The Angel Controversy: an Archival Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016 Denis Murphy, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted for the award of PhD January 2017 School of Communications Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr. Roddy Flynn I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD, is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 81407637 Date: _______________ 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 12 The research problem ................................................................................................................................. 14 Local history, local Hollywood? ............................................................................................................... 16 Methodology and data sources ................................................................................................................ 18 Outline of chapters ....................................................................................................................................... -

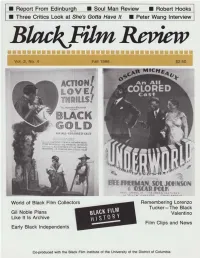

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Julianne Moore Stephen Dillane Eddie Redmayne

JULIANNE MOORE STEPHEN DILLANE EDDIE REDMAYNE ELENA ANAYA Directed By Tom Kalin UNAX UGALDE Screenplay by Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M. L. Aronson BELÉN RUEDA HUGH DANCY Julianne Moore, Stephen Dillane, Eddie Redmayne Elena Anaya, Unax Ugalde, Belén Rueda, Hugh Dancy CANNES 2007 Directed by Tom Kalin Screenplay Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M.L Aronson FRENCH / INTERNATIONAL PRESS DREAMACHINE CANNES 4th Floor Villa Royale 41 la Croisette (1st door N° 29) T: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 35 WORLD SALES F: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 70 DREAMACHINE CANNES Magali Montet 2, La Croisette, 3rd floor M : + 33 (0) 6 71 63 36 16 T : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 64 58 E: [email protected] F : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 62 26 Gordon Spragg M : + 33 (0) 6 75 25 97 91 LONDON E: [email protected] 24 Hanway Street London W1T 1UH US PRESS T : + 44 (0) 207 290 0750 INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY F : + 44 (0) 207 290 0751 info@hanwayfilms.com CANNES Jeff Hill PARIS M: + 33 (0)6 74 04 7063 2 rue Turgot email: [email protected] 75009 Paris, France T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 Jessica Uzzan F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 M: + 33 (0)6 76 19 2669 [email protected] email: [email protected] www.dreamachinefilms.com Résidence All Suites – 12, rue Latour Maubourg T : + 33 (0) 4 93 94 90 00 SYNOPSIS “Savage Grace”, based on the award winning book, tells the incredible true story of Barbara Daly, who married above her class to Brooks Baekeland, the dashing heir to the Bakelite plastics fortune. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

Papers of Gemma Hussey P179 Ucd Archives

PAPERS OF GEMMA HUSSEY P179 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 © 2016 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement ix CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xi Language xi Finding Aid xi DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note xi ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xi Published Material xi iii CONTEXT Biographical History Gemma Hussey nee Moran was born on 11 November 1938. She grew up in Bray, Co. Wicklow and was educated at the local Loreto school and by the Sacred Heart nuns in Mount Anville, Goatstown, Co. Dublin. She obtained an arts degree from University College Dublin and went on to run a successful language school along with her business partner Maureen Concannon from 1963 to 1974. She is married to Dermot (Derry) Hussey and has one son and two daughters. Gemma Hussey has a strong interest in arts and culture and in 1974 she was appointed to the board of the Abbey Theatre serving as a director until 1978. As a director Gemma Hussey was involved in the development of policy for the theatre as well as attending performances and reviewing scripts submitted by playwrights. In 1977 she became one of the directors of TEAM, (the Irish Theatre in Education Group) an initiative that emerged from the Young Abbey in September 1975 and founded by Joe Dowling. It was aimed at bringing theatre and theatre performance into the lives of children and young adults. -

Not a Cinematic Hair out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) As Evidenced Through Haircuts in the Rc Ying Game Allen Herring III

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-8-2011 Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game Allen Herring III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Herring, Allen III. "Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III Bachelors – English Bachelors – Economics THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2010 iii ©2010, Allen Herring III iv Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of -

IFB Locations Brochure 2017

1 Irish Film Board — Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board (IFB) is the national development agency for the Irish film, television and animation industry, supporting and developing talent, creativity and enterprise. It provides development, production and distribution funding for writers, directors and production companies across these sectors. The IFB supports Ireland as a dynamic and world-class location for international production by promoting Irish tax incentives, our excellent skilled crew base, and our well-established studio and technical infrastructure. The IFB also supports the development of skills and training in live-action, animation, VFX and interactive content through Screen Training Ireland. Contents — ‘Dublin and its surrounds were the perfect location for our London-set Dickensian period piece. The range of settings, architecture and the ease of access to locations was in my experience unparalleled.’ Introduction 06 Bharat Nulluri, Director Ireland’s Tax Credit 10 The Man Who Invented Christmas Ireland and International Co-Production 14 The Irish Producer 16 Location, Location, Location 20 Film Studios 24 Post Production 28 VFX 30 Animation 34 IFB Location Services 36 Funding Sources 38 Other Financial Incentives 39 Support Networks, Guilds and Associations 42 King’s Inns, Henrietta Street, Dublin 02 03 Grand Canal Dock, Dublin 04 05 Introduction — ‘Ireland has become an important part of Star Wars history.’ Candice Campos, Vice President, Physical Production, Lucasfilm Ireland has a long-standing, World-class film is produced in diverse and exceptionally rich Ireland year after year. Recent culture of bringing stories completed projects include to the screen. It has long Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: been associated with great Episode VIII–The Last Jedi, filmmaking, from the feisty, Farhad Safinia’sThe Professor passionate romance played and the Madman and Nora by John Wayne and Maureen Twomey’s animated feature O’Hara in John Ford’s much- film,The Breadwinner. -

Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20Th Century

1632 MARKET STREET SAN FRANCISCO 94102 415 347 8366 TEL For immediate release Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century Curated by Ralph DeLuca July 21 – September 24, 2016 FraenkelLAB 1632 Market Street FraenkelLAB is pleased to present Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century, curated by Ralph DeLuca, from July 21 through September 24, 2016. Beginning with the earliest public screenings of films in the 1890s and throughout the 20th century, the design of eye-grabbing posters played a key role in attracting moviegoers. Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters at FraenkelLAB focuses on seldom-exhibited posters that incorporate photography to dramatize a variety of film genres, from Hollywood thrillers and musicals to influential and experimental films of the 1960s-1990s. Among the highlights of the exhibition are striking and inventive posters from the mid-20th century, including the classic films Gilda, Niagara, The Searchers, and All About Eve; Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho; and B movies Cover Girl Killer, Captive Wild Woman, and Girl with an Itch. On view will be many significant posters from the 1960s, such as Russ Meyer’s cult exploitation film Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up; a 1968 poster for the first theatrical release of Un Chien Andalou (Dir. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, 1928); and a vintage Japanese poster for Buñuel’s Belle de Jour. The exhibition also features sensational posters for popular movies set in San Francisco: the 1947 film noir Dark Passage (starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall); Steve McQueen as Bullitt (1968); and Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry (1971). -

80S 90S Hand-Out

FILM 160 NOIR’S LEGACY 70s REVIVAL Hickey and Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972) The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975) Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975) The Drowning Pool (Stuart Rosenberg, 1975) The Big Sleep (Michael Winner, 1978) RE- MAKES Remake Original Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981) Postman Always Rings Twice (Garnett, 1946) Breathless (Jim McBride, 1983) Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1959) Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984) Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) The Morning After (Sidney Lumet, 1986) The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953) No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1987) The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948) DOA (Morton & Jankel, 1988) DOA (Rudolf Maté, 1949) Narrow Margin (Peter Hyams, 1988) Narrow Margin (Richard Fleischer, 1951) Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991) Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962) Night and the City (Irwin Winkler, 1992) Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) Kiss of Death (Barbet Schroeder 1995) Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947) The Underneath (Steven Soderbergh, 1995) Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949) The Limey (Steven Soderbergh, 1999) Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) The Deep End (McGehee & Siegel, 2001) Reckless Moment (Max Ophuls, 1946) The Good Thief (Neil Jordan, 2001) Bob le flambeur (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1955) NEO - NOIRS Blood Simple (Coen Brothers, 1984) LA Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986) Lost Highway (David -

Ibec 2006 (Pdf)

Film & Television Production in Ireland Audiovisual Federation Review 2006 IBEC AUDIOVISUAL FEDERATION An affiliate association within IBEC | the Irish Business and Employers Confederation Confederation House, 84/86 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin 2 Tel: + 353 - 1 - 6601528, Fax: + 353 - 1 - 6381528 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ibec.ie/avf An affiliate association within IBEC | the Irish Business and Employers Confederation www.ibec.ie AUDIO VISUAL FEDERATION REVIEW 2006 Film & Television Production in Ireland Audiovisual Federation Review 2006 IBEC Audiovisual Federation The Audiovisual Federation consists of IBEC member companies involved in Ireland’s audiovisual industry. These include broadcasters, producers, animation studios, facilities and other organisations supporting the sector. The Federation has a number of objectives designed to support Ireland’s audiovisual production and distribution industry. These include promotion of the sector, representing the views of members to relevant bodies and submitting the industry view on relevant policy. The Audiovisual Federation maintains an economic database for the Irish audiovisual production sector and publishes the results in an annual report with an economic analysis on the benefits of the audiovisual sector to the Irish economy. In order to sustain the growth and development within the sector during the last number of years the Federation has sought internationally competitive financial incentives and international co-production treaties. Together with Enterprise Ireland