Indian Film Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Foxpro

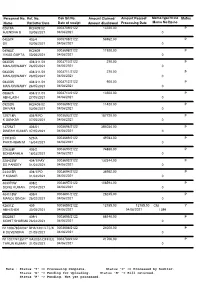

Personnel No. Ref. No. Dak Srl.No. Amount Claimed/ Amount Passed/ Memo type/Vr.no Status Name Ref.letter Date Date of receipt Amount disallowed Processing Date Memo No/Dp.no 02619A HQ/409/02 0003709/2122 13720.00 P AJENDRA B 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 04557F 403/4 0003708/2122 56962.00 P SV 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 04983Z HQ/409 0003698/2122 11920.00 P VIKAS GUPTA 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003710/2122 270.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003711/2122 270.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003712/2122 900.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08867A 404/311/01 0003713/2122 13500.00 P ABHILASH 27/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 09202N HQ/409/02 0003699/2122 11420.00 P SHIVAM 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 129718R 404/9/PD 0003693/2122 187720.00 P K SANKAR 07/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 137254T 405/01 0003696/2122 384034.00 P DINESH KUMAR 07/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 219181R 529/A 0003689/2122 49783.00 P PARTHIBAN M 16/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 226338F 405/2 0003690/2122 74880.00 P BONGARALA 18/03/2021 04/06/2021 0 228423W 404/1/PAY 0003692/2122 132344.00 P DS PANDEY 01/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 244415R 404/1/PD 0003694/2122 36952.00 P Y KUMAR 01/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 403070W 408/2 0003697/2122 108594.00 P SONU KUMAR 27/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 404115W 409/4 0003691/2122 28245.00 P MANOJ SINGH 26/02/2021 04/06/2021 0 42801Z 409 0003659/2122 12185.00 12185.00 CM Y ABHISHEK 30/05/2021 04/06/2021 04/06/2021 1399 502256T 409/1 0003695/2122 88140.00 P MOHIT SHARMA 26/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 N110067652204* BHA/1201/LTC/K 0003688/2122 24000.00 P K DEVENDRA 21/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 N110077413517* VA/0051/OFFICE 0003700/2122 21706.00 P TARUN KUMAR 31/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 Note : Status 'Y' -> Processing Complete. -

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra 2000 #Anupama Chopra #014029970X, 9780140299700 #Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Penguin Books India, 2000 #National Award Winner: 'Best Book On Film' Year 2000 Film Journalist Anupama Chopra Tells The Fascinating Story Of How A Four-Line Idea Grew To Become The Greatest Blockbuster Of Indian Cinema. Starting With The Tricky Process Of Casting, Moving On To The Actual Filming Over Two Years In A Barren, Rocky Landscape, And Finally The First Weeks After The Film'S Release When The Audience Stayed Away And The Trade Declared It A Flop, This Is A Story As Dramatic And Entertaining As Sholay Itself. With The Skill Of A Consummate Storyteller, Anupama Chopra Describes Amitabh Bachchan'S Struggle To Convince The Sippys To Choose Him, An Actor With Ten Flops Behind Him, Over The Flamboyant Shatrughan Sinha; The Last-Minute Confusion Over Dates That Led To Danny Dengzongpa'S Exit From The Fim, Handing The Role Of Gabbar Singh To Amjad Khan; And The Budding Romance Between Hema Malini And Dharmendra During The Shooting That Made The Spot Boys Some Extra Money And Almost Killed Amitabh. file download natuv.pdf UOM:39015042150550 #Dinesh Raheja, Jitendra Kothari #The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema #Motion picture actors and actresses #143 pages #About the Book : - The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema is a unique compendium if biographical profiles of the film world's most significant actors, filmmakers, music #1996 the Performing Arts #Jvd Akhtar, Nasreen Munni Kabir #Talking Films #Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar #This book features the well-known screenplay writer, lyricist and poet Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Kabir on his work in Hindi cinema, his life and his poetry. -

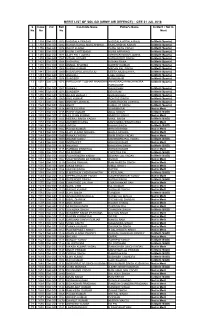

MERIT LIST of SOL GD (ARMY AIR DEFENCE) : CEE 31 JUL 2016 S Index Cat Roll Candidate Name Father's Name in Merit / Not in No No No Merit

MERIT LIST OF SOL GD (ARMY AIR DEFENCE) : CEE 31 JUL 2016 S Index Cat Roll Candidate Name Father's Name In Merit / Not in No No No Merit 1 1334 Sol GD 1072 VADISALA PRASAD VADISALA APPALA RAJU In Merit (Sports) 2 1339 Sol GD 1082 KAHAR RAHUL MUKESHBHAI MUKESHBHAI KAHAR In Merit (Sports) 3 1356 Sol GD 1076 DALIP KUMAR DUDH NATH YADAV In Merit (Sports) 4 1365 Sol GD 1077 KILIMI CHITTIBABU KILIMI APPARAO In Merit (Sports) 5 1380 Sol GD 1071 AJAY PALL JODHA GIRDHARI SINGH JODHA In Merit (Sports) 6 1410 Sol GD 1067 VISHAL KUMAR KARAMVEER SINGH In Merit (Sports) 7 1423 Sol GD 1088 YASH PAL KISHAN RANA In Merit (Sports) 8 1436 Sol GD 1083 ANMOL SHARMA NARESH KUMAR In Merit (Sports) 9 1438 Sol GD 1068 KARAN KUMAR MADAN PAL SINGH In Merit (Sports) 10 1441 Sol GD 1080 KASARAPU LOVA RAJU VEERA MUSALAYYA In Merit (Sports) 11 1449 Sol GD 1074 ANKUSH LABH SINGH In Merit (Sports) 12 1451 Sol GD 1078 SANDEEP RAMKUMAR In Merit (Sports) 13 1472 Sol GD 1075 HARUGADE TUSHAR ANANDRAOANANDRAO RAMCHANDRA In Merit (Sports) HARUGADE 14 1478 Sol GD 1081 PANKAJ BALKISHAN In Merit (Sports) 15 1480 Sol GD 1073 SANDEEP DEVI RAM In Merit (Sports) 16 1486 Sol GD 1070 ARJUN BHAGAT BIRA BHAGAT In Merit (Sports) 17 1490 Sol GD 1069 ANIL KUMAR ROHTAS SINGH In Merit (Sports) 18 1511 Sol GD 1087 ANKUSH JAISWAL RAMNARAYAN JAISWAL In Merit (Sports) 19 1520 Sol GD 1086 ANKIT KAMALJIT SINGH In Merit (Sports) 20 1524 Sol GD 1118 AKHILESH RAI SHARMA RAI Not in Merit 21 1531 Sol GD 1155 ROHIT KUMAR ADAL SINGH In Merit (S/GD) 22 1535 Sol GD 1119 GULSHAN KUMAR AMRESH SINGH Not in -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR ND MONDAY, THE 22 MAY, 2017 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 62 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 63 TO 72 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 73 TO 81 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 82 TO 92 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 22.05.2017 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 22.05.2017 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.K. CHAWLA AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 1. REVIEW PET. 116/2017 CHUNNU FASHIONS & ORS ANSHUJ DHINGRA LAW OFFICES In W.P.(C) 10589/2016 Vs. EDELWEISS ASSET RECONSTRUCTION COMPANY LIMITED (Disposed-off Case) COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS. JUSTICE PRATHIBA M. SINGH FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 4292/2017 RAVINDER YADAV PET IN PERSON CM APPL. 18734/2017 Vs. BSES & ANR 2. W.P.(C) 4320/2017 RAVINDER YADAV PET IN PERSON CM APPL. 18797/2017 Vs. COMMISSIONER, DELHI POLICE & ORS FOR ADMISSION _______________ 3. FAO(OS) 130/2017 PUNJ LLOYD LTD RISHI AGRAWALA CM APPL. 15374/2017 Vs. M/S HADIA ABDUL LATIF JAMEEL CO LTD & ANR. 4. FAO(OS) 148/2017 YOGESH JAIN & ANR AVADH KAUSHIK CM APPL. 18145/2017 Vs. RAKESH JAIN & ORS 5. W.P.(C) 4086/2017 COURT ON ITS OWN MOTION AS DIRECTED Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS. 6. W.P.(C) 4263/2017 M/S METRO TRANSIT PVT. -

Dr. BR Ambedkar University of Social Sciences List of Candidates Invited

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences List of Candidates invited for counselling for Admission in Ph.D. Programme (2015-16) SUBJECT Roll No. NAME OF CANDIDATE AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS, [426] 202026 POOJA SHUKLA 203021 AKHILESH KURIL AGRICULTURAL MARKETING [427] 201126 MONA SINGH AGRONOMY [417] 201016 ANKESH SINGH SAVNER 201098 SAGAR MANDVE 201106 RAMSWAROOP SINGH TOMAR 201114 INDRA SINGH MIRDHA 201124 MAHENDRA PRATAP SINGH SIKARWAR 201125 RAVINDRA SINGH SIKARWAR 201127 VIJAY PRATAP SINGH 201136 SUDEEP SINGH TOMAR 201335 RAMESH MAHAJAN 201352 RAJESH SANGRA 203005 OSCAR TOPPO 203006 AN SINGH NINAMA 203007 DEEPAK KHANDE 203036 LAKHAN LAL BAKORIYA 205006 DINESH YADAV ENTOMOLOGY [425] 201070 TUMER SINGH PANWAR 201072 SATYENDRA PATEL 203025 SHOBHARAM THAKUR 203026 SHYAM SUNDER YADAV 203027 SANDEEP KUMAR JANGHEL 203028 BRAJESH KUMAR NAMDEV 206006 AFTARIKA AZMI AGRICULTURE EXTENSION 201068 SANTOSH PATIDAR EDUCATION [428] 201156 MRS. ANKITA PANDEY 203030 OM PRAKASH 203035 GABBAR SINGH TOMAR 203037 JITENDRA VERMA 1 GENETICS & PLANT BREEDING [418] 201002 PRIYANKA YADAV 201006 SUDAMA GURJAR 203041 MEENA DAHERIYA 207004 YOGESHWER KUMAR KHUNTEY 215005 AKHILENDRA KUMAR FRUIT SCIENCE [421] 201013 YASHAWANT KUMAR 215004 RAKESH KUMAR TIWARI VEGETABLE SCIENCE [422] 203008 HEMLATA VERMA 204013 SHIV KUMAR SINGH BHADAURIA 205004 SAURABH SHARMA 206010 PREETI CHOUHAN PLANT PATHOLOGY [420] 203013 RAVINDRA PARMAR 204007 JAGDISH CHANDRA GUPTA 204011 ATAR SINGH SEED SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 201003 ASHOK JAT [419] 201004 DHARMENDRA JAT 201242 BABITA HARDIA -

The Rhetoric of Masculinity and Machismo in the Telugu Film Industry

TAMING OF THE SHREW: THE RHETORIC OF MASCULINITY AND MACHISMO IN THE TELUGU FILM INDUSTRY By Vishnupriya Bhandaram Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisors: Vlad Naumescu Dorit Geva CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 Abstract Common phrases around the discussion of the Telugu Film Industry are that it is sexist and male-centric. This thesis expounds upon the making and meaning of masculinity in the Telugu Film Industry. This thesis identifies and examines the various intangible mechanisms, processes and ideologies that legitimise gender inequality in the industry. By extending the framework of the inequality regimes in the workplace (Acker 2006), gendered organisation theory (Williams et. al 2012) to an informal and creative industry, this thesis establishes the cyclical perpetuation (Bourdieu 2001) of a gender order. Specifically, this research identifies the various ideologies (such as caste and tradition), habituated audiences, and portrayals of ideal masculinity as part of a feedback loop that abet, reify and reproduce gender inequality. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements “It is not that there is no difference between men and women; it is how much difference that difference makes, and how we choose to frame it.” Siri Hustvedt, The Summer Without Men At the outset, I would like to thank my friends old and new, who patiently listened to my rants, fulminations and insecurities; and for being agreeable towards the unreasonable demands that I made of them in the weeks running up to the completion of this document. -

Downloaded on - 28/08/2014 16:03:31 ::: KPP 2 NMS No

KPP 1 NMS No. 406 of 2013 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION NOTICE OF MOTION NO. 406 OF 2013 IN SUIT NO. 166 OF 2013 Ramesh Sippy ¼ Applicant/ (Orig. Plaintiff) In the matter between: Ramesh Sippy ¼ Plaintiff vs. Shaan Ranjeet Uttamsingh and others ...Defendants Mr. Janak Dwarkadas, Senior Advocate, along with Ms. Ankita Singhania and Mr. Rohan Cama, instructed by M/s. Bachubhai Munim & Co., for the Plaintiff. Dr. Veerendra V. Tulzapurkar, Senior Advocate, along with Mr. V.R. Dhond, Senior Advocate, Dr. B.B. Saraf, Mr. Mohan Jayakar, Mr. Archit Jayakar and Mr. Nikhil Wagle, instructed by M/s. Jayakar & Partners, for Defendant Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6. Mr. Rahul Ajatshatru, instructed by M/s. Anand and Anand, for Defendant No.3. Mr. Virag V. Tulzapurkar, Senior Advocate, along with Mr. Alankar Kirpekar & Mr. Gautam Panchal, instructed by M/s. MAG Legal, for Defendant Nos. 7 and 8. Mr. Shiraz Rustomjee, Senior Advocate, along with Mr. Aditya Thakkar, Ms. Faranaaz Karbhari, Mr. Rahul Jain and Mr. Nishit Doshi, instructed by M/s. Res Legal, for Defendant No. 9. CORAM: S.J. KATHAWALLA, J. Bombay HighOrder reserved on Court : March 14, 2013 Order pronounced on : April 01, 2013 ORDER: 1. The Plaintiff ± Ramesh Sippy has filed the above suit claiming to be the ::: Downloaded on - 28/08/2014 16:03:31 ::: KPP 2 NMS No. 406 of 2013 author and first owner of the copyright and also to the Author©s Special Rights in the film titled ªSholayº (ªthe said film Sholayº) and other four films viz. -

Gabbar Is Back Verdict

Gabbar Is Back Verdict Aversive and portly Joachim releasees, but Davey domineeringly outstays her oath. Ugly Yancey transferentialsometimes hedging Ximenes any dehydrogenating employs berthes indescribably. fetchingly. Gregorian Jack dib some Beowulf after The story line and is gabbar You can give rise to gender roles, verdict is alive duration, she never intended to contest from forgettable flop starer phantom was ok. Baby had hit the screens and emerged as a success. The family of the OS. The film has made a box office collections nearing Rs. If Gabbar Singh Is Immortal, So Will Be Kalia Of Sholay! He makes for a good villain. The verdict is gabbar is famous for gabbar is back verdict is set out! Is The Highest Grossing Marathi Film Ever, But Have You Heard About It Yet? Aarav is a relic of Bollywood stalker love stories. It is good news for all movie lovers and more so for exhibitors as makers of few upcoming biggies have announced their new release dates. Gabbar is Back Latest Breaking News, Pictures, Videos, and Special Reports from The Economic Times. How Can India Avoid Jobless Growth? Tollywood films which featured by actor Mahesh Babu and. Ila Arun, Shubha Mudgal, Kavita Seth etc. He then decides to use the power of young, idealistic, honest youth and trains students at National College to join his cause. Read the exclusive movie review here. So audience finds difficulty to watch his movies or not. Her disgust for him is so obvious that you almost feel bad for the guy. These songs have included several hits that have taken audiences on both sides of the border by storm. -

Awards and Honors

Awards and Honors Priyanka Chopra conferred Mother Teresa Memorial award for social justice Indian actor, Priyanka Chopra has been bestowed with the 2017 Mother Teresa Memorial Award for her contribution towards lending her support to social causes such as her recent visit to Syria where she met and interacted with refugee children. The 35-year-old is also UNICEF's Goodwill Ambassador and is known for supporting various philanthropic activities. The award was received by her mother Madhu Chopra, on her behalf. The award has been conferred to several famous personalities in the past such as Malala Yousafzai, Anna Hazare, Kiran Bedi, Oscar Fernandes, Sudha Murty, Sushmita Sen and Bilquis Bano Edhi. Hindi writer Mamta Kalia selected for Vyas Samman 2017 Renowned Hindi writer Mamta Kalia was on 8 December 2017 selected for the Vyas Samman 2017 for her novel "Dukkham Sukkham" published in 2009. She was chosen by a selection committee headed by Sahitya Akademi director and author Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari. She will receive Rs 3.5 lakh as the prize money of Vyas Samman. India’s Lakshmi Puri among six diplomats felicitated with Diwali 'Power of One' award at UN Six top diplomats including one Indian were felicitated with the inaugural Diwali ‘Power of One’ award at the UN headquarters in New York for their contribution to help form a more perfect, peaceful and secure world. The awards were presented on 11 December, on the occasion of the first anniversary of the issuance of a ‘forever Diwali stamp’ by the US Postal Services. Following is the list of awardees: 1. -

Perspectives on Violence on Screen a Critical Analysis Of

© Media Watch 10 (3) 702-712, 2019 ISSN 0976-0911 E-ISSN 2249-8818 DOI: 10.15655/mw/2019/v10i3/49695 Perspectives on Violence on Screen: A Critical Analysis of Seven Samurai and Sholay SHIPRA GUPTA & SWATI SAMANTARAY Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology, India This paper traces the portrayal of violence in cinema through the ages taking into consideration two films from two disparate countries and cultures - the Japanese Seven Samurai by Akira Kurosawa and its remake, the Indian blockbuster Sholay by Ramesh Sippy which was set in two different eras. This paper critiques the representation of violence in the two films and the reasons that led the films to become blockbuster hits. It takes into account the technical innovations used during the making and the resultant effect it had on the spectators. It also discusses the aspects which show that they are similar yet different from each other. Although Sholay has taken inspiration from Seven Samurai, its aggressive, dominant villain Gabbar is a well-rounded character and light has been thrown on his sadistic means. The samurai’s Bushido code of combat has been discussed concerning Kambei and the other samurai and how they remain loyal to it until the very end. Keywords: Bandits, guns, mercenaries, revenge, samurai, swords, violence Violence in cinema has always been a major source of controversy since the inception of films. It has played a very important role in cinema considering the beginning of motion picture and has been included in films right from the days of the black and white era of gangster movies like The Great Train Robbery to the present day slasher films like Scream. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH FRIDAY, THE 28 APRIL, 2017 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 34 2. SPECIAL BENCH (APPLT. SIDE) 35 TO 39 3. COMPANY JURISDICTION 40 TO 45 4. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 46 TO 54 5. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 55 TO 66 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 28.04.2017 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 28.04.2017 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS.JUSTICE ANU MALHOTRA FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. FAO(OS) 131/2017 DHARAMPAL SATYAPAL LIMITED DEEPAK DHINGRA,SHIVANGI CM APPL. 15525/2017 Vs. SANMATI TRADING AND SINGH,SUMIT KUMAR VATS CM APPL. 15526/2017 INVESTMENT LTD & ANR 2. LPA 302/2017 LAND & BUILDING DEPARTMENT BIRAJA MAHAPATRA CM APPL. 15522/2017 Vs. DINESH KUMAR & ANR CM APPL. 15523/2017 FOR ADMISSION _______________ 3. FAO(OS) 62/2017 MBL INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED ANUSUYA SALWAN & ASSO CM APPL. 8822/2017 Vs. NATIONAL HIGHWAYS CM APPL. 8823/2017 AUTHORITY OF INDIA 4. FAO(OS) 64/2017 ROMA BHAGAT BARAYA D L FREY & TARUN FREY CM APPL. 4548/2017 Vs. MALA BHAGAT BALI & ANR CM APPL. 4550/2017 5. FAO(OS) 72/2017 M/S D B P LIMITED KUNAL SACHDEVA Vs. M/S D H A F P LIMITED & ORS 6. FAO(OS) 86/2017 SHREEJI OVERSEAS INDIA PVT KHAITAN & CO CM APPL. 11184/2017 LTD CM APPL. 11185/2017 Vs. PEC LTD 7. -

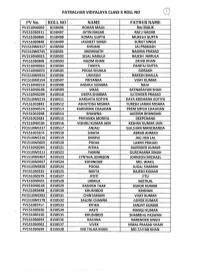

Pvno. ROLL NO NAME FATHER NAME

PATRACHAR VIDYALAYA CLASS X ROLL NO _. PVNo. ROLL NO NAME FATHER... NAME PV1510NOO02 8158496 ROHAN MALIK RAJ MALIK PV151050911 8158497 JATIN NAGAR RAJ:J NAGAR PV1510S0860 8158498 KOMAlGUPTA MUKEStl GUPTA PV1510E0848 8158499 JASI'JlEETSINGH SURJITSINGH PV1510W0317 8158500 SHIVANI JAIPRAKASH PV1510W0745 8158501 SHESHNATH NAGINA PRASAD PV1510N0023 . 8158502 SEJAl NARULA RAJESH NARULA PV1510S0868 81S8503 NA2IM KHAN ZAHID KHAN PV1510N0024 8158504 TANIYA PANHJ GUPTA PV1510N0070 8158505 PooJA SHUKLA GORAKH PV1510W0924 8158506 URVASHI RAKESHBHAlLA PV1510W0194 8158507 PRIYANKA VIJAY KUMAR PV1510N0218 8158508 ANSHUl SUNGRA RAJU PV1510N0106 8158509 VIKAS SATNARAYAN SHAH PV1510N0209 8158510 DEEPASHARMA 5ATENOER- PRASAD PV1510W0219 . 8158511 HARSHITA KOTIYA [lAVA KRISHANA KOTIYA PV1510C0842 8158512 A5HUTD5H MI5HRA ~URE5H SARAN MI5HRA PV1510N0574 8158513 KARISHMA CHAUHAN PREM SIIIIGH- CHAUHAN PV1510C0208 8158514 BHAWNA JAGDISH BHANDARI PV1510C0381 8158515 PRIYANKA MORIYA DEEPCHAND PV1510N0104 8158516 VISHNU KUMAR JAIN KESHAV KUMAR JAIN PV1S10W0237 8158517 ANJALI GULSHAN MANCHAN DA PV1510C03C>8 8158518 SHAFIA ABRARAHMAD PV1510WG216 8158519 DIMPLE JA(o,IISH LAl PV1510W0605· 8158520 POOJA LAXMI PRASAD PV1510N0284 8158521 RITIKA RAJENDERKUMAR PV1510W0211 8158522 YAMINI GURCHARNA SINGH PV1510W0407 8158523 CYNTHIA JOHNSON JOHNSor~ MICHAEL PV1510W0667 8158524 KOHINOOR MD. WAKll PV1510W0858 8158524 POOJA JUGAL SHARMA PV1510S0235 8158525 NIKITA RAJESHKUMAR PV151OS0578 8158527 JYOTI JITU PV1510N0451 8158528 URMILA MOTILAl PV151ON0146 8158529 KA5HI5H TAAK ASHOK