Harley Gillman (HG), 611 East 1600 North, Orem, Utah 84097 Interviewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2013 Issue

JULY 2013 cycling utah.com 1 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 5 FREE JULY 2013 cycling utah 2013 UTAH, IDAHO, & WESTERN EVENT CALENDAR INSIDE! ROAD MOUNTAIN TRIATHLON TOURING RACING COMMUTING MOUNTAIN WEST CYCLING MAGAZINE WEST CYCLING MOUNTAIN ADVOCACY 2 cycling utah.com JULY 2013 SPEAKING OF SPOKES It’s July! Tour Time! The Tour. Once again, July is fast have already sounded and The Tour World Championships, I check the By David Ward approaching and the Tour de France will be under way. results daily to keep up on the racing will begin rolling through the flatlands, I am a fan of bike racing, and love scene. Sometimes, like with this year’s In bicycling, there are tours. Then hills and mountains of France. Indeed, to follow professional racing. From Giro d’Italia, a great race develops in there are Tours. And then there is by the time you read this, the gun will the Tour Down Under through the an unexpected way and I can hardly 4543 S. 700 E., Suite 200 wait to read the synopsis of each day’s Salt Lake City, UT 84107 action and follow the intrigue for the overall classification wins. www.cyclingutah.com But I especially get excited at Tour time. The Tour is, after all, the pinna- You can reach us by phone: cle of pro bike racing. And for almost (801) 268-2652 an entire month, I get to follow, watch and absorb the greatest cyclists of the Our Fax number: day battling it out for stage wins, jer- (801) 263-1010 sey points and overall classifications. -

CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018

CITY OF OREM CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018 This meeting may be held electronically to allow a Councilmember to participate. 4:30 P.M. WORK SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM PRESENTATION - North Pointe Solid Waste Special Service District (30 min) Presenter: Brenn Bybee and Rodger Harper DISCUSSION - SCERA Shell Study (15 min) Presenter: Steven Downs 5:00 P.M. STUDY SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM 1. PREVIEW UPCOMING AGENDA ITEMS Staff will present to the City Council a preview of upcoming agenda items. 2. AGENDA REVIEW The City Council will review the items on the agenda. 3. CITY COUNCIL - NEW BUSINESS This is an opportunity for members of the City Council to raise issues of information or concern. 6:00 P.M. REGULAR SESSION - COUNCIL CHAMBERS 4. CALL TO ORDER 5. INVOCATION/INSPIRATIONAL THOUGHT: BY INVITATION 6. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: BY INVITATION 7. PATRIOT DAY OBSERVANCE 7.1. PATRIOT DAY 2018 - In remembrance of 9/11 To honor those whose lives were lost or changed forever in the attacks on September 11, 2001, we will observe a moment of silence. Please stand and join us. 1 8. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 8.1. MINUTES - August 14, 2018 City Council Meeting MINUTES - August 28, 2018 City Council Meeting For review and approval 2018-08-14.ccmin DRAFT.docx 2018-08-28.ccmin DRAFT.docx 9. MAYOR’S REPORT/ITEMS REFERRED BY COUNCIL 9.1. APPOINTMENTS TO BOARDS AND COMMISSIONS Beautification Advisory Commission - Elaine Parker Senior Advisory Commission - Ernst Hlawatschek Applications for vacancies on boards and commissions for review and appointment Elaine Parker_BAC.pdf Ernst Hlawatschek_SrAC.pdf 10. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Royal Skousen Royal Skousen

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Royal Skousen Fundamental Scholarly Discoveries and Academic Accomplishments listed in an addendum first placed online in 2014 plus an additional statement regarding the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project from November 2014 through December 2018 13 May 2020 O in 2017-2020 in progress Royal Skousen Professor of Linguistics and English Language 4037 JFSB Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 [email protected] 801-422-3482 (office, with phone mail) 801-422-0906 (fax) personal born 5 August 1945 in Cleveland, Ohio married to Sirkku Unelma Härkönen, 24 June 1968 7 children 2 education 1963 graduated from Sunset High School, Beaverton, Oregon 1969 BA (major in English, minor in mathematics), Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1971 MA (linguistics), University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 1972 PhD (linguistics), University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois teaching positions 1970-1972 instructor of the introductory and advanced graduate courses in mathematical linguistics, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 1972-1979 assistant professor of linguistics, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 1979-1981 assistant professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1981-1986 associate professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1986-2001 professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah O 2001-2018 professor of linguistics and English language, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 2007-2010 associate chair, -

Utah Valley Chapter Newsletter

OCTOBER 1997 No. 2 OCTOBER CHAPTER MEETING Christmas in October? Of course. The season will be upon us sooner than we’d like to think, so we may as well be prepared for it. Have you arranged a carol or found an arrangement of a noel for prelude or postlude that you would like to share with us? Do you have an interesting way of playing a Christmas hymn for congregational singing? Take a minute and dig through your repertoire, before the snow flies, and see if AMERICAN there may be something you would like to present at the meeting. GUILD OF ORGANISTS We plan to do this sharing on Thursday, October 16th , at 7:30 p.m. at the Sunset Stake 1 9 9 7 Center, 1560 S. 1100 W., Provo (see directions on back). Thanks to Mary Paz for scheduling her meeting house for us, and to LuJean Moss for refreshments. Since we’d like to have a variety of Christmas music represented, it probably won’t do us any good to have 15+ arrangements or free accompaniments of Silent Night. In Utah Valley order to have things coordinated, please call DeeAnn Stone (377-4748 or email: [email protected]) with what you would like to do, so she can plan the program. Please Chapter call as soon as you can, so we’ll know who would like to participate. Carol Smart, Dean Newsletter of the Salt Lake Chapter, said that their chapter would like to join us, too. It will be a fun evening preparing for the Christmas season with them. -

Utah Valley Tower

UTAH VALLEY TOWER Water Gardens Cinema FOR LEASE ) DT 0 A 0,48 lvd. (3 ove B t Gr an as le P SITE UVBP - Site Plan 31 May 2019 Pleasant Grove Utah | Woodbury SITE PLAN Salt Lake City 52 Exchange Place SLC, UT 84111 801.531.1144 | Boise 800 W. Main Street Suite 940 Boise, ID 83702 208.424.7675 | babcockdesign.com 1050 SOUTH 4850 WEST | AMERICAN FORK, UTAH Marketed Exclusively by Developed by Brandon Fugal Jordan Wall Josh Smith +1 801 947 8300 +1 801 947 8300 +1 801 453 6823 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] UTAH VALLEY TOWER SAMPLE FLOOR PLAN Project Features • 150,000 square foot Class A office tower • Amenities include: Gym, Lounge, and Locker rooms, Gazebos for lunch seating, Sports courts, etc. • 5 X 30,000 square foot floor plates flfifi • Location is dynamic with unmatched I-15 exposure, • Lease rate: $28.50 PSF / FS redundant access to I-15, and it is the only • 18’ First floor ceilings, 14’ floor to floor on 2-5 opportunity zone office in Silicon Slopes. • • Parking ratio: 5.24/1,000 Expansion capability • Unique branding opportunities • Prime mountain views • Crown Signage SITE PLAN Developed By Brandon Fugal Jordan Wall Josh Smith UVBP - Site Plan 31 May 2019 This documentPleasant has been Grove prepared Utah by | Colliers Woodbury International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information in- +1 801 947 8300 +1 801 947 8300 +1 801 453 6823 SITE PLAN cluding, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy and reliability. -

Utah Valley Home Consortium: Housing Needs Assessment

April 2015 UTAH VALLEY HOME CONSORTIUM: HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT Prepared for: Redevelopment Agency of Provo City Corporation Prepared by: James Wood TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of Key Findings ................................................................................................................................ 3 Demographic Trends .......................................................................................................................... 3 Economic Trends ................................................................................................................................ 4 Housing Market Conditions .............................................................................................................. 4 Housing Needs Assessment ............................................................................................................... 7 I. Demographic Trends for Utah County and Consortium Cities.............................................................. 8 Demographic Trends .......................................................................................................................... 8 Population and Household Projections ........................................................................................... 9 Natural Increase and Migration ...................................................................................................... 10 Population and Household Characteristics ................................................................................... 10 Demographic -

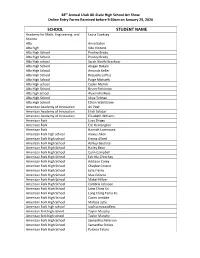

School Student Name

48th Annual Utah All-State High School Art Show Online Entry Forms Received before 9:30am on January 25, 2020 SCHOOL STUDENT NAME Academy for Math, Engineering, and Laura Cooksey Science Alta Anna Eaton Alta high Vito Vincent Alta High School Presley Brady Alta High School Presley Brady Alta High school Sarah Noelle Brashear Alta High School Abigail Hakala Alta High School Amanda Keller Alta High School Raquelle Loftiss Alta High School Paige Michaels Alta High school Caden Myrick Alta High School Brynn Parkinson Alta high school Alyxandra Rees Alta High School Miya Tolman Alta High School Ethan Wahlstrom American Academy of Innovation Ari Peel American Academy of Innovation Erick Salazar American Academy of Innovation Elisabeth Williams American Fork Lizzy Driggs American Fork Elle Kennington American Fork Hannah Lorenzana American Fork high school Alexus Allen American Fork High school Emma Allred American Fork High School Ashley Bautista American Fork High School Hailey Bean American Fork High School Colin Campbell American Fork High School Estrella Chinchay American Fork High School Addison Corey American Fork High School Chaylee Coston American Fork High School Julia Fierro American Fork High School Max Giforos American Fork High School Mabel Hillyer American Fork High School Cambria Johnson American Fork High School Long Ching Ko American Fork High School Long Ching Tania Ko American Fork High School Casen Lembke American Fork High School Malissa Lytle American Fork high school sophia mccandless American fork high school Taylor -

Project at a Glance May 31, 2010

Project At A Glance May 31, 2010 What is the proposed project? The Utah Transit Authority (UTA) and the Utah Depart- ment of Transportation (UDOT) propose to build a bus rapid transit (BRT) system through the cities of Provo and Orem in Utah County, Utah. The Provo-Orem BRT is a multi-modal project that addresses transit as well as roadway infrastructure needs. The Preferred Alternative, Project Details as shown on the Project Description Map includes: Length 11 miles Stations 22 ( 2 commuter rail ) • BRT service from the Orem Intermodal Center on the north to the Provo Intermodal Center and the Exclusive Lanes 71% Novell Campus on the south Parking Saved at UVU and BYU 6 acres • Exclusive lanes for approximately 71% of the route Corridor Person Capacity 22-36% increase Project Statistics Current Bus Current BRT Route 830 Projections 2012 Ridership 14,200 / day 3,600 / day • Visually pleasing station designs built for shelter 2030 Ridership 16,900 / day and comfort Frequency 15 mins 5 mins 37-38 mins Travel Time 46 mins ( 42 mins by car ) Car Trips Converted to Transit 5,000 Cost Transit Signal Priority (TSP) Transit Improvements $130 - $200 million Signal priority allows buses to arrive and travel through intersections with little or no delay. Detectors identify and Roadway Improvements $20 - $80 million distinguish buses from other vehicles. The detectors then give priority to the buses by manipulating the traffic lights Total $150 - $280 million to give the buses a green light. Provo-Orem Rapid Transit 1 Cougar Stadium, University Parkway, Provo, Utah • Enhanced, real-time transit information at stations (HOV) interchange. -

Newletter Template

Week of January 20th, 2020 Alta High School Ignite the Hawk Within We are an inclusive learning community with a tradition of inspiring, supporting, and collaborating with students as they prepare to be engaged citizens in their pursuit of continuous success. ü Step2TheU Program – It is time for Alta’s 11th grade students to start considering applying for our Step2TheU Program. For more information, please visit the Step2TheU webpage. Applications are due February 3, 2020. You can also order your transcripts by going online here or through the Alta website. Please allow 2 business days to process your request. ü Interested in Concurrent Enrollment? – Join us for an informational meeting on January 21st. See additional page for more details. ü After School Tutoring – At Alta, we provide many options for students to obtain help if they are struggling in one or more of their classes. Please visit the After School Tutoring page on the Alta website for more information. You can also view a schedule for Math Lab and Computer Lab below. ü Girls and Boys State – Applications for Girls and Boys State are now available to all 11th grade students. This is a great opportunity to earn college credit, learn about government and citizenship and spend time with students from all over the state. This looks great on college and scholarship applications! Space is limited for these programs, so you will want to apply today. The application deadline for Girls State is February 10th. Boys State applications are due in April. See the additional pages for more information. Application information is also available in the Alta Counseling Office. -

Print 2003 Spring Prospectus2

VOLLEYBALL 2005 PROSPECTUS BYU COUGARS ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS 30 Smith Fieldhouse • Provo, Utah 84602 • Tel: (801) 422-8999 • Fax: (801) 422-0633 2005 QUICK FACTS WOMEN’S VOLLEYBALL UNIVERSITY INFORMATION 2005 PROSPECTUS Location . .Provo, Utah 84602 Elevation . .4,553 feet Enrollment . .32,122 (Daytime) 2005 Season Preview Founded . .October 15, 1875 After finishing the 2004 season at 19-11 overall and third in the Mountain West Conference with a 9-5 Owned . .Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints record, BYU is looking to challenge for the conference title and return to the NCAA Tournament in 2005. Nickname . .Cougars Mascot . .Cosmo The Cougars will rely on an experienced group of returning players and a new coaching staff to achieve their goals. Colors . .Dark blue, white and tan Conference . .Mountain West Jason Watson, who has 11 years of collegiate coaching experience as an assistant at four universities including three as an assistant at BYU, was named head coach of the program after the departure of Arena . .Smith Fieldhouse (5,000) wood floor Karen Lamb. Brooke Huebner, back for her second season on the sidelines, and recently hired Brent BYU President . .Cecil O. Samuelson (Utah, 1970) Aldridge will be Watson’s assistants. Aldridge comes to BYU with 12 years of coaching experience at Athletics Director . .Tom Holmoe (BYU, 1983) the collegiate, high school and club levels. He most recently served as an assistant at the University of New Mexico for three seasons. VOLLEYBALL INFORMATION With the return of 10 letterwinners, including six starters, Watson is optimistic about the Cougars’ potential to make a run for the MWC Championship. -

(School Resource Officers) This Agreement Is Executed in Duplicate

AMENDED INTERLOCAL AGREEMENT (School Resource Officers) This Agreement is executed in duplicate this ____ day of ______________________, 2018, by and between the City of Orem, a municipal corporation and political subdivision of the State of Utah, with its principal offices located at 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah 84057, (hereinafter referred to as the “City”), and the Board of Education, Alpine School District, a corporation and political subdivision of the State of Utah, with its principal offices located at 575 North 100 East, American Fork, Utah 84003 (hereinafter referred to as “Alpine”). WHEREAS, Alpine was created for the purpose of educating, training, developing, and ensuring the academic excellence of the youth of its district; and WHEREAS, Alpine has established a reputation for excellence in the quality of its schools and the resulting level of achievement by its students; and WHEREAS, juvenile crime and school violence continues to escalate nationally and in the State of Utah and without appropriate intervention, youthful offenders are more likely to repeat and even increase their level of criminal activity; and WHEREAS, youth can sometimes be a disruptive influence on others as their involvement in gang and criminal activity is carried onto the school campus; and WHEREAS, the resulting cost to both victims and the criminal justice system becomes an increasing burden to the community; and WHEREAS, Alpine and the City are mutually supportive of efforts to engage in activities which promote the prevention and detection -

Click Here to Search to Get Phone Data Faster, Please Click to Search

Click here to search To get phone data faster, please click to search button! (801) 224-6243 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-7555 Larry Ashby PROVO,579 E 4750 N More info (801) 224-9646 Andy Sherwin Provo,4274 N. Sheffield Drive More info (801) 224-3225 Fritz Fui Orem,232 E 1600 S More info (801) 224-8198 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-8735 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5558 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-8438 Layne Izatt Orem,526 W 1085 N More info (801) 224-2948 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-4184 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-1033 Yolanda Renteria Vineyard,425 E 1600 N More info (801) 224-6452 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5052 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-7022 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5513 David Stoddard Orem,1260 Farm Lane Circle More info (801) 224-1868 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-6770 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-9188 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-8555 Daniel H. Jensen Orem,852 S State Street More info (801) 224-1908 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-0179 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5122 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-9273 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5313 Kathleen Olsen , More info (801) 224-5387 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-2542 Apex Alarm Provo,4778 North 300 West More info (801) 224-0552 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-5702 Available Data Avaiable More info (801) 224-7926 Willy