Bound: Documentation and Home- Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank Mobley Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ—¶É—´È¡¨)

Hank Mobley 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) Roll Call https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roll-call-7360871/songs Tenor Conclave https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/tenor-conclave-3518140/songs Hi Voltage https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hi-voltage-5750435/songs No Room for Squares https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/no-room-for-squares-7044921/songs Hank Mobley Sextet https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hank-mobley-sextet-5648411/songs Mobley's Message https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mobley%27s-message-6887376/songs Straight No Filter https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/straight-no-filter-7621018/songs Jazz Message No. 2 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/jazz-message-no.-2-6168276/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs A Slice of the Top https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-slice-of-the-top-4659583/songs The Turnaround! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-turnaround%21-7770743/songs A Caddy for Daddy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-caddy-for-daddy-4655701/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-jazz-message-of-hank-mobley- The Jazz Message of Hank Mobley 7743041/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hank-mobley-and-his-all-stars- Hank Mobley and His All Stars 5648413/songs Far Away Lands https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/far-away-lands-5434501/songs Third Season https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/third-season-7784949/songs Hank Mobley Quartet -

The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 Recollections of Past Days: The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer Sandra Ailey Petree Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Archer, P. L., & Petree, S. A. (2006). Recollections of past days: The autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recollections of Past Days The Autobiography of PATIENCE LOADER ROZSA ARCHER Edited by Sandra Ailey Petree Recollections of Past Days The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer Volume 8 Life Writings of Frontier Women A Series Edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher Volume 1 Winter Quarters The 1846 –1848 Life Writings of Mary Haskin Parker Richards Edited by Maurine Carr Ward Volume 2 Mormon Midwife The 1846 –1888 Diaries of Patty Bartlett Sessions Edited by Donna Toland Smart Volume 3 The History of Louisa Barnes Pratt Being the Autobiography of a Mormon Missionary Widow and Pioneer Edited by S. George Ellsworth Volume 4 Out of the Black Patch The Autobiography of Effi e Marquess Carmack Folk Musician, Artist, and Writer Edited by Noel A. Carmack and Karen Lynn Davidson Volume 5 The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow Edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher Volume 6 A Widow’s Tale The 1884–1896 Diary of Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Transcribed and Edited by Charles M. -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

Southeastern Ohio's Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil

They Fought the War Together: Southeastern Ohio’s Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil War A Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gregory R. Jones December, 2013 Dissertation written by Gregory R. Jones B.A., Geneva College, 2005 M.A., Western Carolina University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Dr. Leonne M. Hudson, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Bradley Keefer, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Members Dr. John Jameson Dr. David Purcell Dr. Willie Harrell Accepted by Dr. Kenneth Bindas, Chair, Department of History Dr. Raymond A. Craig, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................iv Introduction..........................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: War Fever is On: The Fight to Define Patriotism............................................26 Chapter 2: “Wars and Rumors of War:” Southeastern Ohio’s Correspondence on Combat...............................................................................................................................60 Chapter 3: The “Thunderbolt” Strikes Southeastern Ohio: Hardships and Morgan’s Raid....................................................................................................................................95 Chapter 4: “Traitors at Home”: -

House and Home

House and Home The existential dimension in Anders T. Andersen’s production of John Gabriel Borkman Cécilia Elsen Master’s thesis in Ibsen Studies Center for Ibsen Studies, Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITETET I OSLO May 2015 II House and Home The existential dimension in Anders T. Andersen’s production of John Gabriel Borkman Cécilia Elsen Master’s thesis in Ibsen Studies Center for Ibsen Studies, Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITETET I OSLO May 2015 III © Cécilia Elsen 2015 The existential dimension in Anders T. Andersen’s John Gabriel Borkman http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The topic of the thesis is the relation between the concepts ‘house’ and ‘home’ in Ibsen’s drama. I believe that the relationship between house and home is common to his oeuvre in general and not specific to some plays. I study the relation between the concepts ‘house’ and ‘home’ in John Gabriel Borkman based on a performance I saw in Teater Ibsen in Skien in September 2012. In the first chapter, I support my claim that Ibsen's works have an existential dimension on the house/home concepts by drawing on Anthony Vidler (1992), Mark Sandberg (2001, 2007 and 2015) as well as Mark Wigley (1993). In the second chapter I explain by Heidegger why Anders T. Andersen was provoked by Ostermeier’s version of John Gabriel Borkman. Andersen found that Ostermeier had no sub- text – or in other words – no existential dimension. Although originally a Freudian concept I apply Heidegger's concept of the uncanny (das Unheimliche) in a metaphysical perspective drawing on Anette Storli Andersen’s master thesis based on Robert Wilson’s Peer Gynt. -

Hank Mobley No Room for Squares Mp3, Flac, Wma

Hank Mobley No Room For Squares mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: No Room For Squares Country: Japan Released: 2015 Style: Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1501 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1985 mb WMA version RAR size: 1349 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 825 Other Formats: MMF DXD AIFF WMA AUD FLAC MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Three Way Split 1 7:47 Written-By – Hank Mobley Carolyn 2 5:28 Written-By – Lee Morgan Up A Step 3 8:29 Written-By – Hank Mobley No Room For Squares 4 6:55 Written-By – Hank Mobley Me 'N You 5 7:15 Written-By – Lee Morgan Old World, New Imports 6 6:05 Written-By – Hank Mobley Carolyn (alt. take) 7 Written By – Lee Morgan No Room For Squares 8 Written By – Hank Mobley Syrup & Biscuits 9 Written By – Hank Mobley Comin' Back 10 Written By – Hank Mobley Credits Bass – Butch Warren, John Ore Design [Cover] – Reid Miles Drums – Philly Joe Jones* Liner Notes – Joe Goldberg Photography By [Cover Photo] – Francis Wolff Piano – Andrew Hill, Herbie Hancock Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By], Remastered By – Rudy Van Gelder Tenor Saxophone – Hank Mobley Trumpet – Donald Byrd, Lee Morgan Notes 2015 Japanese SHM-CD with 4 bonus tracks. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4988005850980 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Hank No Room For Squares BLP 4149 Blue Note BLP 4149 US 1964 Mobley (LP, Album, Mono) Hank No Room For Squares BST 84149 Blue Note BST 84149 US 1966 Mobley (LP, Album, RE) Blue Note, BST-84149, Hank No Room For Squares BST-84149, Heavenly France -

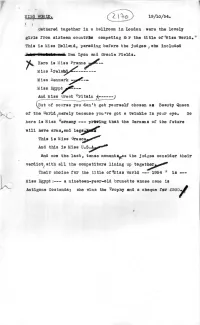

1,11 SS WQRID. F I ) to ) 19/10/54. I / Gathered Together in a Ballroom In

1,11 SS WQRID. f I ) to ) 19/10/54. I / Gathered together In a ballroom in London were the lovely girls from sixteen countrts competing £> r the title of "Miss World, This is Miss Holland, parading before the judges , who Included Ben Lyon and Grade Fields. Here is Miss Franc Mlss ^relahdyi^" Miss Denmark^^df-- Miss Kgyp^^"^ And Miss Great Britain j *\But of course you don't get yourself chosen aa Beauty Queen of the v/orld ^merely because you've got a twinkle In your eye. So here Is Miss uermany prlaing that the Germans of the future will have arms,and legSj This Is Miss Greece^ And this is Miss U.S.i^ And now the last, tense moments as the judges consider their verdict, with all the competitors lining up together. Their choice for the title of tilss World 1954 " is -— Miss Egypt a nineteen-year-old brunette whose name is Antigone Costanda; she wins the 'i'rophy and a cheque for £500./ London; Crowing "Kiss florid" 19th vet. 54 /London: At the Lyceum Ballroom, the spotlight rests on international beauty - sixteen lovelies competing for the Hiss World" title. From Holland - Conny Harteveldjmimtammtmarnms •*•!,!' #i# the Judging panel - which i.ncludes Ben Lyon and Grade Fields. "Miss France" - petite, brunette and sweet sixteen puts the "eve" in evening dress r^O While Irish eyes fire smiling for Connie Bodgers. this world-wide contest, organised by me oca Dancing and the Sunday iWr / Dispatch ^brings fui» tajunc beauty from Denmark - Grete Hoffenblad. / ®67B* is represented by Antigone Costanda - a Greek subject. -

Uneasy Assembly: Unsettling Home in Early Twentieth-Century American Cultural Production

Uneasy Assembly: Unsettling Home in Early Twentieth-Century American Cultural Production Camilla Perri Ammirati Canton, NY B.A., Carleton College, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………….i Introduction: “Come Right In”: Situating Narratives of Domecility…………………………………………….1 Chapter One: Solid American Spaces: From Domestic Standardization to Dilemmatic Democracy…………………………………….30 Chapter Two: “Their Only Treason”: Domestic Space and National Belonging in Djuna Barnes’ Ryder………………………………………………..68 Chapter Three: “Honor Bilt”: Constructions of Home in Absalom, Absalom!..………………………………...147 Chapter Four: “Home Thoughts”: Domestic Disarray and Buffet Flat Belonging in Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem………………………………..…216 Chapter Five: Lock and Key Blues: Mobile Domecility in the Recorded Works of Bessie Smith………………………………………………………..242 Coda: Talking With the House Itself…………………………………………………………………..314 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………...321 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my wonderful committee. Deborah McDowell has been an incredible director and mentor, not only providing invaluable intellectual guidance throughout this process but offering true insight and kindness beyond the bounds of the project that kept me going at critical moments. Victoria Olwell has worked closely with me through countless rough pages, offering vital feedback and support and re-invigorating my thinking at every step. In my first term of the program, Eric Lott ignited my enthusiasm and set me on an intellectual path that keeps me always thinking about the next set of questions worth asking. Our conversations over the course of this project have been essential both in shaping my thinking and in encouraging me to take the chance of pursuing ideas I believe in. -

An Artilleryman's Diary, by Jenkin Lloyd Jones 1

An Artilleryman's Diary, by Jenkin Lloyd Jones 1 An Artilleryman's Diary, by Jenkin Lloyd Jones The Project Gutenberg EBook of An Artilleryman's Diary, by Jenkin Lloyd Jones This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: An Artilleryman's Diary Author: Jenkin Lloyd Jones Release Date: July 21, 2010 [EBook #33211] Language: English An Artilleryman's Diary, by Jenkin Lloyd Jones 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN ARTILLERYMAN'S DIARY *** Produced by David Edwards, Stephen H. Sentoff and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive) AN ARTILLERYMAN'S DIARY [Illustration: Jenkin Lloyd Jones] Wisconsin History Commission: Original Papers, No. 8 AN ARTILLERYMAN'S DIARY BY JENKIN LLOYD JONES Private Sixth Wisconsin Battery WISCONSIN HISTORY COMMISSION FEBRUARY, 1914 TWENTY-FIVE HUNDRED COPIES PRINTED Copyright, 1914 The Wisconsin History Commission (in behalf of the State of Wisconsin) Opinions or errors of fact on the part of the respective authors of the Commission's publications (whether Reprints or Original Narratives) have not been modified or corrected by the Commission. For all statements, of whatever character, the Author alone is responsible. DEMOCRAT PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTER An -

Argentina Stun All Blacks for First-Ever Win Over New Zealand

Stroll takes maiden pole in Turkey to upstage title-chasing Hamilton SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 2020 PAGE 14 Argentina stun All Blacks for first-ever win over New Zealand AFP SYDNEY A gutsy Argentina stunned the All Blacks 25-15 Saturday to pull off one of rugby’s biggest upsets, consigning an embar- rassed New Zealand to their firstback-to-back defeats in almost a decade. Fly-half Nicolas Sanchez scored all the Pumas’ points to hand them their maiden victory over the rugby pow- erhouse in the 30 Tests they have played. Mario Ledesma’s side were given virtually no chance ahead of the Tri Nations match in Sydney after the coronavi- rus hindered their prepara- tions to just two low-key prac- tice games. It’s surreal what happened, not just the result but playing, getting on the field after everything that has happened this year. Argentina coach Mario Ledesma. But in their first Test since the World Cup last year, they pulled off a miracle. “It’s surreal what hap- pened, not just the result but playing, getting on the field after everything that has hap- pened this year,” said Argen- tina coach Ledesma. “Some of the boys haven’t seen their families for four months but they have all been positive... they have been awesome. “I think we will remember Argentina’s players celebrate victory with their fans at the end of 2020 Tri-Nations rugby match against New Zealand at Bankwest Stadium in Sydney, Australia, on Saturday. (AFP) this for a long time, not only the game but because of the their country which has gone points on the board in the fifth ill-discipline handed them an- special situation,” he added. -

Dtp1may27.Qxd (Page 1)

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C Bottoms up! Amisha Patel in THE TIMES OF INDIA Lopez waxes America? All the Tuesday, May 27, 2003 eloquent... world’s a stage! Page 9 Page 10 TO D AY S LUCKY 833 T wo little fleas Juhi miss India 884 838 Kitty Mirza America s Indepen-84 Your Dambola Ticket available in Delhi Times on 25th May, 2003 OF INDIA Numbers already announced : 81, 74, 68, 61, 42, 63, 49, 78 NEERAJ PAUL 150 seats to ride: You can’t miss this bus! ARUN KUMAR DAS these buses is 18 m in length, es being operational, we will le- informs Srivastav. Among the taken on the company which Times News Network with two coaches being linked ave no stone unturned to make ‘stones’ which need to be turn- will finally supply these vehi- via a vestibular system. The our venture a successful one,’’ ed over is the modification of cles to us.’’ t’s a ‘roll-model’ which pro- doors of these vehicles are tw- speed-breakers on the routes Going by the black and wh- mises to be a role model for ice the width of those in norm- HIGH CAPACITY along which these buses will ite of the DTC’s blueprint, five Iall other forms of public tr- al DTC buses to ena- operate —after all, corridors will be earmarked ansport in this city.After all, it ble two passengers the gap between the for these buses. One of these can make light work of a hea- to board and descend base of these buses routes will connect ISBT to vy load. -

The Globalization of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond Lauren E

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Fall 12-14-2012 The Globalization of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond Lauren E. Riggs University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons, Medicine and Health Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Riggs, Lauren E., "The Globalization of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond" (2012). Master's Theses. 33. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Globalization of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond Author: Lauren Riggs1 University of San Francisco Master of Arts in International Studies (MAIS) November 30, 2012 1 [email protected] The Globalization of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS In INTERNATIONAL STUDIES by Lauren Riggs November 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Under the guidance and approval of the committee, and approval by all the members, this thesis has been accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree.