Annual State of Cross-Border Operations Report (March 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declaration Amendment of National Road N11 Section 11

STAATSKOERANT, 13 OKTOBER 2010 No.33628 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT No. 902 13 October 2010 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL RQADS AGENCY LIMITED Registration No: 98/09584/06 DECLARATION AMENDMENT OF NATIONAL ROAD N11 SECTION 11 AMENDMENT OF DECLARATION NO. 1137 OF 2005. By virtue of section 40(1 )(b) of the South African National Roads Agency Limited and the National Roads Act, 1998 (Act No.7 of 1998), I hereby amend Declaration No. 1137 of 2005 Annexure paragraph (II) by substituting it, with the subjoined sheets 1 to 7 of Plan No. P769/09. (National Road N11 Section 11: Groblersdal - Marble Hall) MINiSTER OF T ANSPORT Y -J 9 500 REM PTN.37 REM PTN.55 I LEASE GROBLERS AREA y CDJ o 9 00 R.O.W.SERV. - 0 ~ ~ REM PTN.13 REM "< PTN.69 REM ..... --& PTN.79 PTN.30 o --- ..... <n Z -..\. ... ' PTN.78 REM L<V~ " R15 PTN.2 _.) 9' .l: REM ,*,' ,," / ~ ~ (y" REM PTN.80 "< REM PTN.55 "< .,," PTN.68 REM KLiPBANK 26 -JS y -39 000 PTN.69 ( KROKODILDRIFT 25-JS (J) .-.'" REM REM E. P .l. \ REM PTN.63 PTN.11 PTN.5 N REM REM PTN. 14 + SERVo \ ~ REM PTN.30 x \ PTN.45 '--I PTN.78 PTN.75 (J) \ ;<; LIS rl, lI6 L 17/ \ LIB ':'" o R16A ..... "···~~A·:·-:-:-:·>i;·;-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:~;:; m "-< lJ R1B R19 \ o 0 :t> REM o \ 0 lfl 0 Z PTN.30 _--I o 0 REM PTN.18 REM REM REM PTN.1 .-.'" '".-. <.V Y/-J9500 PTN.52 N + o X q o KROKODILDRIFT 25-JS OJ Y -391000 REM REM m O~ooo R.O.W.\ REM PTN.35 PTN.8 lJ SERV.\ PTN.37 N REM PTN.5 PTN.24 o 1\ PTN.52 ... -

REUNERT LIMITED (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa

REUNERT LIMITED (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) (Registration number: 1913/004355/06) ISIN: ZAE000057428 Share code: RLO (“Reunert” or the “Company” or the “Group”) FINALISATION OF ACQUISITION OF SHARES IN ACCORDANCE WITH CSP HEDGING TRANSACTION Reunert shareholders (“Shareholders”) are referred to the announcement published on SENS on 30 September 2020 wherein Shareholders were advised of the hedging transaction entered into between Reunert and Investec Bank Limited (“Investec”), an independent third party, on behalf of the Reunert 2019 Conditional Share Plan (“CSP”), to hedge the potential future obligations of the CSP (the “Hedging Transaction”), as provided for in the CSP rules. As required by the JSE Limited Listings Requirements (“Listings Requirements”), a purchase programme was put in place prior to the commencement of Reunert’s closed period on 1 October 2020. In accordance with paragraph 14.9(f) of schedule 14 of the Listings Requirements, Shareholders are advised of the following acquisitions of Reunert ordinary shares (“Shares”) on behalf of the CSP, in execution of the Hedging Transaction, between 30 September 2020 and 19 November 2020: Name of entity: Investec, on behalf of the CSP Class of securities: Ordinary shares Nature of transaction: Purchase of Shares pursuant to the Hedging Transaction Transaction completed: On-market Total number of Shares acquired: 2 346 930 Total value of Shares acquired: R79 032 108 Nature of interest: Indirect beneficial (purchased by Investec acting as an independent agent on -

Emalahleni Local Municipality Integrated Development Plan | 2019/2020 Final Idp

TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSPECTIVE FROM THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR .................................................................. I PERSPECTIVE OF THE SPEAKER ........................................................................................ III PERSPECTIVE FROM THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER ........................................................... IV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................... V 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 LOCATION ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 GUIDING PARAMETERS ........................................................................................................ 5 1.1.1 LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 5 2 PROCESS PLAN ..................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION MEETINGS ........................................................................................... 23 3 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................ 26 3.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... -

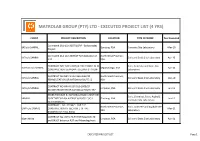

Matrolab Group (Pty) Ltd - Executed Project List (4 Yrs)

MATROLAB GROUP (PTY) LTD - EXECUTED PROJECT LIST (4 YRS) CLIENT PROJECT DESCRIPTION LOCATION TYPE OF WORK Year Executed Contract N.001-192-2007/1GFIP - Ballustrades BKS c/o SANRAL Gauteng, RSA Concrete Site Laboratory Mar-10 Project Contract N.012-112-2009/1F Rehabilitation of North West Province, KV3 c/o SANRAL Soils and Seals Site Laboratory Apr-10 N12 RSA CONTRACT N017-030-2005/4 FOR DNNN2: NEW Soils, Concrete and Seals Site Aurecon c/o SANRAL Mpumalanga, RSA Apr-10 CONSTRUCTION: LEANDRA TO LEVEN STATION Laboratory CONTRACT NO NRA N.012-140-2009/1F North West Province, KV3 c/o SANRAL Soils and Seals Site Laboratory Dec-10 REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL ROUTE 12 RSA CONTRACT NO NRA R.037-010-2008/2F KV3 c/o SANRAL Limpopo, RSA Soils and Seals Site Laboratory Jan-11 RECONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL ROUTE R37 WORK PACKAGE B: NATIONAL ROAD 1 SECTION Soils, Chemical, Seals, Asphalt, SANRAL 20 BETWEEN 14th AVENUE & BUCCLEUCH Gauteng, RSA Jan-11 Concrete Site Laboratory INTERCHANGES CONTRACT : NO. 27199/1 FOR THE North West Province, Soils, Concrete and Asphalt Site UWP c/o SANRAL CONSTRUCTION OF SECTION 1 OF THE Mar-11 RSA Laboratory BAKWENA N4 TOLL ROAD CONTRACT No. 0245-70-49 FOR Road D4170 Bigen Africa Limpopo. RSA Soils and Seals Site Laboratory Apr-11 and D4167 between R37 and Maandagshoek EXECUTED PROJECT LIST Page 1 MATROLAB GROUP (PTY) LTD - EXECUTED PROJECT LIST (4 YRS) Jeffares & Green c/o CONTRACT N007-023-2010/1F: Moorreesburg Western Cape Soils and Seals Site Laboratory May-11 SANRAL HHO Africa c/o City of CONTRACT C880: Koeberg Interchange -

Client: Pixley Ka Isaka Seme Local Municipality Private Bag X9011 Volksrust 2470

Client: Pixley Ka Isaka Seme Local Municipality Private Bag X9011 Volksrust 2470 Assisted By: Urban Dynamics (Mpumalanga) Inc. PO Box 3294 Middelburg 1050 Funded by: Gert Sibande District Municipality PO Box 550 Secunda 2302 Date: 30 November 2010 i Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................................1 1.0 THE NEED FOR A SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK...........................................................................................1 1.1 TERMS OF REFERENCE...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT......................................................................................................................................................4 2.1 LEGISLATIVE REQUIREMENTS...................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 IDP & DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY LINKAGE.............................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.3 CURRENT PLANNING ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

SANRAL Toll Tariff Booklet.Pdf

PLEASE NOTE ADJUSTED TOLL TARIFFS EFFECTIVE FROM 12 APRIL 2018 Toll tariffs and discounts applicable to the conventional toll plazas, effective 12 April 2018 Do note that this booklet is an explanatory document and does not replace the Government Gazette No. 41545 on adjusted toll tariffs as published on 29 March 2018. Adjustments to the toll tariffs include the increase in Value Added Tax (VAT) from 14% to 15% as announced by the Minister of Finance in the 2018/19 Budget Speech. PLAZA CLASS 1 CLASS 2 CLASS 3 CLASS 4 N1 HUGUENOT Mainline R38,00 R105,00 R164,00 R266,00 VERKEERDEVLEI Mainline R54,50 R109,00 R164,00 R230,00 VAAL Mainline R63,50 R120,00 R144,00 R192,00 GRASMERE Mainline R19,00 R57,00 R67,00 R88,00 Ramp (S) R10,00 R29,00 R34,00 R44,00 Ramp (N) R10,00 R28,00 R33,00 R44,00 STORMVOËL Ramp R9,00 R22,00 R26,00 R31,00 ZAMBESI Ramp R10,50 R26,00 R31,00 R37,00 PUMULANI Mainline R11,50 R29,00 R33,00 R40,00 WALLMANSTHAL Ramp R5,20 R13,00 R16,00 R18,50 MURRAYHILL Ramp R10,50 R26,00 R32,00 R37,00 HAMMANSKRAAL Ramp R24,50 R85,00 R92,00 R106,00 CAROUSEL Mainline R53,00 R142,00 R157,00 R182,00 MAUBANE Ramp R23,00 R62,00 R68,00 R79,00 KRANSKOP Mainline R43,00 R109,00 R146,00 R179,00 Ramp R12,00 R32,00 R38,00 R56,00 NYL Mainline R55,50 R104,00 R125,00 R168,00 Ramp R17,00 R32,00 R38,00 R48,00 SEBETIELA Ramp R17,00 R32,00 R40,00 R54,00 CAPRICORN Mainline R44,50 R122,00 R142,00 R178,00 BAOBAB Mainline R43,00 R117,00 R161,00 R194,00 R30 BRANDFORT Mainline R43,50 R87,00 R131,00 R184,00 N2 TSITSIKAMMA Mainline/ Ramp R50,50 R127,00 R305,00 R431,00 -

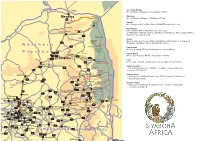

N O R T H E R N P R O V I N

Beitbridge Crocodile Bridge N4 via Witbank & Nelspruit to Komatipoort 475 km Pafuri Gate 25 Malelane Messina R5 N4 via Witbank & Nelspruit to Malelane 428 km N1 Tshipise R525 Punda Numbi Maria N4 to Nelspruit, R40 to White River, R538/R539 to Numbi 411 km Oorwinning 4 52 Paul Kruger Thohoyandou R Louis Trichardt N4 to Nelpruit, R40 to Hazyview, turn right to gate, R524 or 460 km N4 to Belfast, R540 to Lydenburg via Dullstroom, R37 to Sabie, R536 to Tshakhuma Hazyview, on to gate 470 km R81 Klein Shingwedzi Letaba Orpen Bateleur Bushveld N4 to Belfast, R540 to Lydenburg via Dullstroom, R36 and R531 to Orpen via R36 Camp Ohrigstad, JG strijdom Tunnel and Klaserie. 490 km R K r u g e r 5 2 NorthernR R81 Nkomo Mopani 9 5 2 Phalaborwa 1 Shimuwini Rita Bushveld N1 to Pietersburg, R71 to Phalaborwa via Tzaneen 490 km Camp R81 Province N1 La Cotte Tzaneen Punda Maria R71 R71 Murchison N1 to Louis Trichardt, R524 to Punda Maria 550 km Letsitele 9 R71 1 R37PIETERSBURG Gravelotte 5 R Namakgale Pafuri R40 30 Phalaborwa N1 to Louis Trichardt, on to Messina, but turn right at R525 600 km R5 N a t i o n a l Potgietersrus D Mica R35 R R36 Klaserie Southern Gates R518 R37 A Hoedspruit N.R. – N4 Toll Road (Gauteng – Witbank – Nelspruit –Hazyview/Malelane) K N1 Timbavati +- 4 hours [3 toll gates] E 27 R5 Game R Reserve 5 N R Kampersrus 7 5 9 S 3 O R P E N Central Gates Nylstroom 1 Acornhoek G AT E Nwanetsi Branddraai 32 B Blyde R531 R R5 Manyeleti – Gauteng – N1 Toll Road Pietersburg – R 71 Tzameem – Phalaborwa 5 River 5 Canyon 5 E G.R. -

2018 INTEGRATED REPORT Volume 1

2018 INTEGRATED REPORT VOLUME 1 Goals can only be achieved if efforts and courage are driven by purpose and direction Integrated Report 2017/18 The South African National Roads Agency SOC Limited Reg no: 1998/009584/30 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY SOC LIMITED The South African National Roads Agency SOC Limited Integrated Report 2017/18 About the Integrated Report The 2018 Integrated Report of the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) covers the period 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 and describes how the agency gave effect to its statutory mandate during this period. The report is available in printed and electronic formats and is presented in two volumes: • Volume 1: Integrated Report is a narrative on major development during the year combined with key statistics that indicate value generated in various ways. • Volume 2: Annual Financial Statements contains the sections on corporate governance and delivery against key performance indicators, in addition to the financial statements. 2018 is the second year in which SANRAL has adopted the practice of integrated reporting, having previously been guided solely by the approach adopted in terms of the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA). The agency has attempted to demonstrate the varied dimensions of its work and indicate how they are strategically coherent. It has continued to comply with the reporting requirements of the PFMA while incorporating major principles of integrated reporting. This new approach is supported by the adoption of an integrated planning framework in SANRAL’s new strategy, Horizon 2030. In selecting qualitative and quantitative information for the report, the agency has been guided by Horizon 2030 and the principles of disclosure and materiality. -

2 South Africa's Agricultural Sector

David Neves and Cyriaque Hakizimana Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 47 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: South Africa Country Report David Neves and Cyriaque Hakizimana Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 47 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editing and Proofreading: Liz Sparg Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: David Neves Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme/ ESRC grant ES/J009261/1 Contents List of tables ............................................................................................................................................................... ii List of figures ............................................................................................................................................................iii Acronyms and abbreviations.............................................................................................................................. iv 1 Introduction -

Toll Tariffs 2021

TOLL TARIFFS 2021 EFFECTIVE FROM 1 MARCH 2021 TOLL TARIFFS AND DISCOUNTS APPLICABLE TO THE CONVENTIONAL TOLL PLAZA, EFFECTIVE 01 MARCH 2021 Do note that this booklet is an explanatory document and does not replace the Government Gazette No. 44145, No. 44146, No. 44147, No. 44148 and No. 44149 on adjusted toll tariffs as published on 11 February 2021. PLAZA CLASS 1 CLASS 2 CLASS 3 CLASS 4 N1 HUGUENOT Mainline R42.50 R118.00 R185.00 R300.00 VAAL Mainline R71.50 R135.00 R162.00 R216.00 GRASMERE Mainline R21.50 R64.00 R75.00 R99.00 Ramp (N) R11.00 R32.00 R38.00 R49.00 Ramp (S) R11.00 R32.00 R38.00 R49.00 VERKEERDEVLEI Mainline R61.50 R123.00 R185.00 R260.00 STORMVOËL Ramp R10.00 R25.00 R29.00 R35.00 ZAMBESI Ramp R12.00 R30.00 R35.00 R42.00 PUMULANI Mainline R13.00 R32.00 R37.00 R45.00 WALLMANSTHAL Ramp R6.00 R15.00 R18.00 R20.50 MURRAYHILL Ramp R12.00 R30.00 R36.00 R41.00 HAMMANSKRAAL Ramp R28.00 R95.00 R103.00 R119.00 CAROUSEL Mainline R60.00 R160.00 R177.00 R204.00 MAUBANE Ramp R26.00 R69.00 R77.00 R89.00 KRANSKOP Mainline R48.50 R123.00 R165.00 R202.00 Ramp R13.50 R36.00 R42.00 R63.00 NYL Mainline R62.50 R117.00 R141.00 R189.00 Ramp R19.50 R36.00 R42.00 R54.00 SEBETIELA Ramp R19.50 R36.00 R45.00 R60.00 BAOBAB Mainline R48.50 R132.00 R181.00 R218.00 CAPRICORN Mainline R50.00 R137.00 R161.00 R201.00 R30 BRANDFORT Mainline R49.00 R98.00 R148.00 R208.00 N2 TSITSIKAMMA Mainline /Ramp R57.00 R144.00 R343.00 R486.00 IZOTSHA Ramp R10.00 R18.00 R24.00 R42.00 ORIBI Mainline R32.00 R57.00 R78.00 R127.00 Ramp (S) R14.50 R27.00 R36.00 R57.00 Ramp (N) -

2019 Toll Tariffs and Discounts Applicable to the Conventional Toll Plaza, Effective 1 March 2019

TOLL TARIFFS 2019 EFFECTIVE FROM 1 MARCH 2019 TOLL TARIFFS AND DISCOUNTS APPLICABLE TO THE CONVENTIONAL TOLL PLAZA, EFFECTIVE 1 MARCH 2019 Do note that this booklet is an explanatory document and does not replace the Government Gazette No. 42209 on adjusted toll tariffs as published on 1 February 2019. PLAZA CLASS 1 CLASS 2 CLASS 3 CLASS 4 N1 HUGUENOT Mainline R39,50 R110,00 R172,00 R278,00 VERKEERDEVLEI Mainline R57,00 R114,00 R172,00 R241,00 VAAL Mainline R66,50 R125,00 R150,00 R200,00 GRASMERE Mainline R20,00 R60,00 R70,00 R92,00 Ramp (N) R10,00 R30,00 R35,00 R46,00 Ramp (S) R10,00 R30,00 R35,00 R46,00 STORMVOËL Ramp R9,50 R23,00 R27,00 R32,00 ZAMBESI Ramp R11,00 R28,00 R32,00 R39,00 PUMULANI Mainline R12,00 R30,00 R35,00 R42,00 WALLMANSTHAL Ramp R5,60 R14,00 R16,50 R19,50 MURRAYHILL Ramp R11,00 R28,00 R33,00 R39,00 HAMMANSKRAAL Ramp R26,00 R89,00 R96,00 R111,00 CAROUSEL Mainline R56,00 R150,00 R165,00 R191,00 MAUBANE Ramp R24,00 R65,00 R72,00 R83,00 KRANSKOP Mainline R45,00 R114,00 R153,00 R187,00 Ramp R12,50 R33,00 R39,00 R59,00 NYL Mainline R58,00 R108,00 R131,00 R175,00 Ramp R18,00 R33,00 R39,00 R50,00 SEBETIELA Ramp R18,00 R33,00 R42,00 R56,00 CAPRICORN Mainline R46,50 R127,00 R149,00 R187,00 BAOBAB Mainline R45,00 R122,00 R168,00 R202,00 R30 BRANDFORT Mainline R45,50 R91,00 R137,00 R193,00 N2 TSITSIKAMMA Mainline / Ramp R53,00 R133,00 R319,00 R450,00 IZOTSHA Ramp R9,50 R17,00 R23,00 R39,00 ORIBI Mainline R29,50 R53,00 R73,00 R118,00 Ramp (S) R13,50 R25,00 R34,00 R53,00 Ramp (N) R16,00 R28,00 R39,00 R73,00 UMTENTWENI Ramp R12,50 -

South African Numbered Route Description and Destination Analysis

NATIONAL DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT RDDA SOUTH AFRICAN NUMBERED ROUTE DESCRIPTION AND DESTINATION ANALYSIS MAY 2012 Prepared by: TITLE SOUTH AFRICAN NUMBERED ROUTE DESCRIPTION AND DESTINATION ANALYSIS ISBN STATUS DOT FILE DATE 2012 UPDATE May 2012 COMMISSIONED BY: National Department of Transport COTO Private Bag x193 Roads Coordinating Body PRETORIA SA Route Numbering and Road Traffic 0001 Signs Committee SOUTH AFRICA CARRIED OUT BY: TTT Africa Author: Mr John Falkner P O Box 1109 Project Director: Dr John Sampson SUNNINGHILL Specialist Support: Mr David Bain 2157 STEERING COMMITTEE: Mr Prasanth Mohan Mr Vishay Hariram Ms Leslie Johnson Mr Schalk Carstens Mr Nkululeko Vezi Mr Garth Elliot Mr Msondezi Futshane Mr Willem Badenhorst Mr Rodney Offord Mr Jaco Cronje Mr Wlodek Gorny Mr Richard Rikhotso Mr Andre Rautenbach Mr Frank Lambert [i] CONTENTS DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... xi 2. TERMINOLOGY .......................................................................................................................... xi 3. HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT .......................................................................................... xii ROUTE DESCRIPTION – NATIONAL ROUTES NATIONAL ROUTE N1 .............................................................................................................................. 1 NATIONAL ROUTE N2 .............................................................................................................................