University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday 15 October 11:00 an Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma!

Thursday 15 October 11:00 An Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma! Please allow 10 minutes for introductions Friday 16 October before all films during Widescreen Weekend. 09.45 Interstellar: Visual Effects for 70mm Filmmaking + Interstellar Intermissions are approximately 15 minutes. 14.45 BKSTS Widescreen Student Film of The Year IMAX SCREENINGS: See Picturehouse 17.00 Holiday In Spain (aka Scent of Mystery) listings for films and screening times in 19.45 Fiddler On The Roof the Museum’s newly refurbished digital IMAX cinema. Saturday 17 October 09.50 A Bridge Too Far 14:30 Screen Talk: Leslie Caron + Gigi 19:30 How The West Was Won Sunday 18 October 09.30 The Best of Cinerama 12.30 Widescreen Aesthetics And New Wave Cinema 14:50 Cineramacana and Todd-AO National Media Museum Pictureville, Bradford, West Yorkshire. BD1 1NQ 18.00 Keynote Speech: Douglas Trumbull – The State of Cinema www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/widescreen-weekend 20.00 2001: A Space Odyssey Picturehouse Box Office 0871 902 5756 (calls charged at 13p per minute + your provider’s access charge) 20.00 The Making of The Magnificent Seven with Brian Hannan plus book signing and The Magnificent Seven (Cubby Broccoli) Facebook: widescreenweekend Twitter: @widescreenwknd All screenings and events in Pictureville Cinema unless otherwise stated Widescreen Weekend Since its inception, cinema has been exploring, challenging and Tickets expanding technological boundaries in its continuous quest to provide Tickets for individual screenings and events the most immersive, engaging and entertaining spectacle possible. can be purchased from the Picturehouse box office at the National Media Museum or by We are privileged to have an unrivalled collection of ground-breaking phoning 0871 902 5756. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

History of Widescreen Aspect Ratios

HISTORY OF WIDESCREEN ASPECT RATIOS ACADEMY FRAME In 1889 Thomas Edison developed an early type of projector called a Kinetograph, which used 35mm film with four perforations on each side. The frame area was an inch wide and three quarters of an inch high, producing a ratio of 1.37:1. 1932 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences made the Academy Ratio the standard Ratio, and was used in cinemas until 1953 when Paramount Pictures released Shane, produced with a Ratio of 1.66:1 on 35mm film. TELEVISION FRAME The standard analogue television screen ratio today is 1.33:1. The Aspect Ratio is the relationship between the width and height. A Ratio of 1.33:1 or 4:3 means that for every 4 units wide it is 3 units high (4 / 3 = 1.33). In the 1950s, Hollywood's attempt to lure people away from their television sets and back into cinemas led to a battle of screen sizes. Fred CINERAMA Waller of Paramount's Special Effects Department developed a large screen system called Cinerama, which utilised three cameras to record a single image. Three electronically synchronised projectors were used to project an image on a huge screen curved at an angle of 165 degrees, producing an aspect ratio of 2.8:1. This Is Cinerama was the first Cinerama film released in 1952 and was a thrilling travelogue which featured a roller-coaster ride. See Film Formats. In 1956 Metro Goldwyn Mayer was planning a CAMERA 65 ULTRA PANAVISION massive remake of their 1926 silent classic Ben Hur. -

Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground

Introduction Nicholas Ray and the Potential of Cinema Culture STEVEN RYBIN AND WILL SCHEIBEL THE DIRECTOR OF CLASSIC FILMS SUCH AS They Live by Night, In a Lonely Place, Johnny Guitar, Rebel Without a Cause, and Bigger Than Life, among others, Nicholas Ray was the “cause célèbre of the auteur theory,” as critic Andrew Sarris once put it (107).1 But unlike his senior colleagues in Hollywood such as Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks, he remained a director at the margins of the American studio system. So too has he remained at the margins of academic film scholarship. Many fine schol‑ arly works on Ray, of course, have been published, ranging from Geoff Andrew’s important auteur study The Films of Nicholas Ray: The Poet of Nightfall and Bernard Eisenschitz’s authoritative biography Nicholas Ray: An American Journey (both first published in English in 1991 and 1993, respectively) to books on individual films by Ray, such as Dana Polan’s 1993 monograph on In a Lonely Place and J. David Slocum’s 2005 col‑ lection of essays on Rebel Without a Cause. In 2011, the year of his centennial, the restoration of his final film,We Can’t Go Home Again, by his widow and collaborator Susan Ray, signaled renewed interest in the director, as did the publication of a new biography, Nicholas Ray: The Glorious Failure of an American Director, by Patrick McGilligan. Yet what Nicholas Ray’s films tell us about Classical Hollywood cinema, what it was and will continue to be, is far from certain. 1 © 2014 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel After all, what most powerfully characterizes Ray’s films is not only what they are—products both of Hollywood’s studio and genre systems—but also what they might be. -

Pictures Afraid You Have Your Dalys Mixed Up

What's New SUSAN HAYWARD from Coast to Coast exciting (Continued from page 10) really sisters. Their ages are: Christine, 25, Dorothy, 23, and Phyllis, 22.... Miss A. Y., Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Johnny Des- mond is on a two -month leave of absence new from the Breakfast Club program, so he can make personal appearances. He is due back on the show October 23.... Miss J. F., San Antonio, Texas: Yes, John Daly is married, and has been for many years. I'm pictures afraid you have your Dalys mixed up. In- JEFF HUNTER cidentally, John recently signed a long- term contract with the American Broad- casting Company as a vice -president in of charge of news. He will continue to be Off-Guard Candids Your the emcee on What's My Line? however. To all of the readers who wrote about Frank Dane, who played Knap Drewer on Favorite Movie Stars the Hawkins Falls show: Frank is no longer on the program because the part of Drewer is no longer in the script. Knap chartered All the selective skill of our ace a private plane to fly from London to the * Isle of Man, in the story, and was killed cameramen went into the making when the plane crashed into the Irish of these startling, 4 x 5, quality DORIS DAY Sea. glossy prints. What ever Happened To . ? John Beal, the movie actor, who used to appear on the Freedom Rings TV show? Since leaving this show, John hasn't been * New poses and names are con- on any regular program, but has been stantly added. -

El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses

9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 75 Chapter 2 The Passion of El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses I started with the final scene. This lifeless knight who is strapped into the saddle of his horse ...it’s an inspirational scene. The film flowed from this source. —Anthony Mann, “Conversation with Anthony Man,” Framework 15/16/27 (Summer 1981), 191 In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. —Karl Marx, Capital, 165 It is precisely visions of the frenzy of destruction, in which all earthly things col- lapse into a heap of ruins, which reveal the limit set upon allegorical contempla- tion, rather than its ideal quality. The bleak confusion of Golgotha, which can be recognized as the schema underlying the engravings and descriptions of the [Baroque] period, is not just a symbol of the desolation of human existence. In it transitoriness is not signified or allegorically represented, so much as, in its own significance, displayed as allegory. As the allegory of resurrection. —Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, 232 The allegorical form appears purely mechanical, an abstraction whose original meaning is even more devoid of substance than its “phantom proxy” the allegor- ical representative; it is an immaterial shape that represents a sheer phantom devoid of shape and substance. —Paul de Man, Blindness and Insight, 191–92 Destiny Rides Again The medieval film epic El Cid is widely regarded as a liberal film about the Cold War, in favor of détente, and in support of civil rights and racial 9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 76 76 Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media equality in the United States.2 This reading of the film depends on binary oppositions between good and bad Arabs, and good and bad kings, with El Cid as a bourgeois male subject who puts common good above duty. -

Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 the FAN - Ed Bianchi

Domingo 9 17:00 THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD - Martin Ritt 19:00 PROVIDENCE - Alain Resnais 21:00 THE FAN - Ed Bianchi Lunes 10 CGAC 17:00 L’AVEU - Constantin Costa-Gavras 19:30 L’AMOUR À MORT - Alain Resnais 21:15 THE RAIN PEOPLE - Francis Ford Coppola Martes 11 17:00 A DANDY IN ASPIC - Anthony Mann, Laurence Harvey 19:00 THE DEADLY AFFAIR - Sidney Lumet 21:00 DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN - Wim Wenders Miércoles 12 16:30 SECHSE KOMMEN DURCH DIE WELT - Rainer Simon 18:00 TILL EULENSPIEGEL - Rainer Simon 19:45 JADUP UND BOEL - Rainer Simon 21:30 DIE FRAU UND DER FREMDE - Rainer Simon Jueves 13 17:45 WENGLER & SÖHNE, EINE LEGENDE - Rainer Simon 19:30 DER FALL Ö - Rainer Simon 21:15 WORK IN PROGRESS: CORTOMETRAJES DE MARCOS NINE - Marcos Nine Viernes 14 16:00 FÜNF PATRONENHÜLSEN - Frank Beyer 17:30 NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN - Frank Beyer 19:45 KARBID UND SAUERAMPFER - Frank Beyer 21:15 JAKOB, DER LÜGNER - Frank Beyer 23:00 DER VERDACHT - Frank Beyer Miércoles 19 21:30 DER TUNNEL - Roland Suso Richter Jueves 20 16:00 CARLOS - Olivier Assayas 21:45 DIE STILLE NACH DEM SCHUSS - Volker Schlöndorff Venres 21 16:00 8MM-KO ERREPIDEA - Tximino Kolektiv (Ander Parody, Pablo Maraví, Itxaso Koto, Mikel Armendáriz) 17:00 PROXECTO NIMBOS (SELECCIÓN DE CORTOMETRAJES) - Varios autores 17:45 WORK IN PROGRESS: O LUGAR DOS AVÓS - Víctor Hugo Seoane 20:15 EL CORRAL Y EL VIENTO - Miguel Hilari 21:15 OUROBOROS - Carlos Rivero, Alonso Valbuena Sábado 22 17:00 VIDEOCREACIÓNS - Olalla Castro 18:30 A HISTÓRIA DE UM ERRO - Joana Barros 20:15 TRUE ROMANCE. -

Marilyn Monroe, Lived in the Rear Unit at 5258 Hermitage Avenue from April 1944 to the Summer of 1945

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2179-HCM ENV-2015-2180-CE HEARING DATE: June 18, 2015 Location: 5258 N. Hermitage Avenue TIME: 10:30 AM Council District: 2 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: North Hollywood – Valley Village 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: South Valley Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Valley Village 90012 Legal Description: TR 9237, Block None, Lot 39 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the DOUGHERTY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Hermitage Enterprises LLC c/o Joe Salem 20555 Superior Street Chatsworth, CA 91311 APPLICANT: Friends of Norma Jean 12234 Chandler Blvd. #7 Valley Village, CA 91607 Charles J. Fisher 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. NOT take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2179-HCM 5258 N. Hermitage, Dougherty House Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The corner property at 5258 Hermitage is comprised of two one-story buildings. -

Aster of Suspense: Alfred Hitchcock

Visual arts example A IB DIPLOMA- VISUAL ARTS EXTENDED ESSAY aster of Suspense: Alfred Hitchcock How does Alfred Hitchcock visually guide viewers as he creates suspense in films such as ''The Pleasure Garden,''''The Lodger,'' ''Strangers on a Train'' and 'Psycho''? Candidate Number: Word Count: 3780 IMAGES: Please note that until copyright has been confirmed, all images have been removed. Apologies for the inconvenience. Extended essay 1 Visual arts example A IB VISUAL ARTS - EXTENDED ESSAY Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 3 THE BEGINNING OF FILM .................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK ......................................................................... 5 EARLY SILENT FILMS ............................................................................................................ 6 THE AMERICAN FILMS FROM THE 1950s ONWARDS ................................................... 11 Strangers on a Train (1951) .............................................................................................................. 11 Pyscho (1963) .................................................................................................................................... 13 INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARYFILMS ...................................................................... 17 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

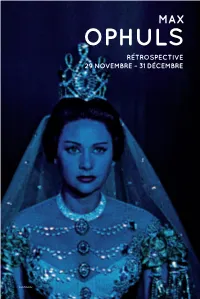

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux.