Neil Jordan's Michael Collins and an Anti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Copy of Copy of Copy of Streetwear Creative Wide Presentation

"Life's most persistent and urgent question is; what are you doing for others?" -MLK OUR VISION For over a decade, MDC has helped establish rewarding relationships between thousands of individuals, businesses and charities who care deeply about the well-being of others and the community. Through our work (video production, event planning & consulting) we want to share stories that matter, organize events that build bridges, highlight extraordinary individuals, create simple and effective ways of giving back, and act as professional matchmakers. Our mission has always been to connect the people who want to help with the people who need help the most. From the start, we've witnessed heartbreaking scenarios where trauma and hardship causes a child or family to feel isolated and hopeless. Despite what we're taught, time is more precious than gold and we strive to make every day, hour and minute count. The world does not stop when tragedy strikes; but good people can and do. We enlist the help of caregivers across every business sector around the globe and rely on them to help us create special moments in time that bring hope and joy to those suffering through hardship. We've created an Active Response Team; an unofficial team of do-gooders who are willing to step up to the plate when needed. And just like the word "team" signifies, together everyone achieves more. MDC works by cause, not by client -- and in doing so, it allows us to foster collaboration and look after the interests of all involved. The impact we make by working together is more powerful and far-reaching than most individuals can achieve on their own. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

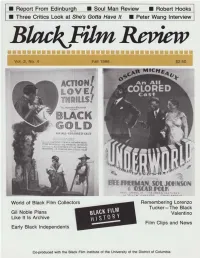

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Sir John Lavery's the Dentist

Sir John Lavery’s The Dentist IN BRIEF • Sir John Lavery’s portrait of The Dentist (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) is an GENERAL unusual departure for a painter renowned (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) for his portraits of the contemporary celebrities. K. McConkey1 • It shows its subject in action. His patient, Hazel Lavery, one of the great beauties of the day, is partially obscured. • Lavery’s depiction of dentists’ equipment gives us an almost unprecedented view of a surgery of the 1920s. The rise of the dental profession coinciding with the invention and rapid spread of photography means that there are very few paintings of dentists in action. The present article describes Sir John Lavery’s unusual depiction of The Dentist (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) in which the conventions of contemporary society portraiture are set aside. The resulting canvas has much to tell us about the up-to-date equipment used in a surgery of the late twenties by a successful practitioner who pioneered the use of X‑rays. In 1929, Sir John Lavery exhibited one of in 1926, one commentator dubbed the com- His career blossomed after he moved his most striking portraits – The Dentist missions Lavery received in New York, Long to London and purchased 5 Cromwell (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) (Fig. 1). Island and Boston as portraits of ‘million- Famed for his pictures of society host- aires surrounded by their millions’.2 esses, political leaders and members of the The artist was 70 when this new genre Royal Family, Lavery had recently devel- emerged. -

Julianne Moore Stephen Dillane Eddie Redmayne

JULIANNE MOORE STEPHEN DILLANE EDDIE REDMAYNE ELENA ANAYA Directed By Tom Kalin UNAX UGALDE Screenplay by Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M. L. Aronson BELÉN RUEDA HUGH DANCY Julianne Moore, Stephen Dillane, Eddie Redmayne Elena Anaya, Unax Ugalde, Belén Rueda, Hugh Dancy CANNES 2007 Directed by Tom Kalin Screenplay Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M.L Aronson FRENCH / INTERNATIONAL PRESS DREAMACHINE CANNES 4th Floor Villa Royale 41 la Croisette (1st door N° 29) T: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 35 WORLD SALES F: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 70 DREAMACHINE CANNES Magali Montet 2, La Croisette, 3rd floor M : + 33 (0) 6 71 63 36 16 T : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 64 58 E: [email protected] F : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 62 26 Gordon Spragg M : + 33 (0) 6 75 25 97 91 LONDON E: [email protected] 24 Hanway Street London W1T 1UH US PRESS T : + 44 (0) 207 290 0750 INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY F : + 44 (0) 207 290 0751 info@hanwayfilms.com CANNES Jeff Hill PARIS M: + 33 (0)6 74 04 7063 2 rue Turgot email: [email protected] 75009 Paris, France T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 Jessica Uzzan F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 M: + 33 (0)6 76 19 2669 [email protected] email: [email protected] www.dreamachinefilms.com Résidence All Suites – 12, rue Latour Maubourg T : + 33 (0) 4 93 94 90 00 SYNOPSIS “Savage Grace”, based on the award winning book, tells the incredible true story of Barbara Daly, who married above her class to Brooks Baekeland, the dashing heir to the Bakelite plastics fortune. -

Download Films / Movies Card Game (PDF)

Back to the Future Blade Runner ET 1985 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi Robert Zemeckis (director) Ridley Scott (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Michael J Fox Harrison Ford Dee Wallace Christopher Lloyd The Godfather Harry Potter and the The Exorcist 1972 / crime thriller Philosopher's Stone 1973 / horror Francis Ford Coppola (director) 2001 / fantasy William Friedkin (director) Maron Brando Chris Columbus (director) Ellen Burstyn Al Pacino Daniel Radcliffe Jaws Raiders of the Lost Ark Goldfinger 1975 / thriller 1981 / action / adventure 1964 / spy thriller Steven Spielberg (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Guy Hamilton (director) Roy Scheider Harrison Ford Sean Connery Robert Shaw Jurassic Park Mad Max The Lion King 1993 / sci-fi 1979 / action 1994 / cartoon / musical Steven Spielberg (director) George Miller (director) Roger Allers / Rob Minkoff Sam Neill Mel Gibson (directors) Laura Dern Joanne Samuel Mission Impossible Pirates of the Caribbean: 1996 / spy / action Pinocchio Dead Man's Chest Brian De Palma (director) 1940 2006 / fantasy adventure Tom Cruise cartoon / musical / fantasy Gore Verbinski (director) Paula Wagner Johnny Depp Apocalypse Now Schindler's List The Matrix 1979 / war film 1993 / historical drama 1999 / sci-fi / action Francis Ford Coppola (director) Steven Spielberg (director) The Wachowskis (directors) Marlon Brando Liam Neeson Keanu Reeves Martin Sheen Ralph Fiennes Carrie-Anne Moss Titanic Crazy Rich Asians The Lord of the Rings: The 1997 / disaster / romance 2018 / romantic comedy Fellowship of the Ring James Cameron (director) Jon M. Chu (director) 2001 / fantasy / adventure Leonardo DiCaprio Constance Wu Peter Jackson (director) Kate Winslet Gemma Chan Elijah Wood Ian McKellen Toy Story The Sound of Music The Dark Knight 1995 1965 / musical / drama 2008 / superhero computer-animated comedy Robert Wise (director) Christopher Nolan (director) John Lasseter (director) Julie Andrews Christian Bale Tom Hanks (voice) Christopher Plummer Michael Caine © ELTbase.com 2019. -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

Michael Collins: Patriot Hero Or 41 Counterrevolutionary? Kieran Allen

Michael Collins: patriot hero or 41 counterrevolutionary? Kieran Allen ichael Collins is a Fine Gael hero. Each year its auxiliary forces in Ireland. One of the most famous young Fine Gael members from across the episodes of the Irish War of Independence was the country travel to Béal na Bláth in County Cork elimination of The Cairo Gang. This was an elite unit where Collins was killed by republican forces who were formed by British military intelligence with Mon August 22 1922 during the Civil War. The annual the aim of assassinating republican leaders. They commemoration for Collins features Fine Gael luminaries arrived in Ireland in September 1920 and within weeks or those who share their outlook. In 2018, for example, shot dead a republican activist from Limerick, John the current Minister for Agriculture, Michael Creed, Lynch, as he lay in his bed. They also came close to got carried away with himself and referred to the site of killing Dan Breen and Sean Tracy, the instigators of the Collins’ execution as a ‘Gaelic Calvary’.1 Having recovered Soloheadbeg attack that set off the War of Independence. from this emotional spasm, he went on, like most of his Michael Collins had established his own squad of armed Fine Gael predecessors, to make a banal speech about operatives within the republican forces and gave the current Irish political life, laced with odd quotes from orders for the execution of the Cairo Gang. One of his Collins himself. Fine Gael’s cult of Collins also includes biographers, James MacKay takes up the story. -

Not a Cinematic Hair out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) As Evidenced Through Haircuts in the Rc Ying Game Allen Herring III

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-8-2011 Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game Allen Herring III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Herring, Allen III. "Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place: Examinations in Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The rC ying Game." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III Bachelors – English Bachelors – Economics THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2010 iii ©2010, Allen Herring III iv Not a Cinematic Hair Out of Place Examinations of Identity (Transformation) as Evidenced through Haircuts in The Crying Game BY Allen Herring III ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of -

War of Independence Online Resources

Topic Researchers Online resource General War of Independence https://erinascendantwordpress.wordpress.com/category/irish-war-of-independence/ https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/the-revolution-files https://www.scoilnet.ie/go-to-post-primary/collections/senior-cycle/decade-of-centenaries/the-war-of- independence/ https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/irelands-unhappy-new-year-1920-begins-in-violence- and-disorder Decade of Centenaries | Ulster 1885 - 1925 | Timeline https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes Catalogue - National Library of Ireland 1. Frongoch Prison https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/ frongoch-a-day-in-the-life https://www.museum.ie/The-Collections/Frongoch- and-1916 2. The first Dáil Eireann https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ a-date-with-destiny-the-centenary-of-the-first- d%C3%A1il-1.3762550 https://www.dail100.ie/en http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/ rebellion/the-first-dail-1919/ 3. Lincoln Prison https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/eamon-de- valera-prison-escape 4. Soloheadbeg Ambush https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ soloheadbeg-the-fatal-shots-that-ignited-the-war-of- independence-1.3761334 https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/century/ the-revolution-files/tipperary-1919-the-woman-who- hid-dan-breen-after-soloheadbeg- ambush-1.4036615 5. Informants and Spies http://www.generalmichaelcollins.com/life-times/ rebellion/intelligence-war/ https://www.historyireland.com/volume-25/issue-3- mayjune-2017/spies-informers-beware/ https://stairnaheireann.net/2018/03/12/an- intelligence-card-from-the-irish-war-of- independence/ 6. Knocklong Ambush Knocklong ambush, on May 13th, 1919 involved a 14-minute gun battle Two RIC men killed in ambush in Knocklong | Century Ireland https://stairnaheireann.net/2017/05/13/otd-in-1919- dan-breen-and-sean-treacy-rescue-their-comrade- sean-hogan-from-a-dublin-cork-train-at-knocklong- co-limerick/ 7.