AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Michelle M. Huillet for the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Value of Student Feedback in Open Forums: a Natural Analysis of Descriptions of Poorly Rated Teachers

education policy analysis archives A peer-reviewed, independent, open access, multilingual journal Arizona State University Volume 29 Number 79 June 7, 2021 ISSN 1068-2341 The Value of Student Feedback in Open Forums: A Natural Language Analysis of Descriptions of Poorly Rated Teachers Carlos Valcarcel Jefferey Holmes David C. Berliner & Mari Koerner Arizona State University United States Citation: Valcarcel, C., Holmes, J. Berliner, D. C., & Koerner, M. (2021). The value of student feedback in open forums: A natural analysis of descriptions of poorly rated teachers. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 29(79). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.29.6289 Abstract: In this paper we used natural language processing to review hundreds of thousands of negative student reviews of their teachers submitted to the website RateMyTeacher.com. Our analysis identified several issues raised by students when rating teachers poorly, which adds to the literature that defines “bad teachers” from the student perspective. We also identify the language students used to describe these issues and notice a clear distinction between the language used to address teaching-related complaints and behavior perceived as unfit for teachers. We argue that digital forums can be valuable tools for schools and conclude with suggestions and examples of the type of policies that may be derived from this type of analysis of a digital forum for students. Keywords: student evaluation of teacher performance; natural language processing; feedback (response); school policy; high schools; middle schools Journal website: http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/ Manuscript received: 20/11/2020 Facebook: /EPAAA Revisions received: 3/18/2021 Twitter: @epaa_aape Accepted: 3/19/2021 Education Policy Analysis Archives Vol. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

Larry Sidor Oral History Interview, November 6, 2015 Title “From Olympia to Deschutes to Crux: A Brewer's Life” Date November 6, 2015 Location Valley Library, Oregon State University. Summary In the interview, Sidor discusses his family background and rural upbringing in La Grande, Oregon, commenting on his father's activities as an OSU Extension Agent, his own boyhood interests in mechanical work, and the life histories of his mother and his siblings. From there, Sidor recounts his undergraduate years at Oregon State University, noting his switch in majors from Mechanical Engineering to Food Science, and commenting on the curriculum then available to undergraduates in the Food Science department. Sidor likewise reflects on the research that he conducted while a student and, in particular, his interest in winemaking during that time. From there, Sidor details the circumstances by which he declined a handful of job opportunities in the wine industry, opted instead to travel for a year in Europe, and began considering a career in brewing as a result of his experiences in Germany. He then traces his first connection with the Olympia Brewing Company; outlines his advancement within the company from packing quality control technician, to assistant brewmaster, to operations manager; shares his perspective on the brewing culture then prevalent at Olympia; and speaks of the connections that he made with hop growers in Washington and Oregon. Sidor next provides an overview of his years working at the S.S. Steiner company, shares his memories of the rise of microbreweries in the 1980s and 1990s, and reflects on the relationships that Steiner maintained with agricultural scientists at OSU. -

Unlisted Properties: an Exploration in Solo Performance

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Unlisted Properties: An Exploration in Solo Performance Jason Smith Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Jason Edward Smith and Lauren Marinelli White, 2008 All Rights Reserved UNLISTED PROPERTIES: AN EXPLORATION IN SOLO PERFORMANCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by LAUREN MARINELLI WHITE B.A., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2002 and JASON EDWARD SMITH B.A., The College of William and Mary, 2004 Director: DR. TAWNYA PETTIFORD-WATES ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ACTING AND DIRECTING, THEATRE Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2008 ii Acknowledgement Lauren and Jase would first and foremost like to thank our mentor, Dr. Tawnya Pettiford-Wates, for her unwavering support, encouragement, friendship and tenacious loyalty. Without her guidance, neither this project nor our journeys in this program would have been as fulfilling and enriching as we will always remember them to be. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Noreen Barnes and David McLain, MFA for their unique perspectives and valuable guidance. We would also like to thank the creative talents of those involved with the development of this project: Melissa Carroll-Jackson, Jenna Ferre, Ron Keller, Kevin McGranahan, Carol Piersol, Tommy Pruitt, Kay Stone, and Shanea N. -

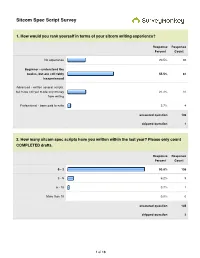

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Act One Fade In: Int. Studio Backstage

30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 1. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 ACT ONE FADE IN: 1 INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - NIGHT 1 The show is in full swing. We hear a laugh from inside the studio, then applause and the band kicking in. The double doors burst open and JENNA, dressed as a fat old lady, LIZ, and a QUICK-CHANGE DRESSER enter the backstage chaos from the studio. In the background we see the STAGE MANAGER. STAGE MANAGER We’re back in two minutes! The dresser starts going to work on Jenna; tearing off a wig, casting aside props and jewelry. PETE is there. JENNA (to Liz) So are you gonna ask out the Head? Liz rolls her eyes. PETE The “Head”? LIZ There are these two MSNBC guys we keep seeing around. They just moved offices from New Jersey. We don’t know their names so we call them the Head and the Hair. PETE How come? FLASH BACK TO: 2 INT. ELEVATOR/ELEVATOR BANK - EARLIER THAT DAY 2 Liz and Jenna are on the elevator coming in to work. Two guys get on. One guy is super handsome and has great hair. This is THE HAIR, GRAY. The other guy is cranial and nerdy looking. This is THE HEAD. Liz smiles politely. Jenna gives the Hair a huge grin. GRAY Hey! You guys again. Jenna laughs too hard at this non-joke. 30 ROCK 113: "The Head and The Hair" 2. Shooting Draft Third Revised (Yellow) 12/13/06 JENNA How are things going? Are you settling in okay? GRAY We’re finding our way around. -

A Family Christmas Devotional

A FAMILY CHRISTMAS DEVOTIONAL 1 A devotional focused on the events of 2020 2 What a year … While it probably seems a little cliche at this point, we recognize that 2020 has been a year unlike any in recent memory. From a global pandemic, to civic unrest, to an extremely contentious election season, it has often seemed like Hell must be throwing everything at us (including the kitchen sink). We are all worn and weary, and in need of some rest and hope. Unfortunately, the holidays are often anything but restful, aren’t they? If anything, the days are filled with nonstop to-do’s, activities, more stress, and the rush to “fit everything in.” For many of us, it can feel like we’re just barely making it to New Year’s alive. And in the midst of the frenzy and stress, we often miss what this season is truly all about. Does the true meaning of Christmas even matter anymore? Are we just running around all month for silly, old-fashioned traditions? Most of us probably know that all of this began with a story in the Bible, but how do we know we can even trust that anymore? And if we can’t trust it, then why are we adding more stress and busyness at the end of a long, stressful year? If you’ve ever wondered in your own spirit if all of this really matters, don’t worry; you’re not alone! All of the questions are understandable – especially this year – but especially because of how stressful this year has been, we want to help point you and your loved ones back to the true meaning of Christmas. -

Idea Xxviii/2 2016

Rada Redakcyjna: Mira Czarnawska (Warszawa), Zbigniew Kaźmierczak (Białystok), Andrzej Kisielewski (Białystok), Jerzy Kopania (Białystok), Małgorzata Kowalska (Białystok), Dariusz Kubok (Katowice) Rada Naukowa: Adam Drozdek, PhD Associate Professor, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA Anna Grzegorczyk, prof. dr hab., UAM w Poznaniu Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr., Uniwersytet Pavla Jozefa Šafárika w Koszycach, Słowacja Marek Maciejczak, prof. dr hab., Wydział Administracji i Nauk Społecznych, Politechnika Warszawska David Ost, Joseph DiGangi Professor of Political Science, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, USA Teresa Pękala, prof. dr hab., UMCS w Lublinie Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Ilahiyat Fakultesi (Wydział Teologii), Konya, Turcja Recenzenci: Vladimír Leško, Prof. PhDr. Andrzej Niemczuk, dr hab. Andrzej Noras, prof. dr hab. Tahir Uluç, PhD Associate Professor Redakcja: dr hab. Sławomir Raube (redaktor naczelny) dr Agata Rozumko, mgr Karol Więch (sekretarze) dr hab. Dariusz Kulesza, prof. UwB (redaktor językowy) dr Kirk Palmer (redaktor językowy, native speaker) Korekta: Zespół Projekt okładki i strony tytułowej: Tomasz Czarnawski Redakcja techniczna: Ewa Frymus-Dąbrowska ADRES REDAKCJI: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku Plac Uniwersytecki 1 15-420 Białystok e-mail: [email protected] http://filologia.uwb.edu.pl/idea/idea.htm ISSN 0860–4487 © Copyright by Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Białystok 2016 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku 15–097 Białystok, ul. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie 14, tel. 857457120 http://wydawnictwo.uwb.edu.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Skład, druk i oprawa: Wydawnictwo PRYMAT, Mariusz Śliwowski, ul. Kolejowa 19, 15-701 Białystok, tel. 602 766 304, 881 766 304, e-mail: [email protected] SPIS TREŚCI WOJCIECH JÓZEF BURSZTA: Homo Barbarus w świecie algorytmów ................................................................................................. 5 ZBIGNIEW KAŹMIERCZAK: Demoniczność Boga jako założenie ekskluzywistycznego i inkluzywistycznego teizmu .................................. -

TÄYDELLINEN MYSTEERI - Mysteerin Anatomia Täydellisissä Naisissa

Opinnäytetyö (AMK) Viestintä Elokuva 2010 Tiina Tanskanen TÄYDELLINEN MYSTEERI - Mysteerin anatomia Täydellisissä naisissa OPINNÄYTETYÖ (AMK) | TIIVISTELMÄ TURUN AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU Viestintä | Elokuva 6. toukokuuta 2010 | 31 sivua Vesa Kankaanpää Tanskanen, Tiina TÄYDELLINEN MYSTEERI Tarkastelen tässä kirjallisessa opinnäytetyössä Täydellisten naisten (Desperate Houwewives) ensimmäisen tuotantokauden mysteerijuonta käsikirjoitukselliselta kantilta. Täydelliset naiset on Abc Studiosin ja Cherry Productionsin tuottama tv-sarja, jota on vuoteen 2010 mennessä tuotettu kuusi kautta. Sarjan on luonut Marc Cherry. Aluksi käyn lyhyesti läpi mysteeritarinoiden historiaa ja pureudun sen jälkeen tutkimaan Täydellisten naisten ensimmäisen kauden mysteeriä, joka liittyy sarjan hahmon Mary-Alice Youngin itsemurhan syyn selvittämiseen. Tarkastelen mysteerin rakennetta käyttämällä hyväksi Syd Fieldin esittelemää rakenneparadigmaa. Selvitän mysteerin luomiseen käytettäviä käsikirjoituksellisia elementtejä ja pohdin, minkälaisia ongelmia mysteerin venytys 23 jakson kaudelle saattaa aiheuttaa. Yhteenvetona listaan tekijöitä, jotka ovat olennaisessa osassa mysteeritarinan kirjoittamisessa. Lopuksi pohdiskelen mysteerin ratkaisun ja sen luoman jännityksen suhdetta ja vertailen Täydellisten naisten mysteeriä muutamiin muihin tv-sarjoihin, jotka käyttävät samantapaista rakennetta. ASIASANAT: käsikirjoittaminen, televisio-ohjelmat, mysteeri BACHELOR´S THESIS | ABSTRACT UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Media arts | Film art 6.5.2010 | 31 pages Vesa Kankaanpää Tanskanen -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

Emma Dornerus Breaking Maxims in Conversation a Comparative

Institutionen för kultur och kommunikation Emma Dornerus Breaking maxims in conversation A comparative study of how scriptwriters break maxims in Desperate Housewives and That 70’s Show Engelska C-uppsats Datum/Termin: Höstterminen 2005 Handledare: Michael Wherrity Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND AIM ............................................................................................. 1 2. BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................2 2.1 PRAGMATICS ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 GRICE ................................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Implicature ................................................................................................................ 4 2.2.2 The Cooperative Principle ........................................................................................ 4 2.2.3 Conversational maxims............................................................................................. 5 2.2.3.1 The maxim of quantity............................................................................................ 5 2.2.3.2 The maxim of quality.............................................................................................. 5 2.2.3.3 The maxim of -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened.