C 4. Sal~Crella-Grit and Quartzite. Zoch Broom (P. 363)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holochoanites Are Endoceroids Rousseau H

HOLOCHOANITES ARE ENDOCEROIDS ROUSSEAU H. FLOWER, New York State Museum Albany 1, N. Y. INTRODUCTION The Holochoanites may be defined as those cephalopods in which the septal necks are so elongated that they extend from the septum of which they are a part and a prolongation, apicad to the next septum, or even farther. Hyatt (1884) first regarded the Holochoanoidea as one of two major divisions of the Nautiloidea. Later (1900) he replaced his other division, the Ellipochoanoidea, by four divisions the Orthochaonites, Cyrtochoanites, Schistochoanites and Mixochoanites, and changed the name Holochoanoidea to Holochoanites for uniformity. In the mean- time, further study caused him to modify the contents of the holochoanitic division materially. Some genera originally placed in this group, such as Trocholites, proved upon further study to possess ellipochoanitic septal necks. The genus Aturia, while properly holochoanitic, was removed, because it was recognized that it represented a development of elongated septal necks in Tertiary time, which was obviously quite unrelated to that of other holochoanitic cephalopods, few of which survived the close of the Ordovician. Miller and Thompson (1937) showed that the elongation of the septal necks in Aturia was a secondary feature and the ellipochoanitic ancestry was indicated by the retention of connecting rings. It was believed that the Holochaonites proper contain cephalopods in which the long necks were primitive, and no connecting rings were developed. Unfortunately Hyatt does not seem to have committed himself on his ideas concerning the relationship of the Holochoanites with other cephalopods. It is not clear whether this was because of his preoccupation with the phyletic sig- nificance of early stages and the controversy that developed about the origin of the Ammonoidea and their relationship to the Nautiloidea, or whether he was as much perplexed by the problem as have been those of us who have come after him in the study of cephalopods. -

Prehistoric Giants (Other Than Dinosaurs) Level Y Leveled Book Correlation Written by Alfred J

Prehistoric Giants LEVELED BOOK • Y (Other Than Dinosaurs) A Reading A–Z Level Y Leveled Book Prehistoric Giants Word Count: 2,161 (Other Than Dinosaurs) Written by Alfred J. Smuskiewicz Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Front cover, pages 9, 13, 16, 17: © DEA PICTURE LIBRARY/age fotostock; back cover: © Dean Mitchell/Alamy; title page: © Dirk Wiersma/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 3: © John Reader/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 6: © DK Images; page 8: Jon Hughes/Bedrock Studios © Dorling Kindersley; Prehistoric Giants page 11: © Sheila Terry/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 12 (left): © Richard Ellis/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; pages 12 (right), 15, 22 (left): © Hemera Technologies/Jupiterimages Corporation; page 14: © Chris Butler/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 18: © Roger Harris/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; (Other Than Dinosaurs) page 19: © Jupiterimages Corporation; page 20: Mick Loates © Dorling Kindersley; page 21: © Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 22 (right): © iStockphoto.com/Yael Miller Front cover: Gastornis attacks prey. Back cover: Emu feet look as if they might belong to a prehistoric animal like Gastornis. Title page: fossils of marine life from between 470 million and 360 million years ago Table of Contents: Georges Cuvier (portrait, top left) defined the ways scientists decide how an extinct animal, such as Megatherium (top), might look. Geologist William Buckland (foreground, left) found a tiny mammal’s jaw bone (under magnifying glass) with a dinosaur’s toe bone, which led him and Cuvier to decide that mammals had lived in more ancient times than anyone had ever known. -

1540 Evans.Vp

An early Silurian (Aeronian) cephalopod fauna from Kopet-Dagh, north-eastern Iran: including the earliest records of non-orthocerid cephalopods from the Silurian of Northern Gondwana DAVID H. EVANS, MANSOUREH GHOBADI POUR, LEONID E. POPOV & HADI JAHANGIR The cephalopod fauna from the Aeronian Qarebil Limestone of north-eastern Iran comprises the first comprehensive re- cord of early Silurian cephalopods from peri-Gondwana. Although consisting of relatively few taxa, the assemblage in- cludes members of the orders Oncocerida, Discosorida, Barrandeocerida and Orthocerida. Coeval records of several of these taxa are from low palaeolatitude locations that include Laurentia, Siberia, Baltica and Avalonia, and are otherwise unknown from peri-Gondwana until later in the Silurian. The cephalopod assemblage occurs in cephalopod limestones that currently represent the oldest record of such limestones in the Silurian of the peri-Gondwana margin. The appear- ance of these cephalopods, together with the development of cephalopod limestones may be attributed to the relatively low latitudinal position of central Iran and Kopet-Dagh compared with that of the west Mediterranean sector during the Aeronian. This, combined with the continued post-glacial warming after the Hirnantian glaciation, facilitated the initia- tion of carbonate deposition and conditions suitable for the development of the cephalopod limestones whilst permitting the migration of cephalopod taxa, many of which were previously restricted to lower latitudes. • Key words: Llandovery, Aeronian, Cephalopoda, palaebiogeography, peri-Gondwana. EVANS, D.H., GHOBADI POUR, M., POPOV,L.E.&JAHANGIR, H. 2015. An Early Silurian (Aeronian) cephalopod fauna from Kopet-Dagh, north-eastern Iran: including the earliest records of non-orthocerid cephalopods from the Silurian of Northern Gondwana. -

Cephalopod Reproductive Strategies Derived from Embryonic Shell Size

Biol. Rev. (2017), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12341 Cephalopod embryonic shells as a tool to reconstruct reproductive strategies in extinct taxa Vladimir Laptikhovsky1,∗, Svetlana Nikolaeva2,3,4 and Mikhail Rogov5 1Fisheries Division, Cefas, Lowestoft, NR33 0HT, U.K. 2Department of Earth Sciences Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, U.K. 3Laboratory of Molluscs Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117997, Russia 4Laboratory of Stratigraphy of Oil and Gas Bearing Reservoirs Kazan Federal University, Kazan, 420000, Russia 5Department of Stratigraphy Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119017, Russia ABSTRACT An exhaustive study of existing data on the relationship between egg size and maximum size of embryonic shells in 42 species of extant cephalopods demonstrated that these values are approximately equal regardless of taxonomy and shell morphology. Egg size is also approximately equal to mantle length of hatchlings in 45 cephalopod species with rudimentary shells. Paired data on the size of the initial chamber versus embryonic shell in 235 species of Ammonoidea, 46 Bactritida, 13 Nautilida, 22 Orthocerida, 8 Tarphycerida, 4 Oncocerida, 1 Belemnoidea, 4 Sepiida and 1 Spirulida demonstrated that, although there is a positive relationship between these parameters in some taxa, initial chamber size cannot be used to predict egg size in extinct cephalopods; the size of the embryonic shell may be more appropriate for this task. The evolution of reproductive strategies in cephalopods in the geological past was marked by an increasing significance of small-egged taxa, as is also seen in simultaneously evolving fish taxa. Key words: embryonic shell, initial chamber, hatchling, egg size, Cephalopoda, Ammonoidea, reproductive strategy, Nautilida, Coleoidea. -

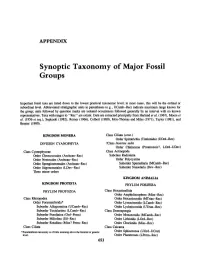

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Ordovician Fauna

II ORDOVICIAN FAUNA By ARTHUR C. McFARLAN THE ORDOVICIAN FAUNA OF KENTUCKY By ARTHUR C. McFARLAN INTRODUCTION HIGH BRIDGE SERIES (M. R. CAMPBELL, 1898) Massive, cliff-forming limestone of Chazy and Stones River age. Three formations are recognized: CAMP NELSON (A. M. Miller, 1905, p. 10). Limestone composed of irregular patches and ramifications of granular rock of the Oregon type distributed through a matrix of dense limestone of the Tyrone type, presumably algal in origin. On weathering the surface becomes honeycombed. Fossils are not common, the more characteristic being Maclurites bigsbyi, Escharopora ramosa, a species of Rhinidictya, and various cephalopods. OREGON—Kentucky River Marble (A. M. Miller, 1905, p. 10). Grey to cream colored, granular, magnesian limestone. TYRONE—Birdseye Limestone of Linney (A. M. Miller, 1905, p. 10). Dense gray, dove, or cream colored limestone, breaking with conchoidal fracture and with small facets of Fig. 25. Map of Kentucky showing outcrop of Ordovician rocks. 50 THE PALEONTOLOGY OF KENTUCKY coarsely crystalline calcite. On weathering the surface becomes white, in which the darker facets are conspicuous, giving rise to the name Birdseye. A bed of bentonite, a greenish clay, occurs near the top. Fossils are few and include such forms as Strophomena incurvata, (see p. 80) Orthis tricenaria, Leperditia fabulites, and the cephalopods Endoceras, Actinoceras, and Cameroceras. LEXINGTON LIMESTONE (M. R. Campbell, 1898) This is the Trenton of Kentucky. As originally defined it included the strata between the Tyrone and Flanagan Chert. As later applied by Miller (1905, p. 18) and Foerste everything up to the base of the Cynthiana is included. -

Part III. an Inquiry Into the Sedimentary and Other External Relations of the Pa,Lceozoic Fossils of the State of New York ~

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at Orta Dogu Teknik Universitesi251 on January 17, 2016 POSTPONED PAPERS. On the PALmozoIe BASIN of the STAT~ of N~W Yo~K. Part III. An Inquiry into the Sedimentary and other External Relations of the Pa,lceozoic Fossils of the State of New York ~. By J. J. BrassY, M.D., V.P.G.S., formerly British Secretary to the Canadian Boundary Commission. [Read May 26, 1858.] CONTENTS. Introduction. § 1. Conditions and characters of Sediments. § 2. Palmozoic Sediments; their nature. § 3. On the Distribution and immediate relations of Palmozolc Animal Life in Wales and the State of New York. a. Calcareous Strata. b. Argillaceous Strata. c. Arenaceous Strata. d. Fos- sils in Calcareous and Non-calcareous Strata. e. Divergence. f. Recur- rence, g. Recurrence of Orders and Genera. h. Reeurrents of the De- vonian System of"New York. 4. On the grouping of Fossils, and their Order of Precedence. 1. Potsdam Sandstone. 2. Calciferous Sandstone. 3. Chazy or Black- river Limestone. 4. Birdseye Limestone. 5. Trenton Limestone. 6. Utica Slate. 7. Hudson-river Rocks. 8. ]~Iedina Sandstone. 9. Clinton Rocks. § 5. Increment and Decrement. § 6. Duration of Invertebrate Life. § 7. Epochal and Geographical Diffusion of Species. §8. Recurrence. §' 9. Comparison of the Palmozoie Basins of Wales and New York. Introductlon.---The objects proposed in this inquiry are--to give more precision to facts as yet imperfectly ascertained, and to discover, if possible, new materials for the history of these early times, and new points of connexion between the palaeozoic basins of the State of New York and of Wales--countries which axe therefore the sub- ject of frequent comparison in these pages. -

A Remarkable Nautiloid from the Second Value of New Mexico

MEMOIR 21 PART I Botryceras, A Remarkable Nautiloid from the Second Value of New Mexico PART II An Endoceroid from the Mohawkian of Quebec PART III Endoceroids from the Canadian of Alaska PART IV A Chazyan Cephalopod Fauna from Alaska by ROUSSEAU H. FLOWER 1968 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY Stirling A. Colgate, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Frank E. Kottlowski, Acting Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS Ex OFFICIO THE HONORABLE DAVID F. CARGO ........................ Governor of New Mexico LEONARD DELAYO .................................... Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS WILLIAM G. ABBOTT ................................................................ Hobbs EUGENE L. COULSON, M.D. ................................................................. Socorro THOMAS M. CRAMER ...................................................................... Carlsbad STEVE S. TORRES, JR. ....................................................................................... Socorro RICHARD M. ZIMMERLY ................................................................. Socorro Published July 31, 1968 For sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex. 87801—Price $2.00 Contents Page PART I ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... -

Lab 8: Ordovician Observations

Lab 8: Ordovician Observations How This Lab Will Work 1. Open a Word doc or similar on your computer 2. At various points I will ask you to answer a question based on the activities in this lab. 3. I will indicate these points by this symbol: Please answer these questions in your Word doc. 4. After you have assembled the answers into your Word doc, go to the course Canvas page. 5. On the module for this week there is a link to TurnItIn. 6. Please upload your document using the TurnInIt. 7. That completes the lab assignment. :) Reminder on Observation Project Please remember that as we go through these, you should be using these fossils to construct your lab observation project, which was detailed last time. Easy to put off, hard to catch up. ;) Topics Today 1. Introduction to Ordovician 2. Phylum Cnidaria: Rugose Coral 3. Phylum Hemichordata: Graptolites 4. Phylum Echinodermata: Crinoids 5. Phylum Arthropoda: Trilobite 6. Phylum Arthropoda: Eurypterids 7. Phylum Bryozoa 8. Phylum Brachiopoda: Inarticulata 9. Phylum Brachiopoda: Artriculata 10. Phylum Mollusca: Gastropods 11. Phylum Mollusca: Cephalopods 12. Phylum Chordata: First Fishes Introduction to the Ordovician Following the mass extinction ending the Cambrian, the Ordovician (488 - 443 Ma) marked a brilliant proliferation of Cambrian life into new and more complicated forms. Many organisms secreted carbonate shells, usually first in the form of aragonite (CaCO3), Geology 121 Lab 8: Ordovician, page 1 of 9 which often quickly converted to its polymorph calcite (CaCO3). This organic precipitation of carbonate became a major sedimentary rock type, as well as the material for shelly fossil preservation. -

The Paleoecology of a Late Ordovician Shale Unit from Southwest Ohio and Southeastern Indiana Author(S): Robert C

Paleontological Society The Paleoecology of a Late Ordovician Shale Unit from Southwest Ohio and Southeastern Indiana Author(s): Robert C. Frey Source: Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Mar., 1987), pp. 242-267 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1305320 Accessed: 14/03/2010 21:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sepm and http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=paleo. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Paleontological Society and SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Paleontology. -

Prehistoric Giants LEVELED BOOK • Y (Other Than Dinosaurs) a Reading A–Z Level Y Leveled Book Prehistoric Giants Word Count: 2,161 (Other Than Dinosaurs)

Prehistoric Giants LEVELED BOOK • Y (Other Than Dinosaurs) A Reading A–Z Level Y Leveled Book Prehistoric Giants Word Count: 2,161 (Other Than Dinosaurs) Written by Alfred J. Smuskiewicz Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Glossary tentacles (n.) long, flexible armlike growths on an animal Front cover, pages 9, 13, 16, 17: © DEA PICTURE LIBRARY/age fotostock; that the animal uses to feel things, to hold back cover: © Dean Mitchell/Alamy; title page: © Dirk Wiersma/SPL/Photo amphibians (n.) animals that live part of their lives in water Researchers, Inc.; page 3: © John Reader/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 6: things, or to move (p . 6) and part on land (p . 4) © DK Images; page 8: Jon Hughes/Bedrock Studios © Dorling Kindersley; Prehistoric Giants page 11: © Sheila Terry/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 12 (left): © Richard trilobites (n.) common prehistoric sea animals that were arthropod (n.) any animal whose body has a hard covering Ellis/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; pages 12 (right), 15, 22 (left): © Hemera covered with a soft shell (p . 6) and jointed legs, including insects, crabs, Technologies/Jupiterimages Corporation; page 14: © Chris Butler/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 18: © Roger Harris/SPL/Photo Researchers, Inc.; lobsters, spiders, and centipedes (p . 9) (Other Than Dinosaurs) page 19: © Jupiterimages Corporation; page 20: Mick Loates © Dorling Index Kindersley; page 21: © Photo Researchers, Inc.; page 22 (right): DNA a chemical in cells that has instructions for the © iStockphoto.com/Yael Miller (deoxyribonucleic formation and growth of new cells and new amphibian, 4, 10, 11 insect, 4, 8, 9 Front cover: Gastornis attacks prey. -

Guide to Evolve Or Perish ETE’S Game of Life Through the Ages

Guide to Evolve or Perish ETE’s game of life through the ages This guide explains images created by Hannah Bonner for the Evolution of Terrestrial Ecosystems Program Game, Evolve or Perish, with information gathered by Erin Embrey (2012 NMNH Intern) under the supervision of Abby Telfer, NMNH FossiLab Manager. Download game at https://naturalhistory.si.edu/education/teaching-resources/paleontology/evolve-or-perish-board-game Some help with abbreviations and names… • mya = millions of years ago • Meganeuropsis permiana - This is an example of a scientific name of a plant or animal, in this case the giant fossil dragonfly. The first name is the Genus, the second is the species. The proper way to write these names is in italics, so it is clear they are the official Latin names. • To learn how to pronounce the names, we encourage you to look them up on-line! Names of Geological Time Intervals used in Evolve or Perish (oldest to youngest): Proterozoic: Ediacaran Paleozoic: Mesozoic Cenozoic Cambrian Triassic Paleogene Ordovician Jurassic Neogene Silurian Cretaceous Devonian Carboniferous (includes Pennsylvanian) Permian Note: The animals and plants depicted in Evolve or Perish are based on actual fossils and information gathered by many generations of paleontologists who have studied them. The artist, Hannah Bonner, remained true to the science but imagined colors and other features for which there is no fossil record. Ediacaran Charnia (635-542 mya): A benthic animal (living at the bottom of a body of water) that was widespread during the Ediacaran. It is sometimes mistaken for a plant because of its shape.