPi, t.:HAlt'l'EUIS, ,VILLI!,, l'ARltlH JU!;GISTIUIS, .\II: U OTII IJ:lt OUU,l BY H. G. SOM:ERBY, ESQ. SIR HUllEli'l' LAWREN CE: had unns (a cross ruguley, gulcs) conferred upon hindiy Richard Cwur do Lion, for his bravery m scaling the ,valls of Acre, A Srn RoJERT LAWllENCE, of .,~htou llall, in Lancashire. I --, q.aughter of -- Tl·afford, llliq., QI 1u.ucashire. JAJi:s LAWllENCE, of Ashton ][all. I Matiltl:,, ,laugh~:-aud heir of John de Washington. Jou(- LAWUENCE, of Ashton;~~!~-; i\fargaret, ,laughter of Walter Chesfonl. Jo.h· LAWHENCE, of Ashton l::1;111. I Eliz,d,cth, <laughter of -- Holt, of Stabley, in Lancashire. I --- ----,-- - Sui H0111,u, r LAWlU:NVJ<:, of A:_'_' Ifoll, I J',,farg·arot, daughter of -- Holden, of Lancashire. r- I I sui ROllEJ• r LAWRBNCB, of .\shton Hall: li.-ing in 1454. = Amphilbus, daughter of :Edward Lollgford, Esq. Thomas Lawrence. William Lawrence. I I Hir JJ1es; awrencc, of A,;:t~1:;~l~~ -~~-;:Jcrt Lawrence. NrcHlLAS LAWRENCE, of Age~Cl'oft. = I i-- .l I I Tho1,1as L:1wrence. Nteholas L1wre11ce. Robert Lawrence. JJHN LAWRENCE;; of Suffolk: diedjn 1461. In the pedigree of the= Wiltam Lawrence. Henry La Lawrcnces of Ashton H,ill, under thf. name is written, "From this I John are descended the Lawrences 01 St. James' Park, in Suffolk." -------------- THO,~AS ~'- WREN~E, ·o; l,umln,rgh, in Suffolk; made his will July 17, 1471: owned lauds in Jl.umburg 1; South Elmhani, Spettishall, ·wisset, Holton, &c. -

Abbott Lawrence in the Confidence-Man 25

abbott lawrence in the confidence-man american success or american failure? william norris "Where does any novelist pick up any character? For the most part, in town, to be sure. Every great town is a kind of man-show, where the novelist goes for his stock, just as the agriculturist goes to the cattle-show for his."1 So the narrator of Herman Melville's The Confidence-Man candidly observes in an interpolated chapter distinct from the narrative itself. There is little need to be leery of accepting such a statement as a part of Melville's artistic credo, for we know how heavily he draws on characters from life. In this novel he unquestionably shanghais Emerson, Poe, and the "original confidence man" (a canny operator probably named William Thompson) aboard the steamship Fidèle, and many scholars have made cases for his having relied upon a host of other figures.2 I wish to identify yet another character, the "gentleman with gold sleeve-buttons" of Chapter 7: I believe he is based on Abbott Law rence, an eminent merchant-statesman-philanthropist of the period. Yet Melville's use of Lawrence and other contemporaries as char acter models illustrates much more than a habit of composition. Their function, however, is not simply to act out roles in a story in the tradi tional sense of fiction; in this novel, they serve to reflect Melville's consciousness of his period's social issues and problems, and his continual concern with ambiguities inherent in the total fabric of American life and the American experience. -

The Irony of Urban School Reform, Ideology and Style in Mid-Nineteenth Century Massachusetts. Final Report

r R E P O R T RESUMES ED 015 522 24 EA 000 826 THE IRONY OF URBAN SCHOOL REFORM,IDEOLOGY AND STYLE IN MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS. FIIALREPORT. BY- KATZ, MICHAEL B. REPORT NUMBER CRF-S-085 PUB DATE 66 REPORT NUMBER BR-5-8183 . EDRS PRICE MF-$1.50 HC-$15.76 392F. DESCRIPTORS- *EDUCATIONAL CHANGE, *URBANEDUCATION, ECONOMIC FACTORS, INDUSTRIALIZATION,MOTIVATION, PUBLIC EDUCATION, HIGH SCHOOLS, *EDUCATIONAL INNOVATION,COMMUNITY LEADERS, SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS, *RURAL URBANDIFFERENCES, ADMINISTRATIVE PERSONNEL, EDUCATIONALOBJECTIVES, DELINQUENT REHABILITATION, CORRECTIONAL EDUCATION,FACTOR ANALYSIS, SCHOOL COMMUNITY RELATIONSHIP,*HISTORICAL REVIEWS, CAMBRIDGE, THE ORIGINS OF MASS POPULAR EDUCATIONIN NINETEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS ARE STUDIEDIN TERMS OF THE RELATION BETWEEN REFORMER IDEOLOGY ANDSTYLE OF REFORM WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF FUNDAMENTAL ALTERATIONSIN THE LIFE CONDITIONS IN MASSACHUSETTS. THREE SIGNIFICANTEVENTS ARE ANALYZED IN DETAIL--(1) ABOLITION OF BEVERLY HIGHSCHOOL IN 1860, (2) ATTACK OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTEOF INSTRUZTION ON CYRUS PEIRCE, AND (3) CRITICISM OF THESTATE REFORM SCHOOL OFFERED BY SOME OF THE STATE'S LEADINGREFORMERS. THE STUDY CONCLUDES THAT EDUCATIONAL REFORM WASSPONSORED FY A COALITION OF THE SOCIAL AND FINANCIAL LEADERS OFMASSACHUSETTS: MIDDLE CLASS PARENTS, AND EDUCATORS. A FACTORANALYSIS OF RELEVANT VARIABLES IN THE HISTORICAL STUDY ISAPPENDED. (HM) Aililli. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION &WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCEDEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATINGIT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENTOFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. THE IRONY OF URBANSCHOOL REFORM, Ideology and Style inMid-NineteenthCenturyMassachusetts by Michael B. Katz UnitedStates Office of Education, Cooperative Research Program, Project S-085 Final Report 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACUPWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS Educational Reform:The Cloud of Sentiment INTRODUCTION. -

The Academy Journal

The A cademy Journal Lawrence Academ y/Fall 2014 An Engaged Community Working Toward Mastery Trustees of Lawrence Trustees with 25 or More Academy Years of Service Editorial Team Bruce M. MacNeil ’70, President 1793–1827 Rev. Daniel Chaplin John Bishop Lucy C. Abisalih ’76, Vice President 1793–1820 Rev. Phineas Whitney Director of Communications Geoffrey P. Clear, Treasurer 1793–1825 Rev. John Bullard Dale Cunningham Gordon Sewall ’67, Secretary 1794–1827 Samuel Lawrence Assistant Director of Communications 1795–1823 James Brazer Bev Rodrigues Jay R. Ackerman ’85 1801–1830 Rev. David Palmer Communications Publicist Kevin A. Anderson ’82 1805–1835 Jonas Parker Layout/Design/Production Ronald M. Ansin 1807–1836 Caleb Butler Dale Cunningham Timothy M. Armstrong ’89 1811–1839 Luther Lawrence Assistant Director of Communications Deborah Barnes 1825–1854 Rev. George Fisher Robert M. Barsamian ’78 1830–1866 Jonathan S. Adams Editorial Council Barbara Anderson Brammer ’75 1831–1860 Nehemiah Cutter Amanda Doyle-Bouvier ’98 Jennifer Shapiro Chisholm ’82 1831–1867 Joshua Green Academy Events Coordinator Patrick C. Cunningham ’91 1835–1884 Rev. Leonard Luce Sandy Sweeney Gallo ’75 Judi N. Cyr ’82 1849–1883 Agijah Edwin Hildreth Director of Alumni Relations Christopher Davey 1863–1896 William Adams Richardson Geoff Harlan Director of Annual Giving Gregory Foster 1865–1893 Amasa Norcross Catherine Frissora 1866–1918 Samuel A. Green Hellie Swartwood Director of Parent Programs Bradford Hobbs ’82 1868–1896 Miles Spaulding Susan Hughes Audrey McNiff ’76 1871–1930 Rev. William J. Batt Assistant to the Head of School Peter C. Myette 1875–1922 George Samuel Gates Rob Moore Michael Salm 1876–1914 James Lawrence Assistant Head of School David Santeusanio 1890–1933 George Augustus Sanderson Dan Scheibe David M. -

A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), Unabridged and Unrevised Charles Breunig

