Experiences of the Common Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Path, from the Sacred to the Profane in Fermented Beverages in New Galicia, New Spain (Mexico), Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century

The Early Path, from the Sacred to the Profane in Fermented Beverages in New Galicia, New Spain (Mexico), Seventeenth to Eighteenth Century María de la Paz SOLANO PÉREZ The Beginning of the Path: Introduction From an Ethno-historical perspective, the objectives of the present paper are to show changes in perceptions of fermented beverages, as they lost their sacral nature in a good part of the baroque society of New Spain’s Viceroyalty,1 turn- ing into little more than profane beverages in the eye of the law of the Spanish crown for the new American territories, specifically for the Kingdom of New Galicia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, within the New Spain viceroyalty. At the time the newly profane beverages were discredited in urban places, were subject to displacement by distilled beverages, being introduced from both oceans – from the Atlantic by the way of the Metropolis, and from the Pacific through the Manilla Galleon. The new distilled beverages converged in western New Spain, where Guadalajara was the economic, political, religious, and cultural centre. To begin with, it is necessary to stress that the fermentation process has been used for many purposes since ancient times. Most notably, it has been used in medicine, in nutrition, and as part of religion and rituality for most societies around the world. 1 This area, after its independence process in the beginning of the nineteenth century, was known as Mexico. Before this date, it belonged to the Spanish Crown as New Spain, also as part of other territories situated along the American continent. -

CENTROS DE ACOPIO Operador No

CENTROS DE ACOPIO Operador No. Ubicación Corporativo Acento Locales 6 y 7, Av. Jorge Jiménez Cantú 1 S/N, Colonia Hacienda de Valle Escondido, C.P. 52937, Atizapán de Zaragoza, Estado de México. Av. López Mateos No. 4175, Colonia La Giralda, C.P. 45050, Zapopan; Jalisco. ALCATEL 2 ONE TOUCH Blvd. Manuel Ávila Camacho No. 1007 L-5B, Colonia San 3 Lucas Tepetlacalco, Tlalnepantla de Baz, Estado de México. Av. Miguel Ángel de Quevedo No. 1065, Colonia El Rosedal, 4 Delegación Coyoacán, Distrito Federal. Prado Norte No. 320, Colonia Lomas de Chapultepec, 5 Delegación Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal. Eje 1 Norte Mosqueta No. 259, Colonia Local N1-60, 6 Delegación Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal. Presidente Masaryk No. 182, Colonia Polanco, Delegación 7 Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal. Melchor Ocampo No. 193 L-G 25, Colonia Verónica Anzures, 8 Delegación Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal. Blvd. Interlomas No. 5, Colonia San Fernando, Huixquilucan, 9 Estado de México. Av. Vasco de Quiroga No. 3800, Colonia Antigua Mina de 10 Totoloapa, Delegación Cuajimalpa, Distrito Federal. Av. Montevideo (Mezanine) No. 363 L-228, Colonia Lindavista, 11 Delegación Gustavo A. Madero, Distrito Federal. Florencia No. 69, Colonia Juárez, Delegación Cuauhtémoc, IUSACELL 12 Distrito Federal. Plaza Madrid No. 8, Colonia Roma Norte, Delegación 13 Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal. Circuito Arquitectos No. 1, Ciudad Satélite, Naucalpan de 14 Juárez, Estado de México. Circuito Centro Comercial (dentro de Plaza Satélite) No. 2251, 15 Local 422, Ciudad Satélite, Naucalpan de Juárez, Estado de México. Av. Canal de Tezontle No. 1512, Colonia Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, 16 Delegación Iztapalapa, Distrito Federal. División del Norte No. -

Grupo Axo, S.A.P.I. De C.V. Reporte Anual Que Se

GRUPO AXO, S.A.P.I. DE C.V. REPORTE ANUAL QUE SE PRESENTA DE ACUERDO CON LAS DISPOSICIONES DE CARÁCTER GENERAL APLICABLES A LAS EMISORAS DE VALORES Y OTROS PARTICIPANTES DEL MERCADO, POR EL EJERCICIO SOCIAL TERMINADO EL 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2015 Blvd. Manuel Ávila Camacho No. 40 piso 21 Lomas de Chapultepec, Del. Miguel Hidalgo México, D.F. C.P. 11000 CON BASE EN EL PROGRAMA DE CERTIFICADOS BURSATILES DE LARGO PLAZO CON CARÁCTER DE REVOLVENTE CONSTITUIDO POR GRUPO AXO, S.A.P.I. DE C.V., DESCRITO EN EL PROSPECTO DE DICHO PROGRAMA POR UN MONTO TOTAL AUTORIZADO DE HASTA $1,000,000,000.00 (UN MIL MILLONES DE PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL), O SU EQUIVALENTE EN UDIS, SE LLEVÓ A CABO LA PRESENTE OFERTA PUBLICA DE 10,000,000 (DIEZ MILLONES) DE CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES, CON VALOR NOMINAL DE $100.00 (CIEN PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL) CADA UNO, SEGÚN SE DESCRIBE EN EL SUPLEMENTO (E L “SUPLEMENTO”). MONTO TOTAL DE LA OFERTA: $1´000,000,000.00 (UN MIL MILLONES DE PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL) NÚMERO DE CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES: 10’000,000 (DIEZ MILLON ES) DE CER TIFICAD O S BURSÁTILES CLAVE DE PIZARRA: AXO14 Los Certificados Bursátiles se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores y se cotizan en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores. La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad de los valores o la solvencia del emisor o sobre la exactitud o veracidad de la información contenida en el Reporte Anual, ni convalida los actos que, en su caso, hubieran sido realizados en contravención de las leyes. -

Elaboración De Una Bebida Alcohólica Destilada a Partir De Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Miller Procedente Del Distrito De San Bartolomé, Huarochirí-Lima

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE FARMACIA Y BIOQUÍMICA E.A.P. DE FARMACIA Y BIOQUÍMICA Elaboración de una bebida alcohólica destilada a partir de Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller procedente del distrito de San Bartolomé, Huarochirí-Lima TESIS Para optar el Título Profesional de Químico Farmacéutico AUTOR Jon Ramiro Rosendo Lima Clemente ASESOR Gladys Constanza Arias Arroyo Lima - Perú 2017 DEDICATORIA A mis queridos padres, los abogados Rosendo y Elcira, porque mi éxito es resultado de la formación que me dieron. Con cariño a mi hermana Gabriela y demás familiares por compartir conmigo momentos inolvidables. Y a mis mejores amigos por apoyarme en todo momento y acompañarme en mis logros. AGRADECIMIENTOS A la Dra. Gladys Constanza Arias Arroyo por el apoyo brindado para el desarrollo de mi tesis. A mi Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica y profesores, por la formación académica y aportes invaluables, que hicieron posible la realización de este trabajo de investigación. Así también, por la revisión exhaustiva de mi tesis, a los miembros del jurado: Dra. María Elena Salazar Salvatierra, Dra. Yadira Fernandez Jerí, Dr. Robert Dante Almonacid Román y Dr. Nelson Bautista Cruz. RESUMEN Este trabajo tuvo como objetivo la elaboración de una bebida alcohólica destilada utilizando Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller “tuna”, procedente del distrito de San Bartolomé, Huarochirí, Lima – Perú. Del estudio fisicoquímico- bromatológico de la pulpa fresca de la tuna, se obtuvo los siguientes resultados expresados en g % de muestra fresca: 86,0 de humedad; 2,0 de fibra cruda; 0,1 de extracto etéreo; 0,4 de cenizas; 0,5 de proteínas; 11,0 de carbohidratos. -

Noviembre 2016

SUBSECRETARIA DE PROGRAMAS DELEGACIONALES Y REORDENAMIENTO DE LA VÍA PÚBLICA PADRÓN DE ESTABLECIMIENTOS MERCANTILES DELEGACIÓN: CUAUHTÉMOC MES QUE SE REPORTA NOVIEMBRE HORARIO PERMISO PARA VENTA DE BEBIDAS NOMBRE O DENOMINACIÓN DIRECCIÓN FECHA DE APERTURA TIPO DE PERMISO PERMITIDO ALCOHOLICAS HAMBURGUESAS MEMORABLES RIO LERMA 335 Cuauhtémoc 6500 Cuauhtémoc 01/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. JUAN TARRASA DELGADO INDEPENDENCIA 68 LOCAL 1 Centro (Área 5) 6050 Cuauhtémoc 01/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. "REVELES" EJE 2 165 Buenos Aires 6780 Cuauhtémoc 01/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. Hamburguesas Luchita Carlos J. Meneses 216 Loc B Buenavista 6350 Cuauhtémoc 01/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. SERVICIOS INTEGRALES DAKA, S.A DE C.V. ARCOS DE BELÉN 55D Centro (Área 7) 6070 Cuauhtémoc 01/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. FoodDrop Dr. rafael Lucio 102 A 2 Pegaso LOC 2 Doctores 6720 Cuauhtémoc 02/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. FRUTOS PROHIBIDOS Y OTROS PLACERES RÍO LERMA 232 MZ-7 Cuauhtémoc 6500 Cuauhtémoc 02/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. ESTACIONAMIENTO SAN ANTONIO XOCONGO 75 Transito 6820 Cuauhtémoc 02/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. PLAZA HIDALGO DOCTOR ANDRADE 211 B-21 Doctores 6720 Cuauhtémoc 03/11/2016 Bajo Impacto Permanente No tiene permiso por ser de giro de bajo impacto. -

Centros De Atención a Clientes Telcel

Directorio de Centros de Atención a Clientes (CAC) de Telcel en la Ciudad de México ÁREA DE ESPERA POSICIÓN DE ATENCIÓN A SEÑALIZACIÓN ACCESO CON ANIMALES REGIÓN NOMBRE DEL CAC HORARIO Domicilio: Calle Domicilio: No. Exterior Domicilio: No. Interior Domicilio: Colonia Domicilio: Código Postal Domicilio: Municipio Domicilio: Entidad KIOSKO CAJERO ATM RAMPA RUTA ACCESIBLE RESERVADA PARA MENOR ALTURA ACCESIBILIDAD GUIA PERSONAS CON 9 LORETO LUNES A DOMINGO DE 9:00 A 19:00 HRS. ALTAMIRANO 46 PLAZA LORETO TIZAPAN 1090 ÁLVARO OBREGÓN CDMX X X 9 SAN ANGEL LUNES A DOMINGO 10:00 A 19:00 HRS. AVE. INSURGENTES SUR 2105 DENTRO DE TIENDA SANBORNS SAN ANGEL 1000 ÁLVARO OBREGÓN CDMX X X X 9 CAMARONES LUNES A VIERNES 09:00 A 18:00 HRS. CALLE NORTE 77 3331 OBRERO POPULAR 11560 AZCAPOTZALCO CDMX X X X CENTRO COMERCIAL PARQUE 9 PARQUE VÍA VALLEJO LUNES A DOMINGO 10:00 A 20:00 HRS. CALZADA VALLEJO 1090 SANTA CRUZ DE LAS SALINAS 2340 AZCAPOTZALCO CDMX X X X VIA VALLEJO 9 SERVICIO TÉCNICO TELCEL Y CENTRO ATENCIÓN ETRAM ROSARIO LUNES A DOMINGO 10:00 A 20:00 HRS. AVE. DEL ROSARIO 901 CETRAM EL ROSARIO EL ROSARIO 2100 AZCAPOTZALCO CDMX X X X X 9 AMORES LUNES A VIERNES 9:00 A 18:00 HRS. AMORES 26 DEL VALLE 3100 BENITO JUÁREZ CDMX X X X X X X 9 DEL VALLE LUNES A VIERNES 9:00 A 18:00 HRS. EJE 7 SUR FELIX CUEVAS 825 DEL VALLE 3100 BENITO JUÁREZ CDMX X X X X X X 9 EJE CENTRAL LÁZARO CÁRDENAS LUNES A DOMINGO 10:00 A 19:00 HRS. -

Grupo Axo, S.A.P.I. De C.V. Reporte Anual

GRUPO AXO, S.A.P.I. DE C.V. REPORTE ANUAL QUE SE PRESENTA DE ACUERDO CON LAS DISPOSICIONES DE CARÁCTER GENERAL APLICABLES A LAS EMISORAS DE VALORES Y OTROS PARTICIPANTES DEL MERCADO, POR EL EJERCICIO SOCIAL TERMINADO EL 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2016. Blvd. Manuel Ávila Camacho No. 5 Torre C piso 22 Lomas de Sotelo, Municipio Naucalpan de Juárez México, Estado de México C.P. 53390 CON BASE EN EL PROGRAMA DE CERTIFICADOS BURSATILES DE LARGO PLAZO CON CARÁCTER DE REVOLVENTE CONSTITUIDO POR GRUPO AXO, S.A.P.I. DE C.V., DESCRITO EN EL PROSPECTO DE DICHO PROGRAMA POR UN MONTO TOTAL AUTORIZADO DE HASTA $2,500,000,000.00 (DOS MIL QUINIENTOS MILLONES DE PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL), O SU EQUIVALENTE EN UDIS, SE LLEVÓ A CABO LA OFERTA PUBLICA DE 23,400,000 (VEINTITRÉS MILLONES CUATROCIENTOS MIL) CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES, CON VALOR NOMINAL DE $100.00 (CIEN PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL) CADA UNO. MONTO TOTAL DE LA OFERTA: $2´340,000,000.00 (DOS MIL TRESCIENTOS CUARENTA MILLONES DE PESOS 00/100 MONEDA NACIONAL) NÚMERO DE CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES: 23’400,000 (VEINTITRÉS MILLONES CUATROCIENTOS MIL) CERTIFICADOS BURSÁTILES CLAVES DE PIZARRA: AXO14, AXO 16, AXO 16-2 y AXO 17. Los Certificados Bursátiles se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores y se cotizan en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores. La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad de los valores o la solvencia del emisor o sobre la exactitud o veracidad de la información contenida en el Reporte Anual, ni convalida los actos que, en su caso, hubieran sido realizados en contravención de las leyes. -

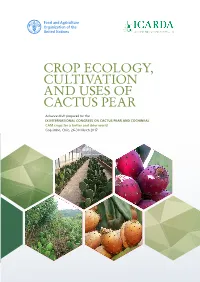

Crop Ecology, Cultivation and Uses of Cactus Pear

CROP ECOLOGY, CULTIVATION AND USES OF CACTUS PEAR Advance draft prepared for the IX INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON CACTUS PEAR AND COCHINEAL CAM crops for a hotter and drier world Coquimbo, Chile, 26-30 March 2017 CROP ECOLOGY, CULTIVATION AND USES OF CACTUS PEAR Editorial team Prof. Paolo Inglese, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Italy; General Coordinator Of the Cactusnet Dr. Candelario Mondragon, INIFAP, Mexico Dr. Ali Nefzaoui, ICARDA, Tunisia Prof. Carmen Sáenz, Universidad de Chile, Chile Coordination team Makiko Taguchi, FAO Harinder Makkar, FAO Mounir Louhaichi, ICARDA Editorial support Ruth Duffy Book design and layout Davide Moretti, Art&Design − Rome Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas Rome, 2017 The designations employed and the FAO encourages the use, reproduction and presentation of material in this information dissemination of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any product. Except where otherwise indicated, opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food material may be copied, downloaded and Agriculture Organization of the United and printed for private study, research Nations (FAO), or of the International Center and teaching purposes, or for use in non- for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas commercial products or services, provided (ICARDA) concerning the legal or development that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO status of any country, territory, city or area as the source and copyright holder is given or of its authorities, or concerning the and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Emisión de Certificados Bursátiles GPH 19 | GPH 19-2 Presentación a Inversionistas Septiembre 2019 Aviso Legal Esta presentación fue preparada por Grupo Palacio de Hierro, S.A.B. de C.V. (“la Compañía”), exclusivamente para el uso establecido en la misma. Esta presentación fue preparada exclusivamente con propósitos informativos y no constituye compromiso alguno de compra o venta de instrumentos o activos financieros. No se contemplan representaciones o garantías expresas o implícitas para la precisión, afinación o integridad de la información presentada o contenida en esta presentación. La Compañía, ni sus afiliadas, consejeros o representantes o cualquiera de sus respectivos colaboradores acepta cualquier responsabilidad en lo que concierne a cualquier pérdida o daño resultante de cualquier información presentada o incluida en esta presentación. La información presentada o incluida en esta presentación es vigente a la fecha y está sujeta a cambios sin la obligación de la compañía de hacer notificaciones y su precisión no está garantizada. La Compañía, ni sus afiliadas, consejeros o representantes harán ningún esfuerzo para actualizar dicha información en lo sucesivo. Esta presentación no involucra temas legales, fiscales, financieros o de ningún otro tipo. Cierta información en esta presentación fue obtenida de diversas fuentes y la Compañía no verificó dicha información con fuentes independientes. Cierta información fue basada también en estimaciones de la Compañía. De acuerdo con esto, la Compañía no responde de la precisión o integridad de esa información o de las estimaciones de la Compañía y dicha información y estimados involucran riesgos e incertidumbre y son sujetos de cambio basados en factores varios. 2 Presentadores . -

Establecimientos Que Cuentan Con Distintivo "H" Vigentes En El Estado De Aguascalientes

ESTABLECIMIENTOS QUE CUENTAN CON DISTINTIVO "H" VIGENTES EN EL ESTADO DE AGUASCALIENTES No. de CORREO ESTABLECIMIENTO STATUS DIA MES AÑO DEL/MPIO. Distintivo ELECTRÓNICO 91 Hotel Fiesta Inn Aguascalientes Lobby Bar vigente 4 Diciembre 2015 Aguascalientes [email protected] 96 Fiesta Americana Aguascalientes Restaurante La Fronda vigente 18 Febrero 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 771 Estancia de Bienestar Infantil EBI-ISSSSPEA. Comedor Infantil. vigente 9 Septiembre 2015 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1239 Comedor Industrial NISSAN Mexicana Aguascalientes (Carrocerías), Operado por Comida de Aguascalientes, S.A. de C.V. vigente 3 Junio 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1361 YAK Aguascalientes vigente 26 Noviembre 2015 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1505 Fiesta Americana Aguascalientes Comedor de Colaboradores San Marcos vigente 18 Febrero 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1506 Fiesta Americana Aguascalientes Bar Antioquía vigente 18 Febrero 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1846 Comedor Industrial NISSAN Mexicana Aguascalientes (Motor) Operado por Comida de Aguascalientes, S.A. de C.V. vigente 4 Junio 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1847 Comedor Industrial NISSAN Mexicana Aguascalientes (Plásticos) Operado por Comida de Aguascalientes, S.A. de C.V.. vigente 4 Junio 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 1888 Comedor Industrial NISSAN Mexicana Aguascalientes (Ensamble) Operado por Comida de Aguascalientes S.A. de C.V. vigente 4 Junio 2016 Aguascalientes [email protected] 2276 Comedor de Colaboradores de Frigorizados La Huerta S.A. de C.V. vigente 29 Septiembre 2015 San Francisco de los Romo [email protected] 2677 Comedor Industrial de Unipres Mexicana, S.A. -

Reconfiguración Del Territorio En La Colonia Guerrero a Partir De Proyectos Urbano-Arquitectónicos 1873-2016

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Programa de maestría y doctorado en arquitectura Campo de Conocimiento. Arquitectura, Ciudad y Territorio Reconfiguración del territorio en la Colonia Guerrero a partir de proyectos urbano-arquitectónicos 1873-2016 TESIS Que para optar por el grado de: Maestra en Arquitectura PRESENTA LOPEZ HUIDOBRO Pilar Tutor de Tesis: Dr. José Ángel Campos Salgado. Sinodales: Arq. Alejandro Suarez Pareyón. Mtro.Alejandro Cabeza Pérez Mtro Eduardo Torres Veytia. Mtra. Elena Tudela Rivadaneyra. Facultad de Arquitectura Ciudad Universitaria, México. junio 2018 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Programa de maestría y doctorado en arquitectura Campo de Conocimiento. Arquitectura, Ciudad y Territorio Reconfiguración del territorio en la colonia Guerrero a partir de proyectos urbano-arquitectónicos 1873-2016 TESIS Que para optar por el grado de: Maestra en Arquitectura PRESENTA López Huidobro Pilar Tutor de Tesis: Dr. José Ángel Campos Salgado. Sinodales: Arq. Alejandro Suarez Pareyón. Mtro.Alejandro Cabeza Pérez Mtro Eduardo Torres Veytia. Mtra. Elena Tudela Rivadaneyra. -

Sucursales Devlyn Abiertas De Lunes a Domingo De 12:00 a 19:00 Hrs

SUCURSALES DEVLYN ABIERTAS DE LUNES A DOMINGO DE 12:00 A 19:00 HRS. CDMX Y ZONA METROPOLITANA SEMÁFORO NARANJA DE CONTINGENCIA AMBIENTAL NOMBRE FORMATO DELEGACIÓN/MUNICIPIO Estado C.P CERVANTES SAAVEDRA DEVLYN MIGUEL HIDALGO Ciudad de México 11520 PABELLON BOSQUES DEVLYN MIGUEL HIDALGO Ciudad de México 65100 DEVLYN PABELLON POLANCO DEVLYN MIGUEL HIDALGO Ciudad de México 11510 GRAN PATIO SANTA FE DEVLYN ALVARO OBREGON Ciudad de México 11250 DEVLYN CHEDRAUI POLANCO DEVLYN MIGUEL HIDALGO Ciudad de México 11570 GALERIAS MARINA DEVLYN CUAUHTEMOC Ciudad de México 11300 CHEDRAUI EDUARDO MOLINA DEVLYN GUSTAVO A. MADERO Ciudad de México 7420 WALMART AZCAPOTZALCO WALMART AZCAPOTZALCO Ciudad de México 2770 WAL MART EDUARDO MOLINA WALMART GUSTAVO A. MADERO Ciudad de México 7090 PLAZA LINDAVISTA DEVLYN GUSTAVO A. MADERO Ciudad de México 7300 PARQUE LINDAVISTA DEVLYN GUSTAVO A. MADERO Ciudad de México 77600 PLAZA TORRES LINDAVISTA DEVLYN GUSTAVO A. MADERO Ciudad de México 7320 DEVLYN CHEDRAUI (TENAYUCA) DEVLYN TLALNEPANTLA DE BAZ Ciudad de México 7640 CHEDRAUI EL ANFORA DEVLYN VENUSTIANO CARRANZA Ciudad de México 15360 PLAZA AZCAPOTZALCO DEVLYN AZCAPOTZALCO Ciudad de México 2000 PATIO CLAVERIA DEVLYN AZCAPOTZALCO Ciudad de México 2080 PLAZA ORIENTE DEVLYN Iztapalapa Ciudad de México 9020 PASAJE EJE CENTRAL MADERO 1 DEVLYN CUAUHTEMOC Ciudad de México 06000 FORUM BUENAVISTA DEVLYN CUAUHTEMOC Ciudad de México 6350 BODEGA AURRERA TULYEHUALCO DEVLYN XOCHIMILCO Ciudad de México 9880 PORTAL CENTRO (PATIO BOUTIRINI) DEVLYN CUAUHTEMOC Ciudad de México x WAL