When Evil Begets Evil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conscience and Peace Tax International

Conscience and Peace Tax International Internacional de Conciencia e Impuestos para la Paz NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the UN International non-profit organization (Belgium 15.075/96) www.cpti.ws Bruineveld 11 • B-3010 Leuven • Belgium • Ph.: +32.16.254011 • e- : [email protected] Belgian account: 000-1709814-92 • IBAN: BE12 0001 7098 1492 • BIC: BPOTBEB1 UPR SUBMISSION CANADA FEBRUARY 2009 Executive summary: CPTI (Conscience and Peace Tax International) is concerned at the actual and threatened deportations from Canada to the United States of America of conscientious objectors to military service. 1. It is estimated that some 200 members of the armed forces of the United States of America who have developed a conscientious objection to military service are currently living in Canada, where they fled to avoid posting to active service in which they would be required to act contrary to their consciences. 2. The individual cases differ in their history or motivation. Some of those concerned had applied unsuccessfully for release on the grounds that they had developed a conscientious objection; many had been unaware of the possibility of making such an objection. Most of the cases are linked to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent military occupation of that country. Some objectors, including reservists mobilised for posting, refused deployment to Iraq on the grounds that this military action did not have lawful approval of the international community. Others developed their conscientious objections only after deployment to Iraq - in some cases these objections related to armed service in general on the basis of seeing what the results were in practice; in other cases the objections were specific to the operations in which they had been involved and concerned the belief that war crimes were being committed and that service in that campaign carried a real risk of being faced with orders to carry out which might amount to the commission of war crimes. -

Law and Resistance in American Military Films

KHODAY ARTICLE (Do Not Delete) 4/15/2018 3:08 PM VALORIZING DISOBEDIENCE WITHIN THE RANKS: LAW AND RESISTANCE IN AMERICAN MILITARY FILMS BY AMAR KHODAY* “Guys if you think I’m lying, drop the bomb. If you think I’m crazy, drop the bomb. But don’t drop the bomb just because you’re following orders.”1 – Colonel Sam Daniels in Outbreak “The obedience of a soldier is not the obedience of an automaton. A soldier is a reasoning agent. He does not respond, and is not expected to respond, like a piece of machinery.”2 – The Einsatzgruppen Case INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 370 I.FILMS, POPULAR CULTURE AND THE NORMATIVE UNIVERSE.......... 379 II.OBEDIENCE AND DISOBEDIENCE IN MILITARY FILMS .................... 382 III.FILM PARALLELING LAW ............................................................. 388 IV.DISOBEDIENCE, INDIVIDUAL AGENCY AND LEGAL SUBJECTIVITY 391 V.RESISTANCE AND THE SAVING OF LIVES ....................................... 396 VI.EXPOSING CRIMINALITY AND COVER-UPS ................................... 408 VII.RESISTERS AS EMBODIMENTS OF INTELLIGENCE, LEADERSHIP & Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Article in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete citation, and this copyright notice and grant of permission be included in all copies. *Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba; J.D. (New England School of Law); LL.M. & D.C.L. (McGill University). The author would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in reviewing, providing feedback and/or making suggestions: Drs. Karen Crawley, Richard Jochelson, Jennifer Schulz; Assistant Professor David Ireland; and Jonathan Avey, James Gacek, Paul R.J. -

The Good Soldier: Former US Serviceman Joshua Key, Refuses to Fight in Iraq

The Good Soldier: Former US Serviceman Joshua Key, Refuses to Fight in Iraq. Living in Limbo. By Michael Welch Region: Canada, Middle East & North Global Research, April 03, 2015 Africa, USA Theme: GLOBAL RESEARCH NEWS HOUR “I will never apologize for deserting the American army. I deserted an injustice and leaving was the only right thing to do. I owe one apology and one apology only, and that is to the people of Iraq.” -Joshua Key in The Deserter’s Tale LISTEN TO THE SHOW Length (59:19) Click to download the audio (MP3 format) Joshua Key is one of dozens of US GIs who sought refuge in Canada rather than be forced to serve in a war they considered legally and morally wrong. He served from April to November of 2003, the first year of the war. He then went AWOL during a visit to the United States. By March of 2005 he had made it up to Canada and sought refugee status. Ten years ago, Canada had earned respect around the world for refusing to officially join then President Bush’s ‘Coalition of the Willing.’ Times have changed since those early years. The Canadian government under Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper is arguably the most bellicose Western leader with regard to military offensives, supposedly against ISIS/ISIL in Iraq. This same government is now determined to return all military deserters back to the US where they face lengthy prison sentences, especially if they have been outspoken against the war. Joshua Key was the very first US GI to write a memoir of his time in Iraq, let alone a critical account. -

Struggle and Survival of American Veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom

Struggle and Survival of American Veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Koopman, David Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 15:16:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/628125 1 STRUGGLE AND SURVIVAL OF AMERICAN VETERANS OF OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM by David Koopman ____________________________ Copyright © David Koopman 2018 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MIDDLE EASTERN AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 2 3 Contents 1. Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 2. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………...5 3. Framework………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 4. Recruitment and training……………………………………………………………………………………12 5. Military towns and environment…………………………………………………………………………18 6. OIF: The war without a mission…………………………………………………………………………..23 7. FOB culture………………………………………………………………………………………………………..31 8. Outside the wire…………………………………………………………………………………………………38 9. Coming home……………………………………………………………………………………………………..47 10. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………54 11. Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………………………….61 -

First Draft IARLJ Conference Slovenia

Draft Dodger/ Deserter or Dissenter? Conscientious objection as grounds for refugee status Final Draft Human Rights Nexus Working Group IARLJ conference Slovenia 2011 Prepared by Penelope Mathew Freilich Foundation professor, The Australian National University This working group paper looks at the state of the law concerning conscientious objectors in a number of jurisdictions: Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The author would like to thank all judges who provided case-law and comments, along with Ms Trina Ng who collected more case law and secondary literature and the colleagues working on the IARLJ working group papers. In general, the law may be considered up to date as of December 2010, although a 2011 decision of the European Court of Human Rights and a 2011 German decision have been included because of their importance. The paper considers the following questions: 1. What have international authorities said regarding conscientious objection and human rights and what questions arise for consideration by refugee status decision-makers? 2. Are conscientious objectors to military service presently granted refugee status as a general rule in the jurisdictions surveyed, and why/not? 3. Do the jurisdictions surveyed recognize a ‘partial’ conscientious objector status when a particular war involves violations of international law? 4. Does the national case law require the illegality to stem from the jus in bello or international humanitarian law, or may it also stem from the jus ad bellum, particularly the United Nations Charter’s prohibition on unilateral uses of force in Article 2(4)? 5. Where a partial exception is recognized on the basis of international humanitarian law violations, how serious and widespread must they be, and is risk of participation or mere association through military service required for refugee status to be granted? 6. -

Bodies of Evidence: New Documentaries on Iraq War Veterans

Bodies of Evidence New Documentaries on Iraq War Veterans by Susan L. Carruthers e's a villain or a hero; spat upon or Retrieving these women from the Penta- and Sommers such wrangling is rather spitting. He's an accessory to war gon's memory hole is central to McLagan beside the point. Since women are already in H crimes; an antiwar crusader. He's a and Sommers's project. Male Army officers combat, the immediate issues are much tic-ridden time bomb; a paraplegic demon explain how they initially looked to female more practical ones about inadequate prior lover. He's a Vietnam veteran—of Holly- soldiers for a less "culturally insensitive" training and insufficient aftercare from a wood's imagination. And now he's joined by way to body search Iraqi women and to soft- Veterans Administration caught off guard a new generation of homecoming soldiers en the affront of house-to-house raids. In its by the appearance of an unexpected species back from Iraq and burdened with many of imagined form, women's service in these of claimant. As such, the film is less an argu- the same afflictions. Skirting the war zone in capacities would be "a neat thing to do"—a ment about women in combat than an favor of domestic drama, films like Irwin badge of distinction that merited a distinc- affecting portrait of women after combat. Winkler's Home of the Brave, Paul Haggis's tive mantle. Having "joked around" with the More meditative than didactic, it focuses on In the Valley ofElah, and Kimberley Peirce's idea of calling them "shield maidens" or the exhausting battles of daily life with the Stop-Loss have pitted dam- traumatized veteran as both aged returnees against an recipient and provider of indifferent citizenry that Documentary filmmakers gauge the human care, mothering young chil- doesn't know how to handle dren and ailing parents them and a rapacious mili- factor as emotionally and physically shattered alike. -

Seeking Status, Forging Refuge: U.S. War Resister Migrations to Canada Alison Mountz

Document generated on 10/02/2021 5:24 p.m. Refuge Canada's Journal on Refugees Revue canadienne sur les réfugiés Seeking Status, Forging Refuge: U.S. War Resister Migrations to Canada Alison Mountz Symposium: Beyond the Global Compacts Article abstract Volume 36, Number 1, 2020 Often people migrate through interstitial zones and categories between state territories, policies, or designations like “immigrant” or “refugee.” Where there URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1069756ar is no formal protection or legal status, people seek, forge, and find safe haven DOI: https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.40648 in other ways, by other means, and by necessity. In this article, I argue that U.S. war resisters to Canada forged safe haven through broadly based social See table of contents movements. I develop this argument through examination of U.S. war-resister histories, focusing on two generations: U.S. citizens who came during the U.S.-led wars in Vietnam and, more recently, Afghanistan and Iraq. Resisters and activists forged refuge through alternative paths to protection, including Publisher(s) the creation of shelter, the pursuit of time-space trajectories that carried Centre for Refugee Studies, York University people away from war and militarism, the formation of social movements across the Canada-U.S. border, and legal challenges to state policies and practices. ISSN 0229-5113 (print) 1920-7336 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mountz, A. (2020). Seeking Status, Forging Refuge: U.S. War Resister Migrations to Canada. Refuge, 36(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.40648 Copyright (c), 2020 Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees This document is protected by copyright law. -

God Is in Control’

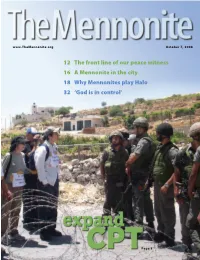

1119finalwads.qxd 10/1/2008 7:10 AM Page 1 www.TheMennonite.org October 7, 2008 12 The front line of our peace witness 16 A Mennonite in the city 18 Why Mennonites play Halo 32 ‘God is in control’ Page 8 1119finalwads.qxd 10/1/2008 7:10 AM Page 2 MENNONITE CHURCH USA Seeing as God sees ome of us are tired of all the vision talk in our tions and hence in our churchwide witness. congregations or the larger church. Others Most of the time we don’t get to see brand new S are interested but speak about vision in things or dramatic new ministries. Transformation hushed tones, as though it’s a special gift reserved happens when we are able to see old things in new only for leaders and assorted charismatics. The ways—full of new possibilities. Vision is transform- truth is most of us take vision for granted. Vision ing when we adopt a new view of ourselves. is simply how we see things. We don’t realize the Things change for the better when we can see that value of vision until we can’t see things any more. annoying person sitting down the pew or our For the Christian, vision is “seeing things as neighbor in a new way. God sees them.” I remember the moment I real- When I was a young preacher more than 30 ized I needed glasses. I was 16 and watching a bas- years ago, our preschool daughter always sat in ketball game. Fooling around, I asked a friend if I the back bench with her mother. -

March 8 FIDEL’S 12 Noon Rally Message 10 Union Square 14Th St

Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org FEB. 28, 2008 VOL. 50, NO. 8 50¢ More fallout from capitalist downturn • El presupuesto de Bush • Venezuela contra Exxon 12 Towns, cities face MICHIGAN Fighting bank foreclosures 3 drastic service cuts By Jaimeson Champion revenue and municipal bond issuances. Tax revenue is declin- ing as plummeting property values mean less money in prop- YOUTH JOBS Crises of overproduction have occurred with destructive regu- erty taxes and slowing economic activity results in less sales tax Implode with service larity throughout the history of capitalism. During these cyclical revenue. At the same time, the market for municipal bonds is slump 3 crises, the ruling class systematically tries to force the working rapidly deteriorating. class to bear the brunt of the fallout. In the current crisis, the systematic attacks on the working Now insurers are defaulting MUMIA RULING class and oppressed are painfully clear. Millions of families are Historically, investors have been more than willing to buy being forced from their homes by foreclosures. Massive layoffs municipal bonds issued by U.S. cities, states and towns because 4 Leaves one more appeal have begun across all sectors of the economy. most of them have been insured against default by financial It is the workers who are being forced to pay the toll for a cri- institutions known as monoline bond insurers. sis that the bankers and bosses caused. This crisis has brought But currently, these monoline bond insurers, such as MBIA RESISTERS to the forefront class antagonisms that the superrich have long and Ambac Financial Group, have balance sheets soaked in red TO WAR sought to obscure. -

Executive Report: January 21, 2015 – February 27, 2015

1 Executive Report: January 21, 2015 – February 27, 2015 THE U W S A Executive Report Executive Report 0R30-515 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 2E9 Phone: (204) 786-9792 Fax: (204) 783-7080 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: theuwsa.ca 2 Executive Report: January 21, 2015 – February 27, 2015 UWSA Executives: President Rorie Mcleod Arnould, Vice-President Students Services Allison Reimer Vice-President Internal Lee Chitty, Vice-President Advocate Peyton Veitch Executive Summary This report covers the period of January 21, 2015 to February 27, 2015 and is the ninth submitted to the 2014-2015 UWSA Board of Directors. Contained in the report are the summary of meetings both internal and external, list of media appearances, reports on solidarity and advocacy work, and services updates. We enter into the final weeks of our mandate with an awareness of our successes and failures. As outlined in this report and others, we have made several steps towards the goals set out by our members. We should be proud of what has been accomplished by our members, and appreciate the positive energy invested in organizing towards our common goals. Equally, we must also hold our shortcomings in mind as we prepare for the coming year. To that end, the final versions of this report will contain “Failure Reports”, written by members of our union. These reports will outline instances where we have failed, created by our shortcomings in any number of areas, and the necessary steps we must all take to improve. The intention of these reports is not to demean ourselves, or focus on the negative: instead, they are opportunities for radical transparency and honestly with our membership in order to ensure consistent progress. -

American War Resister Cases in the Canadian Federal Court 81

American War Resister Cases in the Canadian Federal Court 233 American War Resister Cases in the Canadian Federal Court Edward C. Corrigan, B.A., M.A., LL.B.* There has been mixed treatment at the Canadian Federal Court of U.S. deserters who have claimed refugee status in Canada on the basis of refusal to serve in the U.S. military. To quote one article: In their battle to secure asylum in Canada, U.S. military deserters are being sorted into winning and losing camps by the Federal Court, which some law- yers contend has been inconsistent and confusing in its treatment of war re- sisters. In six court decisions in the last two years, there have been four losers and two winners among the first batch of former soldiers to challenge their defeats at the Immigration and Refugee Board. “We’ve got a divided court,” said Toronto lawyer Geraldine Sadoway, whose client, Justin Colby, recently lost his refugee bid, after fleeing to Canada two years ago following a one-year stint as a medic in Iraq. Ms. Sadoway says she cannot figure out why the Federal Court rejected Mr. Colby’s claim on June 26, only one week before it handed the first ever victory to deserter Joshua Key, who also served in Iraq.1 To date there have been at least ten cases considered by the Canadian Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal on the U.S. war resister issue. In seven of those cases the decision went against the Americans who claimed refugee status on the basis of refusal to serve in the U.S. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2007

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2007 Geschichte: Einführungen........................................................................................................................................2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie ..........................................................................................................2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein) ........4 Historische Hilfswissenschaften ..............................................................................................................................7 Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie.................................................................................8 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege......................................10 Alte Geschichte......................................................................................................................................................18 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit ...............................................................................................20 Deutsche Geschichte..............................................................................................................................................22 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte .....................................................................................................30 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs,