The Postcolonial Graham Greene in Neil Jordan's the End Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Philosophy Goes to the Movies

PHILOSOPHY GOES TO THE MOVIES ‘Philosophy Goes to the Movies is very clearly and engagingly written. It has a particular claim on the attention of those preparing students for a systematic study of philosophy, one that distinguishes it from any other introductory book I know of.’ Stephen Mulhall, University of Oxford ‘I think this is an excellent text. Falzon is in control of his material. He writes clearly and at a level that undergraduates can understand. He seems as comfortable describing films as he is explaining the nature of a philosophical problem. It will make an outstanding text to use in introductory philosophy classes.’ Thomas Wartenburg, Mount Holyoke College, USA Philosophy Goes to the Movies is a new kind of introduction to philosophy that makes use of film to help us understand philosophical ideas and positions. Drawing on art- house movies like Cinema Paradiso and Hollywood blockbusters such as The Matrix, Christopher Falzon introduces and discusses central areas of philosophical concern, including: • the theory of knowledge • the self and personal identity • ethics • social and political philosophy • science and technology • critical thinking. Falzon draws from the ideas of a diverse selection of thinkers, from Plato and Descartes to Marcuse and Foucault. Ideal for the beginner, this book guides the student through philosophy using lively and illuminating cinematic examples including Total Recall, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Antz and Wings of Desire. It will also appeal to anyone interested in the philosophical dimensions of cinema. Christopher Falzon is Lecturer in Philosophy at Newcastle University, Australia. He is the author of Foucault and Social Dialogue (Routledge, 1998). -

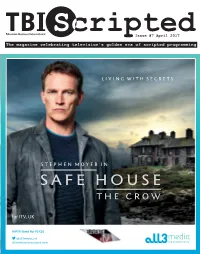

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

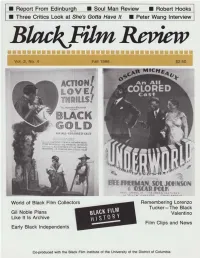

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Julianne Moore Stephen Dillane Eddie Redmayne

JULIANNE MOORE STEPHEN DILLANE EDDIE REDMAYNE ELENA ANAYA Directed By Tom Kalin UNAX UGALDE Screenplay by Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M. L. Aronson BELÉN RUEDA HUGH DANCY Julianne Moore, Stephen Dillane, Eddie Redmayne Elena Anaya, Unax Ugalde, Belén Rueda, Hugh Dancy CANNES 2007 Directed by Tom Kalin Screenplay Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M.L Aronson FRENCH / INTERNATIONAL PRESS DREAMACHINE CANNES 4th Floor Villa Royale 41 la Croisette (1st door N° 29) T: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 35 WORLD SALES F: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 70 DREAMACHINE CANNES Magali Montet 2, La Croisette, 3rd floor M : + 33 (0) 6 71 63 36 16 T : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 64 58 E: [email protected] F : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 62 26 Gordon Spragg M : + 33 (0) 6 75 25 97 91 LONDON E: [email protected] 24 Hanway Street London W1T 1UH US PRESS T : + 44 (0) 207 290 0750 INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY F : + 44 (0) 207 290 0751 info@hanwayfilms.com CANNES Jeff Hill PARIS M: + 33 (0)6 74 04 7063 2 rue Turgot email: [email protected] 75009 Paris, France T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 Jessica Uzzan F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 M: + 33 (0)6 76 19 2669 [email protected] email: [email protected] www.dreamachinefilms.com Résidence All Suites – 12, rue Latour Maubourg T : + 33 (0) 4 93 94 90 00 SYNOPSIS “Savage Grace”, based on the award winning book, tells the incredible true story of Barbara Daly, who married above her class to Brooks Baekeland, the dashing heir to the Bakelite plastics fortune. -

Not a Cinematic Hair out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) As Evidenced Through Haircuts in the Rc Ying Game Allen Herring III

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-8-2011 Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game Allen Herring III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Herring, Allen III. "Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III Bachelors – English Bachelors – Economics THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2010 iii ©2010, Allen Herring III iv Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of -

Talking Theatre Extract

Richard Eyre TALKING THEATRE Interviews with Theatre People Contents Introduction xiii Interviews John Gielgud 1 Peter Brook 16 Margaret ‘Percy’ Harris 29 Peter Hall 35 Ian McKellen 52 Judi Dench 57 Trevor Nunn 62 Vanessa Redgrave 67 NICK HERN BOOKS Fiona Shaw 71 London Liam Neeson 80 www.nickhernbooks.co.uk Stephen Rea 87 ix RICHARD EYRE CONTENTS Stephen Sondheim 94 Steven Berkoff 286 Arthur Laurents 102 Willem Dafoe 291 Arthur Miller 114 Deborah Warner 297 August Wilson 128 Simon McBurney 302 Jason Robards 134 Robert Lepage 306 Kim Hunter 139 Appendix Tony Kushner 144 John Johnston 313 Luise Rainer 154 Alan Bennett 161 Index 321 Harold Pinter 168 Tom Stoppard 178 David Hare 183 Jocelyn Herbert 192 William Gaskill 200 Arnold Wesker 211 Peter Gill 218 Christopher Hampton 225 Peter Shaffer 232 Frith Banbury 239 Alan Ayckbourn 248 John Bury 253 Victor Spinetti 259 John McGrath 266 Cameron Mackintosh 276 Patrick Marber 280 x xi JOHN GIELGUD Would you say the real father—or mother—of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company is Lilian Baylis? Well, I think she didn’t know her arse from her elbow. She was an extraordinary old woman, really. And I never knew anybody who knew her really well. The books are quite good about her, but except for her eccentricities there’s nothing about her professional appreciation of Shakespeare. She had this faith which led her to the people she needed. Did she choose the actors? I don’t think so. She chose the directors. John Gielgud Yes, she had a very difficult time with them. -

Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20Th Century

1632 MARKET STREET SAN FRANCISCO 94102 415 347 8366 TEL For immediate release Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century Curated by Ralph DeLuca July 21 – September 24, 2016 FraenkelLAB 1632 Market Street FraenkelLAB is pleased to present Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century, curated by Ralph DeLuca, from July 21 through September 24, 2016. Beginning with the earliest public screenings of films in the 1890s and throughout the 20th century, the design of eye-grabbing posters played a key role in attracting moviegoers. Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters at FraenkelLAB focuses on seldom-exhibited posters that incorporate photography to dramatize a variety of film genres, from Hollywood thrillers and musicals to influential and experimental films of the 1960s-1990s. Among the highlights of the exhibition are striking and inventive posters from the mid-20th century, including the classic films Gilda, Niagara, The Searchers, and All About Eve; Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho; and B movies Cover Girl Killer, Captive Wild Woman, and Girl with an Itch. On view will be many significant posters from the 1960s, such as Russ Meyer’s cult exploitation film Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up; a 1968 poster for the first theatrical release of Un Chien Andalou (Dir. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, 1928); and a vintage Japanese poster for Buñuel’s Belle de Jour. The exhibition also features sensational posters for popular movies set in San Francisco: the 1947 film noir Dark Passage (starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall); Steve McQueen as Bullitt (1968); and Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry (1971). -

80S 90S Hand-Out

FILM 160 NOIR’S LEGACY 70s REVIVAL Hickey and Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972) The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975) Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975) The Drowning Pool (Stuart Rosenberg, 1975) The Big Sleep (Michael Winner, 1978) RE- MAKES Remake Original Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981) Postman Always Rings Twice (Garnett, 1946) Breathless (Jim McBride, 1983) Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1959) Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984) Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) The Morning After (Sidney Lumet, 1986) The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953) No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1987) The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948) DOA (Morton & Jankel, 1988) DOA (Rudolf Maté, 1949) Narrow Margin (Peter Hyams, 1988) Narrow Margin (Richard Fleischer, 1951) Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991) Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962) Night and the City (Irwin Winkler, 1992) Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) Kiss of Death (Barbet Schroeder 1995) Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947) The Underneath (Steven Soderbergh, 1995) Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949) The Limey (Steven Soderbergh, 1999) Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) The Deep End (McGehee & Siegel, 2001) Reckless Moment (Max Ophuls, 1946) The Good Thief (Neil Jordan, 2001) Bob le flambeur (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1955) NEO - NOIRS Blood Simple (Coen Brothers, 1984) LA Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986) Lost Highway (David -

PRESS NOTES March 2019

PRESS NOTES March 2019 INFORMION 114 Minutes Ratio: 2:35 color Red Dragon DCP • AUDIO: 5.1 PRESS Emma Griffiths [email protected] PRODUCERS Larry Fessenden [email protected] Chadd Harbold [email protected] Jenn Wexler [email protected] PRINT TRAFFIC GLASS EYE PIX 172 East 4th Street #5F New York, NY 10009 WEBSITES A film by Larry Fessenden glasseyepix.com depravedfilm.com GLASS EYE PIX & FORAGER FILM COMPANY present DAVID CALL JOSHUA LEONARD and ALEX BREAUX "DEPRAVED" ANA KAYNE MARIA DIZZIA CHLOË LEVINE OWEN CampBELL and ADDISON TIMLIN cinematography CHRIS SKOTCHDOPOLE James SIEWERT production design APRIL LASKY costume design SARA ELISABETH LOTT makeup effects GERNER & SPEARS EFFECTS visual effects james SIEWERT music WILL bates sound design JOHN MOROS mix TOM EFINGER executive producers JOE SWANBERG EDWIN LINKER PETER GILBERT co-executive producerS andrew MER SIG DE MIGUEL STEPHEN VINCENT co-producer LIZZ ASTOR producers CHADD HARBOLD JENN WEXLER writer director editor producer LARRY FESSENDEN (c) 2019 DEPRAVED PRODUCTIONS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. A Glass Eye Pix COSTUME Lucy Double POST PICTURE "depRAVEd" Forager Film Company assistant costume designer ASHLEY MORGAN BLOOM Finishing Written and Performed by production ARIS BORDO Polidori Double CONTACT POST UNWANTED HOUSEGUEST wardrobe supervisor COLIN VAN WYE colorist publisher Tavistock Records CREW ALANNA GOODMAN Child Singers BLASE THEODORE BELLA MAGGIO "Wheels on the Bus" writer director editor Uniforms Edit and Online Facilities LARRY FESSENDEN KAUFMAN’S ARMY & NAVY JOEY MAGGIO THE STATION Performed by NIA AMALIA MOROS UNWANTED HOUSEGUEST producers additional animation LARRY FESSENDEN MAKEUP TV Voices BEN DUFF JAMES LE GROS "Pleasant Street" CHADD HARBOLD hair and makeup dept. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Bernard Dukore

What's New . At Least in Part1 Bernard F. Dukore [Dr. Bernard F. Dukore's Fellows Address was given at the ATA Convention in San Francisco, August 14, 1984. His Note #1 provides information about its publication in considerably altered form under the title, "Newer Peter Barnes, with Links to the Past," in Essays in Theatre, 5 (November 1986), pp. 47-59, and gives a rationale for updating the Address for inclusion here. Ed.] Copyright 1986, 1994 by Bernard F. Dukore © On the night of February 22nd, 1984, I decided that instead of going to the movies I would catch up on my reading. Too many books and periodicals were on my desk, looking at me in a way I thought reproachful. Among them was the December 1983 Theatre Journal, which contained Helen Krich Chinoy's "Notes" on the American theatre of the 1930s, her Fellows Address at the ATA Convention in August 1982. It was the first work that I read. The next morning, February 23rd, I received a phone call from Tony Distler, inviting me to give the Fellows Address at this convention. I don't know if there's a causal connection between the two, but if there is, you can cheer up, because the alternative might have been worse. You see, the movie I had considered going to see that night was Testament.2 Like my predecessors, I was told that I was free to pick any subject I liked, to give any kind of talk I chose. Oh, Lord! As Elmer Rice, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Peter Barnes, among others, have dramatized, freedom can be terrifying.