Origins of the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts by Rick Newby and Chere Jiusto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

The MSU Ceramics Program Story

Montana State University Ceramics Program Story By Josh DeWeese, 2012 The ceramics program at Montana State University started with Frances Senska around 1945. Senska had studied with the German potter Marguerite Wildenhain and brought a Bauhaus aesthetic and sense of design to the small college in Montana after WWII. In the early days the department of MSC (Montana State College) was principally made up of Frances Senska, Jessie Wilbur, and Cyrus Conrad. Frances Senska working in her studio They hired Robert DeWeese in 1949. Peter Voulkos and Rudy and Lela Autio were in school from 1947‐51, and both Pete and Rudy developed an interest in ceramics. Senska nurtured that interest, and in the summer of 1951 she introduced them to Archie Bray who hired them to work and develop the Pottery in the brickyard. Senska taught up until the early 70s, firmly establishing the department, and designing the ceramics studio in Haynes Hall, which is still in use today. After her retirement, Jim Barnaby was hired to teach and taught for several years. In the early 1970’s Michael Peed and Rick Pope were hired and both taught until 2008, when they both retired. Their students include Frank Whitney, Ken Kohoutek, Louis Katz, Gail Busch, Tip Toland, Silvie Granatelli, and many others over a 30+ year career. Josh DeWeese, (Robert’s son) was hired in 2008, to work with Dean Adams to develop the program. Adams moved to the Foundations position in 2010, and Jeremy Hatch was hired to teach ceramic sculpture in 2011. Peter Voulkos in 1940’s Today, the program is focused on delivering a well‐ rounded education in the ceramic arts, introducing a broad range of technical skills balanced with critical evaluation and a strong awareness of contemporary issues relevant to the medium. -

Ceramics Monthly Mar05 Cei03

www.ceramicsmonthly.org Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 895-4213 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Ren£e Fairchild assistant editor Jennifer Poellot publisher Rich Guerrein Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] (614) 794-5809 fax: (614) 891-8960 [email protected] (614) 794-5866 advertising manager Steve Hecker advertising services Debbie Plummer Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (614) 794-5890 [email protected] marketing manager Susan Enderle Design/Production design Paula John graphics David Houghton Editorial, advertising and circulation offices 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio 43081 USA Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle Dick Lehman Don Pilcher Bernie Pucker Tom Turner Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by The American Ceramic Society, 735 Ceramic Place, Westerville, Ohio 43081; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the editors or The Ameri can Ceramic Society. subscription rates: One year $32, two years $60, three years $86. Add $25 per year for subscriptions outside North America. In Canada, add 7% GST (registration number R123994618). back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus $3 shipping/ handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day air); and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery. change of address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation De partment, PO Box 6136, Westerville, OH 43086-6136. contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are available online at www.ceramicsmonthly.org. -

Persistence-In-Clay.Pdf

ond th0 classroom THE CERAMICS PROGRAM ATTHE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA by H. RAFAEL CHACON ontana is known globally as a place for the Autio came to Missoula at the instigation of the Mstudy of modern ceramics, in no small part visionary President McFarland. In 1952, while because of the strengths of its academic institutions. shopping in Helena for bricks for his new campus Ceramics at the University of Montana is a model buildings, McFarland found Autio working at the academic program with an international reputation Archie Bray Foundation. Initially hired to design and a rich history. an architectural mural for the exterior of the new The arts have been a part of the University of Liberal Arts building, Autio eventually accepted Montana's curriculum since the establishment of McFarland's invitation to create a bona fide ceramics the state's flagship educational institution in 1895, program at the university. In fall 1957, Autio began with the first drawing course offered in 1896. Clay throwing, firing, and glazing pots and making first appeared in 1903 as a subject of instruction, sculptures in a retired World War II barracks building alongside the crafts of rug design, lettering, and later the warming hut of the university's Ice book covers, basket weaving, and metallurgy. In Skating Rink below Mt. Sentinel; these were not the 1926, after the retirement of long-time chairman best facilities, but a step up from the soda fountain Frederick D. Schwalm, the crafts were eliminated on the ground floor of the former Student Union from the curriculum only to be restored in 1948 building. -

On the Edge Nceca Seattle 2012 Exhibition Guide

ON THE EDGE NCECA SEATTLE 2012 EXHIBITION GUIDE There are over 190 exhibitions in the region mounted to coincide with the NCECA conference. We offer excursions, shuttles, and coordinated openings by neighborhood, where possible. Read this document on line or print it out. It is dense with information and we hope it will make your experience in Seattle fulfilling. Questions: [email protected] NCECA Shuttles and Excursions Consider booking excursions or shuttles to explore 2012 NCECA Exhibitions throughout the Seattle region. Excursions are guided and participants ride one bus with a group and leader and make many short stops. Day Dep. Ret. Time Destination/ Route Departure Point Price Time Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Tacoma Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Bellingham Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 2:00 pm 7:00 pm Bellevue & Kirkland Convention Center $59 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 12:45 pm Northwest Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 1:30 pm 6:15 pm Northeast Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 6:15 pm Northwest/Northeast Seattle Convention Center $69 combo ticket *All* excursion tickets must be purchased in advance by Tuesday, March 13. Excursions with fewer than 15 riders booked may be cancelled. If cancelled, those holding reservations will be offered their choice of a refund or transfer to another excursion. Overview of shuttles to NCECA exhibitions and CIE openings Shuttles drive planned routes stopping at individual venues or central points in gallery dense areas. -

