Curating Liveness: the Role of Youtube in Constructing Authentic Viewing Experiences Through Live Music Channels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GG 050219.Pdf

GREENPOINT | WILLIAMSBURG & BUSHWICK Since 1974 Since VOLUME 47 | NUMBER 17 MAY 2, 2019 (718) 422-7400 25¢ Brooklyn Eagle Group Study: Williamsburg, Bushwick had the most alcohol-related emergency room visits in Brooklyn Greenpoint is full of bars with outdoor seating — but there won’t be many outdoor ads for booze anymore. An order from Mayor Bill de Blasio, which takes effect immediately, bans any alcohol-related ads on bus shelters, newsstands, phone booths, LinkNYC kiosks and recycling containers. See page 2. Greenpoint Gazette file photo by Lore Croghan Barges and breweries: Sofar Sounds hosts secret concerts in B’klyn’s most unique locations By Scott Enman Frustrated with issues plaguing larger events Greenpoint Gazette — like deafening music and disruptive crowds on their cellphones — founder Rafe Offer set out to From the top of a ski jump in Norway to change the stigma surrounding concerts. the highest floor of the Willis Tower in “A big component of Sofar is discovering Chicago, concert series Sofar Sounds is re- artists, but the other component is discovering defining live music events with secret per- places and discovering the city a little bit bet- formances in offbeat locations. ter,” Sofar New York City Director Stephanie What started as a group of friends hosting Mitchell told the Greenpoint Gazette. parties in their living rooms in London has “These are spaces that people often don’t grown into an international following with think they’re going to experience music in, and events in more than 350 cities. we really love to celebrate those moments where Sofar’s intimate gigs are held in both res- we’re able to work in really unique spaces.” idential and commercial settings, and Brook- The series started in London in 2009, and lyn’s unique urban makeup of waterfront began regularly hosting events in New York in warehouses, factories and industrial buildings 2011. -

Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point February 2019 for Private Circulation Only

Audio OTT economy in India – Inflection point February 2019 For Private circulation only Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Contents Foreword by IMI 4 Foreword by Deloitte 5 Overview - Global recorded music industry 6 Overview - Indian recorded music industry 8 Flow of rights and revenue within the value chain 10 Overview of the audio OTT industry 16 Drivers of the audio OTT industry in India 20 Business models within the audio OTT industry 22 Audio OTT pie within digital revenues in India 26 Key trends emerging from the global recorded music market and their implications for the Indian recorded music market 28 US case study: Transition from physical to downloading to streaming 29 Latin America case study: Local artists going global 32 Diminishing boundaries of language and region 33 Parallels with K-pop 33 China case study: Curbing piracy to create large audio OTT entities 36 Investments & Valuations in audio OTT 40 Way forward for the Indian recorded music industry 42 Restricting Piracy 42 Audio OTT boosts the regional industry 43 Audio OTT audience moves towards paid streaming 44 Unlocking social media and blogs for music 45 Challenges faced by the Indian recorded music industry 46 Curbing piracy 46 Creating a free market 47 Glossary 48 Special Thanks 49 Acknowledgements 49 03 Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Foreword by IMI “All the world's a stage”– Shakespeare, • Global practices via free market also referenced in a song by Elvis Presley, economics, revenue distribution, then sounded like a utopian dream monitoring, and reducing the value gap until 'Despacito' took the world by with owners of content getting a fair storm. -

White+Paper+Music+10.Pdf

In partnership with COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This white paper is written for you. Wherever you live, whatever you do, music is a tool to create connections, develop relationships and make the world a little bit smaller. We hope you use this as a tool to recognise the value in bringing music and tourism together. Copyright: © 2018, Sound Diplomacy and ProColombia Music is the New Gastronomy: White Paper on Music and Tourism – Your Guide to Connecting Music and Tourism, and Making the Most Out of It Printed in Colombia. Published by ProColombia. First printing: November 2018 All rights reserved. No reproduction or copying of this work is permitted without written consent of the authors. With the kind support of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the UNWTO or its members. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Tourism Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Address Sound Diplomacy Mindspace Aldgate, 114 Whitechapel High St, London E1 7PT Address ProColombia Calle 28 # 13a - 15, piso 35 - 36 Bogotá, Colombia 2 In partnership with CONTENT MESSAGE SECRETARY-GENERAL, UNWTO FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCING MUSIC TOURISM 1.1. Why Music? 1.2. Music as a Means of Communication 1.3. Introducing the Music and Tourism Industries 1.3.1. -

Project2 Favartisit Aaiyanajuarez Copy

BILLIE EILISH 2001 American singer-songwriter, Billie Eilish, was born in Los Angeles, California on December 18th. Eilish began writing LATE 2015 songs at the age of 11. In October, she recorded her first song Ocean Eyes. It was later released on Sound Cloud on November 18th. Becoming one her most popular songs. MID 2016 On March 24th, the music video for Ocean Eyes was released on Youtube. Her second single Six Feet Under LATE 2016 was released in June. On November 18th, Ocean Eyes was released worldwide through Darkroom and Interscope Records. EARLY 2017 In January, an EP with four remixes of Ocean Eyes was released. The song Bellyache was released on February 24th, followed by the music video in March. A few days later, Bored was released as part of the MID 2017 soundtrack for Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. In the summer, Eilish released Watch and COPYCAT. Along with the announcement for her debut EP, Don’t Smile at Me. Releasing new singles each Friday in July such as idontwannabeyouanymore and My Boy. LATE 2017 The Don’t Smile at Me EP was released on August 11th. Later, Eilish collaborated with American rapper Vince Staples for a remix of Watch titled &Burn. In September, Apple Music named Eilish an Up Next EARLY 2018 artist due to her albums’ commercial success. In February, Eilish embarked on the WHERE’S MY MIND Tour, which concluded in April. Also in April, she collaborated with American singer Khalid for the single Lovely. The song was part of the soundtrack for the second season of Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. -

Winter Is Coming By: Alex Ziegelbauer and Leo Griesemer

News Sports Pop Culture Comics & Memes H ome Page: November 20th, 2019 Written and Edited by Slinger Middle School Students N ews Winter is Coming By: Alex Ziegelbauer and Leo Griesemer Winter is coming too fast. Snow has already been falling often, and it's not even December! Here are some things you can do while waiting for December to come around. This includes snowboarding, hockey or ice skating, and other snow-related activities. First, you can go snowboarding about anywhere there's snow and a hill. If you want a specific place to go, Little Switz in Slinger is a great location. There are many hills to ride ranging from an easy difficulty to a harder difficulty. There are rails, jumps, and much more, so head down to Little Switz, rent a board and start riding. Also, there’s hockey or ice skating if the ice on a lake is 4 to 6 inches thick. Do not skate or walk on ice that is three inches thick or less. This can be unsafe, and you could get seriously injured. If you don't live near a pond, you can go to a public ice rink with your friends and family. If you do have a pond, an activity is hockey. You just need a goal which you can make out of PVC pipes from a hardware store. This is fun with friends and family, too. Snow-related activities are for you if you don’t want to spend money. You could invite your friends over and do these activities. -

Impact of Islamophobia

QCC Students on the Election (p.6) “Hamlet” arrives at Volume XIX. No. 99 October 2016 QCC (p.13) Impact of Islamophobia BY Nikita Jones and the lives of Muslim youths in the US. Henry Murray award from the Society for like they lived in two different worlds. Some This event was originally scheduled to be Personality and Social Psychology of the showed that they were stuck in the middle, held in the LB-14, but it was relocated to the APA. they felt like they went from being accepted M-136 because of the extremely large group The event started off with Dr. Fine to being discriminated against. Dr. Fine said of diverse and eager students along with a talking about a study that she did with her that the stories reminded her of the Japanese few faculty members, who were ready to colleague Selcuk Sirin in New Jersey, to find concentration camps for Americans, “in hear what Dr. Fine had to say out from young U.S. Muslims, “how they some ways this is what has happened to Dr. Fine is a professor in the Ph.D. experienced being “exiled” from the moral Muslim American kids in the US they were program in psychology at the CUNY community of the U.S. where they had a part of the community and then exiled.” Graduate Center Her main focus is on grown up.” The research was participatory In the study it showed that 61 percent social injustice of any kind. She studies research, where victims of Islamophobia of these youths said that they experienced social injustice in prisons, with the formerly did the research. -

Civic Alliance 2020 Impact Report

civic alliance 2020 impact report 1 civic alliance 2021 1,043 member companies the why: 71% of Americans agree 5,163,938 that CEOs are responsible for being leaders in their organizations and in employees across all American society.* 50 states 68% of Americans believe that as corporate leaders, CEOs are best positioned to drive real change in 160 million America.* voters - the most in U.S. history ≥68% of U.S. adults say a company’s treatment of employees, customers, and society more broadly plays an important role in their purchasing decisions.* *source - The Morning Consult 2 civic alliance 2021 v welcome With 2020 in our rearview mirror, we can truly say “what a year” with every tone, emphasis, and meaning imaginable. But with the benefit of hindsight, we can also say, “what a thing we did together.” The 2020 election saw historic voter turnout, and the election cycle of 2020 saw historic civic engagement. While the country is still writing the story that was this monumental and transformative election, we know that business leaders played a crucial role in promoting and protecting democracy. This Civic Alliance impact report was created to both highlight the community of leaders who came together to face new and unprecedented challenges and to show the power of what we are capable of accomplishing together. We are honored to be in this work with you. Natalie Tran Mike Ward Steven Levine Co-Founder, Civic Alliance Co-Founder, Civic Alliance Director, Civic Alliance Executive Director, VP Voter Engagement, Co-Founder, Meteorite CAA Foundation Democracy Works 3 civic alliance 2021 background who are we? Launched in January 2020 by the CAA Foundation and Democracy Works, the Civic Alliance is the why: a nonpartisan coalition of companies that We believe a strong democracy is good strengthens our democracy by encouraging civic for business and an participation and supporting safe, accessible, engaged business community is good for and trusted elections. -

2019 Providence Results

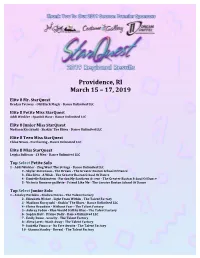

Providence, RI March 15 – 17, 2019 Elite 8 Mr. StarQuest Bradyn Pettway - Old Black MaGic - Dance Unlimited LLC Elite 8 Petite Miss StarQuest Addi Winkler - Spanish Rose - Dance Unlimited LLC Elite 8 Junior Miss StarQuest Madison Kuczynski - Shakin' The Blues - Dance Unlimited LLC Elite 8 Teen Miss StarQuest Chloe Nixon - Everlasting - Dance Unlimited LLC Elite 8 Miss StarQuest Leigha Sullivan - 13 Men - Dance Unlimited LLC Top Select Petite Solo 1 - Addi Winkler - Zing Went The Strings - Dance Unlimited LLC 2 - Skylar Stevenson - The Dream - The Greater Boston School Of Dance 3 - Elia Silva - A Wish - The Greater Boston School Of Dance 4 - Danielle Rubinstein - Pardon My Southern Accent - The Greater Boston School Of Dance 5 - Victoria Romero-guillette - Friend Like Me - The Greater Boston School Of Dance Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Ainsley Pavlakis - Broken Pieces - The Talent Factory 2 - Elizabeth Weber - Light From Within - The Talent Factory 3 - Madison Kuczynski - Shakin' The Blues - Dance Unlimited LLC 4 - Eloise Beaudoin - Without Fear - The Talent Factory 5 - Aubrey Feden - Blue Would Still Be Blue - The Talent Factory 6 - Sophia Holt - Divine Dolly - Dance Unlimited LLC 7 - Emily Rowe - Gravity - The Talent Factory 8 - Alexa Jaret - Wash Away - The Talent Factory 9 - Isabella Vinacco - No Fate Awaits - The Talent Factory 10 - Gianna Stanley - Reveal - The Talent Factory Top Select Teen Solo 1 - Liana Weisbord - Fallin - The Talent Factory 2 - Ellie Stevenson - Safe Now - The Greater Boston School Of Dance 3 - Chloe Nixon - Everlasting -

INDLEDNING DER GENNEMSYRER ALLE LIGE NU OG BILLIE EILISH ER, KORT SAGT, LYDEN Billies Musik Afspejler Nutiden Perfekt

”BILLIE TALER IND I NOGET AF DEN ISOLATION, DEN SOCIALE ANGST OG GLOBALE ANGST, INDLEDNING DER GENNEMSYRER ALLE LIGE NU OG BILLIE EILISH ER, KORT SAGT, LYDEN Billies musik afspejler nutiden perfekt. Hun ser AF NUET. HENDES MUSIK LYDER sig ikke tilbage, men hun efterligner heller ikke FARVER MÅDEN, nye kunstnere – hendes lyd er helt unik. Hun PRÆCIS, SOM MAN VILLE FORVENTE indfanger den snigende følelse af angst, der VI SER VERDEN PÅ. AF DET ÅRTI, VI HAR TAGET HUL PÅ – gennemsyrer verden i dag, og kanaliserer den HENDES TEKSTER OG MED ALLE DE SVAGHEDER, FEJL OG ud gennem sin mørke, syrede, helt hypnotiske og BEKYMRINGER, DER FØLGER MED. underligt opløftende musik. Det er fuldstændig IDÉER ER SÅ UNIKKE vildt, at Billie ikke engang er fyldt 20 år endnu. Folk har brugt så mange forskellige ord til at OG SÅ KREATIVE OG beskrive Billie, siden hun dukkede op på den internationale musikscene i 2015 – på mystisk, magisk vis og uden varsel. Alle ordene er rigtige. Og forkerte. For ingen af dem betyder noget. SÅ GENIALE, MEN Billie er Billie. Billie har lært os, at det eneste, der virkelig betyder noget, er at være præcis den, man HUN ER OGSÅ STADIG selv vil være. Både fans og anmeldere roser Billie for hendes autenticitet, hendes tiltro til sin TEENAGER, OG HUN egen kreative vision og hendes store selvsikkerhed. Hun følger ikke reglerne – heller ikke sine egne. Selv de rigtig store rocknavne bakker op om Billie og beskriver hende som en moderne PRØVER IKKE PÅ AT rebel, der gør oprør mod alt og ingenting. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Seek Business Plan the Future of Live Entertainment

Berklee Valencia Culminating Experience: Seek Business Plan The Future Of Live Entertainment Developed by Alexandra Morancy 2 Table of Contents I. Table Of Contents ............................................................ 2 II. Participation Form ........................................................... 3 III. Introduction .................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................ 4 Company Description .......................................................... 5 Company Structure (Management) ..................................... 8 IV. Analysis .......................................................................... 9 Industry Analysis ................................................................. 9 Market Analysis ................................................................. 17 Internal Analysis (Economics) ........................................... 22 V. Plan Of Action ............................................................... 30 Operations Plan ................................................................ 30 Strategic and Marketing Plan ............................................ 36 Time Line (Gantt Diagram) ................................................ 42 Financial Projections ......................................................... 43 VI. Bibliography ................................................................. 52 VII. Appendices .................................................................. 56 3 4 III. -

INSAM-Journal-4-Full-Issue-15.7.2020

INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music, Art and Technology Issue No. 4 Sarajevo, July 2020 INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music, Art and Technology Journal of INSAM Institute for Conteporary Artistic Music ISSN 2637-1898 (online) COBISS.BH-ID 26698502 UDC 78: 792 editor-in-chief Bojana Radovanović (Serbia) editorial board Hanan Hadžajlić (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Ališer Sijarić (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Dino Rešidbegović (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Lana Paćuka (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Milan Milojković (Serbia) Aneta Stojnić (United States) Rifat Alihodžić (Montenegro) Ernest Ženko (Slovenia) Miloš Bralović (Serbia) Ana Đorđević (Ireland) editorial assistant Rijad Kaniža (Bosnia and Herzegovina) international advisory board Vesna Mikić (Serbia) Miodrag Šuvaković (Serbia), Senad Kazić (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Biljana Leković (Serbia), Amra Bosnić (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Andrija Filipović (Serbia), Valida Akšamija-Tvrtković (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Ljubiša Jovanović (Serbia), Jelena Novak (Portugal), Claire McGinn (UK), Daniel Becker (Italy), Olga Majcen Linn (Croatia), Sunčica Ostoić (Croatia), Haris Hasić (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Omer Blentić (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Michael Edward Edgerton (Republic of China), Bil Smith (United States) proofreading Anthony McLean on the cover Sougwen Chung, Exquisite Corpus design and layout Milan Šuput, Bojana Radovanović Maglov, M., Human Vs. Machine..., Insam Journal, 4, 2020. publisher INSAM Institute for Contemporary Artistic Music Podgaj 14, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina for the publisher Hanan