Tangent Map Analysis of the Polygons of Albrecht Dürer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Geometric Ornaments in Istanbul

►SKETCH 2 CONSTRUCTIONS OF REGULAR POLYGONS Regular polygons are the base elements for constructing the majority of Islamic geometric ornaments. Of course, in Islamic art there are geometric ornaments that may have different genesis, but those that can be created from regular polygons are the most frequently seen in Istanbul. We can also notice that many of the Islamic geometric ornaments can be recreated using rectangular grids like the ornament in our first example. Sometimes methods using rectangular grids are much simpler than those based or regular polygons. Therefore, we should not omit these methods. However, because methods for constructing geometric ornaments based on regular polygons are the most popular, we will spend relatively more time explor- ing them. Before, we start developing some concrete constructions it would be worthwhile to look into a few issues of a general nature. As we have no- ticed while developing construction of the ornament from the floor in the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, these constructions are not always simple, and in order to create them we need some knowledge of elementary geometry. On the other hand, computer programs for geometry or for computer graphics can give us a number of simpler ways to develop geometric fig- ures. Some of them may not require any knowledge of geometry. For ex- ample, we can create a regular polygon with any number of sides by rotat- ing a point around another point by using rotations 360/n degrees. This is a very simple task if we use a computer program and the only knowledge of geometry we need here is that the full angle is 360 degrees. -

Framing Cyclic Revolutionary Emergence of Opposing Symbols of Identity Eppur Si Muove: Biomimetic Embedding of N-Tuple Helices in Spherical Polyhedra - /

Alternative view of segmented documents via Kairos 23 October 2017 | Draft Framing Cyclic Revolutionary Emergence of Opposing Symbols of Identity Eppur si muove: Biomimetic embedding of N-tuple helices in spherical polyhedra - / - Introduction Symbolic stars vs Strategic pillars; Polyhedra vs Helices; Logic vs Comprehension? Dynamic bonding patterns in n-tuple helices engendering n-fold rotating symbols Embedding the triple helix in a spherical octahedron Embedding the quadruple helix in a spherical cube Embedding the quintuple helix in a spherical dodecahedron and a Pentagramma Mirificum Embedding six-fold, eight-fold and ten-fold helices in appropriately encircled polyhedra Embedding twelve-fold, eleven-fold, nine-fold and seven-fold helices in appropriately encircled polyhedra Neglected recognition of logical patterns -- especially of opposition Dynamic relationship between polyhedra engendered by circles -- variously implying forms of unity Symbol rotation as dynamic essential to engaging with value-inversion References Introduction The contrast to the geocentric model of the solar system was framed by the Italian mathematician, physicist and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). His much-cited phrase, " And yet it moves" (E pur si muove or Eppur si muove) was allegedly pronounced in 1633 when he was forced to recant his claims that the Earth moves around the immovable Sun rather than the converse -- known as the Galileo affair. Such a shift in perspective might usefully inspire the recognition that the stasis attributed so widely to logos and other much-valued cultural and heraldic symbols obscures the manner in which they imply a fundamental cognitive dynamic. Cultural symbols fundamental to the identity of a group might then be understood as variously moving and transforming in ways which currently elude comprehension. -

Formulas Involving Polygons - Lesson 7-3

you are here > Class Notes – Chapter 7 – Lesson 7-3 Formulas Involving Polygons - Lesson 7-3 Here’s today’s warmup…don’t forget to “phone home!” B Given: BD bisects ∠PBQ PD ⊥ PB QD ⊥ QB M Prove: BD is ⊥ bis. of PQ P Q D Statements Reasons Honors Geometry Notes Today, we started by learning how polygons are classified by their number of sides...you should already know a lot of these - just make sure to memorize the ones you don't know!! Sides Name 3 Triangle 4 Quadrilateral 5 Pentagon 6 Hexagon 7 Heptagon 8 Octagon 9 Nonagon 10 Decagon 11 Undecagon 12 Dodecagon 13 Tridecagon 14 Tetradecagon 15 Pentadecagon 16 Hexadecagon 17 Heptadecagon 18 Octadecagon 19 Enneadecagon 20 Icosagon n n-gon Baroody Page 2 of 6 Honors Geometry Notes Next, let’s look at the diagonals of polygons with different numbers of sides. By drawing as many diagonals as we could from one diagonal, you should be able to see a pattern...we can make n-2 triangles in a n-sided polygon. Given this information and the fact that the sum of the interior angles of a polygon is 180°, we can come up with a theorem that helps us to figure out the sum of the measures of the interior angles of any n-sided polygon! Baroody Page 3 of 6 Honors Geometry Notes Next, let’s look at exterior angles in a polygon. First, consider the exterior angles of a pentagon as shown below: Note that the sum of the exterior angles is 360°. -

Volume 2 Shape and Space

Volume 2 Shape and Space Colin Foster Introduction Teachers are busy people, so I’ll be brief. Let me tell you what this book isn’t. • It isn’t a book you have to make time to read; it’s a book that will save you time. Take it into the classroom and use ideas from it straight away. Anything requiring preparation or equipment (e.g., photocopies, scissors, an overhead projector, etc.) begins with the word “NEED” in bold followed by the details. • It isn’t a scheme of work, and it isn’t even arranged by age or pupil “level”. Many of the ideas can be used equally well with pupils at different ages and stages. Instead the items are simply arranged by topic. (There is, however, an index at the back linking the “key objectives” from the Key Stage 3 Framework to the sections in these three volumes.) The three volumes cover Number and Algebra (1), Shape and Space (2) and Probability, Statistics, Numeracy and ICT (3). • It isn’t a book of exercises or worksheets. Although you’re welcome to photocopy anything you wish, photocopying is expensive and very little here needs to be photocopied for pupils. Most of the material is intended to be presented by the teacher orally or on the board. Answers and comments are given on the right side of most of the pages or sometimes on separate pages as explained. This is a book to make notes in. Cross out anything you don’t like or would never use. Add in your own ideas or references to other resources. -

CONVERGENCE of the RATIO of PERIMETER of a REGULAR POLYGON to the LENGTH of ITS LONGEST DIAGONAL AS the NUMBER of SIDES of POLYGON APPROACHES to ∞ Pawan Kumar B.K

CONVERGENCE OF THE RATIO OF PERIMETER OF A REGULAR POLYGON TO THE LENGTH OF ITS LONGEST DIAGONAL AS THE NUMBER OF SIDES OF POLYGON APPROACHES TO ∞ Pawan Kumar B.K. Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding to: Pawan Kumar B.K., email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Regular polygons are planar geometric structures that are used to a great extent in mathematics, engineering and physics. For all size of a regular polygon, the ratio of perimeter to the longest diagonal length is always constant and converges to the value of 휋 as the number of sides of the polygon approaches to ∞. The purpose of this paper is to introduce Bishwakarma Ratio Formulas through mathematical explanations. The Bishwakarma Ratio Formulae calculate the ratio of perimeter of regular polygon to the longest diagonal length for all possible regular polygons. These ratios are called Bishwakarma Ratios- often denoted by short term BK ratios- as they have been obtained via Bishwakarma Ratio Formulae. The result has been shown to be valid by actually calculating the ratio for each polygon by using corresponding formula and geometrical reasoning. Computational calculations of the ratios have also been presented upto 30 and 50 significant figures to validate the convergence. Keywords: Regular Polygon, limit, 휋, convergence INTRODUCTION A regular polygon is a planar geometrical structure with equal sides and equal angles. For a 푛(푛−3) regular polygon of 푛 sides there are diagonals. Each angle of a regular polygon of n sides 2 푛−2 is given by ( ) 180° while the sum of interior angles is (푛 − 2)180°. The angle made at the 푛 center of any polygon by lines from any two consecutive vertices (center angle) of a polygon of 360° sides 푛 is given by . -

Geometry and Mensuration IV.7 11 Geometry and Mensuration

Geometry and Mensuration IV.7 11 Geometry and Mensuration The chapters on geometry and mensuration have their own The following is a comprehensive collection of formulae share of questions in the CAT and other MBA entrance ex- based on two-dimensional figures. The student is advised aminations. For doing well in questions based on this chapter, to remember the formulae in this chapter so that he is able the student should familiarise himself/herself with the to solve all the questions based on this chapter. basic formulae and visualisations of the various shapes of solids and two-dimensional figures based on this chapter. THEORY The following is a comprehensive collection of for- mulae based on two-dimensional and three-dimensional Basic Conversions figures: For the purpose of this chapter we have divided the A. 1 m = 100 cm = 1000 mm B. 1 m = 39.37 inches theory in two parts: 1 km = 1000 m 1 mile = 1760 yd ∑ Part I consists of geometry and mensuration of two- = 5/8 miles = 5280 ft dimensional figures 1 inch = 2.54 cm 1 nautical mile (knot) ∑ Part II consists of mensuration of three-dimensional = 6080 ft figures. C. 100 kg = 1 quintal D. 1 litre = 1000 cc 10 quintal = 1 tonne 1 acre = 100 sq m = 1000 kg PART I: GEOMETRY 1 kg = 2.2 pounds 1 hectare = 10000 sq m (approx.) INTRODUCTION TYPES OF ANGLES Geometry and Mensuration are important areas in the CAT examination. In the Online CAT, the Quantitative Aptitude Basic Definitions section has consisted of an average of 15–20% questions from these chapters. -

The Set of Vertices with Positive Curvature in a Planar Graph with Nonnegative Curvature

THE SET OF VERTICES WITH POSITIVE CURVATURE IN A PLANAR GRAPH WITH NONNEGATIVE CURVATURE BOBO HUA AND YANHUI SU Abstract. In this paper, we give the sharp upper bound for the number of vertices with positive curvature in a planar graph with nonnegative combinatorial curvature. Based on this, we show that the automorphism group of a planar|possibly infinite—graph with nonnegative combina- torial curvature and positive total curvature is a finite group, and give an upper bound estimate for the order of the group. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Preliminaries 7 3. Upper bound estimates for the size of TG 11 4. Constructions of large planar graphs with nonnegative curvature 24 5. Automorphism groups of planar graphs with nonnegative curvature 27 References 31 Mathematics Subject Classification 2010: 05C10, 31C05. 1. Introduction The combinatorial curvature for a planar graph, embedded in the sphere or the plane, was introduced by [Nev70, Sto76, Gro87, Ish90]: Given a pla- arXiv:1801.02968v2 [math.DG] 22 Nov 2018 nar graph, one may canonically endow the ambient space with a piecewise flat metric, i.e. replacing faces by regular polygons and gluing them together along common edges. The combinatorial curvature of a planar graph is de- fined via the generalized Gaussian curvature of the metric surface. Many in- teresting geometric and combinatorial results have been obtained since then, see e.g. [Z97,_ Woe98, Hig01, BP01, HJL02, LPZ02, HS03, SY04, RBK05, BP06, DM07, CC08, Zha08, Che09, Kel10, KP11, Kel11, Oh17, Ghi17]. Let (V; E) be a (possibly infinite) locally finite, undirected simple graph with the set of vertices V and the set of edges E: It is called planar if it is topologically embedded into the sphere or the plane. -

Workbook Spring Year 9

Workbook Spring Year 9 2 Copyright © Mathematics Mastery 2018-19 Contents Unit 8: Construction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 8.1: Constructing triangles (review of Year 8)........................................................................................... 4 8.2: Constructing perpendicular bisectors and angle bisectors .......................................................... 7 8.3: Mixed questions (constructing triangles, perpendicular bisectors and angle bisectors) .................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 8.4: Mixed problems ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Unit 9: Congruence .................................................................................................................................................. 16 9.1: Congruent figures ....................................................................................................................................... 16 9.2: Congruence conditions for triangles ................................................................................................... 20 9.3: Mixed problems .......................................................................................................................................... -

US 2007/0203566A1 Arbefeuille Et Al

US 20070203566A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0203566A1 Arbefeuille et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 30, 2007 (54) NON-CIRCULAR STENT (60) Provisional application No. 60/499,652, filed on Sep. 3, 2003. Provisional application No. 60/500,155, filed on Sep. 4, 2003. (75) Inventors: Samuel Arbefeuille, Hollywood, FL (US); Humberto Berra, Cooper City, Publication Classification FL (US) (51) Int. Cl. Correspondence Address: A6IF 2/86 (2006.01) MAYBACK & HOFFMAN, P.A. (52) U.S. Cl. .......................................... 623/1.13; 623/1.15 5722 S. FLAMINGO ROAD #232 (57) ABSTRACT FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33330 (US) A vascular repair device includes a tubular graft body having (73) Assignee: Bolton Medical, Inc., Sunrise, FL a central longitudinal axis and a structural framework having at least one stent connected to the graft body in a partially (21) Appl. No.: 11/699,700 compressed state, the stent having Substantially linear Struts and apices between adjacent pairs of the Struts, each of the (22) Filed: Jan. 30, 2007 apices being in the same plane as the adjacent pairs of the struts. Also provided is a vascular repair device where the Related U.S. Application Data stent defines a cross plane orthogonal to the longitudinal axis and has a cross profile having a polygonal shape parallel to (62) Division of application No. 10/784,462, filed on Feb. the cross-sectional plane and viewed along said longitudinal 23, 2004. aX1S. Patent Application Publication Aug. 30, 2007 Sheet 1 of 21 US 2007/0203566A1 g Patent Application Publication Aug. 30, 2007 Sheet 2 of 21 US 2007/020356.6 A1 N g LL CO CN S O N CN N s O O CD S - Patent Application Publication Aug. -

Anglická Matematická Terminologie/ English Mathematical Terminology

UNIVERZITA OBRANY FAKULTA VOJENSKÝCH TECHNOLOGIÍ BRNO 2011 KATEDRA MATEMATIKY A FYZIKY Jaromír Kuben Anglická matematická terminologie/ English mathematical terminology Vytvořeno v rámci projektu Operačního programu Vzdělávání pro konkurenceschopnost CZ.1.07/2.2.00/07.0256 Inovace studijního programu Vojenské technologie/ Rozšiřování výuky odborných kurzů v angličtině Tento projekt je spolufinancován Evropským sociálním fondem a státním rozpočtem České republiky INVESTICE DO ROZVOJE VZDĚLÁVÁNÍ Jaromír Kuben Anglická matematická terminologie/English mathematical terminology c Jaromír Kuben, 2011 Předmluva/Preface Tento materiál byl připraven jako součást projektu Operačního programu Vzdělávání pro konkurenceschopnost, majícího název Inovace studijního programu Vojenské technologie, dílčí aktivita Rozšiřování výuky odborných kurzů v angličtině. Projekt je spolufinancován Evropským sociálním fondem a státním rozpočtem ČR. Cílem tohoto textu je usnadnit studentům, kteří studovali na základní a střední škole matematiku v češtině, přechod na výuku vysokoškolské matematiky v angličtině. U těchto studentů se sice předpokládá znalost středoškolské matematiky (a matematiky ze základní školy), ale pouze v češtině. Pokud jde o anglickou matematickou terminologii, jsou jejich znalosti obvykle zanedbatelné. Text je rozdělen do dvou částí. První, označená jako Středoškolská látka a obecná terminologie, zahrnuje tematicky členěnou slovní zásobu z matematických partií probíraných na základní a střední škole, doplněnou o některé užitečné a potřebné výrazy a obraty, které se v matematických textech často vyskytují. S touto částí by se posluchači měli průběžně samostatně seznamovat, aby byli schopni rozumět běžné matematické terminologii, se kterou se setkávají prakticky ve všech tématech vysokoškolské matematiky. Ideální by byl úvodní „jazykový“ kurz, v němž by se podstatnou část této slovní zásoby naučili. Protože to není možné, měli by si samostatně vybírat jednotlivá témata podle toho, co nejvíce postrádají, a postupně tuto slovní zásobu doplňovat. -

Summary of Dynamics of the Regular Tridecagon: N = 13 the Following Arxiv Articles Have Background Information About the Dynamics of Regular N- Gons

DynamicsOfPolygons.org Summary of dynamics of the regular tridecagon: N = 13 The following arXiv articles have background information about the dynamics of regular N- gons. [H5] has recently been updated and it is recommended. We will summarize some of the content here. H2] Hughes G.H., Outer billiards, digital filters and kicked Hamiltonians, arXiv:1206.5223 [H3] Hughes G.H., Outer billiards on Regular Polygons, arXiv:1311.6763 [H4] Hughes G.H., First Families of Regular Polygons arXiv: 1503.05536 H[5] Hughes G.H. First Families of Regular Polygons and their Mutations arXiv: 1612.09295 The algebraic complexity of any prime N-gon is (N-1)/2 so N = 13 (and the matching N = 26) are ‘order’ 6 along with N = 21, 36 and 42. Very little is known about the dynamics of these polygons – but in general polygons with the same algebraic complexity appear to have similar dynamics. The First Family is shown below. The generation scaling for N odd or twice-odd is relative to DS[2] – which plays the role of the second generation D tile – so it is often called D[1]. The matching scaled copy of N = 13 is called M[1]. In both cases the scale is GenScale[13]: ππ GenScale[13] = scale[6] = Tan[ ] Tan []≈ 0.02992783094972740245925. 26 13 When N is odd it is common to embed N inside 2N - as shown below. This has no effect on the cyclotomic field and the scaling is compatible, so algebraically and geometrically they are equivalent. Since the generation scaling is based on D – this embedding is sometimes unavoidable. -

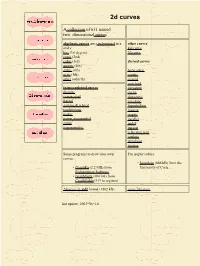

2Dcurves in .Pdf Format (1882 Kb) Curve Literature Last Update: 2003−06−14 Higher Last Updated: Lennard−Jones 2002−03−25 Potential

2d curves A collection of 631 named two−dimensional curves algebraic curves are a polynomial in x other curves and y kid curve line (1st degree) 3d curve conic (2nd) cubic (3rd) derived curves quartic (4th) sextic (6th) barycentric octic (8th) caustic other (otherth) cissoid conchoid transcendental curves curvature discrete cyclic exponential derivative fractal envelope gamma & related hyperbolism isochronous inverse power isoptic power exponential parallel spiral pedal trigonometric pursuit reflecting wall roulette strophoid tractrix Some programs to draw your own For isoptic cubics: curves: • Isoptikon (866 kB) from the • GraphEq (2.2 MB) from University of Crete Pedagoguery Software • GraphSight (696 kB) from Cradlefields ($19 to register) 2dcurves in .pdf format (1882 kB) curve literature last update: 2003−06−14 higher last updated: Lennard−Jones 2002−03−25 potential Atoms of an inert gas are in equilibrium with each other by means of an attracting van der Waals force and a repelling forces as result of overlapping electron orbits. These two forces together give the so−called Lennard−Jones potential, which is in fact a curve of thirteenth degree. backgrounds main last updated: 2002−11−16 history I collected curves when I was a young boy. Then, the papers rested in a box for decades. But when I found them, I picked the collection up again, some years spending much work on it, some years less. questions I have been thinking a long time about two questions: 1. what is the unity of curve? Stated differently as: when is a curve different from another one? 2. which equation belongs to a curve? 1.