Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)* a Biographical Sketch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

Rabindranath Tagore's Model of Rural Reconstruction: a Review

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT.– DEC. 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Rabindranath Tagore’s Model of Rural Reconstruction: A review Dr. Madhumita Chattopadhyay Assistant Professor in English, B.Ed. Department, Gobardanga Hindu College (affiliated to West Bengal State University), P.O. Khantura, Dist- 24 Parganas North, West Bengal, PIN – 743273. Received: July 07, 2018 Accepted: August 17, 2018 ABSTRACT Rabindranath Tagore’s unique venture on rural reconstruction at Silaidaha-Patisar and at Sriniketan was a pioneering work carried out by him with the motto of the wholesome development of the community life of village people through education, training, healthcare, sanitation, modern and scientific agricultural production, revival of traditional arts and crafts and organizing fairs and festivities in daily life. He believed that through self-help, self-initiation and self-reliance, village people will be able to help each other in their cooperative living and become able to prepare the ground work for building the nation as an independent country in the true sense. His model of rural reconstruction is the torch-bearer of so many projects in independent India. His principles associated with this programme are still relevant in the present day world, but is not out of criticism. The need is to make critical analysis and throw new lights on this esteemed model so that new programmes can be undertaken based on this to achieve ‘life in its completeness’ among rural population in India. Keywords: Rural reconstruction, cooperative effort, community development. Introduction Rathindranath Tagore once said, his father was “a poet who was an indefatigable man of action” and “his greatest poem is the life he has lived”. -

L'adieu a La Vie, 130 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Amiel's Journal, 33

Index Abbott, Lyman, 16 Bauls,46 Achebe, Chinua, 141 Bedford Chapel, Bloomsbury, 11 L'Adieu ala Vie, 130 Beerbohm, Max, 18 African writers, 143 Bengal, 12, 13, 26, 27, 28, 51, 84, 88, Ajanta Cave paintings, 8, 113 100, 110, 145 Agriculture, 96 Bengal Academy, 145 Ahmedabad, 30 Bengal partition, 17 AJfano, Franco, 123 Bengal Renaissance, 50, 51, 52, 54 AJhambra Theatre, London, 123, Bengali language, 1, 8, 13, 27, 29, 35, 127 36,42,142 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Bengali literature, 3, 8, 9, 11, 14,29, Amiel's Journal, 33 33,35,36,37,38,39,42,114 Amritsar massacre, 128 Benjamin, Walter, 109 see also Jalianwalla Bagh Beowulf, 35 massacre, Berg,AJban, 131, 132, 133 Andersen, Hans Christian, 30 Berhampore Gessore), 27 Andrews, C. F., 63, 96, 99 Berlin, 133 Anderson, James Drummond, 8 Berlin Exhibition of Tagore's art, The Arabian Nights, 30, 79, 122 108 Argentina, 97 Bhanaphul (Wild Flower), 52 Aristotle, 38 Bhanusinha (pen-name of Aronson,AJex,l04 Rabindranath Tagore), 27 Art deco, 110 Bhiirati (Bengali journal), 31, 52 Art nouveau, 110 Bharatvasher Itihasha Dhara (A Vision The Artist, 115 of India's History), 58, 59 Asian languages, 142 Bhartrhari, 124 Asian literature, 143 Bhiisa Katha, 42 Asian Review, 20 Bhattacharya, Upendranath, 43 The Athenaeum (journal), 6, 17 Bidou, Henri, 106, 107 Attenborough, Richard, 153 Birdwood, Sir George, 7, 8 Aurobindo Ghose, 50 Birmingham Exhibition of Tagore's Art, 106 Bach, J. S., 106 Bisarjan (Sacrifice), 143 Baines, William, 127 see also Sacrifice Balak (Bengali journal), 31, 32 Blake, William, 6 Balej, -

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 Minutes)

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 minutes) Directed by Satyajit Ray Written byRabindranath Tagore ... (from the story "Nastaneer") Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Soumitra Chatterjee ... Amal Madhabi Mukherjee ... Charulata Shailen Mukherjee ... Bhupati Dutta SATYAJIT RAY (director) (b. May 2, 1921 in Calcutta, West Bengal, British India [now India]—d. April 23, 1992 (age 70) in Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films and TV shows, including 1991 The Stranger, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray (Short documentary), 1984 The Home and the World, 1984 (novel), 1979 Naukadubi (story), 1974 Jadu Bansha (lyrics), “Deliverance” (TV Movie), 1981 “Pikoor Diary” (TV Short), 1974 Bisarjan (story - as Kaviguru Rabindranath), 1969 Atithi 1980 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The (story), 1964 Charulata (from the story "Nastaneer"), 1961 Elephant God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 Bala, 1976 The Kabuliwala (story), 1961 Teen Kanya (stories), 1960 Khoka Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1973 Distant Thunder, Babur Pratyabartan (story - as Kabiguru Rabindranath), 1960 1972 The Inner Eye, 1972 Company Limited, 1971 Sikkim Kshudhita Pashan (story), 1957 Kabuliwala (story), 1956 (Documentary), 1970 The Adversary, 1970 Days and Nights in Charana Daasi (novel "Nauka Doobi" - uncredited), 1947 the Forest, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1967 The Naukadubi (story), 1938 Gora (story), 1938 Chokher Bali Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 “Two” (TV Short), 1965 The (novel), 1932 Naukadubi (novel), 1932 Chirakumar Sabha, 1929 Holy Man, 1965 The Coward, 1964 Charulata, 1963 The Big Giribala (writer), 1927 Balidan (play), and 1923 Maanbhanjan City, 1962 The Expedition, 1962 Kanchenjungha, 1961 (story). -

Http//:Daathvoyagejournal.Com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department Of

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.2, No.1, March, 2017 A Journey: From Nostohnirh to Charulata Shubhendu Shekhar Naskar Assistant Professor Department of English Basirhat College Email- [email protected] Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray are two high-flying names in the sky of art, culture and literature. They have glorified Bengal as well as India in the sphere of whole universe. Tagore wrote many legendary novels which were later taken as the scripts of Indian films. Such an epoch making novel of Tagore was Nostonirh (The Broken Nest) which was transformed into a film in the hand of renowned director, Satyajit Ray. Ray not only took the story, he also mixed the plot with his imagination. This compilation leads the novel to become almost a similar famous film in Bengali, ‘Charulata’. My article will try to highlight this artistic approach of Ray along with his adoption of the novel. Key words: Tagore, Ray, Nostonirh, Charulata, Bhupati, Amal. Rabindranath Tagore's stories exemplify his remarkable abilities to enter into the complexities of human relationships profoundly. Within the seemingly simple plots, he could explore the psychological aspects of his characters properly. They seem to be the true representatives of their time. As a result they bring out the sociological aspects of the then Bengali society. In his highly acclaimed novel Nostonirh (The Broken Nest), Tagore simply portrays with extraordinary compassion and lyricism the predicament of women in traditional Bengali contexts, through the loneliness of an intelligent, beautiful woman who is neglected by her husband. -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

Notes and References

Notes and References . Introduction 1. Eng. Translation by E. B. Cowell and A. E. Gough. Chowkhamba Publication , Varanasi (1961 ). 2. Ed. by Kameswarnath Misra, Chowkhamba Sanskrit · Series, Varanasi (1979). 3. Darsanani Sacjevatra mulabhedavyapeksaya Devatatattvabhedena jnatavyani manisibhih , Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, · Varanasi (1979), P. 3 .. 4. Satjdars'anasamuccya, P. 5 and P. 11. cf S. N. Das Gupta, History of Indian ofPhilosophy, Vol. V, Cambridge (1955), P. 9. 5. Bankimchandra Chattopadhyaya, A Popular Literature For Bengal (1970). Adapted from Bhabatosh Dutta, Bangalee Manose Vedanta (in Bengali), Sahityaloke, Calcutta (1986), PP. 2- 3. 6. Ward's report published in 1811 was later utilized by William Adam in his report of 1835. See his The State of Education in Bengal. Ed. By anathnath Basu, C. U. Publications( 1941 ), PP.18-19. 136 7. Dilip Kumar Biswas, "Rammohun Roy and Vedanta". Rammohun Samikhsa ,in Bengali (1983), PP. 131. 8. We have the mind the member of the faction led by Radhakanta Deb. 9. Cultural Heritage of India, Vol. III. Ed. by Haridas Bhattacharya. The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture (1953), PP .245 - 254. Also in ·Aspects of VedCinta, Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, Calcutta, (1995), PP. 78-90. 10 "The Religion of the Spirit and the World's need: Fragments of a Confession". In the Philosophy of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed. by P. A. Schilpp, N.Y. (1952), PP. 5-82. 11 Eastern Religions and Western Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1939), P.24. 12 Europe reconsidered-Perceptions ofthe West in Nineteenth Century. Delhi: Oxford University Press (1988), P. 3. 13 Mark, K. and Engels, F., German Ideology inThe Collected Works of Marx and Engels, Vol. -

Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: a Study of Social and Religious Perspective

British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 2(3), 60-72, 2020 Publisher homepage: www.universepg.com, ISSN: 2663-7782 (Online) & 2663-7774 (Print) https://doi.org/10.34104/bjah.020060072 British Journal of Arts and Humanities Journal homepage: www.universepg.com/journal/bjah Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: A Study of Social and Religious Perspective Ruksana Karim* Department of Music, Faculty of Arts, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. *Correspondence: [email protected] (Ruksana Karim, Lecturer, Department of Music, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh) ABSTRACT This paper describes how South Asian folk music figured out from the ancient era and people discovered its individual form after ages. South Asia has too many colorful nations and they owned different culture from the very beginning. Folk music is like a treasure of South Asian culture. According to history, South Asian people established themselves here as a nation (Arya) before five thousand years from today and started to live with native people. So a perfect mixture of two ancient nations and their culture produced a new South Asia. This paper explores the massive changes that happened to South Asian folk music which creates several ways to correspond to their root and how they are different from each other. After many natural disasters and political changes, South Asian people faced many socio-economic conditions but there was the only way to share their feelings. They articulated their sorrows, happiness, wishes, prayers, and love with music, celebrated social and religious festivals all the way through music. As a result, bunches of folk music are being created with different lyric and tune in every corner of South Asia. -

Family, School and Nation

Family, School and Nation This book recovers the voice of child protagonists across children’s and adult literature in Bengali. It scans literary representations of aberrant child- hood as mediated by the institutions of family and school and the project of nation-building in India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The author discusses ideals of childhood demeanour; locates dissident children who legitimately champion, demand and fight for their rights; examines the child protagonist’s confrontations with parents at home, with teachers at school and their running away from home and school; and inves- tigates the child protagonist’s involvement in social and national causes. Using a comparative framework, the work effectively showcases the child’s growing refusal to comply as a legacy and an innovative departure from analogous portrayals in English literature. It further reviews how such childhood rebellion gets contained and re-assimilated within a predomi- nantly cautious, middle-class, adult worldview. This book will deeply interest researchers and scholars of literature, espe- cially Bengali literature of the renaissance, modern Indian history, cultural studies and sociology. Nivedita Sen is Associate Professor of English literature at Hans Raj College, University of Delhi. Her translated works (from Bengali to English) include Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare Baire ( The Home and the World , 2004) and ‘Madhyabartini’ (‘The In-between Woman’) in The Essential Tagore (ed. Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarty, 2011); Syed Mustafa Siraj’s The Colo- nel Investigates (2004) and Die, Said the Tree and Other Stories (2012); and Tong Ling Express: A Selection of Bangla Stories for Children (2010). She has jointly compiled and edited (with an introduction) Mahasweta Devi: An Anthology of Recent Criticism (2008). -

Similarities of Thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore with Some English Classical Poets

Anudhyan An International Journal of Social Sciences (AIJSS) Similarities of thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore with some English Classical Poets Dr. Tapati Dasgupta Abstract Rabindranath Tagore, who was born in the late half of the 19thcentury was brought up with a cultural heritage which was something novel in the Jorasanko Tagore family of Calcutta. Though Rabindranath did not go in for conventional learning because he had a tremendous dislike for it, he developed profound knowledge on both eastern and western philosophy, science, literature and music by his own initiative and endeavour. Tagore was a man who could blend the ideas of East and West in a perfect harmony. England was all along rich in her literary pursuits and her cultural stage was ornamented with some great poets who can be described as Classical poets.The reign of Queen Elizabeth I is known as the Elizabethan period (1553-1603) in England and in this period poets like William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Milton stood at the pinnacle of fame. The Elizabethan period was followed by the Victorian period, which started with the reign of Queen Victoria and this period lasted from 1837- 1901. The Victorian period was fortunate enough to produce a bunch of well-known romantic poets like Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), P.B. Shelley (1792-1822), William Wordsworth(1770-1850), John Keats (1795-1821), Robert Browning and others. They are much well-known as Romantic poets. Those who directly fell under the Victorian period were William Wordsworth andAlfred Tennyson.Rabindranath, one of the pioneering personalities of Bengal Renaissance had an immense reading of English literature; but he reached the zenith of his fame through his own creative virtues which were purely his own. -

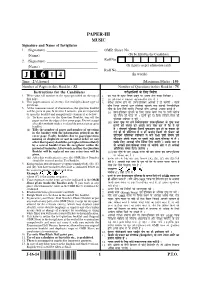

MUSIC Signature and Name of Invigilator 1

PAPER-III MUSIC Signature and Name of Invigilator 1. (Signature) __________________________ OMR Sheet No. : ............................................... (Name) ____________________________ (To be filled by the Candidate) 2. (Signature) __________________________ Roll No. (Name) ____________________________ (In figures as per admission card) Roll No.________________________________ J1 6 1 4 (In words) 1 Time : 2 /2 hours] [Maximum Marks : 150 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 32 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 75 Instructions for the Candidates ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖÙ£ÖµÖÖë Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ×®Ö¤ìü¿Ö 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. ‡ÃÖ ¯Öéšü Ûêú ‰ú¯Ö¸ü ×®ÖµÖŸÖ Ã£ÖÖ®Ö ¯Ö¸ü †¯Ö®ÖÖ ¸üÖê»Ö ®Ö´²Ö¸ü ×»Ö×ÜÖ‹ … this page. 2. ‡ÃÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Ö¡Ö ´Öë ¯Ö“ÖÆü¢Ö¸ü ²ÖÆãü×¾ÖÛú»¯ÖßµÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö Æïü … 2. This paper consists of seventy five multiple-choice type of 3. ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖ ¯ÖÏÖ¸ü´³Ö ÆüÖê®Öê ¯Ö¸ü, ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¤êü ¤üß •ÖÖµÖêÝÖß … ¯ÖÆü»Öê questions. ¯ÖÖÑ“Ö ×´Ö®Ö™ü †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê ŸÖ£ÖÖ ˆÃÖÛúß ×®Ö´®Ö×»Ö×ÜÖŸÖ 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet •ÖÖÑ“Ö Ûêú ×»Ö‹ פüµÖê •ÖÖµÖëÝÖê, וÖÃÖÛúß •ÖÖÑ“Ö †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê †¾Ö¿µÖ Ûú¸ü®Öß Æîü : will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested (i) ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ˆÃÖÛêú Ûú¾Ö¸ü ¯Öê•Ö ¯Ö¸ü »ÖÝÖß ÛúÖÝÖ•Ö to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the Ûúß ÃÖᯙ ÛúÖê ±úÖ›Ìü »Öë … ÜÖã»Öß Æãü‡Ô µÖÖ ×²Ö®ÖÖ Ã™üßÛú¸ü-ÃÖᯙ Ûúß paper seal on the edge of this cover page. -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion.