Word-Is-Out.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meet Pioneer of Gay Rights, Harry Hay

Meet Pioneer of Gay Rights, Harry Hay His should be a household name. by Anne-Marie Cusac August 9, 2016 Harry Hay is the founder of gay liberation. This lovely interview with Hay by Anne-Marie Cusac was published in the September 1998 issue of The Progressive magazine. Then-editor Matt Rothschild called Hay "a hero of ours," writing that he should be a household name. He wrote: "This courageous and visionary man launched the modern gay-rights movement even in the teeth of McCarthyism." In 1950 Hay started the first modern gay-rights organization, the underground Mattachine Society, which took its name from a dance performed by masked, unmarried peasant men in Renaissance France, often to protest oppressive landlords. According to Hay's 1996 book, Radically Gay, the performances of these fraternities satirized religious and political power. Harry Hay was one of the first to insist that lesbians and gay men deserve equality. And he placed their fight in the context of a wider political movement. "In order to earn for ourselves any place in the sun, we must with perseverance and self-discipline work collectively . for the first-class citizenship of Minorities everywhere, including ourselves," he wrote in 1950. At first, Hay could not find anyone who would join him in forming a political organization for homosexuals. He spent two years searching among the gay men he knew in Los Angeles. Although some expressed interest in a group, all were too fearful to join a gay organization that had only one member. But drawing on his years as a labor organizer, Hay persisted. -

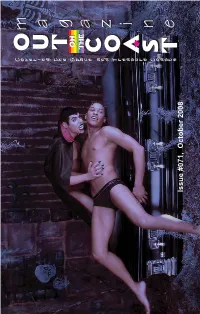

C O a S T O Ut

C o v e OOm r i n g U U a t h e TT S ON g p a THE c e a a n CC d T z r O e O a s u i r AA e C n o S n a S s t s e Issue #071, October 2008 TT 4060 W. New Haven Out on the Coast magazine INSIDE Melbourne, FL published by OOTC Publishing, Inc. PO Box 155, Roseland, FL 32957 (321) 724-1510 Horoscope .......................................... 772.913.3008 Jacqueline www.myspace.com/coldkegnightclub [email protected] publisher/editor Tea Time ..............................................10 Miss T www.coldkegnightclub.com Lee A. Newell II [email protected] Spiritually Speaking .......................12 Rev. Dr. Jerry Seay contributing writers Rev. Dr. Jerry L. Seay In My Words ......................................18 Lexi Wright Rev. Gregory L. Denton. Oct 31 & Nov 1 Miss T Member Maps ...............................................1 - 17 photographers In the New s ...................................22 Ghouls Curse of Richard Cases Directory ..............................28 - 29 account executives Dan Hall 772-626-1682 Subscription information: $24 for 12 issues. Gone Wild The Keg Subscribe on-line at: OOTCmag.com or send [email protected] your check or money order to: Out on the Coast Shane Combs 321-557-2193 magazine, PO Box 155, Roseland, FL 32957-0155 with with [email protected] Issues mailed First Class in plain envelope. Wesley Strickland 321-626-5308 Tasha Scott Velvet LeNore [email protected] Charles Sullivan 321-914-4021 & Roz Russell & Company [email protected] national advertising representative st Rivendell Media Company Costume contest both nights with 1 & 1248 Rt. -

Hay, Harry (1912-2002) by Linda Rapp

Hay, Harry (1912-2002) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. A portrait of Harry Hay by Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Stathis Orphanos. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Courtesy Stathis Orphanos.Image Activist Harry Hay is recognized as one of the principal founders of the gay liberation copyright © Stathis movement in the United States. An original member of both the Mattachine Society Orphanos.All Rights Reserved. and the Radical Faeries, he devoted his life to the cause of equality and dignity for glbtq people. Early Life and Education Hay's parents, both American, met and married in South Africa, where his father Henry Hay, known as Big Harry, was a manager in Cecil Rhodes' mining company. When the birth of their first child was impending, Margaret Neall Hay sailed for England, where their son Henry, Jr., called Little Harry, was born on April 7, 1912 in Worthington, Sussex. The senior Hay saw little of his family for the next two years, but when World War I broke out, he sent for them to join him in Chile, where he had another mining job. After suffering a serious injury on a work site, Hay resettled the family in California. "Big Harry" Hay was harsh, opinionated, demanding, and quick to criticize anything that he perceived as less than perfect in his elder son, from insufficient "manliness" to his grades in school. In later years Hay spoke of his determination to live a life completely different from his father's because of his "personal hatred" for the man. Hay stated that he was aware--however indistinctly at first--of his sexual orientation at a very early age. -

LGBTQ Timeline

Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Re-Learning Consent from Our ForeQueers Timeline 1917: Individuals considered to be “psychopathically inferior,” including LGBT people, are banned from entering the US. 1921: US Naval report on entrapment of “perverts” within its ranks. In 1943, the US military officially bans gays and lesbians from serving in the Armed Forces. 1924: The Society for Human Rights, an American homosexual rights organization founded by Henry Gerber, is established in Chicago. It is the first recognized gay rights organization in the US. A few months after being chartered, the group ceased to exist in the wake of the arrest of several of the Society's members. 1935: “Successful” electric shock therapy treatment of homosexuality is reported at American Psychological Association meeting. 1950: The Mattachine Society, founded by Harry Hay and a group of Los Angeles male friends, is formed to protect and improve the rights of homosexuals. 1955: The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first lesbian rights organization in the US, forms in San Francisco. It is conceived as a social alternative to lesbian bars, which were considered illegal and thus subject to raids and police harassment. It lasted for fourteen years and became a tool of education for lesbians, gay men, researchers, and mental health professionals. As the DOB gained members, their focus shifted to providing support to women who were afraid to come out, by educating them about their rights and gay history. 1963: Gay man, African-American civil rights and nonviolent movement leader Bayard Rustin is the chief organizer of the March on Washington. -

Curriculum & Action Guide

DVD TITLE VISIONARIESVISIONARIESFacilitating a Discussion &Finding aVICTORIES Facilitator IdentifyEARLY LEADERSyour own. WhenIN THE the LGBT 90’s MOVEMENT hit, all the Identify your own. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was &easier and more.VICTORIESeasier and more. Be knowledgeable. When the 90’s hit, all the Be knowledgeable. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was easier and more. easier and more. Be clear about your role. When the 90’s hit, Be clear about your role. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies all the new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate offered people a new way to communicate VISIONARIESthat was easier and more. that was easier and more. Know your group. When the 90’s hit, all the Know your group. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was easier and more. easier and more. NO SECRET ANYMORE: THE TIMES HOPE ALONG THE WIND: THE LIFE OF DEL MARTIN & PHYLLIS LYON OF HARRY HAY & VICTORIESa film by JEB (Joan E. Biren) a film by Eric Slade Curriculum Guide VISIONARIESwww.frameline.org/distribution 1 TABLE OF CONT VISIONARIES & VICTORIES Table of Contents FILM SYNOPSES : : : : : : : : : : 3 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE : : : 5 CLASSROOM CURRICULUM : : : 8 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS : : : 11 RESOURCES : : : : : : : : 12 VOCABULARY : : : : : : : 14 TIMELINE : : : : : : : : 16 photo credits: WORKSHEETS : : : : : : : 20 Lyon & Martin: unknown; Hay: Mark Thompson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS : : : : 22 Youth In Motion is funded in part through the generous support of the James Irvine Foundation and the Bob Ross Foundation. -

Peter Adair Papers, 1973-1986GLC 70

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8z60rc9 No online items Finding Aid to the Peter Adair Papers, 1973-1986GLC 70 Finding aid prepared by Tim Wilson James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] February 2010 Finding Aid to the Peter Adair GLC 70 1 Papers, 1973-1986GLC 70 Title: Peter Adair Papers, Date (inclusive): 1973-1986 Date (bulk): 1974-1979 Collection Identifier: GLC 70 Creator: Adair, Peter, 1944-1996 Physical Description: 79 cubic foot boxes, 31 boxes of various sizes (max. 16-inches x 16-inches x 3-inches)(110.0 cubic feet) Contributing Institution: James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] Abstract: The bulk of the collection centers on the documentary film Word Is Out: stories of some of our lives (1977), a ground-breaking exploration of the lives of 26 gay men and women. A small portion of the collection concerns The AIDS Show: artists involved with death and survival (1986), a production of Peter Adair and Rob Epstein's with Theatre Rhinoceros. Physical Location: The majority of the collection is stored onsite. Boxes 23, 27, 29/1, 29/2, 40, and 45-54 are stored at UCLA. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Access The collection is available for use during San Francisco History Center hours, with photographs available during Photo Desk hours. Significant portions of the original film and sound footage found in Series 3 were restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archives, and are still maintained there. -

Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers

Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Guide to the ONE Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Grant #PW-50526-10 2010-2012 Project Guide by Greg Williams ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90007 213.821.2771 [email protected] one.usc.edu © July 2012 ONE Archives at the USC Libraries Director’s Note In October 1952, a small group began meeting to discuss the possible publication and distribution of a magazine by and for the “homophile” community. The group met in secret, and the members knew each other by pseudonyms or first names only. An unidentified lawyer was consulted by the members to provide legal advice on creating such a publication. By January 1953, they created ONE Magazine with the tagline “a homosexual viewpoint.” It was the first national LGBTQ magazine to openly discuss sexual and gender diversity, and it was a flashpoint for all those LGBTQ individuals who didn’t have a community to call their own. ONE has survived a number of major changes in the 60 years since those first meetings. It was a publisher, a social service organization, and a research and educational institute; it was the target of major thefts, FBI investigations, and U.S. Postal Service confiscations; it was on the losing side of a real estate battle and on the winning side of a Supreme Court case; and on a number of occasions, it was on the verge of shuttering… only to begin anew. -

Container Listing

Harry Hay Papers GLC 44 1 San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library CONTAINER LISTING Series I. Personal & Biographical Materials, 1911-1991 Container Folder Folder Title Date Box 1 1 Hay Genealogy 1911-1987 2 Vital/Baptismal Records 1912 3 School Notebook (Los Angeles High thru Stanford) 1928-1932 4 Los Angeles High School Yearbook, 1929 1929 5 Materials related to Stanford 1929-1931 6 Linoleum Block prints, 1934-1937 1934-1937 7 Linoleum Block, 1937 (n.b.: REALIA?) 1937 8 Materials related to Communist Party affiliation 1945-1947 9 Materials related to the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) 1955-1991 10 Biographical Materials n.d. 11 Archival Sources n.d. 12 Awards 1981-1999 13 Memorials 1982-1998 14 RFC: An Oral History (1 of 2) 1986 15 RFC: An Oral History (2 of 2) 1986 16 RFC: Oral History Correspondence 1989 17 Harry Hay’s edits of RFC 1989 18 Book Review: The Trouble With Harry Hay 1990 19 Harry Hay’s FBI file (1 of 2) 1991 20 Harry Hay’s FBI file (2 of 2) 1991 21 Transcript: Interview with Lance Bowling & Catherine Smith 1992 22 Personal Reminiscences 1993-1998 23 Transcript: Interview with Randy Wicker & Jim Kepner 1996 Box 2 1 Radically Gay Book Signing Tour 1996 Series II. Materials Related to the Mattachine Society, 1948-1964 Container Folder Folder Title Date Box 2 2 Articles: Les Mattachines n.d. 3 Mattachine Questionnaires n.d. 4 [Administrative Chart] 1950 5 Int’l Bachelors Fraternal Orders for Peace & Social Dignity (Bachelor’s Anonymous) 1950 6 Discussion Group Topics (typed) 1951 7 Membership Pledge 1951 8 Mission Statements 1951 9 Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment 1952 10 Rudi Gernreich’s Mattachine Notebook, 1952 1952 11 Mattachine Foundation 1952-1956 Harry Hay Papers GLC 44 2 San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library Series II. -

Osmond-Williams, Philippa (2019) Changing Scotland: a Social History of Love in the Life and Work of Edwin Morgan

Osmond-Williams, Philippa (2019) Changing Scotland: A social history of love in the life and work of Edwin Morgan. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/75142/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Changing Scotland: A Social History of Love in the Life and Work of Edwin Morgan Philippa Osmond-Williams M.A. (Hons), M.Phil. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) Department of Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2019 Abstract Examining love in the life and work of Edwin Morgan (1920-2010), this thesis argues that Morgan’s literary and artistic demonstrations of love inherently respond to the legal, political, and social changes of Scotland in the twentieth and twenty-first century. By mapping Morgan’s biographical contexts within Scotland’s wider social history and culture, the impact of the nation and its shifting attitudes on Morgan’s collected works is delineated. An examination of material only available to researchers, including Morgan’s correspondence and scrapbooks held in Archives and Special Collections at Glasgow University Library, supplements this comprehensive exploration of the significance of love in Morgan’s life and work. -

A History of Queer New Mexico, 1920S-1980S Jordan Biro

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-1-2015 Uncommon Knowledge: A History of Queer New Mexico, 1920s-1980s Jordan Biro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Biro, Jordan. "Uncommon Knowledge: A History of Queer New Mexico, 1920s-1980s." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ hist_etds/8 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jordan Biro Walters Candidate HISTORY Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Virginia Scharff, Chairperson Cathleen Cahill Andrew K. Sandoval-Strausz Peter Boag UNCOMMON KNOWLEDGE: A HISTORY OF QUEER NEW MEXICO, 1920S-1980S BY JORDAN BIRO WALTERS B.A., History, California State University Sacramento, 2004 M.A., Public History, California State University, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2015 ©2015, Jordan Biro Walters iii DEDICATION For my husband, David. May we always share the quest for knowledge together. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I thank all of the oral history participants from whom I’ve learned. Their narratives have given clarity of purpose to this project. The participants whom I interviewed include, Ginger Chapman, Vangie Chavez, Therese Councilor, Ronald Dongahe, Jean Effron, Zonnie Gorman, Bennett A. -

History of the Faeries (Including: Murray Edelman, Joey Cain, and Agnes De Garron) January 15Th 2012

1 History of the Faeries (including: Murray Edelman, Joey Cain, and Agnes de Garron) January 15th 2012 http://vimeo.com/35171786 Recorded by: Peter "speck" Lien ([email protected]) Transcribed by: Husk (Michael James Lecker) ([email protected]) Summary: Joey Cain, Murray Edelman and Agnes de Garron pass down their understanding of early faerie beginnings – personally and generally. Before the Sirst gathering, The “First Gathering” and discussed the role Harry Hay played in the formation of the Radical Faeries as well as feedback and discussion from many faeries present at this circle – held at the William Way LGBT Center on January 15th 2012 during the Philadelphia Faerie MLK Gatherette. Body: Joey Cain: “My name is Joey Cain and I live in San Francisco. I have been involved with the faeries since about 1980 and was very involved with Harry Hay and John Burnside in their care in San Francisco. I was part of the group that moved them up from LA and took care of them in the last ten years of their lives. I have been researching not just Radical Faerie history, but what I call the roots of the Radical Faeries, which implies that there is a set of values that we share as Radical Faeries and there is an actual historical precedent for those values as gay men have come from. So part of my larger project is starting with Walt Whitman, who I do see as the sort of inventor of not just modern gay male consciousness, but I think of a particular way of men viewing themselves. -

The Influence of the United Daughters of the Confederacy on Southern United States History and Memorialization

Of Plantations and Monuments: The Influence of the United Daughters of the Confederacy on Southern United States History and Memorialization By Amanda Chrestensen A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY-MUSEUM STUDIES University of Central Oklahoma Fall 2018 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank the Chair of my Committee Heidi Vaughn. I have never met a person with so much patience and kindness. Thank you for all the emails you sent me with new resources and mental health information. I am not sure I would have been as successful with any other advisor. I am beyond grateful for the years we have worked together. My parents are my biggest supporters. I would not be here today turning this thesis in without all their love and support. Thank you to my boss and friend Lisa Hopper for understanding school is my priority and for consistently letting me take time off work for the last two years to “finish” my thesis. Shout out to my thesis buddy Matt Berry. Congratulations on successfully defending your dissertation and earning your Ph.D. Thank you to the people who read draft of my work and responded with helpful insight, Joshua Stone, Carrie Atkins, and Dr. Huneke. Thank you to my fellow peers and my friends for always providing me with words of encouragement when I faced self-doubt. I must admit, I was not sure I would make it to this point. So thank you to everyone! I Abstract This thesis evaluates the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s (UDC) interpretation of Southern history through the mediums of textbooks, youth groups, and Confederate monuments in public spaces and how this interpretation affects the way historical plantations present antebellum history today in Louisiana.