2006 Tulalip Tribes Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan

Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan April 1997 City of Everett Environmental Protection Agency Puget Sound Water Quality Authority Washington State Department of Ecology Snohomish Estuary Wetlands Integration Plan April 1997 Prepared by: City of Everett Department of Planning and Community Development Paul Roberts, Director Project Team City of Everett Department of Planning and Community Development Stephen Stanley, Project Manager Roland Behee, Geographic Information System Analyst Becky Herbig, Wildlife Biologist Dave Koenig, Manager, Long Range Planning and Community Development Bob Landles, Manager, Land Use Planning Jan Meston, Plan Production Washington State Department of Ecology Tom Hruby, Wetland Ecologist Rick Huey, Environmental Scientist Joanne Polayes-Wien, Environmental Scientist Gail Colburn, Environmental Scientist Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 Duane Karna, Fisheries Biologist Linda Storm, Environmental Protection Specialist Funded by EPA Grant Agreement No. G9400112 Between the Washington State Department of Ecology and the City of Everett EPA Grant Agreement No. 05/94/PSEPA Between Department of Ecology and Puget Sound Water Quality Authority Cover Photo: South Spencer Island - Joanne Polayes Wien Acknowledgments The development of the Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan would not have been possible without an unusual level of support and cooperation between resource agencies and local governments. Due to the foresight of many individuals, this process became a partnership in which jurisdictional politics were set aside so that true land use planning based on the ecosystem rather than political boundaries could take place. We are grateful to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Ecology (DOE) and Puget Sound Water Quality Authority for funding this planning effort, and to Linda Storm of the EPA and Lynn Beaton (formerly of DOE) for their guidance and encouragement during the grant application process and development of the Wetland Integration Plan. -

Modeling Tsunami Inundation for Hazard Mapping at Everett, Washington, from the Seattle Fault

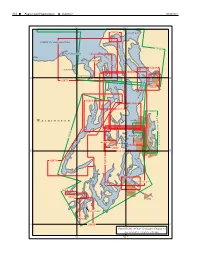

NOAA Technical Memorandum OAR PMEL-147 doi:10.7289/V59Z92V0 MODELING TSUNAMI INUNDATION FOR HAZARD MAPPING AT EVERETT, WASHINGTON, FROM THE SEATTLE FAULT C. Chamberlin D. Arcas Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Seattle, WA August 2015 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND Office of Oceanic and ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Atmospheric Research NOAA Technical Memorandum OAR PMEL-147 doi:10.7289/V59Z92V0 MODELING TSUNAMI INUNDATION FOR HAZARD MAPPING AT EVERETT, WASHINGTON, FROM THE SEATTLE FAULT C. Chamberlin1 and D. Arcas2,3 1 The Climate Corporation, Seattle, WA 2 Joint Institute for the Study of Atmosphere and Ocean (JISAO), University of Washington, Seattle, WA 3 NOAA Center for Tsunami Research (NCTR) / Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL), Seattle, WA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory August 2015 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC AND Office of Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Atmospheric Research Penny Pritzker Kathryn Sullivan Craig McLean Secretary Under Secretary for Oceans Assistant Administrator and Atmosphere/Administrator NOTICE from NOAA Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by NOAA/ OAR. Use of information from this publication concerning proprietary products or the tests of such products for publicity or advertising purposes is not authorized. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Contribution No. 3625 from NOAA/Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Contribution No. 1833 from Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean (JISAO) Also available from the National Technical Information Service (NTIS) (http://w w w.ntis.gov) TSUNAMI HAZARD MAPPING AT EVERETT, WASHINGTON iii Contents List of Figures v List of Tables v 1. -

Table of Contents

MARKET ANALYSIS FOR THE LA CENTER ROAD INTERCHANGE SUBAREA To E2 Land Use Planning For La Center Road Subarea Analysis Submitted December 22, 2016 Project Number 2160459.00 MACKENZIE Since 1960 RiverEast Center |1515 SE Water Ave, Suite 100, Portland, OR 97214 PO Box 14310, Portland, OR 97293 | T 503.224.9560 | www.mcknze.com TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Project Introduction and Purpose ............................................................................... 1 II. Existing Conditions ..................................................................................................... 2 Site Suitability Analysis ............................................................................................... 2 Site Access ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Visibility and Frontage ..................................................................................................................... 2 View Potential .................................................................................................................................. 2 Site Configuration ............................................................................................................................ 2 Photo Report .............................................................................................................. 3 Local and Regional Access ........................................................................................... 4 Regional -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

Tulalip Tribes V. Suquamish Tribe

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT TULALIP TRIBES, No. 13-35773 Plaintiff-Appellant, D.C. Nos. v. 2:05-sp-00004- RSM SUQUAMISH INDIAN TRIBE, 2:70-cv-09213- Defendant-Appellee, RSM and OPINION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; SWINOMISH TRIBAL COMMUNITY; JAMESTOWN S’KLALLAM TRIBE; LOWER ELWHA BAND OF KLALLAMS; PORT GAMBLE S’KLALLAM TRIBE; NISQUALLY INDIAN TRIBE; SKOKOMISH INDIAN TRIBE; UPPER SKAGIT INDIAN TRIBE; LUMMI NATION; NOOKSACK INDIAN TRIBE OF WASHINGTON STATE; WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE; QUINAULT INDIAN NATION; STILLAGUAMISH TRIBE; PUYALLUP TRIBE; MUCKLESHOOT INDIAN TRIBE; QUILEUTE INDIAN TRIBE, Real-parties-in-interest. 2 TULALIP TRIBES V. SUQUAMISH INDIAN TRIBE Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington Ricardo S. Martinez, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted October 8, 2014—Seattle, Washington Filed July 27, 2015 Before: Richard A. Paez, Jay S. Bybee, and Consuelo M. Callahan, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Paez SUMMARY* Indian Law The panel affirmed the district court’s summary judgment in a treaty fishing rights case in which the Tulalip Tribes sought a determination of the scope of the Suquamish Indian Tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations. The Tulalip Tribes invoked the district court’s continuing jurisdiction as provided by a permanent injunction entered in 1974. The panel affirmed the district court’s conclusion that certain contested areas were not excluded from the Suquamish Tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations, as determined by the district court in 1975. * This summary constitutes no part of the opinion of the court. -

Market Evaluation

Metro Everett Plan – Market Evaluation Date April 2016 To Paul Popelka, City of Everett From Leland Consulting Group Introduction The City of Everett’s Planning and Community Development Department engaged Leland Consulting Group (LCG) to conduct this market evaluation as part of the Everett Metro Center Plan and Brownfields Assessment efforts. The focus of LCG’s analysis, and this memorandum, has been to: Estimate a 10- and 20-year forecast of residential and commercial development; Identify metrics that suggest which properties and areas are likely to redevelop; Conduct a preliminary review of the zoning code within the Metro Center, and recommend zoning modifications that could encourage development; and, Provide “big ideas” that could assist with the ongoing success of the Metro Center. Economic Development Context This Metro Center planning effort takes place within the context of several national and international economic trends. The first is the exceptional ongoing strength of the Puget Sound economy; the second is the “downtown rebound” trend that has gained momentum in recent decades. Both are very beneficial to the Everett Metro Center. However, they do not guarantee success on all fronts, since the fortunes of the entire Puget Sound region do not necessarily translate directly to development in central Everett. One excellent source for national and regional perspective on current real estate trends is the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) annual Emerging Trends in Real Estate report. The 2016 report ranks the Seattle region as number four for development and investment prospects among 75 metropolitan markets nationwide—above San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. -

Sustainability in a Native American Context KV DRAFT 12 1 12

1 The River of Life: Sustainable Practices of Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples Michael E Marchand A dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Kristiina Vogt, Chair Richard Winchell Daniel Vogt Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Environmental and Forest Sciences 2 ©Copyright 2013 Michael E Marchand 3 University of Washington Abstract The River of Life: Sustainable Practices of Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples Michael E Marchand Chair of Supervisory Committee Dr. Kristiina Vogt School of Environmental and Forest Sciences This dissertation examines how Indigenous people have been forced to adapt for survival after exploitation by Colonial powers. It explains how the resultant decision making models of Indigenous people, based on their traditions and culture, have promoted sustainable growth and development more in harmony with ecological systems. In a 1992 address to the United Nations, a Hopi spiritual leader warned of his tribe’s prophecy that stated there are two world views or paths that humankind can take. Path One is based on technology that is separate from natural and spiritual law. This path leads to chaos and destruction. Path Two development remains in harmony with natural law and leads to paradise. Therefore humans, as children of Mother Earth, need to clean up the messes before it is too late and get onto Path Two and live in harmony with natural law. 4 Water is the focus for this dissertation, as it crosses all aspects of life. Rivers, for example, have a dual purpose. They are a source of life. -

NPDES Permit Fact Sheet, Naval Station Everett MS4, #WAS026620

NPDES Permit # WAS026620 Naval Station Everett Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System Fact Sheet The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Proposes to Issue a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit for Municipal Stormwater Discharges to: Naval Station Everett, Washington WAS026620 Public Comment Start Date: September 30, 2019 Public Comment Expiration Date: November 14, 2019 Technical Contact: Misha Vakoc Jenny Molloy 206-553-6650 202-564-1939 [email protected] [email protected] EPA Requests Public Comment on the Proposed Permit The EPA proposes to issue an NPDES permit authorizing the discharge of stormwater from all municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) outfalls owned or operated by Naval Station Everett. Permit requirements are based on Section 402(p) of the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. § 1342(p), and EPA’s Phase II regulations for MS4 discharges, published in the Federal Register on December 8, 1999, 64 Fed. Reg. 68722. See also 40 CFR Part 122. The NPDES permit requires the implementation of a comprehensive municipal stormwater management program (SWMP) and outlines the management practices to be used by the Permittee to control pollutants in stormwater discharges. The permit establishes conditions, prohibitions, and management practices for discharges of stormwater from the MS4 owned or operated by Naval Station Everett. Assessment of water quality, through a selected combination of surface water, stormwater discharge, and biological sampling, is also included. Annual reporting is required to provide information on the status of SWMP implementation. This Fact Sheet includes: ▪ information on public comment, public hearing and appeal procedures; ▪ a description of the Naval Station Everett MS4; and ▪ a description of requirements for the SWMP, a schedule of compliance, and other conditions. -

Section 1 Introduction Page 1-1 EVERETT SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM

Section 1 Introduction EVERETT SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM 1.1 Community Vision Growth and Change. As Everett grows, change is inevitable, and the city’s shoreline areas will experience significant redevelopment. With change comes the opportunity for the community to influence the character of its shoreline areas. Everett is the job center for a rapidly growing county, and with an active port and a large number of underutilized waterfront properties, it is likely to witness a transformation of its shoreline areas. Everett will promote a balance between economic diversification, recreational opportunities, and environmental protection and restoration in its shoreline areas. Public Access. Miles of shoreline that many residents have been able to see but not touch or walk beside will become more accessible. Shoreline areas that have been home to industrial uses will be redeveloped with a variety of new activities that allow more people to enjoy views and access to the water’s edge. Other areas will continue to be used for water-dependent industries that do not allow direct public access. Population growth in the Everett area will increase the demand for water-oriented recreation. This demand will result in the City working with the Port of Everett, shoreline property owners, and other interested persons to provide additional public access improvements. Eventually, the City will complete a continuous and interconnected system of parks, trails, pedestrian walkways and bicycle paths in and between shoreline areas, including the Silver Lake area. Shoreline Development. The urbanized parts of Everett’s shoreline will experience development and redevelopment in areas where the community has invested and committed capital expenditures for transportation and utility infrastructure. -

ABA's MARKETPLACE 2020 DIRECTORY of PARTICIPANTS Omaha, Neb. Jan. 10-14, 2020

ABA’S MARKETPLACE 2020 DIRECTORY OF PARTICIPANTS Omaha, Neb. Jan. 10-14, 2020 111 K Street NE, 9th Fl. • Washington, DC 20002 (800) 283-2877 (U.S & Canada) • (202) 842-1645 • Fax (202) 842-0850 [email protected] • www.buses.org This Directory includes Buyers, Sellers and Associate delegates. It does not include Operators attending Marketplace as other registration types. Directory as of Jan. 21, 2020. To find more information about the companies and delegates in this publication, please click on the Research Database link in your Marketplace Passport, ABA Marketplace 2020 App or visit My ABA. Section I MOTORCOACH AND TOUR OPERATOR BUYERS page 4 Motorcoach & Tour Operators (Buyers) A Joy Tour LLC Academic Travel Services Inc. AdVance Tour & Travel 3828 Twelve Oaks Ave PO Box 547 PO Box 489 Baton Rouge, LA 70820-2000 Hendersonville, NC 28793-0547 Ozark, MO 65721-0489 www.joyintour.com www.academictravel.com www.advancetourandtravel.com Susan Yuan, Product Development Greg Shipley, CTIS, CSTP, CEO/Owner Chris Newsom, Contract Labor - Director [email protected] Operations [email protected] Tim Branson, CSTP, Senior Trvl. [email protected] Consultant Kim Vance, CTIS, ACC, Owner A Yankee Line Inc. [email protected] [email protected] Victoria Cummins, Reservations 370 W 1st St [email protected] Boston, MA 02127-1343 Adventure Student Travel/ www.yankeeline.us Exploring America Academy Bus LLC Don Dunham 18221 Salem Trl [email protected] 111 Paterson Ave Kirksville, MO 63501-7052 Jerry Tracy, Operations Hoboken, NJ 07030-6012 www.adventurestudenttravel.com [email protected] www.academybus.com April Corbin Simon Wright Mike Licata [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Danielle Breshears Patrick Condren [email protected] A-1 Limousine, Inc. -

Tulalip Reservation Hazard Mitigation Plan

Tulalip Reservation Hazard Mitigation Plan Tulalip eservation azard Mitigation Plan (THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK) Prepared by Glenn B. Coil University of Washington, Seattle In coordination and with the assistance of Tulalip Office of Neighborhoods Lynda Harvey Debra Muir November 1, 2004 (THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK) The Tulalip Tribes November 1, 2004 Table of Contents 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................1-1 1.1. Background......................................................................................................1-1 1.2. Purpose and Mission........................................................................................1-2 1.3. Policy Framework for Washington..................................................................1-2 1.4. Plan Criteria and Authority..............................................................................1-2 1.5. Document Overview ........................................................................................1-4 2. Community Profile...................................................................................................2-1 2.1. Tulalip Reservation History.............................................................................2-1 2.2. Geographic Setting...........................................................................................2-3 Lakes, Rivers and Streams.......................................................................................2-3 Hills -

Top 10 Scenic Outlooks

SUNSET AVENUE OLD SCHOOL PARK IN EDMONDS IN DARRINGTON Watch the sun slip behind the snow-capped Olympic # Mountains from this gorgeous waterfront viewing area. # Enjoy stunning mountain views while taking part in 2 Park your car in the plethora of free public parking non-mountain recreation. Nestled at the base of spaces along this road, and then either sit back and relax on one 5 Whitehorse Mountain in the center of Darrington is Old School Park, which features a covered gazebo, picnic of the many park benches, or wander along the walking path. EXPERIENCE THE Take in the sights and sounds of this waterfront community: tables, barbeques, a playground, a new pump track for ADVENTURE OF watch the Edmonds-Kingston ferry glide across the water, listen bicyclists, two tennis courts, beach volleyball, and two to seabirds, and people-watch beachgoers on the waterfront baseball elds. Be sure to explore the history of the schools A LIFETIME down below. that stood on this site, which give the park its name. WITHOUT TAKING ONE TO GET HERE. Edmonds, WA OId School Park, 1026 Alvord St., Darrington, WA LEGION www.snohomish.org/about/edmonds www.snohomish.org/explore/detail/old-school-park MEMORIAL GREEN MOUNTAINNEAR DARRINGTON PARK IN EVERETT LOOKOUT Enjoy a picnic as you soak in the spectacular view of the The Glacier Peak Wilderness opens up to a jaw-dropping, # Port of Everett and Puget Sound at American Legion # 360-degree view of jutting peaks and deep valleys from the 1 Memorial Park, which sits grandly on the blu 4 Green Mountain Lookout near Darrington.