Keywords Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Fisheries Regulations 2018

FISHINGIN ACCORDANCE WITH THE LAW Public Fisheries Regulations 2018 ATTENTION! Consult the website of the ‘Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos’ (Nature and Forest Agency) for the full legislation and recent information. www.natuurenbos.be/visserij When and how can you fish? Night fishing To protect fish stocks there are two types of measures: Night fishing: fishing from two hours after sunset until two hours before sunrise. A large • Periods in which you may not fish for certain fish species. fishing permit of € 45.86 is mandatory! • Ecologically valuable waters where fishing is prohibited in certain periods. Night fishing is prohibited in the ecologically valuable waters listed on p. 4-5! Night fishing is in principle permitted in the other waters not listed on p. 4-5. April Please note: The owner or water manager can restrict access to a stretch of water by imposing local access rules so that night fishing is not possible. In some waters you might January February March 1 > 15 16 > 30 May June July August September October November December also need an explicit permit from the owner to fish there. Fishing for trout x x √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x Fishing for pike and Special conditions for night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ pikeperch Always put each fish you have caught immediately and carefully back into the water of origin. The use of keepnets or other storage gear is prohibited. Fishing for other √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ species You may not keep any fish in your possession, not even if you caught that fish outside the night fishing period. Night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Bobber fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Wading fishing x x √ √ x x √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x x Permitted x Prohibited √ Prohibited in the waters listed on p. -

The Kasterlee Formation and Its Relation with the Diest and Mol Formations in the Belgian Campine

GEOLOGICA BELGICA (2020) 23/3-4: xxx-xxx The Kasterlee Formation and its relation with the Diest and Mol Formations in the Belgian Campine NOËL VANDENBERGHE1,*, LAURENT WOUTERS2, MARCO SCHILTZ3, KOEN BEERTEN4, ISAAC BERWOUTS5, KOEN VOS5, RIK HOUTHUYS6, JEF DECKERS7, STEPHEN LOUWYE8, PIET LAGA9, JASPER VERHAEGEN10, RIEKO ADRIAENS11, MICHIEL DUSAR9. 1 Dept. Earth and Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium; [email protected]. 2 ONDRAF/NIRAS, Brussels, Belgium; [email protected]. 3 Samsuffit, Boechout, Belgium; [email protected]. 4 SCK, Mol, Belgium; [email protected]. 5 Sibelco, Belgium; [email protected]; [email protected]. 6 Consultant, Belgium; [email protected]. 7 VITO, Mol, Belgium; [email protected]. 8 Geology, UGent, Belgium; [email protected]. 9 Geological Survey of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium; [email protected]; [email protected]. 10 VPO, Planning Bureau for the Environment and Spatial Development, Department of Environment, Flemish Government, Koning Albert II-laan 20, 1000 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected]. 11 Qmineral, Heverlee-Leuven, Belgium; [email protected]. * corresponding author. ABSTRACT. Stratigraphic analysis of cored and geophysically logged boreholes in the Kasterlee-Geel-Retie-Mol-Dessel area of the Belgian Campine has established the presence of two lithostratigraphic units between the classical Diest and Mol Formations, geometrically related to the type Kasterlee Sand occurring west of the Kasterlee village and the study area. A lower ‘clayey Kasterlee’ unit, equivalent to the lithology occurring at the top of the Beerzel and Heist-op-den-Berg hills, systematically occurs to the east of the Kasterlee village. An overlying unit has a pale colour making it lithostratigraphically comparable to Mol Sand although its fine grain size, traces of glauconite and geometrical position have traditionally led stratigraphers to consider it as a lateral variety of the type Kasterlee Sand; it has been named the ‘lower Mol’ or ‘Kasterlee-sensu-Gulinck’ unit in this study. -

PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN BESTUURLIJK ARRONDISSEMENT ANTWERPEN Pagina 1 Van 48 PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN Datum: 17/08/2017

PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN Datum: 17/08/2017 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) D tot. C O diagn bijk erk opm V - V V + (V 1bis) C B C M C H CB AW CB AW B CB AW M BEG CAP BESTUURLIJK ARRONDISSEMENT ANTWERPEN VZW Emmaüs DE GROTE ROBIJN Korte Sint-Annastraat 4 2000 Antwerpen 16 23 Telefoon: 03 231 25 75 12-18j 0-18j j-m j-m Fax: E-mail: [email protected] VER Zorgbedrijf Antwerpen CENTRA BIJZONDERE JEUGDZORG ZORGBEDRIJF ANTWERPEN Ballaarstraat 35 53 2018 Antwerpen 25 43 4 3 3 Telefoon: 03 334 44 50 0-18j 0-18j 0-18j j-m j-m j-m Fax: E-mail: [email protected] AFDELINGEN: PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN BESTUURLIJK ARRONDISSEMENT ANTWERPEN Pagina 1 van 48 PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN Datum: 17/08/2017 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) D tot. C O diagn bijk erk opm V - V V + (V 1bis) C B C M C H CB AW CB AW B CB AW M BEG CAP 18 3 DE WENDING 13 0-18j j-m Lamorinièrestraat 236 12-18j j-m 2018 Antwerpen 29 3 PENNSYLVANIA FOUNDATION 13 0-18j j-m Gouverneur Holvoetlaan 28 0-18j j-m 2100 Antwerpen VZW Elegast ELEGAST Belgiëlei 203 20 158 2018 Antwerpen 12 15 6-18j 94 32 6 26 j-m Telefoon: 03 286 75 25 0-12j 0-18j 0-18j 0-18j j-m j-m j-m j-m Fax: E-mail: [email protected] AFDELINGEN: PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN BESTUURLIJK ARRONDISSEMENT ANTWERPEN Pagina 2 van 48 PROVINCIE ANTWERPEN Datum: 17/08/2017 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) D tot. -

Diptera: Ceratopogonidae; Odonata), with Notes on Its Ecology and Habitat

Forcipomyia paludis as a parasite of Odonata in Belgium 27. Februar 2021101 Forcipomyia paludis as a parasite of Odonata in Belgium (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae; Odonata), with notes on its ecology and habitat Geert De Knijf Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Havenlaan 88 bus 73, 1000 Brussels, Belgium, [email protected] Abstract The biting midge Forcipomyia paludis is the only ceratopogonid species known to para- sitise Odonata in Europe. This parasite is widely distributed in the Western Palaearctic, but has only once been formally cited for one damselfly species in Belgium. However, many photographs of parasitised Odonata are stored in the citizen science website www. waarnemingen.be in Belgium. A thorough analysis of 2,300 photographs from four sites from 2019 and 2020 resulted in the finding of 100 photographs of 32 species of odonate being parasitised in Belgium. We also found two species, Coenagrion scitulum and Sym petrum vulgatum for the first time mentioned as hosts. Virtually all F. paludis (99%) were found at the sites Buitengoor and Hageven. Biting midges were found in at least 13% of the photographs from Buitengoor and 3% in Hageven. Most records date from the end of May to the end of July. The parasite prevalence was low: 87% of the individuals carried only one or two midges. They seemed to have a slight preference for the forewings over the hind wings (59% versus 41%), but no difference was found between the right and the left wings. The presence of biting midges on Odonata was correlated with the pres- ence of Cladium mariscus vegetation. -

Uitbreiding Van Een Varkenshouderij Te Wuustwezel Tot 8.650 Vleesvarkens En Een Mestverwerkingsinstallatie Met Een Capaciteit Van 18.000 Ton/J

Uitbreiding van een varkenshouderij te Wuustwezel tot 8.650 vleesvarkens en een mestverwerkingsinstallatie met een capaciteit van 18.000 ton/j Kennisgeving/ontwerpMER: Tekstgedeelte M16LOBE1_kennisgeving/ontwerpMER Uitbreiding van een varkenshouderij te Wuustwezel tot 8.650 vleesvarkens en titel: een mestverwerkingsinstallatie met een capaciteit van 18.000 ton/jaar rapportnummer: M16LOBE1_kennisgeving/ontwerpMER opdrachtgever: Lobergh bvba Kleinenberg 23 2990 Wuustwezel contactpersoon: Van Den Bergh Dirk ([email protected]) ) opdrachtnemer: eco-scan bvba Industrieweg 114H 9032 GENT tel +32 9 265 74 06 – fax +32 9 265 74 05 [email protected] – www.eco-scan.be contactpersoon/auteur(s): Marjan Speelmans e-mail: [email protected] datum: februari 2017 goedgekeurd: voor eco-scan bvba door ir. Toon Van Elst, zaakvoerder copyright: © 2017, eco-scan bvba eco-scan bvba M16LOBE1_kennisgeving / ontwerp-MER 2 Colofon Opdrachtgever: Lobergh bvba Veldvoort 40 2990 Wuustwezel KBO: 0877.960.163 VE: 2.215.301.242 Projectlocatie Kleinenberg 23 2990 Wuustwezel Opstellers rapport: Studiebureau eco-scan bvba Industrieweg 114H 9032 Gent (Wondelgem) M.e.r.-deskundigen Discipline lucht Nico Raes (OLFASCAN nv) Disciplines bodem en water Peter Hermans (DLV Belgium CVBA) Coördinatie en Discipline fauna en flora Marjan Speelmans (eco-scan bvba) Medewerker(s) MER Kim Van Elsen, medewerker discipline geluid eco-scan bvba M16LOBE1_kennisgeving / ontwerpMER 3 Inhoudsopgave Colofon .................................................................................................................. -

PCR SARS-Cov-2 Voor Vertrek Op Reis

PCR SARS-CoV-2 voor vertrek op reis Reizen naar het buitenland wordt nog steeds afgeraden. Personen die zich toch naar het buitenland begeven dienen zich bewust te zijn van de mogelijk evolutieve wettelijke bepalingen in het land van vertrek en het land van aankomst. Het is de verantwoordelijkheid van iedere individuele reiziger om zich volledig en voorafgaandelijk te informeren betreffende de geldende regels inzake internationale reizen en deze regels strikt toe te passen. Sommige reisbestemmingen vereisen een Engelstalig attest met negatief resultaat voor SARS-CoV-2 met RT-PCR . Het laboratorium van AZ Klina kan u deze dienstverlening aanbieden zolang er geen restricties worden opgelegd door de Belgische overheid. Staalafname is enkel en alleen mogelijk op afspraak . 1) Hoe kan men een afspraak bekomen? A. Via de (huis)arts Uw (huis)arts kan een afspraak voor u inplannen op één van de afnamepunten (Brasschaat/ Kalmthout). In dit geval is uw arts verantwoordelijk voor het bezorgen van een aanvraag- formulier/elektronisch equivalent (E-form) aan de patiënt of rechtstreeks aan het afnamepunt. Op het aanvraagformulier dient duidelijk aangegeven te worden dat het een test betreft voor reisdoeleinden, alsook de datum van vertrek. Tevens kan uw (huis)arts zelf de staalafname verzorgen indien gewenst. Het staal wordt vervolgens samen met een aanvraagformulier/elektronisch equivalent (E-form) bezorgd aan het laboratorium. B. Via de website Alle reizigers uit onze regio (Brasschaat, Brecht, Sint-Job in ‘t Goor, Essen, Kalmthout, Kapellen, Wuustwezel, Stabroek, Hoevenen, Schoten, Malle, Zoersel, Schilde en Ekeren) met een Belgisch rijksregisternummer wordt gevraagd om zelf een afspraak in te boeken op de gewenste datum/tijdstip op één van onze afnamepunten naar keuze (Brasschaat of Kalmthout) via https://noordrand.testcovid.be/ . -

Bijlagen.Pdf

Bijlagen Inhoud Bijlage 1: Het hoe en waarom van een ruimtelijk structuurplan..........................................................7 1.1. Het wetgevend kader.........................................................................................................................7 1.1.1. Het decreet van 18 mei 1999 ...........................................................................................................7 1.1.2. Omzendbrief RO 97/02 over het gemeentelijk structuurplanningsproces........................................7 1.2. Aanpak structuurplanning Wuustwezel..........................................................................................8 1.2.1. Planningsmethodiek .........................................................................................................................8 1.2.2. Communicatie en organisatie.........................................................................................................10 Bijlage 2: Verbanden met het Ruimtelijk Structuurplan Vlaanderen (RSV)......................................14 2.1. Deelstructuren in het RSV ..............................................................................................................14 2.2. Buitengebied....................................................................................................................................14 2.2.1. Doelstellingen voor het buitengebied .............................................................................................14 2.2.2. Functies in het buitengebied ..........................................................................................................15 -

Gemeentelijk Mobiliteitsplan Fase 3: Beleidsplan

Provincie: Antwerpen Gemeente: Hoogstraten Dossiernr: 303.98 april – december 2002 - Hasselt stad Hoogstraten: gemeentelijk mobiliteitsplan Fase 3: Beleidsplan Opdrachtgever: Stadsbestuur Hoogstraten Vrijheid 149 2320 Hoogstraten Libost-Groep nv. raadgevend ingenieurs Herckenrodesingel 101 3500 Hasselt Domeinstraat 11A 3010 Kessel-Lo tel: 011/26.08.70 fax: 011/26.08.80 tel: 016/89.57.83 fax: 016/89.34.40 email: [email protected] MOBILITEITSPLAN STAD HOOGSTRATEN deelrapport: fase 3: beleidsplan In opdracht van het stadsbestuur van Hoogstraten dossiernummer : 304.97 / 00-042 april – december 2002 Herckenrodesingel 101 3500 Hasselt telefoon: 011-26 08 70 telefax: 011-26 08 80 e-mail: [email protected] INHOUDSOPGAVE 1 INLEIDING........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Het mobiliteitsplan...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Samenvatting oriëntatiefase....................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Samenvatting synthesenota ....................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Keuze voorkeursscenario........................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Opbouw beleidsplan.................................................................................................................. -

Erfgoedroute Wuustwezel

Erfgoedroute Wuustwezel Een erfgoedroute in Wuustwezel Wuustwezel is een mooie plattelandsgemeente waar fietsers en wandelaars genieten van het prachtige natuurschoon dat de gemeente rijk is. Geboren Wuustwezelnaars en toeristen die de gemeente alsmaar meer aandoen, genieten van de vele wandelingen en fietstochten doorheen de Wuustwezelse natuur die door Toerisme Wuustwezel worden aangeboden. Maar Wuustwezel kan niet alleen bogen op haar mooie natuur. De gemeente Wuustwezel en haar gehuchten hebben ook een rijke geschiedenis. De kerk van Wuustwezel-centrum bijvoorbeeld werd al in bronnen vermeld in 1257 en ook de deelgemeente Loenhout, één van de oudste dorpen uit de Noorderkempen, werd reeds in verschillende documenten vernoemd in het begin van de dertiende eeuw. De rijke geschiedenis van de gemeente Wuustwezel weerspiegelt zich in het bewaarde onroerende erfgoed dat verspreid ligt over de verschillende gehuchten. Dat het Wuustwezelse onroerend erfgoed de gemeente een grote meerwaarde geeft, is ook het gemeentebestuur niet ontgaan. In haar recente cultuurbeleidsplan werd daarom veel aandacht besteed aan de inventarisatie en preservatie van het erfgoed in de gemeente. Om de interessante geschiedenis van Wuustwezel onder de aandacht te brengen en om te wijzen op de noodzaak om dit erfgoed te beschermen, zijn Walter Liégeois – fotograaf en verzamelaar van oude foto‟s en postkaarten – en Jan De Meester – voorzitter van heemkundekring Wesalia II en afgevaardigde van de erfgoedverenigingen in de gemeentelijke cultuurraad – ingegaan op een vraag van de lagere scholen in de gemeente om voor hun leerlingen een educatieve erfgoedroute uit te stippelen. Zij hebben daarbij een route geactualiseerd die in 2002 door de lokale heemkundige kring was samengesteld naar aanleiding van Erfgoeddag. -

Impact of Precipitation Trends and the North Atlantic Oscillation on Phreatic Water Levels in Low Belgium

GEOLOGICA BELGICA (2013) 16/3: 157-163 Impact of precipitation trends and the North Atlantic Oscillation on phreatic water levels in Low Belgium Marc VAN CAMP & Kristine WALRAEVENS Ghent University, Laboratory for Applied Geology and Hydrogeology, Krijgslaan 281-S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium ABSTRACT. A set of 10 representative multi-decade long time series of piezometric levels of phreatic aquifers were selected in different parts of Low Belgium to investigate correlations between groundwater levels, precipitation rates and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index. Correlations between piezometric levels and precipitation rates are always high and significant at the 5% level for all series. A direct relation between groundwater levels and the NAO is only possible if there is a correlation with aquifer recharge, which in north Belgium is limited to the winter period. Correlation between monthly precipitation and monthly NAO indices are highly temporal, with two distinct periods during which the correlation is significant at the 5% level. In summer (July and August) there is a negative correlation, in winter time (December and January) a positive one. As in summer aquifer recharge is negligible, only the winter NAO index can have an impact on groundwater levels. Of the ten investigated series, only two have a significant correlation at the 5% level, between piezometric levels and the December-January NAO values. Both wells lie in the same region, in the upper part of the lithologically heterogeneous Campine Complex. The local hydrogeological conditions here seem to increase sensitivity to winter NAO modus. KEYWORDS: groundwater, piezometric levels, time series, aquifer recharge, correlation, winter NAO modus 1. -

Athlete's Guide

1 ATHLETE’S GUIDE 2018 Wuustwezel ETU Sprint Triathlon European Cup 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 3 1.1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.2. KEY DATES 3 1.3. KEY CONTACTS 3 1.4. CONTACT DETAILS 3 2. VENUE 4 2.1. RACE VENUE 4 2.2. COURSE FAMILIARIZATION 4 2.3. ATHLETE’S LOUNGE 4 2.4. ELITE ATHLETES’ RACE PACKAGE 4 2.5. DOPING CONTROL 4 2.6. SECURITY 4 2.7. LOC OFFICE 4 3. ACCOMMODATION 5 4. TRANSFER AND TRANSPORT 5 5. ATHELETE’S SERVICES 7 5.1. SWIM AND BIKE TRAINING 7 5.2. MEDICAL SERVICES 8 5.3. BIKE MECHANICAL SERVICE 8 6. COMPETITION SCHEDULE 9 6.1. ELITE WOMEN 9 6.2. ELITE MEN 9 6.3. COMPETITION RULES 9 6.4. ATHLETE’S BRIEFING 9 6.5. TIMING CHIPS 9 6.6. RESULTS 10 6.7. PROTEST & APPEALS 10 7. ACCREDITATION 10 8. COURSE MAPS 10 3 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Athlete’s Guide is to ensure that all athletes, coaches and Team Leaders are well informed about all procedures concerning the Event. The LOC ensures that the information contained in this Guide is correct and up‐to‐date as of the production date. However, athletes, coaches and Team Leaders are advised to check with the event office regarding any changes in information included in this guide. 1.2. KEY DATES Briefing: Friday, June 22, 18h (local time) Bike course familiarization: (to be announced) Swim course familiarization: (following the bike course familiarization) Race start women: Saturday, June 23, 18:00h Race start men: Saturday, June 23, 20:00h The athlete briefing is at 18h on Friday, June 22. -

BIJLAGE 1 Afdeling Antwerpen Openbare Procedure D.D

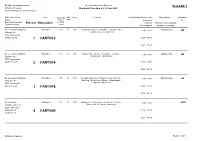

De Lijn - Leerlingenvervoer Overzicht aan te besteden ritten BIJLAGE 1 Afdeling Antwerpen Openbare Procedure d.d. 12 mei 2020 Grotehondstraat 58, 2018 Antwerpen Beherende school Zone Dagelijks Min. Freq.Reisweg Beschikbaarheid (van - tot) Opmerkingen Elektrische Adres traject cap. 's morgens lift Postcode Gemeente Perceel Ritnummer sch/sch 's avonds eventuele max. capaciteit in km Telefoonnummer woensdagmid bijzondere uitrusting De Leerexpert Dullingen Antwerpen 120 22 D10 Vestiging Kalmthout : Kalmthout - Schilde - Sint- 6:00 - 8:30 bagageruimte JA Dullingen 46 Lenaarts - Essen - Kalmthout 2930 Brasschaat 0485/61 56 09 1 1/ANT/012 15:25 - 18:00 15:25 - 18:00 De Leerexpert Dullingen Antwerpen 115 30 D10 Brasschaat - Zoersel - Westmalle - Schilde - 6:00 - 8:30 bagageruimte JA Dullingen 46 Wuustwezel - Brasschaat 2930 Brasschaat 0485/61 56 09 2 1/ANT/014 15:25 - 18:00 15:25 - 18:00 De Leerexpert Dullingen Antwerpen 160 30 D10 Vestiging Kalmthout : Kalmthout - Lier - Kontich - 6:00 - 8:45 bagageruimte JA Dullingen 46 Berchem - Borgerhout - Ekeren - Brasschaat - Kapellen - Kalmthout 2930 Brasschaat 0485/61 56 09 3 1/ANT/046 15:25 - 18:15 15:25 - 18:15 De Leerexpert Antwerpen 60 22 D10 Antwerpen - Wommelgem - Borsbeek - Deurne - 6:30 - 8:35 - NEE August Leyweg 10 Borgerhout - Berchem - Antwerpen 2020 Antwerpen 03/242 01 30 4 1/ANT/049 15:25 - 17:30 03/242 01 20 12:35 - 14:30 FOR/AL/10.1/02/003 Pagina 1 van 9 De Lijn - Leerlingenvervoer Overzicht aan te besteden ritten BIJLAGE 1 Afdeling Antwerpen Openbare Procedure d.d. 12 mei 2020 Grotehondstraat 58, 2018 Antwerpen Beherende school Zone Dagelijks Min.