Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society the New-York Historical Society Holds

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society The New-York Historical Society holds one of the nation’s premiere collections of eighteenth-century American portraits. During this formative century a small group of native-born painters and European émigrés created images that represent a broad swath of elite colonial New York society -- landowners and tradesmen, and later Revolutionaries and Loyalists -- while reflecting the area’s Dutch roots and its strong ties with England. In the past these paintings were valued for their insights into the lives of the sitters, and they include distinguished New Yorkers who played leading roles in its history. However, the focus here is placed on the paintings themselves and their own histories as domestic objects, often passed through generations of family members. They are encoded with social signals, conveyed through dress, pose, and background devices. Eighteenth-century viewers would have easily understood their meanings, but they are often unfamiliar to twenty-first century eyes. These works raise many questions, and given the sparse documentation from the period, not all of them can be definitively answered: why were these paintings made, and who were the artists who made them? How did they learn their craft? How were the paintings displayed? How has their appearance changed over time, and why? And how did they make their way to the Historical Society? The state of knowledge about these paintings has evolved over time, and continues to do so as new discoveries are made. This exhibition does not provide final answers, but presents what is currently known, and invites the viewer to share the sense of mystery and discovery that accompanies the study of these fascinating works. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mohler, Melinda M., "A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4755. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4755 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jack Hammersmith, Ph.D., Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Kenneth Fones-World, Ph.D. Martha Pallante, Ph.D. -

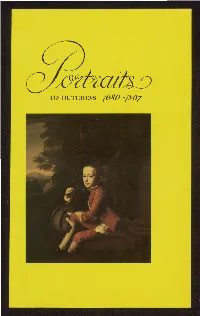

Portraits of Dutchess

OF DUTCHESS /680 ,.,/807 Cover: DANIEL CROMMELIN VERPLANCK 1762-1834 Painted by John Singlecon Copley in 1771 CottrteJy of The Metropolitan J\f11Jeum of Art New York. Gift of Bayard Verplanck, 1949 (See page 42) OF DUTCHESS /680-/807 by S. Velma Pugsley Spo11sored by THE DUTCHESS COUNTY AMERICAN REVOLUTION BICENTENNIAL COMMISSION as a 1976 Project Printed by HAMILTON REPRODUCTIONS, Inc. Poughkeepsie, N. Y. FOREWORD The Bicentennial Project rirled "Portraits of Dutchess 1680-1807" began as a simple, personal arrempr ro catalog existing porrrairs of people whose lives were part of rhe county's history in rhe Colonial Period. As rhe work progressed ir became certain rhar relatively few were srill in the Durchess-Purnam area. As so many of rhem had become the property of Museums in other localities it seemed more important than ever ro lisr rhem and their present locations. When rhe Dutchess County American Revolution Bicentennial Commission with great generosity undertook rhe funding ir was possible ro illustrate rhe booklet with photographs from rhe many available sources. This document is nor ro be considered as a geneological or historic record even though much research in rhose directions became a necessity. The collection is meant ro be a pictorial record, only, hoping rhar irs readers may be made more aware rhar these paintings are indeed pictures of our ancestors. Ir is also hoped rhar all museum collections of Colonial Painting will be viewed wirh deeper and more personal interest. The portraits which are privately owned are used here by rhe gracious consent of the owners. Those works from public sources are so indicated. -

Van Rensselaer Family

.^^yVk. 929.2 V35204S ': 1715769 ^ REYNOLDS HISTORICAL '^^ GENEALOGY COLLECTION X W ® "^ iiX-i|i '€ -^ # V^t;j^ .^P> 3^"^V # © *j^; '^) * ^ 1 '^x '^ I It • i^© O ajKp -^^^ .a||^ .v^^ ^^^ ^^ wMj^ %^ ^o "V ^W 'K w ^- *P ^ • ^ ALLEN -^ COUNTY PUBLIC LIBR, W:^ lllillllli 3 1833 01436 9166 f% ^' J\ ^' ^% ^" ^%V> jil^ V^^ -llr.^ ^%V A^ '^' W* ^"^ '^" ^ ^' ?^% # "^ iir ^M^ V- r^ %f-^ ^ w ^ '9'A JC 4^' ^ V^ fel^ W' -^3- '^ ^^-' ^ ^' ^^ w^ ^3^ iK^ •rHnviDJ, ^l/OL American Historical Magazine VOL 2 JANUARY. I907. NO. I ' THE VAN RENSSELAER FAMILY. BY W. W. SPOONER. the early Dutch colonial families the Van OF Rensselaers were the first to acquire a great landed estate in America under the "patroon" system; they were among the first, after the English conquest of New Netherland, to have their possessions erected into a "manor," antedating the Livingstons and Van Cortlandts in this particular; and they were the last to relinquish their ancient prescriptive rights and to part with their hereditary demesnes under the altered social and political conditions of modem times. So far as an aristocracy, in the strict understanding of the term, may be said to have existed under American institu- tions—and it is an undoubted historical fact that a quite formal aristocratic society obtained throughout the colonial period and for some time subsequently, especially in New York, — the Van Rensselaers represented alike its highest attained privileges, its most elevated organization, and its most dignified expression. They were, in the first place, nobles in the old country, which cannot be said of any of the other manorial families of New York, although several of these claimed gentle descent. -

