Perspectives on Violence on Screen a Critical Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Foxpro

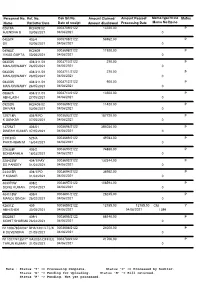

Personnel No. Ref. No. Dak Srl.No. Amount Claimed/ Amount Passed/ Memo type/Vr.no Status Name Ref.letter Date Date of receipt Amount disallowed Processing Date Memo No/Dp.no 02619A HQ/409/02 0003709/2122 13720.00 P AJENDRA B 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 04557F 403/4 0003708/2122 56962.00 P SV 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 04983Z HQ/409 0003698/2122 11920.00 P VIKAS GUPTA 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003710/2122 270.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003711/2122 270.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08300N 404/311/01 0003712/2122 900.00 P MANJUSWAMY 26/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 08867A 404/311/01 0003713/2122 13500.00 P ABHILASH 27/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 09202N HQ/409/02 0003699/2122 11420.00 P SHIVAM 03/06/2021 04/06/2021 0 129718R 404/9/PD 0003693/2122 187720.00 P K SANKAR 07/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 137254T 405/01 0003696/2122 384034.00 P DINESH KUMAR 07/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 219181R 529/A 0003689/2122 49783.00 P PARTHIBAN M 16/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 226338F 405/2 0003690/2122 74880.00 P BONGARALA 18/03/2021 04/06/2021 0 228423W 404/1/PAY 0003692/2122 132344.00 P DS PANDEY 01/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 244415R 404/1/PD 0003694/2122 36952.00 P Y KUMAR 01/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 403070W 408/2 0003697/2122 108594.00 P SONU KUMAR 27/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 404115W 409/4 0003691/2122 28245.00 P MANOJ SINGH 26/02/2021 04/06/2021 0 42801Z 409 0003659/2122 12185.00 12185.00 CM Y ABHISHEK 30/05/2021 04/06/2021 04/06/2021 1399 502256T 409/1 0003695/2122 88140.00 P MOHIT SHARMA 26/04/2021 04/06/2021 0 N110067652204* BHA/1201/LTC/K 0003688/2122 24000.00 P K DEVENDRA 21/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 N110077413517* VA/0051/OFFICE 0003700/2122 21706.00 P TARUN KUMAR 31/05/2021 04/06/2021 0 Note : Status 'Y' -> Processing Complete. -

Global Media Journal–Pakistan Edition Vol.Xii, Issue-01, Spring, 2019 1

GLOBAL MEDIA JOURNAL–PAKISTAN EDITION VOL.XII, ISSUE-01, SPRING, 2019 Screen Adaptation: An Art in Search of Recognition Sharaf Rehman1 Abstract This paper has four goals. It offers a brief history and role of the process of screen adaptation in the film industries in the U.S. and the Indian Subcontinent; it explores some of the theories that draw parallels between literary and cinematic conventions attempting to bridge literature and cinema. Finally, this paper discusses some of the choices and strategies available to a writer when converting novels, short stories, and stage play into film scripts. Keywords: Screen Adoption, Subcontinent Film, Screenplay Writing, Film Production in Subcontinent, Asian Cinema 1 Professor of Communication, the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, USA 1 GLOBAL MEDIA JOURNAL–PAKISTAN EDITION VOL.XII, ISSUE-01, SPRING, 2019 Introduction Tens of thousands of films (worldwide) have their roots in literature, e.g., short stories and novels. One often hears questions like: Can a film be considered literature? Is cinema an art form comparable to paintings of some of the masters, or some of the classics of literature? Is there a relationship or connection between literature and film? Why is there so much curiosity and concern about cinema? Arguably, no other storytelling medium has appealed to humanity as films. Silent films spoke to audiences beyond geographic, political, linguistic, and cultural borders. Consequently, the film became the first global mass medium (Hanson, 2017). In the last one hundred years, audiences around the world have shown a boundless appetite for cinema. People go to the movies for different social reasons, and with different expectations. -

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra 2000 #Anupama Chopra #014029970X, 9780140299700 #Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Penguin Books India, 2000 #National Award Winner: 'Best Book On Film' Year 2000 Film Journalist Anupama Chopra Tells The Fascinating Story Of How A Four-Line Idea Grew To Become The Greatest Blockbuster Of Indian Cinema. Starting With The Tricky Process Of Casting, Moving On To The Actual Filming Over Two Years In A Barren, Rocky Landscape, And Finally The First Weeks After The Film'S Release When The Audience Stayed Away And The Trade Declared It A Flop, This Is A Story As Dramatic And Entertaining As Sholay Itself. With The Skill Of A Consummate Storyteller, Anupama Chopra Describes Amitabh Bachchan'S Struggle To Convince The Sippys To Choose Him, An Actor With Ten Flops Behind Him, Over The Flamboyant Shatrughan Sinha; The Last-Minute Confusion Over Dates That Led To Danny Dengzongpa'S Exit From The Fim, Handing The Role Of Gabbar Singh To Amjad Khan; And The Budding Romance Between Hema Malini And Dharmendra During The Shooting That Made The Spot Boys Some Extra Money And Almost Killed Amitabh. file download natuv.pdf UOM:39015042150550 #Dinesh Raheja, Jitendra Kothari #The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema #Motion picture actors and actresses #143 pages #About the Book : - The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema is a unique compendium if biographical profiles of the film world's most significant actors, filmmakers, music #1996 the Performing Arts #Jvd Akhtar, Nasreen Munni Kabir #Talking Films #Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar #This book features the well-known screenplay writer, lyricist and poet Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Kabir on his work in Hindi cinema, his life and his poetry. -

Printing Office

Chapter 16 MAINTENANCE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT INTRODUCTION Aviation maintenance is a complex and demanding endeavor. Its success, which is ultimately measured by the safety of the flying public, depends on communication and teamwork. Aviation maintenance operations are most successful when crews function as integrated, communicating teams -- rather than as a collection of individuals engaged in independent actions. Over the past decade, the importance of teamwork in the maintenance setting has been widely recognized.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The result has been the emergence of human factors training, Maintenance Resource Management (MRM) programs, and other team-centered activities within the aviation maintenance community. Maintenance Resource Management is a general process for improving communication, effectiveness, and safety in airline maintenance operations. Effectiveness is measured through the reduction of maintenance errors, and improved individual and unit coordination and performance. MRM is also used to change the "safety culture" of an organization by establishing a pervasive, positive attitude toward safety. Such attitudes, if positively reinforced, can lead to changed behaviors and better performance. Safety is typically measured by occupational injuries, ground damage incidents, reliability, and airworthiness. MRM improves safety by increasing the coordination and exchange of information between team members, and between teams of airline maintenance crews. The details of MRM programs vary from organization to organization. However, all MRM programs link and integrate traditional human factors topics, such as equipment design, human physiology, workload, and workplace safety. Likewise, the goal of any MRM program is to improve work performance and safety. They do this by reducing maintenance errors through improved coordination and communication. -

World Cinema Through G G Obal

COSTANZO “A wonderful textbook as well as a scholarly tour-de-force. Costanzo brings new meaning to the concept of global genres and offers up examples that convincingly demonstrate cinematic border crossings and cultural connections amongst far- flung places.” David Desser, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, USA “Costanzo revitalizes both world cinema and genre studies with his stimulating, WORLD insightful cross cultural approach to warrior heroes, wedding films, horror and road WORLD CINEMA movies. It’s a well-written, scholarly work that’s as inventive as it is enjoyable.” Diane Carson, Past President, University Film and Video Association (UFVA) “William Costanzo has cut the clearest path yet through the forest of World CINEMA Cinema. Key genres take us confidently place to place, era to era; while maps, timelines, and surveys of national industries position a rich array of films, many analyzed with real mastery.” Dudley Andrew, Professor of Film and Comparative Literature, Yale University, USA THROUGH World Cinema through Global Genres offers a new response to recent trends in internationalism that shape the increasingly global character of movies. Costanzo is able to render the complex forces of global filmmaking accessible to students; instead of tracing the long histories of cinema country by country, this innovative textbook uses engaging, recent films like Hero (China), Monsoon THROUGH THROUGH G LOBAL Wedding (India), and Central Station (Brazil) as entry points, linking them to comparable American and European films. The book’s cluster-based organization allows students to acquire a progressively sharper understanding of core issues about genre, aesthetics, industry, culture, history, film theory, and representation that apply to all films around the world. -

October 2016

October 2016 9:00 PM ET/6:00 PM PT 7:20 PM ET/4:20 PM PT 11:15 PM ET/8:15 PM PT 8:00 PM CT/7:00 PM MT 6:20 PM CT/5:20 PM MT 10:15 PM CT/9:15 PM MT Guns of the Magnificent Seven The Forgotten I.Q. 10:35 PM ET/7:35 PM PT 9:00 PM ET/6:00 PM PT SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1 9:35 PM CT/8:35 PM MT 8:00 PM CT/7:00 PM MT SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2 12:20 AM ET/9:20 PM PT The X-Files Great Balls Of Fire 11:20 PM CT/10:20 PM MT 1:05 AM ET/10:05 PM PT 12:05 AM CT/11:05 PM MT 10:50 PM ET/7:50 PM PT 9:50 PM CT/8:50 PM MT Die Hard The Magnificent Seven MONDAY, OCTOBER 3 2:40 AM ET/11:40 PM PT 12:40 AM ET/9:40 PM PT Sixteen Candles 1:40 AM CT/12:40 AM MT 3:15 AM ET/12:15 AM PT 11:40 PM CT/10:40 PM MT 2:15 AM CT/1:15 AM MT The Deer Hunter Guns of the Magnificent Seven The Forgotten TUESDAY, OCTOBER 4 5:50 AM ET/2:50 AM PT 2:15 AM ET/11:15 PM PT 12:25 AM ET/9:25 PM PT 4:50 AM CT/3:50 AM MT 5:05 AM ET/2:05 AM PT 1:15 AM CT/12:15 AM MT 11:25 PM CT/10:25 PM MT 4:05 AM CT/3:05 AM MT The Trailer Show Ravenous The X-Files Great Balls Of Fire 6:00 AM ET/3:00 AM PT 4:25 AM ET/1:25 AM PT 2:15 AM ET/11:15 PM PT 5:00 AM CT/4:00 AM MT 6:50 AM ET/3:50 AM PT 3:25 AM CT/2:25 AM MT 1:15 AM CT/12:15 AM MT 5:50 AM CT/4:50 AM MT Harry and the Hendersons Arthur and the Invisibles 2: The Legend Sixteen Candles 7:55 AM ET/4:55 AM PT 6:00 AM ET/3:00 AM PT 3:50 AM ET/12:50 AM PT 6:55 AM CT/5:55 AM MT Revenge of Maltazard 5:00 AM CT/4:00 AM MT 2:50 AM CT/1:50 AM MT 8:30 AM ET/5:30 AM PT The Magnificent Seven 7:30 AM CT/6:30 AM MT The Legend of Zorro Dazed and Confused 10:10 AM ET/7:10 AM PT 8:15 AM ET/5:15 AM PT 5:35 AM ET/2:35 AM PT 9:10 AM CT/8:10 AM MT The Trailer Show 7:15 AM CT/6:15 AM MT 4:35 AM CT/3:35 AM MT 8:40 AM ET/5:40 AM PT Guns of the Magnificent Seven 7:40 AM CT/6:40 AM MT The Mask of Zorro Robots 12:00 PM ET/9:00 AM PT 10:40 AM ET/7:40 AM PT 7:10 AM ET/4:10 AM PT 11:00 AM CT/10:00 AM MT Reservoir Dogs 9:40 AM CT/8:40 AM MT 6:10 AM CT/5:10 AM MT 10:25 AM ET/7:25 AM PT Harry and the Hendersons 9:25 AM CT/8:25 AM MT E.T. -

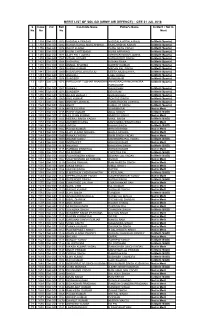

MERIT LIST of SOL GD (ARMY AIR DEFENCE) : CEE 31 JUL 2016 S Index Cat Roll Candidate Name Father's Name in Merit / Not in No No No Merit

MERIT LIST OF SOL GD (ARMY AIR DEFENCE) : CEE 31 JUL 2016 S Index Cat Roll Candidate Name Father's Name In Merit / Not in No No No Merit 1 1334 Sol GD 1072 VADISALA PRASAD VADISALA APPALA RAJU In Merit (Sports) 2 1339 Sol GD 1082 KAHAR RAHUL MUKESHBHAI MUKESHBHAI KAHAR In Merit (Sports) 3 1356 Sol GD 1076 DALIP KUMAR DUDH NATH YADAV In Merit (Sports) 4 1365 Sol GD 1077 KILIMI CHITTIBABU KILIMI APPARAO In Merit (Sports) 5 1380 Sol GD 1071 AJAY PALL JODHA GIRDHARI SINGH JODHA In Merit (Sports) 6 1410 Sol GD 1067 VISHAL KUMAR KARAMVEER SINGH In Merit (Sports) 7 1423 Sol GD 1088 YASH PAL KISHAN RANA In Merit (Sports) 8 1436 Sol GD 1083 ANMOL SHARMA NARESH KUMAR In Merit (Sports) 9 1438 Sol GD 1068 KARAN KUMAR MADAN PAL SINGH In Merit (Sports) 10 1441 Sol GD 1080 KASARAPU LOVA RAJU VEERA MUSALAYYA In Merit (Sports) 11 1449 Sol GD 1074 ANKUSH LABH SINGH In Merit (Sports) 12 1451 Sol GD 1078 SANDEEP RAMKUMAR In Merit (Sports) 13 1472 Sol GD 1075 HARUGADE TUSHAR ANANDRAOANANDRAO RAMCHANDRA In Merit (Sports) HARUGADE 14 1478 Sol GD 1081 PANKAJ BALKISHAN In Merit (Sports) 15 1480 Sol GD 1073 SANDEEP DEVI RAM In Merit (Sports) 16 1486 Sol GD 1070 ARJUN BHAGAT BIRA BHAGAT In Merit (Sports) 17 1490 Sol GD 1069 ANIL KUMAR ROHTAS SINGH In Merit (Sports) 18 1511 Sol GD 1087 ANKUSH JAISWAL RAMNARAYAN JAISWAL In Merit (Sports) 19 1520 Sol GD 1086 ANKIT KAMALJIT SINGH In Merit (Sports) 20 1524 Sol GD 1118 AKHILESH RAI SHARMA RAI Not in Merit 21 1531 Sol GD 1155 ROHIT KUMAR ADAL SINGH In Merit (S/GD) 22 1535 Sol GD 1119 GULSHAN KUMAR AMRESH SINGH Not in -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq. -

Historical Disjunctures and Bollywood Audiences in Trinidad: Negotiations of Gender and Ethnic Relations in Cinema Going1

. Volume 16, Issue 2 November 2019 Historical disjunctures and Bollywood audiences in Trinidad: Negotiations of gender 1 and ethnic relations in cinema going Hanna Klien-Thomas Oxford Brookes University, UK Abstract: Hindi cinema has formed an integral part of the media landscape in Trinidad. Audiences have primarily consisted of the descendants of indentured workers from India. Recent changes in production, distribution and consumption related to the emergence of the Bollywood culture industry have led to disruptions in the local reception context, resulting in a decline in cinema-going as well as the diminishing role of Hindi film as ethnic identity marker. This paper presents results of ethnographic research conducted at the release of the blockbuster ‘Jab Tak Hai Jaan’. It focuses on young women’s experiences as members of a ‘new’ Bollywood audience, characterised by a regionally defined middle class belonging and related consumption practices. In order to understand how the disjuncture is negotiated by contemporary audiences, cinema-going as a cultural practice is historically contextualised with a focus on the dynamic interdependencies of gender and ethnicity. Keywords: Hindi cinema, Caribbean, Bollywood, Indo-Trinidadian identity, Indian diaspora, female audiences, ethnicity Introduction Since the early days of cinema, Indian film productions have circulated globally, establishing transnational and transcultural audiences. In the Caribbean, first screenings are reported from the 1930s. Due to colonial labour regimes, large Indian diasporic communities existed in the region, who embraced the films as a connection to their country of origin or ancestral homeland. Consequently, Hindi speaking films and more recently the products of the global culture industry Bollywood, have become integral parts of regional media landscapes. -

Copyrightability of Movie Characters

COPYRIGHTABILITY OF MOVIE CHARACTERS Tarun Kumar S J1 Introduction Movies have become a part of our daily lives and we also closely relate ourselves with various characters that we see on screen. Those fictional movie characters have a great level of commercial appeal and popularity among the public. This article is premised on the right of protection held by the creators of these characters. Copyrighting of movie characters helps in curbing the unauthorized exploitation of these creations. But this concept of legal protection has not been well-defined and not widely used in India. Here, the concept of copyrightability of characters and infringement of such copyrights are discussed. In addition to that, the option of trademarking of movie characters has also been explicated. Recent issues, judgments from various courts and the tests used by courts have been discussed to expound the concept of legal protection for movie characters. A comparison has been made between the US and Indian scenarios for better understanding of the concept and its intricacies. This article tends to explore the copyright law and the alternative doctrines protecting movie characters. Copyright Law Copyright is a right given by the law to creators of literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works and producers of cinematograph films and sound recordings. In fact, it is a bundle of rights including, inter alia, rights of 1 2nd year B.A., LLB student, ILS Law College, Pune reproduction, communication to the public, adaptation and translation of the work. There could be slight variations in the composition of the rights depending on the work. -

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21St Century

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century Neelam Sidhar Wright For my parents, Kiran and Sharda In memory of Rameshwar Dutt Sidhar © Neelam Sidhar Wright, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9634 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9635 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0356 6 (epub) The right of Neelam Sidhar Wright to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations of Film Titles viii 1 Introduction: The Bollywood Eclipse 1 2 Anti-Bollywood: Traditional Modes of Studying Indian Cinema 21 3 Pedagogic Practices and Newer Approaches to Contemporary Bollywood Cinema 46 4 Postmodernism and India 63 5 Postmodern Bollywood 79 6 Indian Cinema: A History of Repetition 128 7 Contemporary Bollywood Remakes 148 8 Conclusion: A Bollywood Renaissance? 190 Bibliography 201 List of Additional Reading 213 Appendix: Popular Indian Film Remakes 215 Filmography 220 Index 225 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the following people for all their support, guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout the course of researching and writing this book: Richard Murphy, Thomas Austin, Andy Medhurst, Sue Thornham, Shohini Chaudhuri, Margaret Reynolds, Steve Jones, Sharif Mowlabocus, the D.Phil. -

The Magnificent Seven Sculptors

THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN SCULPTORS STAND CO2 ART CENTRAL HONG KONG 27 MARCH - 1 APRIL 2018 CENTRAL HARBOR FRONT 01 Born in Victoria in 1976, Daniel Agdag is an Australian artist and flmmaker. The son of Armenian immigrants, Agdag studied fne art before turning his hand to flmmaking and receiving his Masters in Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2007. He will tell you that he makes things out of cardboard. He’s modest. This declaration in no way illuminates the delicate form and eccentric narrative of his work. To say he pushes the medium to its limits is an understatement. His process is very much akin to freehand drawing. He spends a great deal of time thinking and absorbing objects in the built environment, their peculiar details and functions, which leads him to form narratives. Once this is frmly resolved in his mind, various components of the work begin to slowly emerge, ftting together to compliment the overall idea. This narrative is the blueprint from which he works, it informs every component; it’s place, how each relates to the other, and most importantly, the proportions. The painstaking proportions, the key factor that drives his DANIEL AGDAG aesthetic. Like drawing, he builds the work up piece by ART CENTRAL HONG KONG piece, section by section, always assessing it in relation to the entirety of the parts. 27 MARCH - 1 APRIL The build is entirely intuitive, Agdag describes his process as ‘sketching with cardboard’, as he makes no detailed plans or drawings of the pieces he creates.