Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

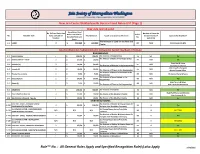

Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1)

Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington A non-profit tax-exempt religious organization, id # 54-1139623 New Jain Center/Shikharbandhi Derasar Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1) NEW JAIN CENTER LAND Amount per Fixed No. Of Fixed Nakro Line Number of Passes for Nakro Line Item for Rule** No Donation Item Items available for Total Donation Laabh to be given to the Donors the Ceremonies (if Sponsorship Available? Donation from each No. Donation applicable) Donor The Nirmaan of Land for the New Jain L-1 LAND 2$ 250,000 $ 500,000 R7 N/A Shah Kamlesh & Gita Center SHANKHESHWAR PARSHWANATH BHAGWAN (SHWETAMBAR) DERASAR RANGMANDAP S-1 RANGMANDAP 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Rangmandap R5 N/A Yes The Nirmaan of Dome in the Rangmandap S-2 RANGMANDAP - DOME 2$ 25,001 $ 50,002 R5 N/A Yes Shah Atul & Aruna S-3 Bhandar (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Bhandar in the Rangmandap Shah Dipak and Jyoti Shah Arvind & Sanyukta S-4 Trigado (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Trigado in the Rangmandap Ajmera Devang & Rani The Nirmaan of Musical Instruments in the S-5 Musical Instruments 1$ 5,001 $ 5,001 R5 N/A Dharamsi Manoj & Kanta Rangmandap The Nirmaan of Sound System in the S-6 Sound System 1$ 20,001 $ 20,001 R5 N/A Yes Rangmandap Shah Paresh & Shilpa S-7 Ghant (2) 2$ 5,001 $ 10,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Ghant in the Rangmandap Shah Harshid & Hemangini S-8 GHABHARA 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Ghabhara R5 N/A Yes Dalal Fakirchand and Manjula S-9 Main Ghabhara Door (s) 2$ 15,001 $ 30,002 The Nirman of the Ghabhara Door(s) R5 N/A -

Julia A. B. Hegewald

Table of Contents 3 JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD JAINA PAINTING AND MANUSCRIPT CULTURE: IN MEMORY OF PAOLO PIANAROSA BERLIN EBVERLAG Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 3 13.04.2015 13:45:43 2 Table of Contents STUDIES IN ASIAN ART AND CULTURE | SAAC VOLUME 3 SERIES EDITOR JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 2 13.04.2015 13:45:42 4 Table of Contents Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data is available on the internet at [http://dnb.ddb.de]. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Coverdesign: Ulf Hegewald. Wall painting from the Jaina Maṭha in Shravanabelgola, Karnataka (Photo: Julia A. B. Hegewald). Overall layout: Rainer Kuhl Copyright ©: EB-Verlag Dr. Brandt Berlin 2015 ISBN: 978-3-86893-174-7 Internet: www.ebverlag.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed and Hubert & Co., Göttingen bound by: Printed in Germany Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 4 13.04.2015 13:45:43 Table of Contents 7 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction: Jaina Manuscript Culture and the Pianarosa Library in Bonn Julia A. B. Hegewald ............................................................................ 13 Chapter 2 Studying Jainism: Life and Library of Paolo Pianarosa, Turin Tiziana Ripepi ....................................................................................... 33 Chapter 3 The Multiple Meanings of Manuscripts in Jaina Art and Sacred Space Julia A. -

Ancient Hindu Rock Monuments

ISSN: 2455-2631 © November 2020 IJSDR | Volume 5, Issue 11 ANCIENT HINDU ROCK MONUMENTS, CONFIGURATION AND ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES OF AHILYA DEVI FORT OF HOLKAR DYNASTY, MAHISMATI REGION, MAHESHWAR, NARMADA VALLEY, CENTRAL INDIA Dr. H.D. DIWAN*, APARAJITA SHARMA**, Dr. S.S. BHADAURIA***, Dr. PRAVEEN KADWE***, Dr. D. SANYAL****, Dr. JYOTSANA SHARMA***** *Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur C.G. India. **Gurukul Mahila Mahavidyalaya Raipur, Pt. R.S.U. Raipur C.G. ***Govt. NPG College of Science, Raipur C.G. ****Architectural Dept., NIT, Raipur C.G. *****Gov. J. Yoganandam Chhattisgarh College, Raipur C.G. Abstract: Holkar Dynasty was established by Malhar Rao on 29th July 1732. Holkar belonging to Maratha clan of Dhangar origin. The Maheshwar lies in the North bank of Narmada river valley and well known Ancient town of Mahismati region. It had been capital of Maratha State. The fort was built by Great Maratha Queen Rajmata Ahilya Devi Holkar and her named in 1767 AD. Rani Ahliya Devi was a prolific builder and patron of Hindu Temple, monuments, Palaces in Maheshwar and Indore and throughout the Indian territory pilgrimages. Ahliya Devi Holkar ruled on the Indore State of Malwa Region, and changed the capital to Maheshwar in Narmada river bank. The study indicates that the Narmada river flows from East to west in a straight course through / lineament zone. The Fort had been constructed on the right bank (North Wards) of River. Geologically, the region is occupied by Basaltic Deccan lava flow rocks of multiple layers, belonging to Cretaceous in age. The river Narmada flows between Northwards Vindhyan hillocks and southwards Satpura hills. -

Bhagwan Mahaveer & Diwali

Bhagwan Mahaveer & Diwali All the Jains celebrate the festival of Diwali with joy. Diwali is celebrated on the new-moon day of Kartik. On the night of that day, Bhagwan Mahavira attained Nirvan or deliverance and a state of absolute bliss. The Lord discarded the body and the bondage of all Karmas on that night, at Pawapuri In Uttara-puraana written by Acharya GunBhadra (7th or 8th century) it is mentioned that in the month of Kartika, krashna paksha, svati nakshatra and on the night of the 14th (dawn of the amavasya), lord Mahavira became a Siddha (attained nirvana). Bhagwan Mahavira, the 24th Jain Tirthankaras, attained Nirvana on this day at Pavapuri on Chaturdashi of Kartika: - | || Diwali festival was first time mentioned in Harivansha Purana written by Acharya Jinasena, and composed in the Shaka Samvat era in the year 705. Acharya Jinasena mentions that Bhagavan Mahavira, attained nirvana at Pavapuri in the month of Kartika, Krashna paksh, during swati nakshatra, at the time of dawn. In Harivamsha-Purana sloka 19 and in sloka 20 he writes that the gods illuminated Pavanagari by lamps to mark the occasion. Since that time the people of Bharat celebrate the famous festival of "Dipalika" to worship the Jinendra on the occasion of his nirvana. , | , || ( ) Tatastuh lokah prativarsham-aadarat Prasiddha-deepalikaya-aatra bharate, Samudyatah poojayitum jineshvaram Jinendra-nirvana vibhuti-bhaktibhak. It means, the gods illuminated Pavanagari by lamps to mark the occasion. Since that time, the people of Bharat celebrate the famous festival of "Dipalika" to worship the Lord Mahavira on the occasion of his nirvana. -

21 Aug 2019 174051563XWO

CONTENT LIST S. NO. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 2.0 INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT/ BACKGROUND INFORMATION 3-5 (i) IDENTIFICATION OF PROJECT & PROJECT PROPONENT 3 (ii) BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF NATURE OF THE PROJECT 4 (iii) NEED FOR THE PROJECT & ITS IMPORTANCE TO THE COUNTRY /REGION 4 (iv) DEMAND -SUPPLY 5 (v) DEMAND - SUPPLY GAP 5 (vi) EXPORT POSSIBILITY 5 (vii) DOMESTIC/EXPORT MARKETS 5 (viii) EMPLOYMENT GENERATION (DIRECT AND INDIRECT) DUE TO THE PROJECT 5 3.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 6-15 TYPE OF PROJECT INCLUDING INTERLINKED AND INDEPENDENT PROJECTS, 6 (i) IF ANY LOCATION (MAP SHOWING GENERAL LOCATION, SPECIFIC LOCATION, AND 7 (ii) PROJECT BOUNDARY & PROJECT SITE LAYOUT) WITH COORDINATES (iii) DETAILS OF ALTERNATIVE SITE CONSIDERED 9 (iv) SIZE OR MAGNITUDE OF OPERATION 9 (v) PROJECT DESCRIPTION WITH PROCESS DETAILS 9 RAW MATERIAL REQUIRED ALONG WITH ESTIMATED QUANTITY, LIKELY 14 (vi) SOURCE, MARKETING AREA OF FINAL PRODUCTS, MODE OF TRANSPORT OF RAW MATERIAL AND FINISHED PRODUCT RESOURCES OPTIMIZATION/ RECYCLING AND REUSE ENVISAGED IN THE 14 (vii) PROJECT, IF ANY, SHOULD BE BRIEFLY OUTLINED AVAILABILITY OF WATER ITS SOURCE, ENERGY /POWER REQUIREMENT AND 14 (viii) SOURCE QUANTITY OF WASTE TO BE GENERATED (LIQUID AND SOLID) AND SCHEME 15 (ix) FOR THEIR MANAGEMENT/DISPOSAL 4.0 SITE ANALYSIS 15 -19 (i) CONNECTIVITY 15 (ii) LAND FORM, LAND USE AND LAND OWNERSHIP 16 (iii) TOPOGRAPHY & DRAINAGE 16 EXISTING LAND USE PATTERN {AGRICULTURE, NON -AGRICULTURE, FOREST, 16 WATER BODIES (INCLUDING AREA UNDER CRZ)}, SHORTEST DISTANCES (iv) FROM THE PERIPHERY OF THE PROJECT TO PERIPHERY OF THE FORESTS, NATIONAL PARK, WILD LIFE SANCTUARY, ECO SENSITIVE AREAS, WATER i S. -

Diwali-Essay-In-English-And-Hindi

1 Diwali-Essay-In-English-And-Hindi Since Deepavali is a festival for more than 2 days, we have 2 or 3 new dresses. It gives a message of love, brotherhood and friendship. India is a land of Festivals. Diwali is celebrated to mark the day when Lord Ram came to Ayodhya. On this day Kali Puja performed in Bengal. For most of us Diwali is just a synonym to a night full of crackers, noise and smoke. The last day of Diwali is called as Bhaubij. Some days before Diwali we burn statues of evil King Ravana. People greet their relatives and friends with sweets and crackers. Diwali is one of them. The night of amavasya is transformed into Purnima by glory of diyas. It is a Hindu Festival. I usually have to be a vegetarian, because I go to the Alter and offer different sweets and fruits. There is a lot of noise and air pollution. Siddharth Bidwalkar. It is a festival for shopping. tatastuh lokah prativarsham-aadarat prasiddha-deepalikaya-aatra bharate samudyatah poojayitum jineshvaram jinendra-nirvana vibhuti-bhaktibhak. People of Ayodhya welcomed them with lighted oil lamps. At 6 pm we illuminate the house with candles and diyas. At dusk we do puja of Goddess Lakshmi. Do we have to pay such a heavy cost to buy a smile for ourselves. Diwali is the festival of Goddess Laxmi. Lots of people also start new ventures on this day after performing Lakshmi Puja. This is because Lord Rama defeated him. We cook sweets like kanawla, gateau patate, tekwa, gulap jamoun and many other delicacies. -

Volume : 57 Issue No. : 57 Month : April, 2005

Volume : 57 Issue No. : 57 Month : April, 2005 ACHARYASHREE MAHAPRAJNA'S MESSAGE TO GENERAL MUSHARRAF DELIVERED BY LOKESH MUNI 'LOKESH' AT NEW DELHI ACHARVA MAHAPRAGYA NOMINATED FOR COMMUNAL HARMONY AWARD "Pakistan and India have similar problems and worries. We only can fight poverty, illiteracy and diseases rampant in our region, if our region is peaceful. Your efforts towards strengthening world peace and creating a non-violent society are commendable. I hold the belief that the ensuing atmosphere of peace will help us diverting the enormous defense expenditures to resolve the above-mentioned problems. To deal with contending issues the idea of Anekanta or non-absolutism, which talks of relative viewpoints, as given by Bhagwan Mahavira, can help. Meeting and dialogue are the first steps in this direction." April, New Delhi. The prestigious "Communal Harmony Award" will be given to Acharya Mahapragya, the founder of "Ahimsa Yatra" for His valuable contribution in the field of National Unity and Communal Harmony. According to the Foundation of National Communal Harmony, Govt. of India, this prestigious award for the year 2004 will be given to His Holiness Acharya Mahapragya at a grand function in the National Capital. This award is given for the unique contribution to the unity and communal harmony in the country. The Award Committee, presided by Shri Bhairon Singh Shekshawat, the Hon'ble Vice-President of India, has choosen Acharya Mahapragya for this award for His remarkable work among several nominees. In this award Rs. 2 lakh and a memorandum are presented. The spokesperson of Ahimsa Yatra Muni Lokprakash Lokesh has expressed his joy and said that this award would certainly be the award to the great values of Indian Culture. -

Volume : 135 Issue No. : 135 Month : October, 2011

Volume : 135 Issue No. : 135 Month : October, 2011 *¤*.¸¸.·´¨`»* * Happy Diwali * *«´¨`·.¸¸.*¤* "May the festival of lights be the harbinger of joy and prosperity. As the holy occasion of Diwali is here and the atmosphere is filled with the spirit of mirth and love, here's hoping this festival of beauty brings your way, bright sparkles of contentment, that stay with you through the days ahead. Best wishes on Diwali and New year". DIWALI IN JAIN MYTHOLOGY Diwali is an important Hindu festival although it is observed by the Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists as well. Referred to as the “festival of lights,” Diwali marks the triumph of good over evil, and the lighting up of lamps is a custom that stands for celebration and optimism for mankind. Lights and lamps, specifically conventional diyas are an important aspect of Diwali celebrations. Fireworks are connected with the festival almost in every region of India. Diwali is of great significance in Jainism since on this day Lord Mahavira, the last of the jain Tirthankaras, achieved nirvana at Pavapuri. As per Jain custom, the principal follower of Mahavira, Ganadhar Gautam Swami, as well achieved absolute wisdom on this same day. Diwali is originally stated in Jain books as the date of the nirvana of Lord Mahavira. The earliest use of the word Diwalior Dipavali appears in Harivamsha Purana composed by Acharya Jinasena, written in Shaka Samvat 705. How is Jain Diwali Different from Hindu Diwali? The manner in which Jains commemorate Diwali differs in several ways from the one celebrated by the Hindus. There is an element of plainness in whatever the Jains do, and the festival of Diwali is different. -

GONE to the DOGS in ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée

GONE TO THE DOGS IN ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée Gone to the Dogs in ancient India Willem Bollée Published at CrossAsia-Repository, Heidelberg University Library 2020 Second, revised edition. This book is published under the license “Free access – all rights reserved”. The electronic Open Access version of this work is permanently available on CrossAsia- Repository: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ urn: urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-crossasiarep-42439 url: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/4243 doi: http://doi.org/10.11588/xarep.00004243 Text Willem Bollée 2020 Cover illustration: Jodhpur, Dog. Image available at https://pxfuel.com under Creative Commons Zero – CC0 1 Gone to the Dogs in ancient India . Chienne de vie ?* For Johanna and Natascha Wothke In memoriam Kitty and Volpo Homage to you, dogs (TS IV 5,4,r [= 17]) Ο , , ! " #$ s &, ' ( )Plato , * + , 3.50.1 CONTENTS 1. DOGS IN THE INDUS CIVILISATION 2. DOGS IN INDIA IN HISTORICAL TIMES 2.1 Designation 2.2 Kinds of dogs 2.3 Colour of fur 2.4 The parts of the body and their use 2.5 BODILY FUNCTIONS 2.5.1 Nutrition 2.5.2 Excreted substances 2.5.3 Diseases 2.6 Nature and behaviour ( śauvana ; P āli kukkur âkappa, kukkur āna ṃ gaman âkāra ) 2.7 Dogs and other animals 3. CYNANTHROPIC RELATIONS 3.1 General relation 3.1.1 Treatment of dogs by humans 3.1.2 Use of dogs 3.1.2.1 Utensils 3.1.3 Names of dogs 2 3.1.4 Dogs in human names 3.1.5 Dogs in names of other animals 3.1.6 Dogs in place names 3.1.7 Treatment of humans by dogs 3.2 Similes -

Evaluation of Infrastructure Facilities and Perception of Pilgrims at Palitana

International Journal of Applied Research 2021; 7(3): 284-289 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 8.4 Evaluation of infrastructure facilities and perception IJAR 2021; 7(3): 284-289 of pilgrims at Palitana www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 12-01-2021 Accepted: 14-02-2021 Tanmay Choksi and Anand Kapadia Tanmay Choksi M. Plan Student, Department Abstract of Architecture, Master of Background and Objective: Religious tourism seems to be one of the most preferred tourism after Urban and Regional Planning, business tourism in Gujarat. Palitana is one of the very important pilgrimage destination among six G.C Patel Institute of religious sites in Gujarat. The main objective of this study was to assess the existing infrastructure and Architecture, interior designing institutional framework for tourism in Palitana town and identify the gaps as well as to study perception and Fine Arts, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, of pilgrims at Palitana. Surat, Gujarat, India Methodology: Data collection was done in two phases. Primary data collection was done by using 16 item questionnaire was used to evaluate tourist perception. 100 tourists were evaluated by convenience Anand Kapadia sampling. Secondary data collection was done from the existing review of literature and various Associate Professor, government sources to find out the existing infrastructure facilities. Road network, transport facility, Department of Architecture, water supply, Sewerage and solid waste management, accommodation facilities, recreational facilities Master of Urban and Regional and tourist inflow were included in secondary data collection. Planning, G.C Patel institute Results and data analysis: 79% of tourists’ purpose was purely religious and they all were Jains. -

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab New Bond Street, London | 23 October, 2018 Registration and Bidding Form (Attendee / Absentee / Online / Telephone Bidding) Please circle your bidding method above. Paddle number (for office use only) This sale will be conducted in accordance with 23 October 2018 Bonhams’ Conditions of Sale and bidding and buying Sale title: Sale date: at the Sale will be regulated by these Conditions. You should read the Conditions in conjunction with Sale no. Sale venue: New Bond Street the Sale Information relating to this Sale which sets out the charges payable by you on the purchases If you are not attending the sale in person, please provide details of the Lots on which you wish to bid at least 24 hours you make and other terms relating to bidding and prior to the sale. Bids will be rounded down to the nearest increment. Please refer to the Notice to Bidders in the catalogue buying at the Sale. You should ask any questions you for further information relating to Bonhams executing telephone, online or absentee bids on your behalf. Bonhams will have about the Conditions before signing this form. endeavour to execute these bids on your behalf but will not be liable for any errors or failing to execute bids. These Conditions also contain certain undertakings by bidders and buyers and limit Bonhams’ liability to General Bid Increments: bidders and buyers. £10 - 200 .....................by 10s £10,000 - 20,000 .........by 1,000s £200 - 500 ...................by 20 / 50 / 80s £20,000