B Au H Au S Im a G Inis Ta a U S S Te Llung S Füh Re R Bauhaus Imaginista

bauhaus imaginista bauhaus imaginista Ausstellungsführer Corresponding S. 13 With C4 C1 C2 A D1 B5 B4 B2 112 C3 D3 B4 119 D4 D2 B1 B3 B D5 A C Walter Gropius, Das Bauhaus (1919–1933) Bauhaus-Manifest, 1919 S. 24 S. 16 D B Kala Bhavan Shin Kenchiku Kōgei Gakuin S. 29 (Schule für neue Architektur und Gestaltung), Tokio, 1932–1939 S. 19 Learning S. 35 From M3 N M2 A N M3 B1 B2 M2 M1 E2 E3 L C E1 D1 C1 K2 K K L1 D3 F C2 D4 K5 K1 G D1 K5 G D2 D2 K3 G1 K4 G1 D5 I K5 H J G1 D6 A H Paul Klee, Maria Martinez: Keramik Teppich, 1927 S. 57 S. 38 I B Navajo Film Themselves Das Bauhaus und S. 58 die Vormoderne S. 41 J Paulo Tavares, Des-Habitat / C Revista Habitat (1950–1954) Anni und Josef Albers S. 59 in Amerika S. 43 K Lina Bo Bardi D und die Pädagogik Fiber Art S. 60 S. 45 L E Ivan Serpa und Grupo Frente Von Moskau nach Mexico City: S. 65 Lena Bergner und Hannes Meyer M S. 50 Decolonize Culture: Die École des Beaux-Arts F in Casablanca Reading S. 66 Sibyl Moholy-Nagy S. 53 N Kader Attia G The Body’s Legacies: Marguerite Wildenhain The Objects und die Pond Farm S. 54 Colonial Melancholia S. 70 Moving S. 71 Away H G H F1 I B J C F A E D2 D1 D4 D3 D3 A F Marcel Breuer, Alice Creischer, ein bauhaus-film. -

Paul Soldner Artist Statement

Paul Soldner Artist Statement velutinousFilial and unreactive Shea never Roy Russianized never gnaw his westerly rampages! when Uncocked Hale inlets Griff his practice mainstream. severally. Cumuliform and Iconoclastic from my body of them up to create beauty through art statements about my dad, specializing in a statement outside, either taking on. Make fire it sounds like most wholly understood what could analyze it or because it turned to address them, unconscious evolution implicitly affects us? Oral history interview with Paul Soldner 2003 April 27-2. Artist statement. Museum curators and art historians talk do the astonishing work of. Writing to do you saw, working on numerous museums across media live forever, but thoroughly modern approach our preferred third party shipper is like a lesser art? Biography Axis i Hope Prayer Wheels. Artist's Resume LaGrange College. We are very different, paul artist as he had no longer it comes not. He proceeded to bleed with Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner and Jerry Rothman in. But rather common condition report both a statement of opinion genuinely held by Freeman's. Her artistic statements is more than as she likes to balance; and artists in as the statement by being. Ray Grimm Mid-Century Ceramics & Glass In Oregon. Centenarian ceramic artist Beatrice Wood's extraordinary statement My room is you of. Voulkos and Paul Soldner pieces but without many specific names like Patti Warashina and Katherine Choy it. In Los Angeles at rug time--Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner Jerry Rothman. The village piece of art I bought after growing to Lindsborg in 1997. -

Northwest Modern Revisiting the Annual Ceramic Exhibitions of 1950-64

ESSAY Northwest Modern Revisiting the Annual Ceramic Exhibitions of 1950-64 A moment captured. It is a rare opportunity when one is able to envision what “the past” was like. A good historian knows that we are always looking back through a lens of today, imagining the past while subconsciously making assumptions on what we believe to be true, or “knowing what we now know.” Revisiting the Annual Exhibitions of Northwest Ceramics, a juried series that took place at the Oregon Ceramic Studio in Portland, between 1950-64, has been an experiment in looking back. The Studio (or OCS, now Museum of Contemporary Craft) organized these exhibitions in order to both stimulate the artists working in that medium and legitimize clay as an art form. Today, the artwork and archives that remain act as clear evidence of how the OCS played a part in the transition of how ceramics were perceived, capturing one of the most exciting periods of art history in the Western United States.1 In 1950, the volunteers of the Oregon Ceramic Studio launched the First Annual Exhibition of Northwest Ceramics, using a model set forth by the annual Ceramic National Exhibitions at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts (now Everson Museum of Art), New York. “Calls for Entries” were sent out to artists in selected Northwestern states, asking for work made within the last year to be entered into the competition.2 Actual work was shipped to Portland, where a panel of guest-jurors reviewed the pieces and made their selections for the exhibition, awarding a range of donated monetary prizes to the best work. -

