Arxiv:1612.03911V1 [Astro-Ph.HE] 12 Dec 2016 +2 −5 That They Probably Originate from Massive Stars Having and 8−1 × 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIXED STARS a SOLAR WRITER REPORT for Churchill Winston WRITTEN by DIANA K ROSENBERG Page 2

FIXED STARS A SOLAR WRITER REPORT for Churchill Winston WRITTEN BY DIANA K ROSENBERG Page 2 Prepared by Cafe Astrology cafeastrology.com Page 23 Churchill Winston Natal Chart Nov 30 1874 1:30 am GMT +0:00 Blenhein Castle 51°N48' 001°W22' 29°‚ 53' Tropical ƒ Placidus 02' 23° „ Ý 06° 46' Á ¿ 21° 15° Ý 06' „ 25' 23° 13' Œ À ¶29° Œ 28° … „ Ü É Ü 06° 36' 26' 25° 43' Œ 51'Ü áá Œ 29° ’ 29° “ àà … ‘ à ‹ – 55' á á 55' á †32' 16° 34' ¼ † 23° 51'Œ 23° ½ † 06' 25° “ ’ † Ê ’ ‹ 43' 35' 35' 06° ‡ Š 17° 43' Œ 09° º ˆ 01' 01' 07° ˆ ‰ ¾ 23° 22° 08° 02' ‡ ¸ Š 46' » Ï 06° 29°ˆ 53' ‰ Page 234 Astrological Summary Chart Point Positions: Churchill Winston Planet Sign Position House Comment The Moon Leo 29°Le36' 11th The Sun Sagittarius 7°Sg43' 3rd Mercury Scorpio 17°Sc35' 2nd Venus Sagittarius 22°Sg01' 3rd Mars Libra 16°Li32' 1st Jupiter Libra 23°Li34' 1st Saturn Aquarius 9°Aq35' 5th Uranus Leo 15°Le13' 11th Neptune Aries 28°Ar26' 8th Pluto Taurus 21°Ta25' 8th The North Node Aries 25°Ar51' 8th The South Node Libra 25°Li51' 2nd The Ascendant Virgo 29°Vi55' 1st The Midheaven Gemini 29°Ge53' 10th The Part of Fortune Capricorn 8°Cp01' 4th Chart Point Aspects Planet Aspect Planet Orb App/Sep The Moon Semisquare Mars 1°56' Applying The Moon Trine Neptune 1°10' Separating The Moon Trine The North Node 3°45' Separating The Moon Sextile The Midheaven 0°17' Applying The Sun Semisquare Jupiter 0°50' Applying The Sun Sextile Saturn 1°52' Applying The Sun Trine Uranus 7°30' Applying Mercury Square Uranus 2°21' Separating Mercury Opposition Pluto 3°49' Applying Venus Sextile -

A Transiting, Terrestrial Planet in a Triple M Dwarf System at 6.9 Parsecs

Draft version June 24, 2019 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX61 THREE RED SUNS IN THE SKY: A TRANSITING, TERRESTRIAL PLANET IN A TRIPLE M DWARF SYSTEM AT 6.9 PARSECS Jennifer G. Winters,1 Amber A. Medina,1 Jonathan M. Irwin,1 David Charbonneau,1 Nicola Astudillo-Defru,2 Elliott P. Horch,3 Jason D. Eastman,1 Eliot Halley Vrijmoet,4 Todd J. Henry,5 Hannah Diamond-Lowe,1 Elaine Winston,1 Xavier Bonfils,6 George R. Ricker,7 Roland Vanderspek,7 David W. Latham,1 Sara Seager,8, 9, 10 Joshua N. Winn,11 Jon M. Jenkins,12 Stephane´ Udry,13 Joseph D. Twicken,14, 12 Johanna K. Teske,15, 16 Peter Tenenbaum,14, 12 Francesco Pepe,13 Felipe Murgas,17, 18 Philip S. Muirhead,19 Jessica Mink,1 Christophe Lovis,13 Alan M. Levine,7 Sebastien´ Lepine´ ,4 Wei-Chun Jao,4 Christopher E. Henze,12 Gabor´ Furesz,´ 7 Thierry Forveille,6 Pedro Figueira,20, 21 Gilbert A. Esquerdo,1 Courtney D. Dressing,22 Rodrigo F. D´ıaz,23, 24 Xavier Delfosse,6 Chris J. Burke,7 Franc¸ois Bouchy,13 Perry Berlind,1 and Jose-Manuel Almenara6 1Center for Astrophysics j Harvard & Smithsonian, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2Departamento de Matem´atica y F´ısica Aplicadas, Universidad Cat´olica de la Sant´ısimaConcepci´on,Alonso de Rivera 2850, Concepci´on, Chile 3Department of Physics, Southern Connecticut State University, 501 Crescent Street, New Haven, CT 06515, USA 4Department of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30302-4106, USA 5RECONS Institute, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, 17201, USA 6Universit´eGrenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, F-38000 -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Gaia transients in galactic nuclei Citation for published version: Kostrzewa-Rutkowska, Z, Jonker, PG, Hodgkin, ST, Wyrzykowski, L, Fraser, M, Harrison, DL, Rixon, G, Yoldas, A, Leeuwen, FV, Delgado, A, Leeuwen, MV & Koposov, SE 2018, 'Gaia transients in galactic nuclei', Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society . https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty2221 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/mnras/sty2221 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 MNRAS 000, 1–19 (2018) Preprint 7 September 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Gaia transients in galactic nuclei Z. Kostrzewa-Rutkowska1,2⋆, P.G. Jonker1,2, S.T. Hodgkin3,L. Wyrzykowski4, M. Fraser5, D.L. Harrison3,6, G. Rixon3, A. Yoldas3, F. van Leeuwen3, A. Delgado3, M. van Leeuwen3, S. E. Koposov7,3 1SRON, Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Sorbonnelaan 2, 3584 CA Utrecht, the Netherlands 2Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University, P.O. -

A Unified Model of Tidal Destruction Events in the Disc-Dominated Phase

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–25 (2021) Printed 2021/04/14 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) A unified model of tidal destruction events in the disc-dominated phase Andrew Mummery? Oxford Astrophysics, Denys Wilkinson Building, Keble Road, Oxford, OX1 3RH, United Kingdom ABSTRACT We develop a unification scheme which explains the varied observed properties of TDEs in terms of simple disc physics. The unification scheme postulates that the different observed properties of TDEs are controlled by the peak Eddington ratio of the accretion discs which form following a stellar disruption. Our primary result is that the TDE population can be split into four subpopulations, which are (in order of decreasing peak Eddington ratio): “ob- scured” UV-bright and X-ray dim TDEs; X-ray bright soft-state TDEs; UV-bright and X-ray dim “cool” TDEs; and X-ray bright hard-state TDEs. These 4 subpopulations of TDEs will oc- cur around black holes of well defined masses, and our unification scheme is therefore directly testable with observations. As an initial test, we model the X-ray and UV light curves of six TDEs taken from three of the four subpopulations: ASASSN-14ae, ASASSN-15oi, ASASSN- 18pg, AT2019dsg, XMMSL1 J0740 & XMMSL2 J1446. We show that all six TDEs, spanning a wide range of observed properties, are well modelled by evolving relativistic thin discs. The peak Eddington ratio’s of the six best-fitting disc solutions lie exactly as predicted by the unified model. The mean stellar mass of the six sources is M? 0:24M . The so-called ‘missing energy problem’ is resolved by demonstrating thath onlyi ∼1% of the radiated accre- tion disc energy is observed at X-ray and UV frequencies. -

Name Affiliation Title Abstract Eliana Amazo

Name Affiliation Title Abstract Combined and simultaneous observations of high-precision photometric time-series acquired by TESS observatory and Comprehensive high-stability, high-accuracy measurements from Analysis of ESO/HARPS telescope allow us to perform a robust stellar Simultaneous magnetic-activity analysis. We retrieve information of the Photometric and Eliana Max Planck Institute photometric variability, rotation period and faculae/spot Spectropolarimetric Amazo- for Solar System coverage ratio from the gradient of the power spectra method Data in a Young Gomez Research (GPS). In addition magnetic field, chromospheric activity and Sun-like Star: radial velocity information are acquired from the Rotation Period, spectropolarimetric observations. We aim to identify the Variability, Activity possible correlations between these different observables and & Magnetism. place our results in the context of the magnetic activity characterization in low-mass stars. Asteroseismology is a powerful tool for probing stellar interiors and has been applied with great success to many classes of stars. It is most effective when there are many observed modes that can be identified and compared with theoretical models. Among evolved stars, the biggest advances have come for red giants and white dwarfs. Among main-sequence stars, great results have been obtained for low- mass (Sun-like) stars and for hot high-mass stars. However, at intermediate masses (about 1.5 to 2.5 ), results from the large number of so-called delta Scuti pulsating stars have been very disappointing. The delta Scuti stars are very numerous (about 2000 were detected in the Kepler field, mostly in long-cadence data). Many have a rich set of pulsation modes but, despite years of effort, the identification Asteroseismology of the modes has proved extremely difficult. -

CONSTELLATION INDUS - the INDIAN Indus Is a Constellation in the Southern Sky

CONSTELLATION INDUS - THE INDIAN Indus is a constellation in the southern sky. Created in the late sixteenth century, it represents an Indian, a word that could refer at the time to any native of Asia or the Americas. Indus was created between 1595 and 1597 and depicting an indigenous American Indian, nude, and with arrows in both hands, but no bow. Created at the time when Portuguese explorers of the 16th century were exploring North America, the constellation is generally believed to commemorate a typical American Indian that Columbus encountered when he reached the Americas. He was intending to reach India by sailing west and assumed it was ocean all the way around, and when he encountered land he thought for a short time that it was India and called the people he saw Indians. Despite the mistake, the name Indian stuck, and for centuries the native people of the Americas were collectively called Indians. Nowadays American Indians are known as Indigenous Americans. The word Indus comes from the name of India. It originally derived from the river Indus that originates in Tibet and flows through Pakistan into the Arabian Sea. The ancient Greeks called this river Indos. Related words are: Hindu, indigo (Greek indikon, Latin indicum, 'from India', a blue dye from India, derived from the plant Indigofera), indium (the element is named after indigo, which is the colour of the brightest line in its spectrum), This constellation is one of the 12 figures formed by the Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman from stars they charted in the southern hemisphere on their voyages to the East Indies at the end of the 16th century. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Unravelling the Nature of Hydrogen

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Unravelling the nature of hydrogen-poor thermonuclear supernovae Magee, Mark Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

The Proud Indian by Magda Streicher [email protected]

deep-sky delights The Proud Indian by Magda Streicher [email protected] What an honour to represent your Image source: Stellarium.org na�on against the stars in the heavens as one of the newer constella�ons, Indus, which, as many people know, is named a�er the American Indians. In China it has also been known as The Persian, a �tle from the Jesuit also be a triple star (see sketch). The missionaries (Star Names Their Lore stars form an upside down Y which and Meaning – Allen). can be seen very clearly with higher magnifica�on. This faint constella�on is located between the two magnificent starry Indus is also one of those constella- birds Grus and Pavo. The word �ons containing a large number of “colourful” is synonymous with the galaxies. NGC 7038, the first of many, American Indians as reflected in their can be found in the north-eastern cor- tradi�onal clothing. The constella�on ner. The galaxy is immediately seen as was named by Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser. Frederick de Houtman mapped the southern sky during an expedi�on to the East in about 1596. The author’s faithful Streicher asterisms are always a blessing to fall back on. STREICHER 65 is situated 2o north of the magnitude 3 orange- coloured alpha Indi, which could indicate the head of the Indian figure. The asterism displays an elongated handful of varied-magnitude stars with the brightest magnitude 8.2 (GSC 8406808) to the south-east, which may 176 mnassa vol 71 nos 7 & 8 177 august 2012 the proud indian a rela�vely bright oval in a north-west to south-east di- rec�on, displaying a star-like nucleus. -

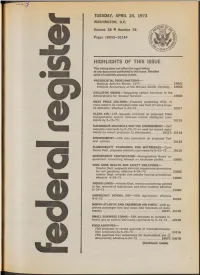

Highlights of This Issue

TUESDAY, APRIL 24, 1973 WASHINGTON, D.C. HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE This listing does not affect the legal status of any document published in this issue. Detailed table of contents appears inside. PRESIDENTIAL PROCLAMATIONS— National Arthritis Month, 1973............................................ 10067 Thirtieth Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising— 10065 EXECUTIVE ORDER— Delegating certain functions to the Administrator for General Services............ ......... ....... ... 10069 MEAT PRICE CEILINGS— Products containing 65% or more meat to be Controlled under new Cost of Living Coun cil definition; effective 3 -2 9 -7 3 ................................................. 10077 CLEAN AIR— EPA requests comment on proposed State transportation and/or land-use control strategies; com ments by 5 -1 5 -7 3 ........................................................................ 10119 HAZARDOUS MATERIALS AND THE ENVIRONMENT— DoT requests comments by 5 -2 2 -7 3 on need for impact state ments on recent proposals (2 documents)............. 10117, 10118 ENVIRONMENT— EPA lists comments on proposed Fed eral actions............. ........................................... ..... ..................... 10133 FLAMMABILITY STANDARDS FOR MATTRESSES— Com merce Dept, proposed revision; comments by 5 -2 1 -7 3 ...... 10110 GOVERNMENT CONTRACTING— Renegotiation Board re quirement concerning interest on excessive profits........... 10085 COAL MINE HEALTH AND SAFETY VIOLATIONS— Interior Dept, suspends informal assessment procedures for civil penalties; -

Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement

Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement 1. STUDENT DETAILS Gregory Charles Brown 1258033 2. THESIS DEPOSIT 2.1 I understand that under my registration at the University, I am required to deposit my thesis with the University in BOTH hard copy and in digital format. The digital version should normally be saved as a single pdf file. 2.2 The hard copy will be housed in the University Library. The digital ver- sion will be deposited in the Universitys Institutional Repository (WRAP). Unless otherwise indicated (see 2.3 below) this will be made openly ac- cessible on the Internet and will be supplied to the British Library to be made available online via its Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) service. [At present, theses submitted for a Masters degree by Research (MA, MSc, LLM, MS or MMedSci) are not being deposited in WRAP and not being made available via EthOS. This may change in future.] 2.3 In exceptional circumstances, the Chair of the Board of Graduate Studies may grant permission for an embargo to be placed on public access to the hard copy thesis for a limited period. It is also possible to apply separately for an embargo on the digital version. (Further information is available in the Guide to Examinations for Higher Degrees by Research.) 2.4 (a) Hard Copy I hereby deposit a hard copy of my thesis in the University Library to be made publicly available to readers immediately. I agree that my thesis may be photocopied. (b) Digital Copy I hereby deposit a digital copy of my thesis to be held in WRAP and made available via EThOS. -

KIPMUAR2016.Pdf

Kavli IPMU Kavli Annual Report 2016 Annual pril 2017 2016–March A April 2016–March 2017 Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU) The University of Tokyo Institutes for Advanced Study Kavli IPMU The University of Tokyo ANNUAL REPORT 2016 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8583, Japan TEL: +81-4-7136-4940 FAX: +81-4-7136-4941 http://www.ipmu.jp/ ISSN 2187-7386 Printed in Japan Copyright © 2017 Kavli IPMU All rights reserved Editors: Tomiyoshi Haruyama (Chair), Chiaki Hikage Editing Staff: Shoko Ichikawa Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe UTIAS, The University of Tokyo 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8583, Japan Tel: +81-4-7136-4940 Fax: +81-4-7136-4941 http://www.ipmu.jp/ CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 NEWS&EVENTS 8 3 ORGANIZATION 10 4 STAFF 14 5 RESEARCHHIGHLIGHTS 20 5.1 Newly Discovered Strong Lenses in HSC Data ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 20 5.2 Rare B Decay Anomaly and U(1)(B−L)3 ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 21 5.3 Wonderful Compactifications of Moduli Spaces ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 22 5.4 The Search for CP Violation in Neutrino Oscillations at T2K and Beyond ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 23 5.5 First Public Data Released by the Hyper Suprime-Cam Subaru Strategic Program ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 26 5.6 Discovery of the Two Faint Satellites in the Milky Way by the Hyper Suprime-Cam