Samuel Alfred Mitchell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helium Mrs. Ahng the Second Lightest Element on Earth, Helium Is One Of

Helium Mrs. Ahng The second lightest element on Earth, Helium is one of the most important elements in our universe. It is the reason that we have sunlight, it makes balloons float, and used to cool down nuclear reactors. Although it is a simple noble gas with only two protons and two electrons, it is a powerful and essential resource. Discovered in1868 by astronomer Pierre Janssen while studying a solar eclipse; he noticed a yellow line around sun that had a wavelength that he had not seen before. English Astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer later named the element after the Greek word “Helios”, making the connection to how it was discovered. Helium only makes ups less than 1% of Earth’s atmosphere because of how light it is. It’s atomic mass is only 4.003, so the surrounding air is heavier than helium. An example of the difference in mass can be seen when comparing a helium filled balloon to a balloon filled with a mixture of atmospheric gases. The mass of the mixture is much heavier, and therefore is more effected by gravitational pull. Helium is found mostly in space in the core of stars, but it was also found on Earth in 1895 trapped underground. Scientists believe that the Helium that we harvest today was created during the creation of the universe, or the “Big Bang”. Only two electrons energize one orbital for this element, giving us the popular image for all atoms. With the outer orbital shell full, the element is referred to as inert and nonreactive. -

![Arxiv:0906.0144V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 31 May 2009 Event](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2044/arxiv-0906-0144v1-physics-hist-ph-31-may-2009-event-142044.webp)

Arxiv:0906.0144V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 31 May 2009 Event

Solar physics at the Kodaikanal Observatory: A Historical Perspective S. S. Hasan, D.C.V. Mallik, S. P. Bagare & S. P. Rajaguru Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, India 1 Background The Kodaikanal Observatory traces its origins to the East India Company which started an observatory in Madras \for promoting the knowledge of as- tronomy, geography and navigation in India". Observations began in 1787 at the initiative of William Petrie, an officer of the Company, with the use of two 3-in achromatic telescopes, two astronomical clocks with compound penduumns and a transit instrument. By the early 19th century the Madras Observatory had already established a reputation as a leading astronomical centre devoted to work on the fundamental positions of stars, and a principal source of stellar positions for most of the southern hemisphere stars. John Goldingham (1796 - 1805, 1812 - 1830), T. G. Taylor (1830 - 1848), W. S. Jacob (1849 - 1858) and Norman R. Pogson (1861 - 1891) were successive Government Astronomers who led the activities in Madras. Scientific high- lights of the work included a catalogue of 11,000 southern stars produced by the Madras Observatory in 1844 under Taylor's direction using the new 5-ft transit instrument. The observatory had recently acquired a transit circle by Troughton and Simms which was mounted and ready for use in 1862. Norman Pogson, a well known astronomer whose name is associated with the modern definition of the magnitude scale and who had considerable experience with transit instruments in England, put this instrument to good use. With the help of his Indian assistants, Pogson measured accurate positions of about 50,000 stars from 1861 until his death in 1891. -

A Propensity for Genius: That Something Special About Fritz Zwicky (1898 - 1974)

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 42 Number 1 Article 2 2-2006 A Propensity for Genius: That Something Special About Fritz Zwicky (1898 - 1974) John Charles Mannone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Mannone, John Charles (2006) "A Propensity for Genius: That Something Special About Fritz Zwicky (1898 - 1974)," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 42 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol42/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mannone: A Propensity for Genius A Propensity for Genius: That Something Special About Fritz Zwicky (1898 - 1974) by John Charles Mannone Preface It is difficult to write just a few words about a man who was so great. It is even more difficult to try to capture the nuances of his character, including his propensity for genius as well as his eccentric behavior edging the abrasive as much as the funny, the scope of his contributions, the size of his heart, and the impact on society that the distinguished physicist, Fritz Zwicky (1898- 1974), has made. So I am not going to try to serve that injustice, rather I will construct a collage, which are cameos of his life and accomplishments. In this way, you, the reader, will hopefully be left with a sense of his greatness and a desire to learn more about him. -

12-Inch Alvan Clark Telescope Restoration

12-Inch Alvan Clark Telescope Restoration: Summary of Research and Final Recommendations Deborah Culmer and Hannah Johnson September, 2011 Introduction The first telescope installed at Lick Observatory was a second-hand purchase, with the telescope and its optic made by the premier telescope makers of the time, Alvan Clark and Sons of Cambridge, MA. The dome that housed it was the first structure built on Mt. Hamilton, from bricks fired in a kiln on location. That dome still stands; and until the 1970’s, the 12-inch refracting telescope was in operation, but without its original driver clock and gears (replaced with an electronic drive, perhaps in the 1950’s). Since it was decommissioned, the 12-inch has been in storage. The Lick Instrument Lab has retrieved it, and it is currently on location at UC Santa Cruz in anticipation of total restoration. In the summer of 2011, a research project was launched to determine to what era and condition the telescope should be restored. In recent years, there has been great interest in historical restoration of Alvan Clark telescopes (and others, to be sure). As a result of that interest, we had a pool of organizations and institutions from which to glean information. Two we visited in person; many more we contacted via email and conference calls. Based on our research and interviews, we offer our recommendations on the restoration of this historically important telescope. 1. Research In beginning this project, it was very important to understand the history of the 12-inch Alvan Clark, especially since it was the first telescope set up on Mt. -

Solar Observatory

SOLAR OBSERVATORY Fig. 1. The Watson Solar Observatory c. 1920. Below the building was a twenty foot deep cellar, and a 55 foot horizontal shaft through the hill to a reflector at the surface on the north side. This building was erected by Professor James C. Watson using his own money and labor. Because of the stone reading "Watson Solar Observatory", the building became known as the Watson Mystery House. [series 9/1 Solar Obser- vatory folder, jf-4] The Solar Observatory was built by astronomer James Watson, with his own funds and labor for the purpose of looking for a hypothetical planet near the sun. The experiment did not reveal the planet, and the building was used for storage until its demolition in 1949. hen C. C. Washburn agreed to build an observatory for the University in 1876, the legisla- ture appropriated $3000 per year to fund the staffing and operation of the observatory. The Wperson hired for this job by President Bascom was James Craig Watson, the director of the observatory at Ann Arbor, Michigan. Watson had been a prodigy in astronomy, and was published at 19. His major professor Brunnow, when reproached for the small size of his teaching load exclaimed, "Yes I have only one student, but that one is Watson!"1 Watson became director of Michigan's obser- vatory at age 25 in 1863. Within a year he had discovered the first of what are called Watson's family of asteroids. In July of 1878 Watson went to Separation, Wyoming to observe a solar eclipse. -

Download This Article (Pdf)

244 Trimble, JAAVSO Volume 43, 2015 As International as They Would Let Us Be Virginia Trimble Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575; [email protected] Received July 15, 2015; accepted August 28, 2015 Abstract Astronomy has always crossed borders, continents, and oceans. AAVSO itself has roughly half its membership residing outside the USA. In this excessively long paper, I look briefly at ancient and medieval beginnings and more extensively at the 18th and 19th centuries, plunge into the tragedies associated with World War I, and then try to say something relatively cheerful about subsequent events. Most of the people mentioned here you will have heard of before (Eratosthenes, Copernicus, Kepler, Olbers, Lockyer, Eddington…), others, just as important, perhaps not (von Zach, Gould, Argelander, Freundlich…). Division into heroes and villains is neither necessary nor possible, though some of the stories are tragic. In the end, all one can really say about astronomers’ efforts to keep open channels of communication that others wanted to choke off is, “the best we can do is the best we can do.” 1. Introduction astronomy (though some of the practitioners were actually Christian and Jewish) coincided with the largest extents of Astronomy has always been among the most international of regions governed by caliphates and other Moslem empire-like sciences. Some of the reasons are obvious. You cannot observe structures. In addition, Arabic astronomy also drew on earlier the whole sky continuously from any one place. Attempts to Greek, Persian, and Indian writings. measure geocentric parallax and to observe solar eclipses have In contrast, the Europe of the 16th century, across which required going to the ends (or anyhow the middles) of the earth. -

William A. Fowler Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2d5nb7kj No online items Guide to the Papers of William A. Fowler, 1917-1994 Processed by Nurit Lifshitz, assisted by Charlotte Erwin, Laurence Dupray, Carlo Cossu and Jennifer Stine. Archives California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Blvd. Mail Code 015A-74 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: (626) 395-2704 Fax: (626) 793-8756 Email: [email protected] URL: http://archives.caltech.edu © 2003 California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Guide to the Papers of William A. Consult repository 1 Fowler, 1917-1994 Guide to the Papers of William A. Fowler, 1917-1994 Collection number: Consult repository Archives California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California Contact Information: Archives California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Blvd. Mail Code 015A-74 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: (626) 395-2704 Fax: (626) 793-8756 Email: [email protected] URL: http://archives.caltech.edu Processed by: Nurit Lifshitz, assisted by Charlotte Erwin, Laurence Dupray, Carlo Cossu and Jennifer Stine Date Completed: June 2000 Encoded by: Francisco J. Medina. Derived from XML/EAD encoded file by the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics as part of a collaborative project (1999) supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. © 2003 California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: William A. Fowler papers, Date (inclusive): 1917-1994 Collection number: Consult repository Creator: Fowler, William A., 1911-1995 Extent: 94 linear feet Repository: California Institute of Technology. Archives. Pasadena, California 91125 Abstract: These papers document the career of William A. Fowler, who served on the physics faculty at California Institute of Technology from 1939 until 1982. -

Generated on 2012-08-23 18:24 GMT

1SS5 mtt TEGfiNIG. OLD SERIES, NO. II. NEW SERIES, NO. 8. University of Michigan Engineering Society. ALEX. M. HAUBRICH, HEMAN BURR LEONARD, Managing Editor. Business Manager. THOMAS DURAND McCOLL, HOMER WILSON WYCKOFF, CHARLES HENRY SPENCER. THE DETROIT OBSERVATORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. ASAPH HALL, JR., PH.D. This Observatory was built about 1854 through the efforts of Presi- dent Tappan, money for the purpose being raised in Detroit. Mr. Henry N. Walker of Detroit was especially interested in the project and gave funds for the purchase of a meridian circle. The Observatory building is of the usual old-fashioned type, a cen- tral part on the top of which is the dome for the equatorial, and eaBt and west wings, the meridian circle being in the east wing and the library in the west. All the walls are of heavy masonry. About 1853 Dr. Tappan visited Europe and consulted Encke, direc- tor of the Berlin Observatory and Professor of Astronomy in the Uni- versity of Berlin, with regard to the Ann Arbor Observatory. By his advice a meridian circle was ordered of Pistor and Martins and a clock of Tiede. At this time Francis Brunnow was first assistant in the Berlin Obser- vatory. Probably it was through Encke that Brunnow came, in 1854, to- the University of Michigan as the first Professor of Astronomy and. Generated on 2012-08-23 18:24 GMT / http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015071371267 Open Access, Google-digitized / http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#oa-google 10 Thk Technic. Director of the Observatory. 1 think it likely that the 12} inch Fitz equatorial was ordered before his coming; but it was not delivered till after he was on the ground. -

Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science

Springer Biographies Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science RICHARD TAIBI Springer Biographies More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13617 Richard Taibi Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science 123 Richard Taibi Temple Hills, MD USA ISSN 2365-0613 ISSN 2365-0621 (electronic) Springer Biographies ISBN 978-3-319-44517-5 ISBN 978-3-319-44518-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44518-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016949123 © Richard Taibi 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 2006 New Documents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 2006 New Documents Published in Special Issue of Journal of the Antique Telescope Society Reveal Unknown Aspects of Early Career of Major American Telescope-Maker Alvan Clark More than two dozen documents previously unknown to historians shed new light on the early struggles of the nineteenth-century American telescope-maker Alvan Clark to establish his reputation for his astronomical expertise and optical skill. The documents, ranging from manuscript letters and notes to letters to newspaper editors—have been made public for the first time in the Summer/Fall 2006 issue of the Journal of the Antique Telescope Society, published this month as a single-topic double-length issue devoted to Clark’s early telescope-making efforts. “This special Alvan Clark issue of the Journal of the Antique Telescope Society is the most significant publica- tion of new material about Alvan Clark since 1995,” declared the Antique Telescope Society’s president, Dr. Mi- chael Reynolds, F.R.A.S., associate dean of mathematics and natural sciences and professor of astronomy at Florida Community College in Jacksonville, and executive director emeritus of the Chabot Space and Science Center in Oakland, California. (In 1995, Deborah Jean Warner and Robert B. Ariail published their now-classic biography and catalogue Alvan Clark & Sons: Artists in Optics [second edition, Richmond, Va.: Willmann–Bell, in association with the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution].) Alvan Clark (1804-1887) was the United States’s -

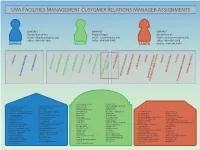

Uva Facilities Management Customer Relations Manager Assignments

UVA FACILITIES MANAGEMENT CUSTOMER RELATIONS MANAGER ASSIGNMENTS CONTACT CONTACT CONTACT Dennis Bianchetto Reggie Steppe Sarita Herman email - [email protected] email - [email protected] email - [email protected] oce - 434-243-1092 oce - 434-243-2442 oce - 434-924-1958 DENNIS REGGIE SARITA mobile - 434-981-0647 LIBRARY FINANCE IT VP/CIO PROVOST ATHLETICS CURRY SCHOOL ARTS GROUNDS BATTEN SCHOOL SCIENCES STUDENT AFFAIRS MCINTIRE SCHOOL EXECUTIVE VP/COO HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT & UR PRESIDENT’S OFFICE RES & PUBLIC SERVICE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND ENGINEERING SCHOOL BUSINESS OPERATIONS DIVERSITY AND EQUITY ARCHITECTURE SCHOOL SCHOOL OF CONTINUING VP MANAGEMENT & BUDGET AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES ASTRONOMY BUILDING KERCHOF HALL AQUATIC & FITNESS CENTER NORTH GROUNDS RECREATION CTR BAYLY BUILDING LORNA SUNDBERG INT’L CTR ARENA PARKING GARAGE OHILL DINING FACILITY BEMISS HOUSE MADISON HALL BASEBALL STADIUM ONESTY HALL BIOLOGY GREENHOUSE MAURY HALL BOOKSTORE/CENTRAL GROUNDS PRKG OUTDOOR RECREATION CENTER BOOKER HOUSE MCCORMICK OBSERVATORY 2200 OLD IVY ROAD LAMBETH HOUSE CARR'S HILL FIELD SUPPORT FACILITY PARKING & TRANSIT BROOKS HALL MINOR HALL 315 OLD IVY WAY MADISON HOUSE CHILD CARE CENTER PAVILION VII/COLONNADE CLUB BRYAN HALL MONROE HALL 350 OLD IVY WAY MATERIALS SCIENCE CULBRETH ROAD GARAGE PRINTING SERVICE CENTER CARR’S HILL NEW CABELL HALL AEROSPACE RESEARCH LABORATORY MECHANICAL ENGINEERING EMMET/IVY GARAGE RUNK DINING HALL CHEMISTRY BUILDING OLD CABELL HALL ALBERT H SMALL BUILDING MICHIE BUILDINGS ERN COMMONS SCOTT STADIUM CLARK HALL PEABODY HALL ALDERMAN LIBRARY MUSIC LIBRARY - OLD CABELL HALL FONTANA FOOD CENTER SHELBURNE HALL/HIGHWAY RESEARCH COCKE HALL PHYSICAL AND LIFE SCIENCES BAVARO HALL OBSERVATORY MTN ENGINEERING RESEARCH FORESTRY BUILDING GARAGE SLAUGHTER RECREATION CENTER DAWSON'S ROW PHYSICS/J BEAMS LAB BROWN LIBRARY - CLARK HALL OLSSON HALL FRANK C. -

PUBLICATIONS of the ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY of the PACIFIC Vol. 65 December 1953 No. 387 ARMIN OTTO LEUSCHNER 1868-1953 Dinsmore Al

PUBLICATIONS OF THE ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF THE PACIFIC Vol. 65 December 1953 No. 387 ARMIN OTTO LEUSCHNER 1868-1953 Dinsmore Alter Griffith Observatory An account of my own first contacts with Professor Leuschner will be related here because it illustrates such an important aspect of his personality. It is merely one of the many stories which other astronomers could tell of what he did for them. Indeed, there are others that may illustrate even better the efforts he made to help those who studied under him. In December 1913, I was a young professor at the Univer- sity of Alabama, very anxious to finish the requirements for a Ph.D. degree, but, because I had a wife and daughter to consider, I could not afford to accept an ordinary fellowship. I wrote to Dr. Leuschner, to whom I was a stranger, asking about the pos- sibility of a teaching position which would enable me to carry on my graduate studies. In reply, he offered me a fellowship but feared that a full-time instructorship would not be available. I explained my financial position in detail, and later that winter he offered me an instructorship. After my arrival in Berkeley I learned that he had combined two fellowships to make it possible for me to go there. I had been away from formal study for several years, and, moreover, had received very poor instruction in mathematics while an undergraduate at a small college. During my first months at Berkeley I studied long hours because of this handicap. One afternoon Professor Leuschner asked me to take a walk 269 © Astronomical Society of the Pacific · Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System Γ.,?.