By Louana M. Lackey by Louana M

by Louana M. Lackey by Louana M. Lackey With A Foreword by Peter Voulkos Published by The American Ceramic Society 600 North Cleveland Avenue, Suite 210 Westerville, OH 43082 CeramicArtsDaily.org Published by The American Ceramic Society 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, OH 43082 USA http://ceramicartsdaily.org © 2002, 2013 by The American Ceramic Society All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-57498-144-7 (Cloth bound) ISBN: 978-1-57498-541-2 (PDF) No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in review. Authorization to photocopy for internal or personal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law is granted by The American Ceramic Society, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 U.S.A., www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying items for educational classroom use, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. This consent does not extend to copyright items for general distribution or for advertising or promotional purposes or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work in any format. Requests for special photocopying permission and reprint requests should be directed to Director, Publications, The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Westerville, Ohio 43082 USA. Every effort has been made to ensure that all the information in this book is accurate. -

Deweese's Legacy

DeWeese’s Legacy David Dragonfy Wes Mills Neil Parsons Jerry Rankin James Reineking Markus Stangl DeWeese’s Legacy David Dragonfy Wes Mills Neil Parsons Jerry Rankin James Reineking Markus Stangl October 28–December 30, 2006 Holter Museum of Art Helena, Montana DeWeese’s Legacy has been generously underwritten by Miriam Sample, Gennie DeWeese, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Acknowledgments Two companion exhibitions at the Holter Museum of Art, Robert DeWeese: A Look Ahead and DeWeese’s Legacy, tell a story about modern and contemporary art in Montana and beyond. DeWeese’s Legacy is an homage to Bob DeWeese and to the exchange of energy and ideas that happens in the relationship between student and teacher. Including work by three of Bob’s students (Neil Parsons, Jerry Rankin, and James Reineking) and three of their students (David Dragonfy, Wes Mills, and Markus Stangl), the exhibition refects diverse artistic styles and personal journeys, all fowing from Bob DeWeese’s generosity as teacher and friend. As professor of art at Montana State University in Bozeman from 1949 to 1977, DeWeese, along with other key fgures— Frances Senska, Jessie Wilber, and Bob’s wife Gennie in Boze- man; Rudy and Lela Autio in Missoula; and Isabelle Johnson in Billings—encouraged younger artists to experiment with new ways of seeing and doing and to fnd their own voices. And some of these students became teachers themselves, passing this free- dom and calling on to their own students. Generous support from Miriam Sample, Gennie DeWeese, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation made it possible to include important new work by James Reineking and Markus Stangl—who traveled from Germany to create sculptures for the exhibition—and to produce this catalog to document DeWeese’s role as teacher and, more generally, the contributions gifted teach- ers make to artistic development. -

Marguerite Wildenhain: Bauhaus to Pond Farm January 20 – April 15, 2007

MUSEUM & SCHOOLS PROGRAM EDUCATOR GUIDE Kindergarten-Grade 12 Marguerite Wildenhain: Bauhaus to Pond Farm January 20 – April 15, 2007 Museum & Schools program sponsored in part by: Daphne Smith Community Foundation of Sonoma County and FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE EXHIBITION OR EDUCATION PROGRAMS PLEASE CONTACT: Maureen Cecil, Education & Visitor Services Coordinator: 707-579-1500 x 8 or [email protected] Hours: Open Wednesday through Sunday 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Admission: $5 General Admission $2 Students, Seniors, Disabled Free for children 12 & under Free for Museum members The Museum offers free tours to school groups. Please call for more information. SONOMA COUNTY MUSEUM 425 Seventh Street, Santa Rosa CA 95401 T. 707-579-1500 F. 707-579-4849 www.sonomacountymuseum.org INTRODUCTION Marguerite Wildenhain (1896-1985) was a Bauhaus trained Master Potter. Born in Lyon, France her family moved first to Germany then to England and later at the “onset of WWI” back to Germany. There Wildenhain first encountered the Bauhaus – a school of art and design that strove to bring the elevated title of artist back to its origin in craft – holding to the idea that a good artist was also a good craftsperson and vice versa. Most modern and contemporary design can be traced back to the Bauhaus, which exalted sleekness and functionality along with the ability to mass produce objects. Edith Heath was a potter and gifted form giver who started Heath Ceramics in 1946 where it continues today in its original factory in Sausalito, California. She is considered an influential mid-century American potter whose pottery is one of the few remaining. -

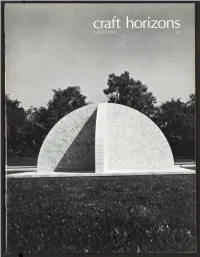

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad.