The Dead Sea Scrolls: the Present State of Research*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jesus Seminar Revealed �1 of 32

The Jesus Seminar Revealed !1 of !32 By Mark McGee The Jesus Seminar Revealed !2 of !32 The Jesus Seminar Revealed !3 of !32 Part One The Jesus Seminar was a group of “scholars and specialists” interested in renewing “the quest of the historical Jesus.” The name Jesus Seminar would imply that this group had good credentials and would reveal something important about the real life and ministry of the Lord Jesus Christ. That didn’t happen. According to The Jesus Seminar – “Among the findings is that, in the judgment of the Jesus Seminar Fellows, about 18 percent of the sayings and 16 percent of the deeds attributed to Jesus in the gospels are authentic.” Another way of understanding that statement is that 82 percent of the sayings and 84 percent of the deeds attributed to Jesus in the Gospels are NOT authentic. Let that sink in for a minute …. The Jesus Seminar Revealed !4 of !32 The Jesus Seminar would have us believe that the vast majority of what’s written about the sayings and deeds of Jesus Christ in the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) are NOT authentic – not true – never said – never done. Was The Jesus Seminar right? If you’ve read other articles on the FaithandSelfDefense and GraceLife blogs, you know I think The Jesus Seminar was wrong – very wrong. To understand how so-called scholars and specialists reached their conclusions about Jesus and the four Gospels, we need to know a little about how The Jesus Seminar started. It began in Berkeley, California in 1985 as the brain child of Robert W. -

Can the 'Real' Jesus Be Identified with the Historical Jesus? Roland Deines2

Pag Didaskalia-1º Fasc_2009.:Pag Didaskalia-1º Fasc 6/24/09 5:13 PM Page 11 Can the ‘Real’ Jesus be Identified with the Historical Jesus? A Review of the Pope’s Challenge to Biblical Scholarship and the Various Reactions it Provoked1 Roland Deines2 University of Nottingham Introduction: Geza Vermes on Ratzinger’s Jesus In the initial programme for this conference, the present time slot was allocated to Professor Geza Vermes and I deeply regret that he is unable to be with us. His critical reading of the Pope’s book surely would have en- riched our discussion. Knowing Professor Vermes’ work makes it safe to as- sume that his arguments would have focused on the underrated Jewishness 1 In the following paper I focus only on the discussion within German-speaking countries. For a first sum- mary of the discussion in France see F. Nault, ‘Der Jesus der Geschichte: Hat er eine theologische Relevanz?’, in H. Häring (ed.), „Jesus von Nazareth“ in der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion, Berlin: Lit, 2008, pp. 103-21. See now also R. Riesner, ‘Der Papst und die Jesus-Forscher: Notwendige Fragen zwischen Exegese, Dogmatik und Gemeinde’, Theologische Beiträge 39 (2008), pp. 329-345. 2 Parts of this paper have been delivered at the conference ‘The Pope and Jesus of Nazareth’ on 19th and 20th June 2008 at the University of Nottingham. This conference, supported by the British Academy, was the first extended theological discussion on Pope Benedict XVI’s book in the United Kingdom. A shorter version of this version will be published within the conference proceedings: Adrian Pabst and Angus Paddison (eds), The Pope and Jesus of Nazareth, Veritas, London: SCM, 2009. -

Dead Sea Scrolls on the High Street: Popular Perspectives on Ancient Texts"

"Discovering the Dead Sea Scrolls on the High Street: Popular Perspectives on Ancient Texts" by Rev Dr Alistair I. Wilson, Highland Theological College, Dingwall Introduction 1997 marked (almost certainly) the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of the first Dead Sea Scrolls, and so, once again, the significance of these ancient documents is a matter of great public interest. Already, volumes are being published to mark this jubilee in which highly competent scholars discuss questions of a technical nature.1 A recent (May 1998) international conference held at New College, Edinburgh, indicates that academic interest is as strong in Scotland as in the rest of the world. However, it is not only specialists who are interested in the Dead Sea Scrolls (hereafter, DSS). There is widespread public interest in the subject also, and this, in certain respects, is something to be warmly welcomed. This is true simply because of the value of the DSS to archaeology; they have been described as 'the greatest MS [manuscript] discovery of modern times',2 and it is always valuable to be aware of developments in our knowledge of the ancient world. However, the fact that during the 1990s the Dead Sea Scrolls have been at the centre of some of the most startling, dramatic, and controversial events imaginable, leading to massive publicity in both the academic and popular press, has surely added to the public interest in these documents. 1 One of the first of these is the important volume The Scrolls and the Scriptures, edited by S. E. Porter and C. A. Evans (Sheffield: SAP, 1997). -

The Ministry of the Whole People of God in a Mainline Congregation: a Critical Exploration

T The Ministry of the Whole People of God in a Mainline Congregation: A Critical Exploration Norman Maciver Introduction T The primary purpose of this project was to look critically at the story of one ordinary congregation’s experience of ministry and, in so doing, to discover if there are lessons to be learned that will resource its mission in the immediate and long-term future. This cannot be done without a real understanding of the historical, ecclesiastical, cultural and missiological environment in which we have lived and that forms the context of our current challenges. At the same time, we want to hear and pay attention to the perception that others have of our ministry and weave these perceptions into our analysis to be an effective agent of mission in the twenty-first century. My methodology in approaching the project is a praxis-reflection one. This is in the nature of a case study beginning from our own story and, by reflecting on it, discerning the theological issues involved and setting them in the context of our cultural reality and pastoral ministry. What have we in fact been doing and how does a theological study of both the bible and church history impinge on and develop our ministry as that of the ministry of the whole people of God in our situation? In a real sense, by prioritising human experience and following the methods that are central to the biblical ministry and that have been rediscovered in recent years in the South American model of liberation theology, the rich tapestry that evolves from our practice, informed by a biblical theology will, therefore, help us face the resultant new challenge in our practice. -

John and Qumran: Discovery and Interpretation Over Sixty Years Paul N

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 2008 John and Qumran: Discovery and Interpretation over Sixty Years Paul N. Anderson George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Paul N., "John and Qumran: Discovery and Interpretation over Sixty Years" (2008). Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies. 77. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs/77 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Christian Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John and Qumran: discovery and Interpretation over Sixty years Paul N. Anderson It would be no exaggeration to say that the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls was the most signiicant archaeological ind of the twentieth century. As the Jesus movement must be understood in the light of contemporary Judaism, numer- ous comparisons and contrasts with the Qumran community and its writings illumine our understandings of early Christianity and its writings. As our knowl- edge of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls has grown, so have its implications for Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity. Likewise, as understandings of Johannine Christianity and its writings have grown, the Qumran-Johannine analyses have also evolved. he goal of this essay is to survey the scholarly lit- erature featuring comparative investigations of Qumran and the Fourth Gospel, showing developments across six decades and suggesting new venues of inquiry for the future. -

Was Jesus Married?

Summer Fellows Research 2017 WAS JESUS MARRIED? Elizabeth Fleischer 1 Any attempt to separate the historical Jesus of Nazareth from the mythical Jesus Christ is always met with skepticism. There are a fair number of scholars who believe the task to be nearly impossible because almost every written account of Jesus is found in a Gospel.1 It is generally agreed upon that gospels are “testimonies of faith composed by communities of faith and written many years after the events they describe”.2 Thus each account cannot be taken as unbiased historical records but pieces of faith based puzzles which attempt to portray Jesus in a particular fashion. However, countless scholars have developed countless methods to separate the somewhat factual from the purely fictional. By standing on the shoulders of these countless scholarly giants, it becomes increasingly feasible to formulate possible logical answers to fundamental questions about the life of Jesus of Nazareth. For example, was he married? As Christianity has developed, Jesus’s chastity has become increasingly important. The importance of Jesus’s virginal state has become so important that many find any suggestion to the contrary offensive. But without historical accounts definitely written by a contemporary, nothing about Jesus can be stated with certainty. Thus it cannot be unequivocally stated that Jesus was or was not married. The debate over his marital status can only be contrasting possibilities, based upon those accounts which are deemed most accurate and reliable. Apart from the stories of Jesus’s miraculous conception and birth, most written accounts completely omit any mention of Jesus’s adolescence. -

Essene Ethnicity Katherine Schaefers, M.A., University of Leiden Staff, Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, CA, USA

Essene Ethnicity Katherine Schaefers, M.A., University of Leiden Staff, Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, CA, USA Click here to go directly to the Paper. Abstract: Ethnicity is a sociological construct that has immense value if placed within the field of archaeology. By defining the Essenes as an ethnic group, two purposes are served: to provide further evidence that may link the Essenes to the Qumran community, and to display the usefulness of other, less acknowledged concepts for archaeology. In addition, this paper argues for a fluid definition of the Essenes as a solution to discrepancies between the Essenes found in classical literature and the archaeological remains of the Qumran settlement. The tendency to assign the Essenes by default to the Qumran community and whether there are sufficient grounds for this identification is also examined. L’Ethnicité Essénienne Résumé : L’ethnicité est une conception sociologique qui a une grande valeur lorsque située dans le domaine de l’Archéologie. En définissant les Esséniens en tant que groupe ethnique, on satisfait deux objectifs: apporter une preuve supplémentaire qui pourrait relier les Esséniens à la communauté de Qumrân, et démontrer l’utilité d’autres concepts moins reconnus dans l’Archéologie. De plus, cet article supporte une définition fluide des Esséniens comme la solution aux disparités entre les Esséniens de la littérature classique et les restes archéologiques de la colonie de Qumrân. On y examine également la tendance à assigner les Esséniens à la communauté de Qumran par défaut et s’il y a suffisamment de fondement pour faire cette identification. Etnografía Esenia Resumen: La Etnografía es una idea sociológica que tiene inmenso valor si se coloca dentro del campo de la Arqueología. -

Foundations 43

The Dead Sea Scrolls on the High Street Part 2 Alistair Wilson Conspiracies and Cover-ups? Everybody is attracted to an exciting story, not least those working in the media, and this is as true when it comes to the Dead Sea Scrolls as in any other field of interest. Indeed the DSS provide unusually rich ingredients for a drama: accidental discovery, political tensions, secret codes, hidden treasure and more. What more could a journalist ask for? Well, perhaps a religious scandal! The Scandinavian scholar Krister Stendahl writes: It is as a potential threat to Christianity, its claims and its doctrines that the scrolls have caught the imagination of laymen and clergy. 1 Three books in particular have made the headlines in the last few years. Each one is distinctive in its particular slant on the DSS, but they are united in the claim that whatever new evidence they bring to the public requires a complete re-evaluation of historic Christianity. Another characteristic common to each of these volumes is that they have sold in vast numbers and, as the title of this article indicates, are found not simply on the dusty shelves of specialist theological or archaeological bookshops. Rather they sit brightly lit on the shelves of high-street newsagents, in railway stations and in airports. As an illustration of their widespread distribution, the author of this article walked into a second-hand bookshop in Inverness in the Highlands of Scotland (hardly a centre of DSS research!) and found a copy of each of the controversial volumes considered below (indeed, two copies of Eisenman and Wise's book). -

Unitarian Perspectives on Contemporary Religious Thought

Unitarian Perspectives on Contemporary Religious Thought Edited by George D.Chyssides Acknowledgements The editor thanks the Publications Panel of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, who have given great encouragement and made many valuable contributions to the development of this collection of essays. Particular thanks are due to Catherine Robinson for undertaking the onerous task of copy-editing, proof-reading, and preparation of the volume for final production; to Margaret Wilkins for compiling the index; and to Dr Arthur Long for advice and comments on sections of the book. Preface Who are the Unitarians? The Unitarians are a spiritual community who encourage people to think for themselves. They believe • that everyone has the right to seek truth and meaning for themselves; • that the fundamental tools for doing this are one's own life experience, one's reflection upon it, one's intuitive understanding, and the promptings of one's own conscience; • that the best setting for this is a community which welcomes people for who they are, complete with their beliefs, doubts and questions. They can be called religious 'liberals': • 'religious' because they unite to celebrate and affirm values that embrace and reflect a greater reality than self; • 'liberal' because they claim no exclusive revelation or status for themselves; and because they afford respect and toleration to those who follow different paths of faith. They are called 'Unitarians' • because of their traditional insistence on divine unity, the oneness of God; • because they affirm the essential unity of humankind and of creation. History in brief The roots of the Unitarian movement lie principally in the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. -

"Teacher of Righteousness and the Messiah in the Damascus

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGY THE TEACHER OF RIGHTEOUSNESS AND THE MESSIAH IN THE DAMASCUS DOCUMENT BARBARA THIERING, University of Sydney The re-issue of Schechter's 1910 publication of the Zadokite Work! reminds us that there are certain controversial passages in this document, concerning the identity of the Teacher of Righteous ness with the Messiah. Schechter's original translation supported the view that the two were one and the same. It would be worth while looking at subsequent treatments of the relevant passages in translations that have appeared since the discovery of fragments of the same work among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Schechter published a transcription and translation of two manuscripts, A and B, found in the Cairo Genizah. A is dated 10th cent. A.D., B in the 12th cent. Schechter was criticizea severely by R. H. Charles for withholding the manuscripts from other scholars, and for the careless nature of his work. Fragments of the same document came to· light in Cave IV at Qumran. It became clear that it and the other sectarian writings were closely related, although possibly representing different stages in the development of the Qumran sect. The new fragments were sufficient to indicate an altered order of the columns, but transla tions still depend on the Cairo MSS, photographs of which were published by Zeitlin in 1952.2 The work is now usually called the Damascus Document. The controversial passages are 2:12, 5:21-6:1, 7:19, 6:11, 8:13-15, 20:1 (= 8:23). 2: 12 reads: wayyodiCem beyad mesiho ruah qodso. -

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and Its Implications For

“The Centrality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and its Implications for Missions in a Multicultural Society” INTRODUCTION: Christianity stands or falls with the bodily resurrection of Jesus. The apostle Paul certainly understood this to be the case. In that great resurrection chapter, 1 Cor. 15, Paul says, “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is without foundation, and so is your faith. In addition, we are found to be false witnesses about God, because we have testified about God that He raised up Christ – whom He did not raise up… And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is worthless; you are still in your sins” (vs. 14-15, 17). Henry Thiessen agrees with the apostle when he writes: It [the resurrection] is the fundamental doctrine of Christianity. Many admit the necessity of the death of Christ who deny the importance of the bodily resurrection of Christ. But that Christ’s physical resurrection is vitally important is evident from the fundamental connection of this doctrine with Christianity. In 1 Cor. 15:12-19 Paul shows that everything stands or falls with Christ’s bodily resurrection: apostolic preaching is vain (v. 14), the apostles are false witnesses (v. 15), the Corinthians are yet in their sins (v.17), those fallen asleep in Christ have perished (v. 18), and Christians are of all men most miserable (v. 19), if Christ has not risen.1 It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain the birth of the church and its gospel message apart from the resurrection of Jesus. The whole of New Testament faith and teaching orbits about the confession and conviction that the crucified Jesus is the Son of God established and vindicated as such “by the resurrection from the dead according to the Spirit of holiness” (Rom. -

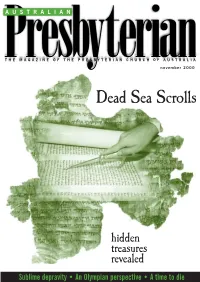

Dead Sea Scrolls

november 2000 Dead Sea Scrolls hidden treasures revealed Sublime depravity • An Olympian perspective • A time to die Are you ready to develop as Do you know young Christian a Christian leader? leaders who you want to sup- 21C is a leadership development conference which will encourage young Christians in leadership, and inspire and equip them for gospel ministry. It is aimed at young lead- ers (aged 18-28) in the Presbyterian church, not only those interested in full-time Get more information or an application form at www.go.to/21c or email us at [email protected] or contact John McClean on (02) 6342 1467 PO Box 296 Cowra NSW 2794 SCHOOL OF CHRISTIAN STUDIES THEOLOGY Advanced Diploma/Diploma/Certificate IV ■ Quality evangelical theological education ■ Lecturers with broad ministry experience ■ ACT Accredited, Austudy available, Mature Age entry ■ Train for ministry or study for interest at ROBERT MENZIES COLLEGE MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY, NORTH RYDE Contact us for a Prospectus Ph: (02) 9936 6020 Fax: (02) 9936 6032 Email: [email protected] November 2000 No. 521 EDITORIAL OLYMPICS Evidence for the defence . 4 An Olympian view . 22 An event is coming that will make Sydney’s success insignificant, DEAD SEA SCROLLS reports John Woods. The dawn of Christianity . 5 The scrolls enrich our context for the early church, reports Bernard PARENTING Secombe. Scrolls and Scripture. 7 The disillusioned generation. 23 John Davies talks to Peter Hastie about the scrolls and the Bible. Ecclesiastes speaks as cogently today as ever, sugests Marion Andrews. Conspiracy theory. 9 Adrian Schepl finds little to fear in Barbara Thiering’s bizarre challenge to orthodoxy.