Measuring Variable Stars Visually

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sky Notes - April 2012

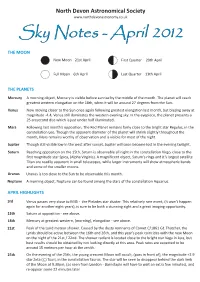

North Devon Astronomical Society www.northdevonastronomy.co.uk Sky Notes - April 2012 THE MOON New Moon 21s t April First Quarter 29th April Full Moon 6th April Last Quarter 13th April THE PLANETS Mercury A morning object, Mercury is visible before sunrise by the middle of the month. The planet will reach greatest western elongation on the 18th, when it will be around 27 degrees from the Sun. Venus Now moving closer to the Sun once again following greatest elongation last month, but blazing away at magnitude -4.4, Venus still dominates the western evening sky. In the eyepiece, the planet presents a 25 arcsecond disc which is just under half illuminated. Mars Following last month’s opposition, The Red Planet remains fairly close to the bright star Regulus, in the constellation Leo. Though the apparent diameter of the planet will shrink slightly throughout the month, Mars remains worthy of observation and is visible for most of the night. Jupiter Though still visible low in the west after sunset, Jupiter will soon become lost in the evening twilight. Saturn R eaching opposition on the 15th, Saturn is observable all night in the constellation Virgo, close to the first magnitude star Spica, (Alpha Virginis). A magnificent object, Saturn’s rings and it’s largest satellite Titan are readily apparent in small telescopes, while larger instruments will show atmospheric bands and some of the smaller moons. Uranus Ur anus is too close to the Sun to be observable this month. Neptune A morning object, Neptune can be found among the stars of the constellation Aquarius. -

Plotting Variable Stars on the H-R Diagram Activity

Pulsating Variable Stars and the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram: The H-R diagram is an important astronomical tool for understanding how stars evolve over time. Stellar evolution can not be studied by observing individual stars as most changes occur over millions and billions of years. Astrophysicists observe numerous stars at various stages in their evolutionary history to determine their changing properties and probable evolutionary tracks across the H-R diagram. The H-R diagram is a scatter graph of stars. When the absolute magnitude (MV) – intrinsic brightness – of stars is plotted against their surface temperature (stellar classification) the stars are not randomly distributed on the graph but are mostly restricted to a few well-defined regions. The stars within the same regions share a common set of characteristics. As the physical characteristics of a star change over its evolutionary history, its position on the H-R diagram The H-R Diagram changes also – so the H-R diagram can also be thought of as a graphical plot of stellar evolution. From the location of a star on the diagram, its luminosity, spectral type, color, temperature, mass, age, chemical composition and evolutionary history are known. Most stars are classified by surface temperature (spectral type) from hottest to coolest as follows: O B A F G K M. These categories are further subdivided into subclasses from hottest (0) to coolest (9). The hottest B stars are B0 and the coolest are B9, followed by spectral type A0. Each major spectral classification is characterized by its own unique spectra. -

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

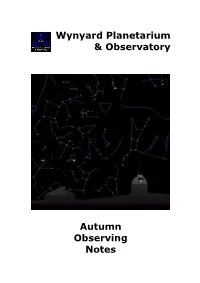

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science Corresponding Authors Lucianne M. Walkowicz Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley [email protected] phone: (510) 642–6931 Andrew C. Becker Department of Astronomy, University of Washington [email protected] phone: (206) 685–0542 Authors Scott F. Anderson, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Joshua S. Bloom, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Leonid Georgiev, Universidad Autonoma de Mexico Josh Grindlay, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Steve Howell, National Optical Astronomy Observatory Knox Long, Space Telescope Science Institute Anjum Mukadam, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Andrej Prsa,ˇ Villanova University Joshua Pepper, Villanova University Arne Rau, California Institute of Technology Branimir Sesar, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nicole Silvestri, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nathan Smith, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Keivan Stassun, Vanderbilt University Paula Szkody, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Science Frontier Panels: Stars and Stellar Evolution (SSE) February 16, 2009 Abstract The next decade of survey astronomy has the potential to transform our knowledge of variable stars. Stellar variability underpins our knowledge of the cosmological distance ladder, and provides direct tests of stellar formation and evolution theory. Variable stars can also be used to probe the fundamental physics of gravity and degenerate material in ways that are otherwise impossible in the laboratory. The computational and engineering advances of the past decade have made large–scale, time–domain surveys an immediate reality. Some surveys proposed for the next decade promise to gather more data than in the prior cumulative history of astronomy. -

Spectroscopy of Variable Stars

Spectroscopy of Variable Stars Steve B. Howell and Travis A. Rector The National Optical Astronomy Observatory 950 N. Cherry Ave. Tucson, AZ 85719 USA Introduction A Note from the Authors The goal of this project is to determine the physical characteristics of variable stars (e.g., temperature, radius and luminosity) by analyzing spectra and photometric observations that span several years. The project was originally developed as a The 2.1-meter telescope and research project for teachers participating in the NOAO TLRBSE program. Coudé Feed spectrograph at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Ari- Please note that it is assumed that the instructor and students are familiar with the zona. The 2.1-meter telescope is concepts of photometry and spectroscopy as it is used in astronomy, as well as inside the white dome. The Coudé stellar classification and stellar evolution. This document is an incomplete source Feed spectrograph is in the right of information on these topics, so further study is encouraged. In particular, the half of the building. It also uses “Stellar Spectroscopy” document will be useful for learning how to analyze the the white tower on the right. spectrum of a star. Prerequisites To be able to do this research project, students should have a basic understanding of the following concepts: • Spectroscopy and photometry in astronomy • Stellar evolution • Stellar classification • Inverse-square law and Stefan’s law The control room for the Coudé Description of the Data Feed spectrograph. The spec- trograph is operated by the two The spectra used in this project were obtained with the Coudé Feed telescopes computers on the left. -

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves An AAVSO course for the Carolyn Hurless Online Institute for Continuing Education in Astronomy (CHOICE) This is copyrighted material meant only for official enrollees in this online course. Do not share this document with others. Please do not quote from it without prior permission from the AAVSO. Table of Contents Course Description and Requirements for Completion Chapter One- 1. Introduction . What are variable stars? . The first known variable stars 2. Variable Star Names . Constellation names . Greek letters (Bayer letters) . GCVS naming scheme . Other naming conventions . Naming variable star types 3. The Main Types of variability Extrinsic . Eclipsing . Rotating . Microlensing Intrinsic . Pulsating . Eruptive . Cataclysmic . X-Ray 4. The Variability Tree Chapter Two- 1. Rotating Variables . The Sun . BY Dra stars . RS CVn stars . Rotating ellipsoidal variables 2. Eclipsing Variables . EA . EB . EW . EP . Roche Lobes 1 Chapter Three- 1. Pulsating Variables . Classical Cepheids . Type II Cepheids . RV Tau stars . Delta Sct stars . RR Lyr stars . Miras . Semi-regular stars 2. Eruptive Variables . Young Stellar Objects . T Tau stars . FUOrs . EXOrs . UXOrs . UV Cet stars . Gamma Cas stars . S Dor stars . R CrB stars Chapter Four- 1. Cataclysmic Variables . Dwarf Novae . Novae . Recurrent Novae . Magnetic CVs . Symbiotic Variables . Supernovae 2. Other Variables . Gamma-Ray Bursters . Active Galactic Nuclei 2 Course Description and Requirements for Completion This course is an overview of the types of variable stars most commonly observed by AAVSO observers. We discuss the physical processes behind what makes each type variable and how this is demonstrated in their light curves. Variable star names and nomenclature are placed in a historical context to aid in understanding today’s classification scheme. -

Discovery of a Wolf–Rayet Star Through Detection of Its Photometric Variability

The Astronomical Journal, 143:136 (6pp), 2012 June doi:10.1088/0004-6256/143/6/136 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. DISCOVERY OF A WOLF–RAYET STAR THROUGH DETECTION OF ITS PHOTOMETRIC VARIABILITY Colin Littlefield1, Peter Garnavich2, G. H. “Howie” Marion3,Jozsef´ Vinko´ 4,5, Colin McClelland2, Terrence Rettig2, and J. Craig Wheeler5 1 Law School, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA 2 Physics Department, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA 3 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 4 Department of Optics, University of Szeged, Hungary 5 Astronomy Department, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712, USA Received 2011 November 9; accepted 2012 April 4; published 2012 May 2 ABSTRACT We report the serendipitous discovery of a heavily reddened Wolf–Rayet star that we name WR 142b. While photometrically monitoring a cataclysmic variable, we detected weak variability in a nearby field star. Low- resolution spectroscopy revealed a strong emission line at 7100 Å, suggesting an unusual object and prompting further study. A spectrum taken with the Hobby–Eberly Telescope confirms strong He ii emission and an N iv 7112 Å line consistent with a nitrogen-rich Wolf–Rayet star of spectral class WN6. Analysis of the He ii line strengths reveals no detectable hydrogen in WR 142b. A blue-sensitive spectrum obtained with the Large Binocular Telescope shows no evidence for a hot companion star. The continuum shape and emission line ratios imply a reddening of E(B − V ) = 2.2–2.6 mag. -

134, December 2007

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 134, December 2007 Contents AB Andromedae Primary Minima ......................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................. 1 Recurrent Objects Programme and Long Term Polar Programme News............4 Eclipsing Binary News ..................................................................................... 5 Chart News ...................................................................................................... 7 CE Lyncis ......................................................................................................... 9 New Chart for CE and SV Lyncis ........................................................ 10 SV Lyncis Light Curves 1971-2007 ............................................................... 11 An Introduction to Measuring Variable Stars using a CCD Camera..............13 Cataclysmic Variables-Some Recent Experiences ........................................... 16 The UK Virtual Observatory ......................................................................... 18 A New Infrared Variable in Scutum ................................................................ 22 The Life and Times of Charles Frederick Butterworth, FRAS........................24 A Hard Day’s Night: Day-to-Day Photometry of Vega and Beta Lyrae.........28 Delta Cephei, 2007 ......................................................................................... 33 -

Gaia Data Release 2 Special Issue

A&A 623, A110 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833304 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Gaia Data Release 2 Special issue Gaia Data Release 2 Variable stars in the colour-absolute magnitude diagram?,?? Gaia Collaboration, L. Eyer1, L. Rimoldini2, M. Audard1, R. I. Anderson3,1, K. Nienartowicz2, F. Glass1, O. Marchal4, M. Grenon1, N. Mowlavi1, B. Holl1, G. Clementini5, C. Aerts6,7, T. Mazeh8, D. W. Evans9, L. Szabados10, A. G. A. Brown11, A. Vallenari12, T. Prusti13, J. H. J. de Bruijne13, C. Babusiaux4,14, C. A. L. Bailer-Jones15, M. Biermann16, F. Jansen17, C. Jordi18, S. A. Klioner19, U. Lammers20, L. Lindegren21, X. Luri18, F. Mignard22, C. Panem23, D. Pourbaix24,25, S. Randich26, P. Sartoretti4, H. I. Siddiqui27, C. Soubiran28, F. van Leeuwen9, N. A. Walton9, F. Arenou4, U. Bastian16, M. Cropper29, R. Drimmel30, D. Katz4, M. G. Lattanzi30, J. Bakker20, C. Cacciari5, J. Castañeda18, L. Chaoul23, N. Cheek31, F. De Angeli9, C. Fabricius18, R. Guerra20, E. Masana18, R. Messineo32, P. Panuzzo4, J. Portell18, M. Riello9, G. M. Seabroke29, P. Tanga22, F. Thévenin22, G. Gracia-Abril33,16, G. Comoretto27, M. Garcia-Reinaldos20, D. Teyssier27, M. Altmann16,34, R. Andrae15, I. Bellas-Velidis35, K. Benson29, J. Berthier36, R. Blomme37, P. Burgess9, G. Busso9, B. Carry22,36, A. Cellino30, M. Clotet18, O. Creevey22, M. Davidson38, J. De Ridder6, L. Delchambre39, A. Dell’Oro26, C. Ducourant28, J. Fernández-Hernández40, M. Fouesneau15, Y. Frémat37, L. Galluccio22, M. García-Torres41, J. González-Núñez31,42, J. J. González-Vidal18, E. Gosset39,25, L. P. Guy2,43, J.-L. Halbwachs44, N. C. Hambly38, D. -

Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars

Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars As amateur astronomers gain ever-increasing access to professional tools, the science of spectroscopy of variable stars is now within reach of the experienced variable star observer. In this section we shall examine the basic tools used to perform spectroscopy and how to use the data collected in ways that augment our understanding of variable stars. Naturally, this section cannot cover every aspect of this vast subject, and we will concentrate just on the basics of this field so that the observer can come to grips with it. It will be noticed by experienced observers that variable stars often alter their spectral characteristics as they vary in light output. Cepheid variable stars can change from G types to F types during their periods of oscillation, and young variables can change from A to B types or vice versa. Spec troscopy enables observers to monitor these changes if their instrumentation is sensitive enough. However, this is not an easy field of study. It requires patience and dedication and access to resources that most amateurs do not possess. Nevertheless, it is an emerging field, and should the reader wish to get involved with this type of observation know that there are some excellent guides to variable star spectroscopy via the BAA and the AAVSO. Some of the workshops run by Robin Leadbeater of the BAA Variable Star section and others such as Christian Buil are a very good introduction to the field. © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 M. Griffiths, Observer’s Guide to Variable Stars, The Patrick Moore 291 Practical Astronomy Series, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00904-5 292 Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars Spectra, Spectroscopes and Image Acquisition What are spectra, and how are they observed? The spectra we see from stars is the result of the complete output in visible light of the star (in simple terms). -

Star Science in the Autumn Sky by John R

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 32 - Fall 1995 © 1995, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Star Science in the Autumn Sky by John R. Percy, University of Toronto and George Musser, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Be honest: Do the stars all look the same to you? If you look up at the night sky, you can see anything from dozens to thousands of them, depending on where you live. To most people, the stars are just points of light, each one like the other. To astronomers, however, stars are as varied as people. There are as many different kinds of stars in our galaxy as there are people on Earth. They come in all shapes, sizes, colors, and dispositions. And stars, like people, have their life cycles. They are born, grow up, and die (don't pay taxes, though). The study of the stars and their lives, the great People magazine of the skies, is known as astrophysics. Astrophysics sounds imposing. Say the word at a cocktail party and see how fast the conversation grinds to a halt. Star science, which is what astrophysics is, sounds much more friendly. The following activities will introduce you to star science as you ramble across the autumn sky. Though the stars are distant, you can come to understand their nature by making simple observations and drawing analogies to everyday things on Earth. When you can look at a star and see more than a point of light, the night sky will come alive. Activity 1. Finding your way with a star map Activity 2.