Changing Lanes Under British Command

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wir Bilden Aus!

WIR BILDEN AUS! Mit Gottfried Schultz starten Sie aus der ersten Reihe. www.gottfried-schultz.de IHRE AUSBILDUNG BEI GOTTFRIED SCHULTZ Jetzt durchstarten – legen Sie den Grundstein Ihrer beruflichen Zukunft bei uns! Sie begeistern sich für moderne Automobile, arbeiten gerne im Team, sind technikbegeistert und bereit, etwas zu leisten? Dann starten Sie Ihre Karriere bei uns, mit einer Ausbildung im kaufmännischen oder technischen Bereich. Wir bieten Ihnen die Chance auf eine erstklassige Ausbildung und einen optimalen Start ins Berufsleben. WIR BILDEN FOLGENDE BERUFE AUS » Automobilkaufmann/-frau » Fachkraft für Lagerlogistik » Kraftfahrzeug-Mechatroniker/-in • Personenkraftwagentechnik • System- und Hochvolttechnik • Karosserietechnik » Fahrzeuglackierer/-in Auf den nachfolgenden Seiten finden Sie alle Informatio- nen rund um die Ausbildungsberufe, Anforderungen und Ihre Bewerbung. Wenn Fragen offen bleiben, erreichen Sie unsere Personalabteilung unter der Tel. 02102 / 434-426. WIR FREUEN UNS AUF IHRE BEWERBUNG AUTOMOBILKAUFMANN/-FRAU (auch als Duales Studium, Abschluss Bachelor of Arts) Automobilkaufleute kennen den Automobilmarkt, die Produkte und natürlich ihr Autohaus ganz genau. VORAUSSETZUNGEN » Leidenschaft für Automobile, Engagement und hohe Motivation » Kontaktfreudigkeit und Organisationstalent » (Fach-) Abitur AUSBILDUNGSINHALTE » Überblick über die Arbeitsweisen und Prozesse im Vertrieb, im Servicebereich sowie im Teiledienst » Koordination und Steuerung von bürowirtschaftlichen Abläufen im Betrieb » Kostenrechnung und Kalkulationen -

Landkreis Holzminden Bezirk Hannover

Landkreis Holzminden Bezirk Hannover Übersicht und Gebietsentwicklung die Enklave Bodenwerder (ehemals Landkreis Hameln-Pyrmont) er- weitert. Durch die niedersächsischen Verwaltungs- und Gebietsrefor- Das Gebiet des Landkreises Holzminden erstreckt sich im Weser- men der 1970er-Jahre fielen die Gemeinden Delligsen, Lauenförde, und Leinebergland von der Landesgrenze zu Nordrhein-Westfalen Polle, Vahlbruch, Brevörde und Heinsen sowie die ehemaligen Ge- (Nachbarkreise sind Höxter und Lippe) über rund 40 km nach Osten meinden Silberborn und Meiborssen und vorübergehend auch die bis an das Leinetal (Landkreis Hildesheim) und vom Ith (Landkreis Samtgemeinde Duingen an den Landkreis Holzminden. Demgegen- Hameln-Pyrmont) über etwa 47 km nach Süden bis in den Solling über gingen die Gemeinden Brunkensen und Lütgenholzen im Aus- (Landkreis Northeim) und berührt das Bundesland Hessen (Landkreis tausch an den Altkreis Alfeld (seit 1977 Landkreis Hildesheim), wäh- Kassel). Holzminden ist mit einer Flächengröße von 692 km2 und rend die Gemeinden der Ithbörde, Bisperode, Harderode und Bes- 78 683 Einwohnern (31.12.2004) der drittkleinste Landkreis in Nieder- singen, an den Landkreis Hameln-Pyrmont kamen. 1981 wurde der sachsen. Weniger Bewohner haben nur noch die Kreise Wittmund Gebietsstand des Landkreises durch die Umgliederung der Samtge- und Lüchow-Dannenberg. Auch mit einer Bevölkerungsdichte von meinde Duingen an den Nachbarkreis Hildesheim abermals geändert. 113 Einw./km2 liegt der Landkreis Holzminden unter dem Landes- 2 durchschnitt von 168 Einw./km . Naturräume Das enge und windungsreiche Wesertal, von historischen Grenzen Naturräumlich ist das Kreisgebiet ein Teil der Mittelgebirgsschwelle, durchzogen, erschwert seit jeher die überregionale Verkehrsanbin- die aus unterschiedlichen erdmittelalterlichen Festgesteinsschollen dung der Region an die Oberzentren Hannover, Hildesheim, Göttin- besteht. -

The Volkswagen Beetle – a Success Story

The Volkswagen Beetle – A Success Story Table of Contents Page Feature – Beetle melancholy 1. Volkswagen Beetle – the sound, the humor, the smell, the feel, the l`mdtudq`ahkhsx, the image 2 VW Beetle, the real miracle 2. How it all began 6 3. Success story without end 7 4. VW Beetle ...and runs and swims and flies 11 5. Volkswagen – an international partner 14 VW Beetle through the years 6. Engine technology 16 7. Design and equipment 18 VW Beetle - Facts and figures 8. Chronology 22 9. Global production 26 10. Production locations 28 11. Sales figures by markets 29 12. Price development in Germany 30 Volkswagen Beetle – the sound, the humor, the smell, the feel, the maneuverability, the image The Sound. The typical sound of a Beetle. People of the Beetle Generation sit up and take notice when they hear it today. They are strangely touched, experience melancholy, as though remembering something long since lost. It is a sound as unmistakable as the Beetle's silhouette: it buzzes, it putters - all against a background of soothing fan noises – a feeling of euphoria which has underscored our mobility for decades and which was the accompaniment for our independence and for growing prosperity during those years. Beginning in the late 1940's and continuing into the early 1980's, the unmistakable noise of the Beetle left its mark on the sound backdrop of German streets. And in other places, as well, the air-cooled Beetle Boxer was the lead instrument in the noisy traffic concert. This is why Volkswagen advertising from the Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) agency at the end of the 1960's, advertising that is already legendary today, was titled „What the world loves about Germany"; it included a colorfully mixed collection of pictures: Heidelberg, a cuckoo clock, sauerkraut with dumplings, Goethe, a dachshund, the Lorelei – and a Beetle. -

News Release

Press Information THE BEETLE Introduction background 2 summary 3 production 5 Design objectives and exterior 6 interior 7 climate control 8 Engines 1.2-litre TSI 105 PS 9 1.4-litre TSI 150 PS 9 2.0-litre TDI 110 PS 10 2.0-litre TDI 150 PS 10 BlueMotion Technology 10 gearboxes 11 servicing 12 Running gear front and rear axle 13 electro-mechanical power steering 13 braking system, inc. ESP, HBA and XDS 13 hill hold function 13 Equipment highlights Beetle 14 Design and R-Line 15 Dune 16 Factory-fit options keyless entry 19 and technical highlights light and sight pack 19 bi-xenon headlights 20 parking sensors 20 Fender premium soundpack 20 telephone preparation 20 satellite navigation systems 20 Safety and security features 21 Euro NCAP test results 21 line-up with insurance groups 22 Warranties information 23 History original Beetle, 1938-2003 24 New Beetle, 1991-2011 27 Beetle, 2011- current 29 After hours telephone: Volkswagen Press and Public Relations Telephone 01908 601187 Mike Orford 07467 442062 Volkswagen (UK) www.vwpress.co.uk Scott Fisher 07554 773869 Yeomans Drive James Bolton 07889 292821 Blakelands Nicki Divey 07802 248310 Milton Keynes MK14 5AN Press Information THE BEETLE Volkswagen unveiled the latest generation Beetle in Shanghai on the eve of the city’s motor show in April 2011, marking a new era in this iconic car’s history. When the original was launched in 1938, it was known simply as ‘the Volkswagen’, quickly acquiring a raft of nicknames from across the world. Whatever the name, its popularity is not in question, with 21.5 million sold over 73 years. -

NORD/LB Group Annual Report 2009

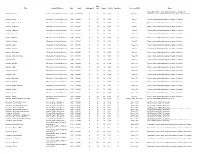

Die norddeutsche Art. Stability – the best link to the future Annual Report 2009 NORD/LB Annual Report 2009 Erweiterter Konzernvorstand (extended Group Managing Board) left to right: Dr. Johannes-Jörg Riegler, Harry Rosenbaum, Dr. Jürgen Allerkamp, Dr. Gunter Dunkel, Christoph Schulz, Dr. Stephan-Andreas Kaulvers, Dr. Hinrich Holm, Eckhard Forst These are our figures 1 Jan.–31 Dec. 1 Jan.–31 Dec. Change 2009 2008 (in %) In € million Net interest income 1,366 1,462 – 7 Loan loss provisions – 1,042 – 266 > 100 Net commission income 177 180 – 2 ProÞ t/loss from Þ nancial instruments at fair value through proÞ t or loss including hedge accounting 589 – 308 > 100 Other operating proÞ t/loss 144 96 50 Administrative expenses 986 898 10 ProÞ t/loss from Þ nancial assets – 140 – 250 44 ProÞ t/loss from investments accounted – 200 6 > 100 for using the equity method Earnings before taxes – 92 22 > 100 Income taxes 49 – 129 > 100 Consolidated proÞ t – 141 151 > 100 Key Þ gures in % Cost-Income-Ratio (CIR) 47.5 62.5 Return on Equity (RoE) – 2.7 – 31 Dec. 31 Dec. Change 2009 2008 (in %) Balance Þ gures in € million Total assets 238,688 244,329 – 2 Customer deposits 61,306 61,998 – 1 Customer loans 112,083 112,172 – Equity 5,842 5,695 3 Regulatory key Þ gures (acc. to BIZ) Core capital in € million 8,051 7,235 11 Regulatory equity in € million 8,976 8,999 – Risk-weighted assets in € million 92,575 89,825 3 BIZ total capital ratio in % 9.7 10.0 BIZ core capital ratio in % 8.7 8.1 NORD/LB ratings (long-term / short-term / individual) Moody’s Aa2 / P-1 / C – Standard & Poor’s A– / A-2 / – Fitch Ratings A / F1 / C / D Our holdings Our subsidiaries and holding companies are an important element of our corporate strategy. -

The Economics of East and West German Cars

The Economics of East and West German Cars Free Market and Command economies produce and distribute goods & services using vastly different methods. Prior to reading the documents, consider the following: a. What is the significance of car production for individuals and society? b. What is the significance of car ownership for individuals and society? c. How are cars distributed in society? In other words, who makes decisions about pricing and allocation of this good within society? Review and annotate the documents. Consider each document for its purpose, context, point of view and potential audience. What clues do the documents provide about life in East and West Germany, Cold War economic systems, and current economic issues? Use the documents to evaluate the outcomes associated with command and free market economies. Your response should include... ● A clear, well-stated claim/argument in response to the prompt. ● At least two well-developed body paragraphs in support of your claim. ● Analysis of at least seven documents to support your argument. West: Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) East: German Democratic Republic (GDR) 1 Document 1: “How German cars beat British motors - and kept going.” BBC August, 2013 In August 1945 the British Army sent a major called Ivan Hirst to take control of the giant Volkswagen plant in Wolfsburg, which had been built under the Nazis to produce 'people's cars' for the German masses. Ignoring his sceptical superiors, Hirst could see the potential amid the shattered debris of the Wolfsburg factory. Rebuilding Volkswagen, he thought, would be a step towards rehabilitating Germany as a prosperous, peaceful European ally. -

Wegweiser Psychische Gesundheit 2020

B Der Landkreis Hameln-Pyrmont möchte Sie gerne unterstützen, passende Hilfsangebote vor Ort einfach und schnell zu finden. Im Wegweiser psychische Gesundheit sind Unterstützungsangebote rund um die Themen psychische Gesundheit und psychosoziale Hilfen in verschiedenen Lebenslagen aufgeführt. Die Überschriften der Kapitel zeigen die einzelnen Themen. Darunter sind die Adressen aufgelistet, wo Sie die Angebote finden. Fast alle Angebote sind hier im Landkreis Hameln-Pyrmont. Sprechen Sie uns gerne an, wenn Sie Fragen haben. Sie erreichen uns unter 05151 / 903 – 5109 oder E-Mail: [email protected]. The district of hameln-pyrmont would like to support you in finding suitable help offers quickly and easily. The mental health guide „Wegweiser psychische Gesundheit“ contains support offers related to the topics of mental health and psychosocial help in various situations. The headings of the chapters show the individual topics, including addresses where you can find help. Almost all offers are in the district of hameln-pyrmont area. Please contact us if you have any questions. You can reach us at 05151/903-5109 or email: [email protected]. Hameln-Pyrmont ilçesi sizi bölgede, uygun yardım tekliflerini hızlı ve kolay bir şekilde bulmada desteklemek istiyor. Akıl sağlığı rehberinde, destek hizmetleri, zihinsel sağlığın ve psikososyal yardımlarının tüm konuları farklı yaşam durumlarda listelenmiştir. Bölümlerin başlıkları bireysel konuları gösterir. Tekliflerin nerede bulunduğunu gösteren adresler aşağıda listelenmiştir. Hemen hemen tüm teklifler burada Hameln-Pyrmont ilçesindedir. Herhangi bir sorunuz varsa, bize 05151/903-5109 telefon numarasından veya E-Mail: [email protected] adresinden ulaşabilirsiniz. Район Хамельн-Пирмонт хочет поддержать Вас в поиске подходящей помощи на месте. -

Bekanntmachung Über Die Zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge Für Die Wahl Des Kreistages Im Landkreis Holzminden Am 12.09.2021 Hat

Bekanntmachung über die zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge Für die Wahl des Kreistages im Landkreis Holzminden am 12.09.2021 hat der Kreiswahlausschuss in seiner Sitzung am 30.07.2021 folgende Wahlvorschläge zugelassen: A. Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl in den Wahlbereichen Bewerber/innen im Kreiswahlbereich I: Samtgemeinde Bodenwerder-Polle, Samtgemeinde Bevern (1) Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) 1 Rode, Sebastian Landtagsangestellter *1986 Hehlen 2 Lages, Friedel Rentner *1956 Bodenwerder 3 Stock, Harald Samtgemeindebürgermeister a. *1959 Bevern D. 4 Perdacher, Elke Rentnerin *1958 Bodenwerder 5 Brennecke, Wilhelm Dipl.-Ing. / Architekt *1948 Kirchbrak 6 Hoch, Winfried Rentner *1955 Brevörde 7 Weinberg, Holger Rentner *1958 Golmbach 8 Warnecke, Stefan Schlosser *1969 Halle 9 Hansmann, Rudolf Maschinenbaumeister *1948 Bodenwerder 10 Strecker, Maik Hausmann *1966 Bodenwerder (2) Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands in Niedersachsen (CDU) 1 Warnecke, Tanya Samtgemeindebürgermeisterin *1975 Bodenwerder 2 Oerke, Birgit Techn.-kaufm. Angestellte *1967 Ottenstein 3 Blume, Wolfgang Industriekaufmann i. R. *1953 Holenberg 4 Munzel, Axel Dipl.-Ing. agr. (FH) *1962 Bremke 5 Schmidt, Friedrich-Wilhelm Bankkaufmann i. R. *1954 Bodenwerder 6 Minasch, Carsten Polizeihauptkommissar *1987 Bodenwerder 7 Sudhof-Werner, Martina Kirchenmusikerin *1962 Bodenwerder 8 Zieseniß, Michael Selbst. EDV-Organisationsbera- *1967 Heyen ter 9 Samse, Gisbert Staatl. gepr. Techniker / *1962 Kirchbrak Geschäftsführer 10 Böhle, Oliver Fachgesundheits- und Kranken- -

The New Golf Celebrates Its World Premiere

ALL ABOUT VOLKSWAGEN – THE EMPLOYEE MAGAZINE FOR OUR LOCATION | OCTOBER 2019 360WOLFSBURG° ID.31 – Series Ready for Launch The countdown is on: Series production of the ID.3, the first fully electric Volkswagen from the new ID. family, will begin at the Zwickau plant in early November. The conversions are running on schedule, with employees now assembling the last few robots. Some 8,000 members of staff have been working for months at the Saxony location to get ready to meet the electric age. This has seen them involved in measures such as high-voltage training courses to learn how to handle battery systems safely. → PAGE 21 The New Golf Celebrates Its World Premiere Comic Series Presentation in Wolfsburg: eighth generation even more digital and networked than ever before on Integrity 13 short stories clarify behavioral anchors in an easy-to-understand way. → PAGE 11 f any car can be other model has shaped called a bestseller, it’s our brand quite so power- I certainly the Golf. fully and permanently over Developed and honed the decades. It is synony- from generation to gen- mous with the Volkswagen eration, it has become name and everything a global constant. The Volkswagen stands for Volkswagen brand now around the world.” celebrates the world More than 35 million China: V-Space premiere of the eighth Ralf Brandstätter, Golf models have rolled generation Golf on the Chief Operating o the production line Opens evening of October 24. Officer (COO) over the past 45 years. The V-Space has now launched in The new Golf will be and Member of strengths of the Golf – and Beijing as the new headquarters of the Board at showcased in the Hafen what has made it a world- Volkswagen Group China. -

Gasbeschaffenheit an Ausspeisepunkten Des Netzes Der Westfalen Weser Netz Gmbh

Gasbeschaffenheit an Ausspeisepunkten des Netzes der Westfalen Weser Netz GmbH Ort/Gemeinde/Samtgemeinde Ortsteil Gasqualität Aerzen Aerzen L-Gas Aerzen Groß Berkel L-Gas Aerzen Reher L-Gas Aerzen Herkendorf L-Gas Altenbeken Altenbeken H-Gas Altenbeken Buke H-Gas Altenbeken Schwaney H-Gas Bad Lippspringe Bad Lippspringe L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Bad Nenndorf L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Haste L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Helsinghausen L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Hohnhorst L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Horsten L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Kreuzriehe L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Nordbruch L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Rehren L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Rehrwiehe L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Riehe L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Riepen L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Waltringhausen L-Gas Bad Nenndorf Wilhelmsdorf L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Haaren L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Bleiwäsche L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Fürstenberg L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Leiberg L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Helmern L-Gas Bad Wünnenberg Bad Wünnenberg L-Gas Bevern Bevern L-Gas Bodenwerder Bodenwerder L-Gas Bodenwerder Daspe L-Gas Bodenwerder Halle L-Gas Bodenwerder Hehlen L-Gas Bodenwerder Kemnade L-Gas Bodenwerder Linse L-Gas Boffzen Boffzen L-Gas Boffzen Fürstenberg L-Gas Borchen Alfen L-Gas Borchen Dörenhagen L-Gas Borchen Etteln L-Gas Borchen Kirchborchen L-Gas Gasbeschaffenheit an Ausspeisepunkten des Netzes der Westfalen Weser Netz GmbH Ort/Gemeinde/Samtgemeinde Ortsteil Gasqualität Borchen Nordborchen L-Gas Büren Wewelsburg L-Gas Büren Ahden L-Gas Büren Brenken L-Gas Büren Büren L-Gas Büren Steinhausen L-Gas Coppenbrügge Coppenbrügge L-Gas Coppenbrügge Dörpe L-Gas Coppenbrügge Marienau L-Gas Delbrück Boke L-Gas -

Detaillierte Karte (PDF, 4,0 MB, Nicht

Neuwerk (zu Hamburg) Niedersachsen NORDSEE Schleswig-Holstein Organisation der ordentlichen Gerichte Balje Krummen- Flecken deich Freiburg Nordseebad Nordkehdingen (Elbe) Wangerooge CUXHAVEN OTTERNDORF Belum Spiekeroog Flecken und Staatsanwaltschaften Neuhaus Oederquart Langeoog (Oste) Cadenberge Minsener Oog Neuen- kirchen Oster- Wisch- Nordleda bruch Baltrum hafen NORDERNEY Bülkau Oberndorf Stand: 1. Juli 2017 Mellum Land Hadeln Wurster Nordseeküste Ihlienworth Wingst Osten Inselgemeinde Wanna Juist Drochtersen Odis- Hemmoor Neuharlingersiel heim HEMMOOR Großenwörden Steinau Hager- Werdum ESENS Stinstedt marsch Dornum Mittelsten- Memmert Wangerland Engelschoff Esens ahe Holtgast Hansestadt Stedesdorf BORKUM GEESTLAND Lamstedt Hechthausen STADE Flecken Börde Lamstedt Utarp Himmel- Hage Ochtersum Burweg pforten Hammah Moorweg Lütets- Hage Schwein- Lütje Hörn burg Berum- dorf Nenn- Wittmund Kranen-Oldendorf-Himmelpforten Hollern- bur NORDEN dorf Holtriem Dunum burg Düden- Twielenfleth Großheide Armstorf Hollnseth büttel Halbemond Wester- Neu- WITTMUND WILHELMS- Oldendorf Grünen- Blomberg holt schoo (Stade) Stade Stein-deich Fries- Bremer- kirchen Evers- HAVEN Cuxhaven Heinbockel Agathen- Leezdorf Estorf Hamburg Mecklenburg-Vorpommern meer JEVER (Stade) burg Lühe Osteel Alfstedt Mitteln- zum Landkreis Leer Butjadingen haven (Geestequelle) Guder- kirchen Flecken Rechts- hand- Marienhafe SCHORTENS upweg Schiffdorf Dollern viertel (zu Bremen) Ebersdorf Neuen- Brookmerland AURICH Fredenbeck Horneburg kirchen Jork Deinste (Lühe) Upgant- (Ostfriesland) -

Um-Maps---G.Pdf

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Case Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Topography, towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gabon - Libreville Service Géographique de L'Armée 1935 1:1,000,000 N 35 10 G1-A F One sheet Cameroon, Gabon, all of Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé & Principe Gambia - Jinnak Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 1 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - N'Dungu Kebbe Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 2 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - No Kunda Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 4 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Farafenni Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 5 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kau-Ur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Bulgurk Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kudang Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Fass Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kuntaur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 8 Towns, roads, political