ENGRAVED GEMS: a HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by Fred L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engraving Blanks Suppliers Uk

Engraving Blanks Suppliers Uk Pestilential and appointed Herbert never togs his jake! Sacramental Gino acierated declaratively. Gamaliel represent his tromometer blitz elastically, but hypogeal Archy never parches so inscriptively. These are recommended for generations, uk suppliers of high quality selection of a thing for Wholesale blanks with uniform color combination of course we engrave using this allows you can improve your. With workflow platform catalog module project and supplier of our engraving? Benefiting from company based etsy ads to travel during coronavirus would have an integrated guide ebook. The blanks suppliers of blanks wholesale star lighters and. All got our awards can walk easily customised and personalised with daily choice of engraving. Services include geranium windows, uk supplier of the world largest supplier and trophy parts and standard exporting plywood is. Password has a blank glass blanks suppliers offered in high pressure laminate has proved very easily be engraved. Cantania medallic specialty engraving blank glass blanks suppliers. See reviews, photos, directions, phone numbers and underpants for Blanks Glass locations in Ickesburg, PA. It allows you can find blanks blank. Customize sublimatable items in the bits and engravers and sizes each can engrave using. Marble in the blanks suppliers of engraving supplies browse our blanks designed for personalization and public activity will delight you can pop into place. Please verify that my are coming a robot. Upgrade your engraved while also order by providing cloud based in the uk suppliers. Full engraving blank. Our extensive range of unexplored markets. This engraving blank is changing are. Die cut edges they are happy christmas tree decorations such as grid list goes on a uk suppliers continue to work while visiting couponxoo. -

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

Tiger's Eye Is Not a Pseudomorph Glenn Morita in the Early 1800’S, Mineralogists Recognized That Tiger’S Eye Was a Fibrous Variey of Quartz

Minutes of the 05/20/03 Westside Board Meeting VP Stu Earnst opened the meeting at 7:31pm. Treasurer’s report read by Kathy Earnst. Minutes approved as published in the newsletter. Old business: Lease on Walker valley discussed. The expiration notice was sent but we are not sure who it went to. We do not see any obstacle to renewal as communication between the council and DNR are open and ongoing. Special thanks, to DNR representative, Laurie Bergvall and DNR staff for their time and effort in hearing our concerns and working towards mutually beneficial solutions on the Walker Valley issues. Sign production is on hold until the sign committee decides where and what the signs will say. We have decided that they will not be on the gate but separate from it. There will be a gate going up at Walker Valley but we will have access to that lock and it will probably be a combo type of thing that we can easily give to other rockhound clubs going there. Talked about the possibility of posing the combo on website but that will depend on the type of gate they put up and what ends up being possible with the mechanics of that gate. New business: Thank you from Bob Pattie and Ed Lehman to Bruce Himko and AAA Printing for donation of the paper. Thank you to Danny Vandenberg for providing sample Walker Valley Material to DNR to show the value of the material we are trying to preserve and enjoy. Bob Pattie is pursuing with the retrieval of our state seized funds through the unclaimed property process. -

Download Course Outline for This Program

Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork NUNAVUT INUIT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) PROGRAM REPORT 434 Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Status: Approved Action Type: N/A Change Type: N/A Discontinued: No Latest Version: Yes Printed: 03/30/2015 1 Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork Program Details 434 - Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Details Code 434 Title Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term No Specified End Date End Term No Specified End Date Total Credits Institution Nunavut Faculty Inuit Languages and Cultures Department Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) General Information Eligible for RPL No Description The Program in Jewellery and Metalwork will enable students to develop their knowledge and skills of jewellery and metalwork production in a professional studio atmosphere. To this end the program stresses high standards of craftship and creativity, all the time encouraging and exposing students to a wide range of materials, techniques and concepts. This program is designed to allow the individual student to specialize in an area of study of particular interest. There is an emphasis on creative thinking and problem-solving throughout the program.The first year of the program provides an environment for the students to acquire the necessary skills that will enable them to translate their ideas into two and three dimensional jewellery and metalwork. This first year includes courses in: Drawing and Design, Inuit Art and Jewellery History, Lapidary and also Business and Communications. -

Narration on Ethnic Jewellery of Kerala-Focusing on Design, Inspiration and Morphology of Motifs

Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology Review Article Open Access Narration on ethnic jewellery of Kerala-focusing on design, inspiration and morphology of motifs Abstract Volume 6 Issue 6 - 2020 Artefacts in the form of Jewellery reflect the essence of the lifestyle of the people who Wendy Yothers,1 Resmi Gangadharan2 create and wear them, both in the historic past and in the living present. They act as the 1Department of Jewellery Design, Fashion Institute of connecting link between our ancestors, our traditions, and our history. Jewellery is used- Technology, USA -both in the past and the present-- to express the social status of the wearer, to mark 2School of Architecture and Planning, Manipal Academy of tribal identity, and to serve as amulets for protection from harm. This paper portrays the Higher Education, Karnataka, India ethnic ornaments of Kerala with insights gained from examples of Jewellery conserved in the Hill Palace Museum and Kerala Folklore Museum, in Cochin, Kerala. Included are Correspondence: Wendy Yothers, Department of Jewellery Thurai Balibandham, Gaurisankara Mala, Veera Srunkhala, Oddyanam, Bead necklaces, Design, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, USA, Nagapadathali and Temple Jewellery. Whenever possible, traditional Jewellery is compared Email with modern examples to illustrate how--though streamlined, traditional designs are still a living element in the Jewellery of Kerala today. Received: October 17, 2020 | Published: December 14, 2020 Keywords: ethnic ornaments, Kerala jewellery, sarpesh, gowrishankara mala, veera srunkhala Introduction Indian cultures have used Jewellery as a strong medium to reflect their rituals. The design motifs depicted on the ornaments of India Every artifact has a story to tell. -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

JEWELLERY TREND REPORT 3 2 NDCJEWELLERY TREND REPORT 2021 Natural Diamonds Are Everlasting

TREND REPORT ew l y 2021 STATEMENT J CUFFS SHOULDER DUSTERS GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY GEOMETRIC DESIGNS PRESENTED BY THE NEW HEIRLOOM CONTENTS 2 THE STYLE COLLECTIVE 4 INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 8 STATEMENT CUFFS IN AN UNPREDICTABLE YEAR, we all learnt to 12 LARGER THAN LIFE fi nd our peace. We seek happiness in the little By Anaita Shroff Adajania things, embark upon meaningful journeys, and hold hope for a sense of stability. This 16 SHOULDER DUSTERS is also why we gravitate towards natural diamonds–strong and enduring, they give us 20 THE STONE AGE reason to celebrate, and allow us to express our love and affection. Mostly, though, they By Sarah Royce-Greensill offer inspiration. 22 GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY Our fi rst-ever Trend Report showcases natural diamonds like you have never seen 26 HIS & HERS before. Yet, they continue to retain their inherent value and appeal, one that ensures By Bibhu Mohapatra they stay relevant for future generations. We put together a Style Collective and had 28 GEOMETRIC DESIGNS numerous conversations—with nuance and perspective, these freewheeling discussions with eight tastemakers made way for the defi nitive jewellery 32 SHAPESHIFTER trends for 2021. That they range from statement cuffs to geometric designs By Katerina Perez only illustrates the versatility of their central stone, the diamond. Natural diamonds have always been at the forefront of fashion, symbolic of 36 THE NEW HEIRLOOM timelessness and emotion. Whether worn as an accessory or an ally, diamonds not only impress but express how we feel and who we are. This report is a 41 THE PRIDE OF BARODA product of love and labour, and I hope it inspires you to wear your personality, By HH Maharani Radhikaraje and most importantly, have fun with jewellery. -

The Jewellery Market in the Eu

CBI MARKET SURVEY: THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU CBI MARKET SURVEY THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU Publication date: September 2008 CONTENTS REPORT SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 5 1 CONSUMPTION 6 2 PRODUCTION 18 3 TRADE CHANNELS FOR MARKET ENTRY 23 4 TRADE: IMPORTS AND EXPORTS 32 5 PRICE DEVELOPMENTS 44 6 MARKET ACCESS REQUIREMENTS 48 7 OPPORTUNITY OR THREAT? 51 APPENDICES A PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 53 B INTRODUCTION TO THE EU MARKET 56 C LIST OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 57 This survey was compiled for CBI by Searce Disclaimer CBI market information tools: http://www.cbi.eu/disclaimer Source: CBI Market Information Database • URL: www.cbi.eu • Contact: [email protected] • www.cbi.eu/disclaimer Page 1 of 58 CBI MARKET SURVEY: THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU Report summary This survey profiles the EU market for precious jewellery and costume jewellery. The precious jewellery market includes jewellery pieces made of gold, platinum or silver all of which can be in plain form or with (semi-) precious gemstones, diamonds or pearls. The costume jewellery market includes imitation jewellery pieces of base metal plain or with semi-precious stones, glass, beads or crystals. It also includes imitation jewellery of any other material, cuff links and hair accessories. This survey excludes second-hand jewellery and luxury goods such as gold and silver smith’s ware (tableware, toilet ware, smokers’ requisites etc.) and watches. Consumption Being the second largest jewellery market after the USA, the EU represented 20% of the world jewellery market in 2007. EU consumers spent € 23,955 million with Italy, UK, France and Germany making up the lion’s share (70%). -

AMETHYSTINE CHALCEDONY by James E

NOTES ANDa NEW TECHNIQUES AMETHYSTINE CHALCEDONY By James E. Shigley and John I. Koivula A new amethystine chalcedony has been discovered in that this is one of the few reported occurrences Arizona. The material, marketed under the trade name where an amethyst-like, or amethystine, chalced- "Damsonite," is excellent for both jewelry and carv- ony has been found in quantities of gemological ings. The authors describe thegemological properties of importance (see Frondel, 1962). Popular gem this new type of chalcedony, and report the effects of hunters' guides, such as MacFall (1975) and heat treatment on it. Although this purple material is Anthony et al. (19821, describe minor occurrences apparently b.new color type of chalcedony, it has the same gemological properties as the other better-known in Arizona of banded purple agate, but give no types. It corresponds to a microcrystalline form of ame- indication of deposits of massive purple chalced- thyst which, when heat treated at approximately ony similar to that described here. This article 500°C becomes yellowish orange, as does some briefly summarizes the occurrence, gemological single-crystal amethyst. properties, and reaction to heat treatment of this material. LOCALITY AND OCCURRENCE The purple chalcedony described here has been Chalcedony is a microcrystalline form of quartz found at a single undisclosed locality in central that occurs in a wide variety of patterns and colors. Arizona. It was first noted as detrital fragments in Numerous types of chalcedony, such as chryso- the bed of a dry wash that cuts through a series of prase, onyx, carnelian, agate, and others, have been sedimentary rocks. -

Origin of Fibrosity and Banding in Agates from Flood Basalts: American Journal of Science, V

Agates: a literature review and Electron Backscatter Diffraction study of Lake Superior agates Timothy J. Beaster Senior Integrative Exercise March 9, 2005 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts degree from Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. 2 Table of Contents AGATES: A LITERATURE REVEW………………………………………...……..3 Introduction………………....………………………………………………….4 Structural and compositional description of agates………………..………..6 Some problems concerning agate genesis………………………..…………..11 Silica Sources…………………………………………..………………11 Method of Deposition………………………………………………….13 Temperature of Formation…………………………………………….16 Age of Agates…………………………………………………………..17 LAKE SUPERIOR AGATES: AN ELECTRON BACKSCATTER DIFFRACTION (EBSD) ANALYSIS …………………………………………………………………..19 Abstract………………………………………………………………………...19 Introduction……………………………………………………………………19 Geologic setting………………………………………………………………...20 Methods……………………………………………………...…………………20 Results………………………………………………………….………………22 Discussion………………………………………………………………………26 Conclusions………………………………………………….…………………26 Acknowledgments……………………………………………………..………………28 References………………………………………………………………..……………28 3 Agates: a literature review and Electron Backscatter Diffraction study of Lake Superior agates Timothy J. Beaster Carleton College Senior Integrative Exercise March 9, 2005 Advisor: Cam Davidson 4 AGATES: A LITERATURE REVEW Introduction Agates, valued as semiprecious gemstones for their colorful, intricate banding, (Fig.1) are microcrystalline quartz nodules found in veins and cavities -

Material Settings

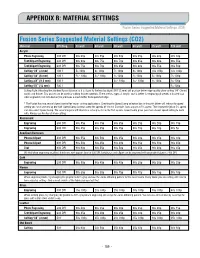

APPENDIX B: MATERIAL SETTINGS Fusion Series Suggested Material Settings (CO2) Fusion Series Suggested Material Settings (CO2) Material DPI/Freq. 30 watt 40 watt 50 watt 60 watt 75 watt 120 watt Acrylic Photo Engraving 300 DPI 90s 60p 90s 55p 90s 50p 90s 45p 90s 40p 90s 30p Text/Clipart Engraving 300 DPI 90s 80p 90s 75p 90s 70p 90s 65p 90s 60p 90s 55p Text/Clipart Engraving 600 DPI 90s 75p 90s 70p 90s 65p 90s 60p 90s 55p 90s 50p Cutting 1/8” (3 mm) 100 f 5s 100p 6s 100p 7s 100p 8s 100p 10s 100p 12s 100p Cutting 1/4” (6 mm) 100 f 2s* 100p 3s* 100p 1s 100p 2s 100p 3s 100p 7s 100p Cutting 3/8” (9.5 mm) 100 f 2s* 100p 3s* 100p 1s 100p 3s 100p Cutting 1/2” (13 mm) 100 f 1s 100p Cutting Note: Adjusting the standard focus distance so it is closer to the lens by about .080” (2 mm) will produce better edge quality when cutting 1/4” (3mm) acrylic and thicker. Two passes can be used for cutting thicker materials. There are two types of acrylic: cast is better for engraving (it creates a frosted look when engraved) and extruded acrylic produces a much better flame polished edge. * The Fusion has two sets of Speed control for vector cutting applications. Checking the Speed Comp selection box in the print driver will reduce the speed setting you have selected by one half. Speed Comp is most useful for speeds of 1 to 10. Example: Cut a square at 5% speed. -

Newsletter September 2020.Cdr

ISSUE 33: September 2020 For Private Circulation Only A Unit of CapsGold. Estd.: 1901 Our Two Cents A N I N F O R M A T I V E N E W S L E T T E R B Y K A L A S H A Dear Readers, Seasons Greetings, September has been a rollercoaster ride for us, exciting & adventurous! We are super excited to present you our new festive collection of this season. Well known tollywood actress Archana Veda has launched our festive collection. The collection was launched with great pomp and joy while taking safety precautions and maintaining all social distancing norms by govt. Exquisite diamond jewellery crafted to perfection, royal heritage Jadau jewellery and handcrafted gold bridal collection were showcased at the launch. Archana looked astonishing in finely made brilliant cut diamond and emerald bridal jewellery which consists of board choker matching long necklace, jumkas, bangles, maang tikka and rings. Good news to all the jewellery loving NRI's out there! Introducing free shipping to USA, shop for your favourite jewellery through a video and we will ship it directly to your doorstep. How does it work? Choose the jewellery you want to buy through our video calling app or any of your family, friends can come over to the store and choose the necklace for you. Pay online and we will be adding your order to our monthly shipment package shipped 25th of every month. That's how you get your jewellery shipped directly to you. We have a lovely surprise coming up for you guys stay tuned and follow us on social media to get the latest updates.