Lawrence University Lux Selections from the Archives University Archives 1994 "A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), unabridged and unrevised Charles Breunig Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/archives_selections Part of the United States History Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Breunig, Charles, ""A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964), unabridged and unrevised" (1994). Selections from the Archives. 7. https://lux.lawrence.edu/archives_selections/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selections from the Archives by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "A GREAT AND GOOD WORK": A HISTORY OF LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY (1847-1964) by Charles Breunig Unabridged and Unrevised Version Appleton, Wisconsin 1994 INTRODUCTORY NOTE This manuscript is an unabridged and unrevised version of the book published by the Lawrence University Press in 1994 with the title "A Great and Good Work": A History of Lawrence University (1847-1964). It contains in many places more detail than what appears in the published work. It is organized somewhat differently from the published version with separate chapters on the conservatory of music, the trustees, and athletics. Some, though not all, of the material from these chapters is integrated into the narrative of the published history. An expanded table of contents listing sub-sections within each chapter will enable readers to turn to topics in which they may be particularly interested. -

Liberty Before Union : Massachusetts and the Coming of the Civil War

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 Liberty before union : Massachusetts and the coming of the Civil War. Stuart John Davis University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Davis, Stuart John, "Liberty before union : Massachusetts and the coming of the Civil War." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1342. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1342 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIBERTY BEFORE UNION: MASSACHUSETTS AND THE COMING OF THE CIVIL WAR A Dissertation Presented By STUART JOHN DAVIS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July 1975 Hi s tory (c) Stuart John Davis All Rights Reserved LIBERTY BEFORE UNION: MASSACHUSETTS AND THE COMING OF THE CIVIL WAR A Dissertation Presented By STUART JOHN DAVIS Approved as to style and content by: Bruce Laurie, Member Sidney Kaplan, Member Gerald W. Mc Far land, Chairman Department of History July 1975 Liberty Before Union: Massachusetts and the Civil War (July 1975) Stuart John Davis, A.B., Brown University M.A., University of Massachusetts Directed by: Stephen B. Oates In the years before the Civil War, Massachusetts underwent a great social and economic transformation. Agriculture declined as a source of state income and rural areas lost population. -

Amos Lawrence

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR Amos Lawrence and his son Amos Adams Lawrence provided the large bulk of the investment capital needed by Eli Thayer’s New England Emigrant Aid Company for the purchase land in the new territory then well known as “Bleeding Kansas,” needed in order to encourage the right sort of black-despising poor white Americans to settle there as “decent antislavery” homesteaders. The idea was to send entire communities in one fell swoop, increasing the value of the properties owned by this company. If political control over this territory could be achieved, they would be able to set up a real Aryan Nation, from which slaves would of course be excluded because they were enslaved, and from which free blacks Americans would of course be excluded because as human material they were indelibly inferior. HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR THOSE INVOLVED, ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY SECRET “SIX” Person’s Name On Raid? Shot Dead? Hanged? His Function Age Race Charles Francis Adams, Sr. No No No Finance white Charles Francis Adams, Sr. subscribed to the racist agenda of Eli Thayer’s and Amos Lawrence’s New England Emigrant Aid Company, for the creation of an Aryan Nation in the territory then well known as “Bleeding Kansas,” to the tune of $25,000. Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson Yes Yes Captain or Lt. 26 white Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, one of Captain Brown’s lieutenants, was born April 17, 1833, in Indiana, the son of John Anderson. -

IN 1825, John Farmer, Whom Some Have Touted As

Lineage as Capital: Genealogy in Antebellum New England francesca morgan N 1825, John Farmer, whom some have touted as “the I father of American genealogy,” encouraged his friend Joseph Willard to compose his own “family sketches.” Willard declined. He condemned his extended family as a “degenerate race.” “I have no inclination & feel no necessity to acknowledge kith or kin with any of them,” he explained. “Paul W[illard] is of this clan, a man who has [received] an education & is a sort of higher intelligence amongst them—but he is to me an exceedingly disagreeable man, and I hope you will not pump him in genealogy.” Farmer, who usually celebrated the un- earthing of colonial lineages, reassured Willard that he should feel no compulsion to “acknowledge kith or kin with” family members he disdained. “I did not know,” Farmer wrote, “that the descendants of so worthy an ancestor [as Major Simon Willard] had degenerated. But this need not discourage you, as it is probable they do not know their honorable descent.” If they did not, Farmer implied, those undesirable kin could eas- ily be ignored. Worthless lineages should in no way dissuade For their help with this article, I wish to thank Sven Beckert, Nancy Isenberg, Susan J. Pearson, Linda Smith Rhoads, Charles R. Steinwedel, Karin A. Wulf, the unnamed reader for the New England Quarterly, and, for a grant in 2006–7, the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. This article also benefits from audience questions at brown-bag lunches in 2006 at the Massachusetts Historical Society and the New Hampshire Historical Society as well as at the 2007 meeting of the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic, Worcester, Mass.