H. Doc. 108-222

34 Biographical Directory DELEGATES IN THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS CONNECTICUT Dates of Attendance Andrew Adams............................ 1778 Benjamin Huntington................ 1780, Joseph Spencer ........................... 1779 Joseph P. Cooke ............... 1784–1785, 1782–1783, 1788 Jonathan Sturges........................ 1786 1787–1788 Samuel Huntington ................... 1776, James Wadsworth....................... 1784 Silas Deane ....................... 1774–1776 1778–1781, 1783 Jeremiah Wadsworth.................. 1788 Eliphalet Dyer.................. 1774–1779, William S. Johnson........... 1785–1787 William Williams .............. 1776–1777 1782–1783 Richard Law............ 1777, 1781–1782 Oliver Wolcott .................. 1776–1778, Pierpont Edwards ....................... 1788 Stephen M. Mitchell ......... 1785–1788 1780–1783 Oliver Ellsworth................ 1778–1783 Jesse Root.......................... 1778–1782 Titus Hosmer .............................. 1778 Roger Sherman ....... 1774–1781, 1784 Delegates Who Did Not Attend and Dates of Election John Canfield .............................. 1786 William Hillhouse............. 1783, 1785 Joseph Trumbull......................... 1774 Charles C. Chandler................... 1784 William Pitkin............................. 1784 Erastus Wolcott ...... 1774, 1787, 1788 John Chester..................... 1787, 1788 Jedediah Strong...... 1782, 1783, 1784 James Hillhouse ............... 1786, 1788 John Treadwell ....... 1784, 1785, 1787 DELAWARE Dates of Attendance Gunning Bedford, -

Historic Hudson Valley Library Manuscript Finding Aid

Historic Hudson Valley Library Manuscript Finding Aid Beekman Family Collection, 1721-1903 The Beekman family was part of the landed aristocracy of Colonial New York. Through inter-marriage, the Beekmans acquired alliances with the powerful Livingston and Van Cortlandt families. After the American Revolution, Gerard G. Beekman, Jr. was able to purchase a large part of the Philipse estate, which has been preserved by Historic Hudson Valley as Philipsburg Manor. The manuscript collection consists mainly of indentures, deeds and other legal documents pertaining mostly to the immediate family of Gerard G. Beekman, Jr. and his son Stephen D. Beekman. 68 items. Conklin and Chadeayne Family Collection, 1721-1903 The Conklins and Chadeaynes are two related families who resided on the Philipse and Van Cortlandt estates. The Conklins settled in New York about the year 1638, and a house built by Nathaniel Conklin (c.1740-1817) was still standing as of 1979 in Tarrytown. The Chadeayne family , who came to America from France as religious refugees, purchased land from William Skinner, a son-in-law and heir to Stephanus Van Cortlandt, in 1755 and built a homestead which remained in the Chadeayne family for over two centuries. This collection consists of legal papers, deeds, and wills connected with the estates of Nathaniel Conklin and Jacob Chadeayne. 29 items Hamilton Collection, 1786-1843, focus 1843 Alexander Hamilton (1816-1889) was the son of James A. Hamilton (1788-1879) and Mary Morris; grandson of Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804, Secretary of Treasury) and Elizabeth Schuyler (1757-1854, second daughter of Catherine and General John Philip Schuyler). -

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record

Consolidated Contents of The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record Volumes 1-50; 1870-1919 Compiled by, and Copyright © 2012-2013 by Dale H. Cook This file is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material directly from plymouthcolony.net, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement. Please contact [email protected] so that legal action can be undertaken. Any commercial site using or displaying any of my files or web pages without my express written permission will be charged a royalty rate of $1000.00 US per day for each file or web page used or displayed. [email protected] Revised June 14, 2013 The Record, published quarterly since 1870 by the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, is the second-oldest genealogical journal in the nation. Its contents include many articles concerning families outside of the state of New York. As this file was created for my own use a few words about the format of the entries are in order. The entries are listed by Record volume. Each volume is preceded by the volume number and year in boldface. Articles that are carried across more than one volume have their parts listed under the applicable volumes. This entry, from Volume 4, will illustrate the format used: 4 (1873):32-39, 94-98, 190-194 (Cont. from 3:190, cont. to 5:38) Records of the Society of Friends of the City of New York and Vicinity, from 1640 to 1800 Abraham S. Underhill The first line of an entry for an individual article or portion of a series shows the Record pages for an article found in that volume. -

Of Belligerent Humor: the End of Alexander Hamilton's Political

2I%HOOLJHUHQW+XPRU 7KH(QGRI$OH[DQGHU+DPLOWRQ¶V3ROLWLFDO&DUHHU 9HURQLFD&UX] $OH[DQGHU +DPLOWRQ LVFRQVLGHUHG RQH RI WKH )RXQGLQJ )DWKHUV RIWKH8QLWHG6WDWHVEXWPDQ\LQWKHFRXQWU\GRQRWIXOO\DSSUHFLDWHKLV FRQWULEXWLRQV +H EURXJKW WKH LQIDQW FRXQWU\ WKURXJK RQH RI WKHPRVW IUDJLOH WLPHV LQ LWV KLVWRU\ WKURXJK KLV ZRUN DV WKH 6HFUHWDU\ RI WKH 7UHDVXU\ +H ZDV DQ LPSRUWDQW PDQ DOWKRXJK KH FDPH IURP PHDJHU EHJLQQLQJVRQWKHLVODQGRI1HYLVLQWKH&DULEEHDQ+LVFKLOGKRRGZDV YHU\ GLIIHUHQW IURP WKH RWKHU )RXQGLQJ )DWKHUV OLNH 7KRPDV -HIIHUVRQ *HRUJH :DVKLQJWRQ -RKQ $GDPV DQG -DPHV 0DGLVRQ 7KH VRQ RI XQPDUULHGSDUHQWVKHJUHZXSLQDKRPHWKDWZDVQRWVRFLDOO\DFFHSWDEOH DQG KH GLG QRW UHFHLYH WKH VDPH OHYHO RI HGXFDWLRQ WKDW KLV SROLWLFDO FRXQWHUSDUWV UHFHLYHGDV\RXQJ FKLOGUHQ +RZHYHU KH ZDV DEOHWR SXOO KLPVHOI XS DQG DWWHQG .LQJ¶V &ROOHJH &ROXPELD 8QLYHUVLW\ LQ 1HZ <RUNDWRQO\IRXUWHHQ\HDUVROG+HZRXOGHYHQWXDOO\MRLQWKH5HYROXWLRQ DV D PHPEHU RI :DVKLQJWRQ¶V FORVH FLUFOH DQG ODWHU MRLQ KLV FDELQHW +DPLOWRQZDVDYHU\DPELWLRXVPDQZKRPD\ZHOOKDYHEHHQRQWKHURDG WREHFRPLQJWKH3UHVLGHQWRIWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV+LVDPELWLRQZRXOGJLYH KLP ERWK IULHQGV DQG IRHV +H ZDV D SROLWLFDO DQG HFRQRPLF JHQLXV ZKLFK PDGH KLP D KHUR WR WKH PHUFKDQW FODVVHV LQ 1HZ <RUN DQG D SROLWLFDO ULYDO RI -HIIHUVRQ 0DGLVRQ DQG $GDPV (YHQ ZLWK SROLWLFDO ULYDOV LQ ERWK SDUWLHV KH ZDV DEOH WR KDYH JUHDW VXFFHVV LQ ERWK KLV PLOLWDU\ DQG SROLWLFDO OLIH 'XULQJ WKH 5HYROXWLRQ KH OHG D VXFFHVVIXO FKDUJHDW<RUNWRZQ$VWKH6HFUHWDU\RIWKH7UHDVXU\KHSXWWRJHWKHUWKH 5HSRUW RI 3XEOLF &UHGLW 5HSRUW RQ D 1DWLRQDO %DQN DQG 5HSRUW RI 0DQXIDFWXUHV+HDOVRKHOSHGDVVXUHWKHHFRQRPLFVWDELOLW\RIWKH8QLWHG -

The Architecture of Slavery: Art, Language, and Society in Early Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 The architecture of slavery: Art, language, and society in early Virginia Alexander Ormond Boulton College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, Architecture Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Boulton, Alexander Ormond, "The architecture of slavery: Art, language, and society in early Virginia" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623813. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-3sgp-s483 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

01Kaminski Ch01 1-396.Qxd

The Thoughts and Words of Thomas Jefferson Advice s You will perceive by my preaching that I am grow ing old: it is the privilege of years, and I am sure you will pardon it from the purity of its motives. To Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., Paris, November 25, 1785 The greatest favor which can be done me is the communication of the opinions of judicious men, of men who do not suffer their judgments to be biased by either interest or passions. To Chandler Price, Washington, February 28, 1807 Your situation, thrown at such a distance from us, & alone, cannot but give us all great anxieties for you. As much has been secured for you, by your particular position and the acquaintance to which you have been recommended, as could be done to wards shielding you from the dangers which sur round you. But thrown on a wide world, among entire strangers, without a friend or guardian to ad vise, so young too, & with so little experience of mankind, your dangers are great, & still your safety must rest on yourself. A determination never to do what is wrong, prudence and good humor, will go 4 thoughts and words of thomas jefferson far towards securing to you the estimation of the world. To Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Washington, November 24, 1808 How easily we prescribe for others a cure for their difficulties, while we cannot cure our own. To John Adams, Monticello, January 22, 1821 Adore God. Reverence and cherish your parents. Love your neighbor as yourself, and your country more than yourself.