The Conservation and Display of Ancient Roman Floor Mosaics in Situ and in Museums Erin M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greece and Rome

Spartan soldier HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Ancient Greece and Rome Reader Amphora Alexander the Great Julius Caesar Caesar Augustus THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. Ancient Greece and Rome Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Antioch Mosaics and Their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics

JMR 5, 2012 43-57 Antioch Mosaics and their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics José Maria BLÁZQUEZ* – Javier CABRERO** The twenty-two myths represented in Antioch mosaics repeat themselves in those in Hispania. Six of the most fa- mous are selected: Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta and Iphigenia in Aulis. Key words: Antioch myths, Hispania, Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta, Iphigenia in Aulis During the Roman Empire, Hispania maintained good cultural and economic relationships with Syria, a Roman province that enjoyed high prosperity. Some data should be enough. An inscription from Málaga, lost today and therefore from an uncertain date, seems to mention two businessmen, collegia, from Syria, both from Asia, who might form an single college, probably dedicated to sea commerce. Through Cornelius Silvanus, a curator, they dedicated a gravestone to patron Tiberius Iulianus (D’Ors 1953: 395). They possibly exported salted fish to Syria, because Málaca had very big salting factories (Strabo III.4.2), which have been discovered. In Córdoba, possibly during the time of Emperor Elagabalus, there was a Syrian colony that offered a gravestone to several Syrian gods: Allath, Elagabab, Phren, Cypris, Athena, Nazaria, Yaris, Tyche of Antioch, Zeus, Kasios, Aphrodite Sozausa, Adonis, Iupiter Dolichenus. They were possible traders who did business in the capital of Bética (García y Bellido 1967: 96-105). Libanius the rhetorical (Declamatio, 32.28) praises the rubbles from Cádiz, which he often bought, as being good and cheap. -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

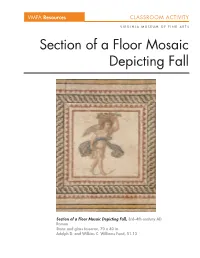

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

Early Peoples Activity Sheet: Ancient Romans

Early Peoples Activity Sheet: Ancient Romans 1. Physical features and background a) What is the name of the river than runs through the city of Rome? The Tiber River. b) When was the city of Rome founded? Legend says that the city was founded in 753 B.C. although evidence uncovered by archaeologists suggests that the city emerged around 600 B.C. c) Read the section on The Founding of Rome on page 5. Look at the bronze sculpture beneath it. Explain what the sculpture is depicting? The sculpture depicts the she-wolf who cared for the abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, until they were rescued by a shepherd who brought them up as his own children. d) Looking at the dates the sculpture is thought to be made. Is this a primary or secondary source? Secondary. e) According to the legend of the founding of Rome, where does Rome get its name from? The founder of the city, Romulus. f) Look at the Timeline of Rome, also on page 5. When was the Roman Empire at its greatest size? Under the Emperor Trajan between A.D. 98-117. g) Name the several groups of people living on the Italian peninsula during the first millennium B.C.? To the East were the Sabines, to the South were the Samnites. The ancient Greeks had colonies along the coast of Southern Italy and in Sicily. People from Carthage had settled in northwest Sicily. To the north of the Italian peninsula were the Etruscans. h) Describe the landscape that early Rome was built on? Rome was founded on seven hills. -

Unique Representation of a Mosaics Craftsman in a Roman Pavement from the Ancient Province Syria

JMR 5, 2012 103-113 Unique Representation of a Mosaics Craftsman in a Roman Pavement from the Ancient Province Syria Luz NEIRA* The subject of this paper is the study of the figured representation of a mosaics-craftsman in a fragmentary pavement, preserved in the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Of unknown provenance, apparently comes from the territory of ancient Syria in the Eastern Roman Empire. Such representation is a hapax, not only in the Roman mosaics of Syria, but also in the corpus of Roman Empire, since, although several mosaic inscriptions in some pavements, which show the name of the mosaic artisans and / or different names for different functions of the trades related to the development of mosaics, and even the reference to the workshop, who were teachers or members of his team of craftsmen, the figured representation of a mosaicist, in the instant to be doing his work, is truly unique. Keywords: mosaic, mosaics-craftsman, Syria, Eastern Roman Empire, Late Antiquity. When in 1998 I had the opportunity to visit the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, I could see between the collections of exposed mosaics a fragment with the figure of a man represented at the instant of having, hammer in hand, the tesserae of a mosaic. Years later, when tackling a study on the jobs of artists and artisans in the roman mosaics1, checked its absence in the bibliography, nevertheless extensive and prolix on the subject, and put me in contact with the director of the Classical Antiquities Department in the Danish Museum, Dr. John Lund, who, to my questions2 about the origin of the fragment, kindly answered me. -

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

A Satyr for Midas: the Barberini Faun and Hellenistic Royal Patronage Author(S): Jean Sorabella Reviewed Work(S): Source: Classical Antiquity, Vol

A Satyr for Midas: The Barberini Faun and Hellenistic Royal Patronage Author(s): Jean Sorabella Reviewed work(s): Source: Classical Antiquity, Vol. 26, No. 2 (October 2007), pp. 219-248 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ca.2007.26.2.219 . Accessed: 08/02/2012 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Classical Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org JEAN SORABELLA A Satyr for Midas: The Barberini Faun and Hellenistic Royal Patronage The canonical statue known as the Barberini Faun is roundly viewed as a mysterious anomaly. The challenge to interpret it is intensiWed not only by uncertainties about its date and origin but also by the persistent idea that it represents a generic satyr. This paper tackles this assumption and identiWes the statue with the satyr that King Midas captured in the well-known myth. Iconographic analysis of the statue’s pose supports this view. In particular, the arm bent above the head, the twist of the torso, and the splay of the legs are paralleled in many well-understood Wgures and furnish keys to interpreting the Barberini Faun as an extraordinary sleeping beast, intoxicated and Wt for capture. -

11 Amazing Day Trips You Can Take from Naples

22 JANUARY 2018 NEEN 3535 11 AMAZING DAY TRIPS YOU CAN TAKE FROM NAPLES One of the greatest benefits of visiting Naples is its close access to many nearby beaches, cathedrals, museums, and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Italy’s central coastline offers stunning natural scenery which continues to draw millions of tourists from around the world who come to eat, drink, and be merry under the silhouette of Naples historic past. Whether you’ve come to Naples to taste the region’s famous pizza, explore the elongated coastline, enjoy a cultural performance, or learn more about Italy’s rich heritage—there’s never a dull moment in your adventure with Ciao Florence. Embrace the spirit of “dolce vita” or the “sweet life” as our expert guides take you on a perfectly curated journey around the region of Campania. Florence based Tour Operator offers 11 different day trips from Naples to choose from, allowing you to tailor your Italian experience to satisfy your wanderlust. Indulge in the beautiful tranquility of the Italian countryside as we travel by bus, train, and even boat to cities like Pompeii, Capri, Sorrento, and the Amalfi Coast. Along the way you will be given lots of time to explore these cities for a more intimate connection to this historic Italian landscape. Whichever route you choose, feel confident that you are getting the most out of your Italian experience when you travel with Ciao Florence. From Naples to Pompeii Visit the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Pompeii which was made infamous in the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. -

Myth Unit 10 Page Draft

Origin and Foundation Myths of Rome as presented in Vergil, Ovid and Livy Mary Ann T. Natunewicz INTRODUCTION This unit is part of a two-semester course in a third or fourth-year Latin curriculum. Ideally, Vergil should be the author read at the fourth year level. However, because the Cicero and Vergil are offered alternate years, some students will be less advanced. Students enter the course after a second year program that included selections from Caesar’s Gallic War and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Students who enter after three years of Latin will have read several complete Ciceronian orations and selections from Latin poets such as Catullus, Ovid, and some Horace. The fourth year includes the reading of the Aeneid, Books I and IV in toto, and selections from Books II, VI and VIII. The remaining books are read in English translation. The school is on the accelerated block system. Each class meets every day for ninety minutes. This particular unit will be used in several sections of the course, but most of it will be used in the second semester. I plan to rewrite into simplified Latin prose selections from each author. These adaptations could then be read by first or second year students. This unit has been written specifically for Latin language courses. However, by reading the suggested translations, the information and the unit could be adapted for literature or history courses that include material that deals with the ancient Mediterranean world. DISCUSSION OF THE UNIT The culmination of a high school Latin course is the reading of large sections of Vergil’s epic poem, the Aeneid, which is the story of Aeneas’ struggles to escape Troy and to found the early settlement which is the precursor to Rome.