The Generation of Self Fictions of Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

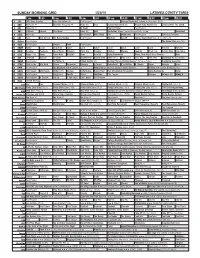

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

87Th Academy Awards Reminder List

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT LAST NIGHT Actors: Kevin Hart. Michael Ealy. Christopher McDonald. Adam Rodriguez. Joe Lo Truglio. Terrell Owens. David Greenman. Bryan Callen. Paul Quinn. James McAndrew. Actresses: Regina Hall. Joy Bryant. Paula Patton. Catherine Shu. Hailey Boyle. Selita Ebanks. Jessica Lu. Krystal Harris. Kristin Slaysman. Tracey Graves. ABUSE OF WEAKNESS Actors: Kool Shen. Christophe Sermet. Ronald Leclercq. Actresses: Isabelle Huppert. Laurence Ursino. ADDICTED Actors: Boris Kodjoe. Tyson Beckford. William Levy. Actresses: Sharon Leal. Tasha Smith. Emayatzy Corinealdi. Kat Graham. AGE OF UPRISING: THE LEGEND OF MICHAEL KOHLHAAS Actors: Mads Mikkelsen. David Kross. Bruno Ganz. Denis Lavant. Paul Bartel. David Bennent. Swann Arlaud. Actresses: Mélusine Mayance. Delphine Chuillot. Roxane Duran. ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY Actors: Steve Carell. Ed Oxenbould. Dylan Minnette. Mekai Matthew Curtis. Lincoln Melcher. Reese Hartwig. Alex Desert. Rizwan Manji. Burn Gorman. Eric Edelstein. Actresses: Jennifer Garner. Kerris Dorsey. Jennifer Coolidge. Megan Mullally. Bella Thorne. Mary Mouser. Sidney Fullmer. Elise Vargas. Zoey Vargas. Toni Trucks. THE AMAZING CATFISH Actors: Alejandro Ramírez-Muñoz. Actresses: Ximena Ayala. Lisa Owen. Sonia Franco. Wendy Guillén. Andrea Baeza. THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Actors: Andrew Garfield. Jamie Foxx. Dane DeHaan. Colm Feore. Paul Giamatti. Campbell Scott. Marton Csokas. Louis Cancelmi. Max Charles. Actresses: Emma Stone. Felicity Jones. Sally Field. Embeth Davidtz. AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY: THE EVOLUTION OF GRACE LEE BOGGS 87th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AMERICAN SNIPER Actors: Bradley Cooper. Luke Grimes. Jake McDorman. Cory Hardrict. Kevin Lacz. Navid Negahban. Keir O'Donnell. Troy Vincent. Brandon Salgado-Telis. -

Trabajo De Fin De Grado

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Jurídicas y de la Comunicación. Grado en Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas. TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO. "Lecciones de comunicación a través de la ficción audiovisual contemporánea mediante la Obra cinematográfica de Jason Ritman.” Presentado por: Juan S. Fernández del Corral. Tutelado por: Alfonso Moral. Segovia, 29 de Mayo de 2016. Índice. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………......…….......1-3 1.1 Objeto de la investigación. Concepto y delimitación 1.2. Tesis: Hipótesis, preguntas y objetivos de la investigación. 1.3. Dificultades y delimitaciones. 2. MARCO TEÓRICO Y ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN…………………..………..4-10 2.1 Biografía del director y justificación de su obra. 2.2 Breve presentación de las obras cinematográficas que componen el objeto a analizar. 1 Gracias por fumar. 2 Up in the air. 3. Men, Women and Children. 2.3. Estado de la cuestión. 3. PRESENTACIÓN Y ANÁLISIS DE LAS LECCIONES COMUNICACIONALES EXTRAIDAS……………...………………………………………………...…….11-41 3.1- Lecciones de Thanks for smoking. 3.2- Lecciones de Up in the air. 3.3- Lecciones de Men, Women & Children. 4. CONCLUSIONES………………………………………………………………….42-49 4.1. Verificación de Hipótesis. Parte 1 Parte 2 4.2. Conclusiones y aportaciones de la investigación. 4.3. Límites y propuesta de nuevas líneas de investigación, posibles aplicaciones de nuestra investigación. 5. BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y FUENTES……………………………………………………50-51 RESUMEN: El presente trabajo trata de ofrecer una visión objetiva de lo que representa una lección de comunicación en el panorama cinematográfico actual . Además de presentar una visión del profesional dedicado a la comunicación según una de las obras del director Jason Reitman. Para ello, es necesario contextualizar la sociedad actual, el impacto de las obras de este director en el panorama cinematográfico contemporáneo y analizar los ejemplos comunicacionales de los fragmentos de su obra que son susceptibles de ser valorados en el trabajo. -

Newsletter 04/15 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 04/15 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 349 - Juni 2015 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 04/15 (Nr. 349) Juni 2015 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Der Juni ist zwar schon fast vorbei, doch wollten wir es uns nicht nehmen lassen, Ihnen noch schnell eine Juni-Ausgabe unseres Newsletters zukommen zu las- sen. Der hätte ja eigentlich schon viel früher produ- ziert werden sollen, doch hat uns der Terminkalender einen kleinen Strich durch die Rechnung gemacht: noch nie standen so viele Kino-Events im Planer wie in den vergangenen Wochen. Will heissen: unsere Videoproduktion läuft auf Hochtouren! Und das ist auch gut so, wollen wir doch schließlich unseren Youtube-Kanal mit Nachschub versorgen. Damit aber nicht genug: inzwischen klopfen verstärkt Kino- betreiber, Filmverleiher und auch DVD-Labels bei uns an, um Videos in Auftrag zu geben. Ein Wunsch, dem wir nur allzu gerne nachkommen – es geht nichts über kreatives Arbeiten! Insbesondere freuen wir uns, dass es wieder einmal eines der beliebtesten Videos in un- serem Youtube-Kanal als Bonus-Material auf eine kommende DVD-Veröffentlichung geschafft hat. Auf persönlichen Wunsch von Regisseur Marcel Wehn wird unser Premierenvideo zu seinem beeindrucken- den Dokumentarfilm EIN HELLS ANGEL UNTER BRÜ- DERN auf der DVD, die Ende Juli veröffentlicht wird, zu finden sein. Merci, Marcel! Übrigens hat genau dieses Video zwischenzeitlich mehr als 26.000 Zugriffe Oben: Hauptdarstellerin Vicky Krieps Rechts: Regisseur Ingo Haeb LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 04/15 (Nr. -

Nominations Announced for the 21St Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------Ceremony Will Be Simulcast Live on Sunday, January 25, 2015 on TNT and TBS at 8 P.M

Nominations Announced for the 21st Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, January 25, 2015 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) Nominees for the 21st Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2014 in five film and eight television categories, as well as the SAG Awards® honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA President Ken Howard introduced Ansel Elgort ("The Fault in Our Stars," "Divergent") and actress/director/producer and SAG Award® recipient Eva Longoria, who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Chair JoBeth Williams and Vice Chair Daryl Anderson announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 21st Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 25, 2015 at 8 p.m. (ET) / 5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT. The SAG Awards® can also be viewed live on the TNT and TBS websites, and also the Watch TNT and Watch TBS apps for iOS or Android (viewers must sign in using their TV service provider user name and password). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the sagawards.tntdrama.com and People.com live Red Carpet Pre-Show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET) / 3 p.m. -

Roof Guilty on All Counts

IN SPORTS: Lakewood boys basketball looking to improve on record season B1 SCIENCE What does a set of 3.7M-year-old footprints reveal? A5 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2016 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents District still trying to understand audit Roof guilty on all counts results, plot course Charleston church shooter could face death penalty BY JEFFREY COLLINS devastating crime in a country stared ahead, much as he did the BY BRUCE MILLS AND MEG KINNARD that was already deeply embroiled entire trial. Family members of [email protected] The Associated Press in racial tension. victims held hands and squeezed The same federal jury that one another’s arms. One woman Sumter School District Superinten- CHARLESTON — Dylann Roof found Roof guilty of all 33 counts nodded her head every time the dent Frank Baker said Thursday he will was convicted Thursday in the will reconvene next month to hear clerk said “guilty.” implement a board member’s recom- chilling slaughter of nine black more testimony and weigh wheth- Roof, 22, told FBI agents he mendation to change the district’s finan- church members who had wel- er to sentence him to death. As cial reporting system immediately, but comed him to their Bible study, a the verdict was read, Roof just SEE ROOF, PAGE A3 he said he still can’t even estimate the year-to-date general fund balance. The change comes after Certified Pub- lic Accountant Robin Poston presented her official audit report Monday night at the board’s scheduled meeting, detailing the school district went more than $6.2 March honors fallen friend million over budget last fiscal year and ended the fiscal year with a fund balance Friends and of $106,449 — a “critically low level” in family of Waltki her opinion. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/26/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/26/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å English Premier League Soccer Prem Goal Zone Action Sports (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore Jack Hanna 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Football Detroit Lions at Atlanta Falcons. (6:30) (N) NFL Sunday Paid Program Motorcycle Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Wrong Turn ›› (2003) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å Healthy Hormones 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Marmaduke › (2010) Owen Wilson, Lee Pace. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 89Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 89TH ACADEMY AWARDS THE ABOLITIONISTS ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS THE MOVIE Actors: Chris Colfer. Actresses: Jennifer Saunders. Joanna Lumley. Julia Sawalha. Jane Horrocks. June Whitfield. Celia Imrie. THE ACCOUNTANT Actors: Ben Affleck. J.K. Simmons. Jon Bernthal. Jeffrey Tambor. John Lithgow. Gary Basaraba. Andy Umberger. Jason Davis. Rob Treveiler. Seth Lee. Actresses: Anna Kendrick. Cynthia Addai-Robinson. Jean Smart. Alison Wright. Mary Kraft. Izzy Fenech. Susan Williams. Sheila Maddox. Kelly Collins Lintz. Viviana Chavez. ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Actors: Johnny Depp. Matt Lucas. Rhys Ifans. Sacha Baron Cohen. Leo Bill. Ed Speleers. Andrew Scott. Richard Armitage. Actresses: Anne Hathaway. Mia Wasikowska. Helena Bonham Carter. Lindsay Duncan. Geraldine James. Hattie Morahan. ALLIED Actors: %UDG3LWW-DUHG+DUULV6LPRQ0F%XUQH\'DQLHO%HWWV0DWWKHZ*RRGH$XJXVW'LHKO7KLHUU\)U«PRQW Vincent Ebrahim. Xavier De Guillebon. Michael McKell. Actresses: Marion Cotillard. Lizzy Caplan. Camille Cottin. Fleur Poad. Miryam Hayward. Iselle Rifat. Aysha Kanayo. Sally Messham. Charlotte Hope. Celeste Dodwell. ALMOST CHRISTMAS Actors: Danny Glover. Romany Malco. JB Smoove. Jessie T. Usher. John Michael Higgins. Omar Epps. Actresses: Mo'Nique. Gabrielle Union. Kimberly Elise. ALWAYS SHINE Actresses: Mackenzie Davis. Caitlin FitzGerald. AMERICAN HONEY Actors: Shia LaBeouf. Actresses: Sasha Lane. Riley Keough. 89th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AMERICAN PASTORAL Actors: Ewan McGregor. Peter Riegert. David Strathairn. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Dakota Fanning. Uzo Aduba. AMERICAN WRESTLER: THE WIZARD Actors: Ali Afshar. George Kosturos. THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE Actors: Jason Sudeikis. Josh Gad. Danny McBride. Keegan-Michael Key. Sean Penn. Tony Hale. Bill Hader. Peter Dinklage. Actresses: Maya Rudolph. Kate McKinnon. ANTHROPOID Actors: Cillian Murphy. -

Production in Ontario 2017

SHOT IN ONTARIO 2017 Feature Films – Theatrical AMERICAN HANGMAN Feature Films – Theatrical Hangman Justice Productions Inc. Producers: Jim Sternberg, Meredith Fowler, Wilson Coneybeare Exec. Producer: Jeff Sackman Director: Wilson Coneybeare Production Manager: Justin Kelly D.O.P.: Mark Irwin Key Cast: Donald Sutherland, Vincent Kartheiser Shooting dates: May 17 - June 12/17 AN AUDIENCE OF CHAIRS Feature Films – Theatrical The Film Works Ltd. Producers: Eric Jordan, Paul Stevens Exec. Producer: n/a Director: Deanne Foley Production Manager: Christine Sola D.O.P.: James Klopko Key Cast: Christopher Jacot, Carolina Bartczak, Peter MacNeill, Daina Barbeau, Edie Inksetter Shooting dates: Aug 2 – Aug 25/17 ANGELIQUE'S ISLE Feature Films – Theatrical Circle Blue Media Inc. Producers: Amos Adetuyi, Dave Clement, Michelle Derosier, Floyd Kane, Elizabeth Guildford Exec. Producer: Rosalie Chilelli Director: Marie-Hélène Cousineau, Michelle Derosier Production Manager: Jeff Coll D.O.P.: Celiana Cárdenas Key Cast: Charlie Carrick, Brendt Thomas Diabo Shooting dates: May 29 - Jun 14/17 BROTHERHOOD Feature Films – Theatrical ROA Productions Inc. Producers: Mehernaz Lentin, Anand Ramayya, Jonathan Bronfman Exec. Producer: n/a Director: Richard Bell Production Manager: Borga Dorter D.O.P.: Adam Swica Key Cast: Brendan Fehr, Dylan Everett, Brendan Fletcher, Spencer Macpherson, Gage Munroe Shooting dates: Sep 18 - Oct 11/17 CLARA Feature Films – Theatrical As of December 31, 2017 1 SHOT IN ONTARIO 2017 Serendipity Point Films Inc. Producer: Gary Lantos Exec. Producer: n/a Director Akash Sherman Production Manager: Lori Fischburg D.O.P.: Nick Haight Key Cast: Troian Bellisario, Patrick J. Adams, Kristen Hager, Ennis Esmer , R.H. Thomson, Jennifer Dales Shooting dates: Mar 6 – Mar 31/17 CODE 8 Feature Films – Theatrical Code 8 Films Inc. -

Interview Zum 30Jährigen Jubiläum Des

18 DEZEMBER 2016 | B 7230 C www.blickpunktf lm.de Nachrichten, Analysen & Trends aus der Filmwirtschaft #51 Verbandsjubiläum Der Erdmann-Triumph Riesending mal Drei Geschäftsaufgabe Der Verband Deutscher Maren Ades Ausnahmef lm RTL-Fiction-Chef Philipp Wie Rainer Heumann die Drehbuchautoren begeht holt sich fünf Preise beim Stef ens über »Winnetou«- Videobranche verlässt und ihr seinen 30. Geburtstag Europäischen Filmpreis an Weihnachten dennoch erhalten bleibt Bitte setzen Sie den Trailer gezielt ein vor ROGUE ONE: A STAR WARS STORY, ASSASSIN’S CREED, PASSENGERS, THE GREAT WALL und xXx – DIE RÜCKKEHR DES XANDER CAGE. Interview DAS DISNEYRoger Crotti -imJAHR großen FILMLAND S A C H S E N - A N H A LT KLAPPT’S. SACHSEN-ANHALT FILMREIF. HIER FEIERN WIR IHRE ERFOLGE! Im Jahr 2016 konnten so viele Filme wie noch nie dem Kinopublikum gezeigt werden, in denen Sachsen-Anhalt steckt: Sei es der Besuchermillionär „Bibi & Tina – Mädchen gegen Jungs“, der Besondere Kinderfilm „ENTE GUT! Mädchen allein zu Haus“, die internationale Koproduktion „Frantz“, der österreichische Oscar®-Beitrag „Vor der Morgenröte“ oder der deutsche Berlinale-Beitrag „24 Wochen“. Am „Drehort Harz“ wurde aktuell „Die kleine Hexe“ gedreht. Der Dreh- und Produktionsstandort Sachsen-Anhalt freut sich auf Ihre Projekte im Jahr 2017! www.medien.sachsen-anhalt.de EDITORIAL 2017 kann kommen enn die Film- alten Recken ihr Pulver noch nicht ver- branche etwas schossen haben. Die Af en machen sich gut kann, dann die Erde endgültig Untertan. Die Schöne ist es, den Blick und das Biest werden als Realf guren für nach vorn zu Disney tanzen. Mr. Grey wird wieder zur richten. -

MANDY LYONS Hair Stylist IATSE 798

MANDY LYONS Hair Stylist IATSE 798 FILM THE GOLDFINCH Department Head Filming Starts January 2018 Director: John Crowley SECOND ACT Department Head Director: Peter Segal A QUIET PLACE Hair Designer to Emily Blunt, John Krassinski, Millicent Simmonds, Noa Jupe Director: John Krasinski SNOWPIERCER Hair Designer to Jennifer Connelly Director: Scott Derrickson THE WEEK OF Department Head Director: Robert Smigel THE ONLY LIVING BOY IN NEW YORK Personal Hair Stylist to Kate Beckinsale Director: Marc Webb KINGSMAN: GOLDEN CIRCLE Personal Hair Stylist to Julianne Moore Director: Matthew Vaughn THE MEYEROWITZ STORIES Department Head Director: Noah Baumbach Cast: Dustin Hoffman, Emma Thompson, Grace Van Patten THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN Personal Hair Stylist to Emily Blunt Director: Tate Taylor GOLD Department Head Director: Stephen Gaghan Cast: Bryce Dallas Howard, Stacy Keach, Toby Kebbell, Corey Stoll, Bruce Greenwood, Bill Camp, Macon Blair, Adam LeFevre NERVE Department Head Director: Henry Joost, Ariel Schulman Cast: Emma Roberts, Dave Franco, Emily Meade, Juliette Lewis FREEHELD Department Head Director: Peter Sollett Cast: Julianne Moore THE MILTON AGENCY Mandy Lyons 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 5 THE INTERN Department Head Director: Nancy Meyers Cast: Rene Russo, Anders Holm, Christina Scherer, Zach Pearlman STILL ALICE Department Head Director: Richard Glatzer, Wash Westmorland Cast: Kristen Stewart; Julianne -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Film Men, Women

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Film Men, Women & Children karya Jason Rietman yang diproduksi oleh Paramount Picture dirilis pada tanggal 17 Oktober 2014 di Amerika. Film ini diangkat dari Novel karya Chad Kultgen dengan judul yang sama. Dengan menggaet beberapa bintang Hollywood seperti Adam Sandler, Jennifer Gardner, Rosemarie DeWitt, Ansel Elgort film ini berhasil meraup keuntungan sebesar $47.553 di Amerika untuk minggu pertama penayangannya dan mendapatkan keuntungan sebesar $461.162 selama penayanganya. Dengan rating 6,7/10 dari 23.335 user imdb (Internet Movie Database). Film Men, Women & Children berdurasi 1 jam 59 menit ini menceritakan dampak dari penggunaan internet terhadap tokoh – tokoh pada film ini yang tanpa mereka sadari mengubah gaya berkomunikasi mereka, cara mereka mencitrakan dirinya di dunia virtual, sampai ke kehidupan asmara mereka. Film ini banyak mengangkat masalah masalah lain yang ditimbulkan oleh internet seperti budaya gamming, anoreksia, berburu popularitas, perselingkuhan hingga maraknya konten vulgar yang sangat mudah di akses melalui internet. Pemutaran perdana film ini dilaksanakan pada tanggal 6 September 2014 di acara Toronto International Film Festival yang selanjutnya disusul dengan penayangan terbatas di berbagai bioskop di dunia pada tanggal 17 Oktober 2014. Beberapa negara yang menayangkan film Men, Women & Children ini adalah Canada, Amerika Serikat, Brazil, UK, Mexico, Australia, beberapa negara di Eropa, Afrika dan Asia. Film ini tidak masuk ke bioskop-bioskop di Indonesia. Penonton di Indonesia hanya bisa menikmati film ini dengan menonton secara online di website streaming film maupun mengunduhnya di internet. Adapun untuk pelanggan UseeTV di Indonesia bisa menikmatinya di channel HBO maupun feature layanan Video On Deman yang disediakan.