A Critical Analysis of August Burns Red Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Pressemitteilung Zu Cancer Bats

Pressemitteilung zu Cancer Bats Die Hardcore-Metal-Punks Cancer Bats präsentieren ihr sechstes Album „The Spark That Moves“ bei einem krachenden Konzert im Headcrash am 23.03. live Hamburg, November 2018 – Mit 13 Jahren Bandgeschichte hinter sich und fünf gefeierten Studioalben, drei Juno-Award-Nominierungen und unzähligen Touren rund um den Globus ist aus den kanadischen Hardcore-Metal-Punks Cancer Bats eine wohlbekannte Macht in der Welt der Heavy Music geworden. 2018 startet die Band das neuste Kapitel ihrer Karriere: Auf eigene Faust veröffentlichen sie ihr sechstes Studioalbum „The Spark That Moves“ über ihr eigenes Label Bat Skull Records. Nun wollen sie Alben nicht nur zu ihren eigenen Bedingungen aufnehmen, sondern auch auf die traditionellen Lead-Ups und Teaser-Singles verzichten – ohne jede Vorwarnung erscheint „The Spark That Moves“ in seiner Gänze am 20. April 2018 mit Vinyl und CDs. Wie dieses Album live klingt, ist am 23.03. im HeadCrash zu erleben. „Wir waren es einfach leid, zu warten“, so Frontmann Liam Joseph Cormier. „Wir haben 2017 vollständig damit verbracht, hart an diesem Album zu arbeiten, währenddessen wir Shows gespielt und mit unseren Fans geredet haben, die uns permanent gefragt haben: Pressekontakt: Erik Sabas +49 40 4133018-40 [email protected] river_concerts www.riverconcerts.de River Concerts ‚Wann kriegen wir neue Musik zu hören?‘ Warum also irgendjemanden noch länger warten lassen? Lass uns einfach das ganze Album auf einmal herausbringen“, schwärmt Cormier. „Ich weiß, dass ich als Fan einfach alles sofort hören will. Lass mich das Album jetzt gleich kaufen! Wir haben uns gefragt, wieso wir unsere Musik nicht einfach so veröffentlichen, wie wir es wollen.“ Für ihr sechstes Album ging die Band nicht nur einen neuen Weg, um ihre Musik zu veröffentlichen, sondern musste lernen, auch auf völlig neue Weise ihre Songs zu schreiben, da Schlagzeuger Mike Peters nun in Winnipeg wohnt. -

Freezine Pdf0040.Pdf

09/2012 Mighty v osmém vydání zdá se teď být jen zdání jako deštík, co nás zkrápěl každý den, ať kdokoli pěl. Mírný vánek na Čápáku vál kdekdo z nás se hurikánu bál bylo vše však velmi krásné, Mysli naše byly jasné. Ačkoliv jsem předala před časem vedení To však spíše trochu kecám, Mighty Freezinu Anselmovi, pořád na Mighty nikdo není sám, samozřejmě cítím vůči tomuto výjimečnému přítele či přítelkyni, časopisu náklonnost, něžnost a jsem na něj ať morgana či jackyni, tak trochu pyšná. Anselmo s Marcelem si do- každý najde, co hledá, cela dobře vedou, na to, že jsou to jen muži. (někdy až do oběda). Dnes, když můžu oslovit statisíce čtenářů Každopádně štěstí tryská v úvodníku, nevím, jak nejlépe vystihnout ze Čápova letiska. vše, čím mé srdce překypuje. Rozhodla jsem se tedy poctít vás (nás všechny) uměním Bylo to zas velmi hutné nejvyšším: poezií. Mohla bych tuto skvělou Nyní je to trochu smutné, báseň zařadit do své sbírky, která bude brzy ale jelikož to letí, vydána (a bude to bestseller, takže sledujte brzy bude, milé děti, svá oblíbená knihkupectví a včas si toto Mighty číslo nula devět - výjimečné dílo obstarejte). Ale raději ji stačí přečíst několik vět věnuji vám, milí obyčejní mighty lidé. Mám každý měsíc. Tenhle plátek vás (docela) ráda. Vaše Mq pak ohlásí ten velký svátek! DYING Ladrogang presents FETUS 23.9. Klub 007 Strahov THE KLINGONZ (uk/irl), ROCKET DOGZ (cz) Psychobilly rock´n´roll invasion from outter space! 30.9. Klub 007 Strahov Revocation 02.10.2012 Cerebral Bore WARHEAD (jap), FUK (uk, ex-Chaos UK), PORKERIA (usa) ostravaostrava - bbarakBARRÁK This is kick ass punk! Japan vs UK vs Texas! 4.10. -

Blessthefall What Left of Me Mp3 Download

Blessthefall what left of me mp3 download Blessthefall What's Left Of Me. Now Playing. What S Left Of Me. Artist: Blessthefall. MB. Advertisement. Blessthefall What's Left Of Me · Jessica Simpson Nick Lachey A Whole New World · Donell Jones U Know What's Up Ft Left Eye · Left Right Left Charlie Puth. BLESSTHEFALL WHAT LEFT OF ME MP3 Download ( MB), Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 BLESSTHEFALL WHAT LEFT OF ME ( play download. Whats Left of Me ; Nick Lachey (Lyrics) Duration: - Source: youtube - FileType: mp3 - Bitrate: Kbps. play download. Blessthefall - 'What's. Buy What's Left Of Me: Read Digital Music Reviews - Artist: Blessthefall. test. ru MB. Advertisement. BLESSTHEFALL WHAT LEFT OF ME MP3 Download (MB), Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3. Whats Left of Me ; Nick Lachey (Lyrics) Duration: Source: youtube - FileType: mp3 - Bitrate: Kbps. play download. Blessthefall - 'What's. Blessthefall Whats Left. Nick Lachey Whats Left Of Me. MB • plays S Left Of Me. Blessthefall • MB • plays 13leave What S Left Of Me Rock A Teens MB • blessthefall MP3 Download. Download blessthefall MP3 with MP3Juices. Blessthefall - "What's Left of Me" Official Music Video · Download MP3. Artist: blessthefall, Song: The Sound Of Starting Over, Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, File type: mp3 . Blessthefall What's left of me Official music video for "What's Left of Me" by blessthefall. Witness is Download it on iTunes: http. "" and "Whalts Left of Me" by Blessthefall ____(Read Full Description) Please comment and let me know. Provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group North America What's Left Of Me · Blessthefall Witness. -

ANTI-FLAG & SILVERSTEIN 21. Oktober 2018 Stuttgart-Wangen

ANTI-FLAG & SILVERSTEIN 21. Oktober 2018 Stuttgart-Wangen LKA/Longhorn Gäste: Cancer Bats, Worriers Vier Bands an einem Abend? Das gibt es im Oktober, wenn ANTI-FLAG und SILVERSTEIN zusammen mit zwei weiteren special guests für sieben Konzerte nach Deutschland kommen. Im vergangen Jahr veröffentlichte das Pittsburgher Quartett ANTI-FLAG mit "American Fall" ihr zehntes und bis dato reifstes Studioalbum via Spinefarm Records. Anlass für die neue Platte war die veränderte politische Weltlage aufgrund der kontroversen Wahl des US-Präsidenten. Seit mehr als 20 Jahren setzen ANTI- FLAG mit ihren Alben politische Statements, daher ist es nicht verwunderlich, dass das auch bei "American Fall" der Fall ist. Obwohl die Band sich weiterhin treu bleiben wollte, suchte sie sich ebenso eine neue Herausforderung in der Arbeit an ihrem zehnten Werk. Der altbekannte Sound der Band entwickelte sich hin zu langsamen Grooves, kompakteren Songwriting, satteren Gitarren und größeren Melodien. Kurz: der perfekte musikalische Gegensatz zum heiklen Thema des Albums. "Wir leben in düsteren und polarisierenden Zeiten. Wir wollten unsere Message also nicht auf überhebliche oder beklemmende Art und Weise unter die Hörer bringen", berichtet Justin Sane. "Mit ein bisschen mehr Melodie lässt sich die Pille besser schlucken. So ist es wirkungsvoller und einfacher." Die zweite Größe des Abends ist SILVERSTEIN. Die Post-Hardcore Band wurde im Jahr 2000 in Burlington (Ontario, Kanada), gegründet. Seit ihrer Gründung spielte die Band bereits unter anderem als Vorband von Simple Plan und Billy Talent. Im Juli 2017 veröffentlichten SILVERSTEIN ihr neuntes Studioalbum "Dead Reflection", welches eine "Was-wäre-wenn" Version des Lebens von Shane Told (Sänger) erzählt. -

Vans Warped Tour Deck

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH WIFI HOTSPOT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITY BRANDED WIFI LOUNGE “Verizon Zone” Pepsi Zone” etc. THE WARPED AUDIENCE///////////////////////////// The Warped fan is a highly sociable, tech savvy and influential young adult. Attendees are utilizing social networking to communicate their concert experiences to friends across the globe. The average attendee has been to Ages 15 ‐25 make up 91% Diversity Warped Tour 3 years and nearly of the VWT audience 90% of festival goers visit the sponsor and non-‐profit village 62% 22% ////////////////////////////////////////// 39% 52% 98% of fans take home everything // WHITE/ // LATINO they get from the tour CAUCASIAN // 15-17 // 18-25 ////////////////////////////////////////// 10% 6% Overall, 82.6% of fans are more Average Age: 17.9 years old likely to purchase or try a sponsor’s product due to their association // AFRICAN- with Warped Tour, indicating // ASIAN AMERICAN positive brand awareness. 47.9% 52.1% // MALE // FEMALE 2015 ROUTING///////////////////////////////////////// 6/19 // Pomona, CA 7/7 //Charlotte, NC 7/24 // Detroit, MI 6/20 // San Francisco, CA 7/8 // Virginia Beach, VA 7/25 // Chicago, IL 6/21 // Ventura, CA 7/9 // Pittsburgh, PA 7/26 // Shakopee, MN 6/23 // Mesa, AZ 7/10 // Camden, NJ 7/27 // Maryland Heights, MO 6/24 // Albuquerque, NM 7/11 // Wantagh, NY 7/28 // Milwaukee, WI 6/25 // Oklahoma City, OK 7/12 // Hartford, CT 7/29 // Noblesville, IN 6/26 // Houston, TX 7/14 // Mansfield, MA 7/30 // Bonners Spring, KS 6/27 // Dallas, TX 7/15 // Darien Center, NY 8/1 // Salt Lake City, UT 6/28 // San Antonio, TX 7/16 // Cincinnati, OH 8/2 // Denver, CO 7/1 // Nashville, TN 7/17 // Toronto, ON 8/5 // San Diego, CA 7/2 // Atlanta, GA 7/18 // Columbia, MD 8/7 // Portland, OR 7/3 // St. -

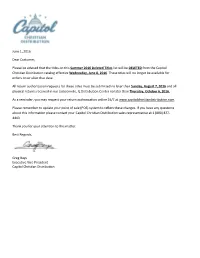

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Hot Topic Presents the 2011 Take Action Tour

For Immediate Release February 14, 2011 Hot Topic presents the 2011 Take Action Tour Celebrating Its 10th Anniversary of Raising Funds and Awareness for Non-Profit Organizations Line-up Announced: Co-Headliners Silverstein and Bayside With Polar Bear Club, The Swellers and Texas in July Proceeds of Tour to Benefit Sex, Etc. for Teen Sexuality Education Pre-sale tickets go on sale today at: http://tixx1.artistarena.com/takeactiontour February 14, 2011 – Celebrating its tenth anniversary of raising funds and awareness to assorted non-profit organizations, Sub City (Hopeless Records‟ non-profit organization which has raised more than two million dollars for charity), is pleased to announce the 2011 edition of Take Action Tour. This year‟s much-lauded beneficiary is SEX, ETC., the Teen-to-Teen Sexuality Education Project of Answer, a national organization dedicated to providing and promoting comprehensive sexuality education to young people and the adults who teach them. “Sex is a hot topic amongst Take Action bands and fans but rarely communicated in a honest and accurate way,” says Louis Posen, Hopeless Records president. “Either don't do it or do it right!" Presented by Hot Topic, the tour will feature celebrated indie rock headliners SILVERSTEIN and BAYSIDE, along with POLAR BEAR CLUB, THE SWELLERS and TEXAS IN JULY. Kicking off at Boston‟s Paradise Rock Club on April 22nd, the annual nationwide charity tour will circle the US, presenting the best bands in music today while raising funds and awareness for Sex, Etc. and the concept that we can all play a part in making a positive impact in the world. -

Christian Rock Concerts As a Meeting Between Religion and Popular Culture

ANDREAS HAGER Christian Rock Concerts as a Meeting between Religion and Popular Culture Introduction Different forms of artistic expression play a vital role in religious practices of the most diverse traditions. One very important such expression is music. This paper deals with a contemporary form of religious music, Christian rock. Rock or popular music has been used within Christianity as a means for evangelization and worship since the end of the 1960s.1 The genre of "contemporary Christian music", or Christian rock, stands by definition with one foot in established institutional (in practicality often evangelical) Christianity, and the other in the commercial rock music industry. The subject of this paper is to study how this intermediate position is manifested and negotiated in Christian rock concerts. Such a performance of Christian rock music is here assumed to be both a rock concert and a religious service. The paper will examine how this duality is expressed in practices at Christian rock concerts. The research context of the study is, on the one hand, the sociology of religion, and on the other, the small but growing field of the study of religion and popular culture. The sociology of religion discusses the role and posi- tion of religion in contemporary society and culture. The duality of Chris- tian rock and Christian rock concerts, being part of both a traditional religion and a modern medium and business, is understood here as a concrete exam- ple of the relation of religion to modern society. The study of the relations between religion and popular culture seems to have been a latent field within research on religion at least since the 1970s, when the possibility of the research topic was suggested in a pioneer volume by John Nelson (1976). -

Eligibility Breed Owner(S)

2017 AKC Rally® National Championship Eligibility List As of December 22, 2016 Eligibility Breed Owner(s) Novice Afghan Hound DC Asia Soraya Tazi Of Suni RA SC THD CGC Claudia Jakus/Lynda Hicks Novice Afghan Hound Arcana Wicked Demon Hunter RN Alice Donoho/Chuck Milne Novice Afghan Hound GCH CH Mahrani's Wish U Luv At Stormhill BN RN JC CGC Mary Offerman/Sandra Frei/Terri Vanderzee/Sandi Nickolls Novice Airedale Terrier Miller's Marsh Second Chance RN Jane A. Miller Novice Airedale Terrier Plum Perfect's Conquer The World RN OAP NJP NFP Ms. Suzanne P Tharpe Novice Akita GCH CH Shebogi She Shoots And Scores RN Patti Pulkowski/Dave Pulkowski Novice Akita CH Mystik Gekko Sweetheart Of The Rodeo RN CGC Monica Colvin/Gregory B Colvin USAF (Ret.) Novice Alaskan Malamute Powderhound's Woo The Masses RN OA NAJ NF Dustin Smyka-Warner/Jennifer L Effler-Leveille Novice Alaskan Malamute GCH CH Spectre's Just Keep Talkin' RN Julia Cole Novice Alaskan Malamute CH Peace River's Dream Girl At Hallstatt RN Laura Maffei/Michele S Coburn Novice Alaskan Malamute Powderhound's Over And Over Again RN Jennifer L Effler-Leveille Novice Alaskan Malamute CH Illusion's One Man Show BN RN Pamela A Fusco/Joseph Fusco Novice All American Dog MEEKO CD RN CASEY SCHEIDEGGER/CJ SCHEIDEGGER Novice All American Dog Shameless Kid Cody RN MX MXJ NF CGCA KELLY LANE CASTLE Novice All American Dog Charlie VI RN MX MXJ Lindy Luopa Novice All American Dog Boe RN Joe Harrison Novice All American Dog Riley XIII RN NA NAJ AXP AJP LOIS LAMONT Novice All American Dog Texas Bella RA -

Mountain Shepherd

Newsletter of the The Salem United Methodist Church — Wolfsville MMoouunnttaaiinn SShheepphheerrdd Volume 30 June 2012 Number 6 Salem is planning to attend Creation 2012 4 DAYS in MT. UNION, PA Salem United Methodist Church—Wolfsville INSIDe More info at www.creationfest.com/ne Vicki Robinson helps n By Sue Ellen Stottlemyer paint the new pavilion CREATION 2012 is just around the corner. Main Stage Lineup More pavilion photos As of this writing, 13 youth and adults are • Switchfoot • Newsboys on page 10 planning to attend. • tobyMac • Kutless Creation, a Christian music festival • David Crowder • Red held at the Agape Farm, Mt. Union, • Chris Tomlin • Family Force 5 Pennsylvania, starts on Wednesday, June • Tenth Avenue North • Bread of Stone Missions . 2 27, and runs through Saturday evening, • Thousand Foot Krutch ... more Senior Appreciation Lunch . 3 June 30, 2012. Fringe Stage Lineup Attendance & Offerings . 4 Everyone who has attended in the past • Love and Death • Sent By Ravens Board of Child Care Auxiliary 4 has had a great time. Creation 2012 promises • Disciple • Shonlock Calendar of Events . 5 to be everything as in the past; good fellow - • Supertones • An Epic No Less Caregiving Ministry . 5 ship, excellent worship services, good food, • Project 86 ... more Who’s Doing What, When? . 6 and most of all, good Christian music — so HM Stage Lineup It’s Your Day! . 6 don’t miss out on a good time to praise and • Demon Hunter • Sleeping Giant Inspirational Reading . 7 worship our Creator. • Underoath ... more Recipe . 7 Speakers From Our Pastor . 8 Salem will be there for the entire event • Reggie Dabbs • Nick Vujicic Hero’s Club .