Opposition to Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss Or to Transfer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Taking Down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, Not Collaboration, Please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017

Taking down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, not collaboration, please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017 In the US there are already effective Trump boycotts seeking to delegitimise his political agenda. Internationally, protesters will be out wherever he goes. And from Africa, there are sound arguments to play a catalytic role, mainly because the most serious threat to humanity and environment is Trump’s climate change denialism. Consider two contrasting strategies to deal with the latest mutation of US imperialism: we should protest Donald Trump and Trumpism at every opportunity as a way to contribute to the unity of the world’s oppressed people, and now more urgently link our intersectional struggles; or we should somehow take advantage of his presidency to promote the interests of the ‘left’ or the ‘Global South’ where there is overlap in weakening Washington’s grip (such as in questioning exploitative world trading regimes). The latter position is now rare indeed, although before the election Hillary Clinton’s commitment to militaristic neoliberalism generated so much opposition that to some, the anticipated ‘paleo-conservatism’ of an isolationist-minded Trump appeared attractive. One international analyst of great reknown, Boris Kagarlitsky, makes this same argument this week largely because Trump is questioning pro-corporate ‘free trade’ deals. But the argument for selective cooperation with Trump was best articulated in Pambazuka as part of a series of otherwise compelling reflections by the Ugandan writer and former South Centre director Yash Tandon. Tandon might re-examine the ‘space’ he can ‘seize’ with Trump, the ‘fraud’ Since more than any other individual Tandon helped make the 1999 Seattle and Cancun World Trade Organisation summits a profound disaster for world elites, I take him very seriously. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Trumpism on College Campuses

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Trumpism on College Campuses Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1d51s5hk Journal QUALITATIVE SOCIOLOGY, 43(2) ISSN 0162-0436 Authors Kidder, Jeffrey L Binder, Amy J Publication Date 2020-06-01 DOI 10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Qualitative Sociology (2020) 43:145–163 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Trumpism on College Campuses Jeffrey L. Kidder1 & Amy J. Binder 2 Published online: 1 February 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract In this paper, we report data from interviews with members of conservative political clubs at four flagship public universities. First, we categorize these students into three analytically distinct orientations regarding Donald Trump and his presidency (or what we call Trumpism). There are principled rejecters, true believers, and satisficed partisans. We argue that Trumpism is a disunifying symbol in our respondents’ self- narratives. Specifically, right-leaning collegians use Trumpism to draw distinctions over the appropriate meaning of conservatism. Second, we show how political clubs sort and shape orientations to Trumpism. As such, our work reveals how student-led groups can play a significant role in making different political discourses available on campuses and shaping the types of activism pursued by club members—both of which have potentially serious implications for the content and character of American democracy moving forward. Keywords Americanpolitics.Conservatism.Culture.Highereducation.Identity.Organizations Introduction Donald Trump, first as a candidate and now as the president, has been an exceptionally divisive force in American politics, even among conservatives who typically vote Republican. -

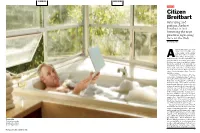

Citizen Breitbart Polarizing and Profane, Andrew Breitbart Is Fast Becoming the Most Powerful Right-Wing Force on the Web by STEVE ONEY

´+$>&!7¨ ´+$>&!7¨ PROFILE Citizen Breitbart Polarizing and profane, Andrew Breitbart is fast becoming the most powerful right-wing force on the Web BY STEVE ONEY ndrew breitbart sits in an Aeron chair at an iMac com- puter gazing out the sliding glass door of his Los Angeles home office. On the patio, a hulaA hoop and a portable basketball rim await his children’s return from school. Breitbart, 41, dressed on this late-winter day in his standard work uniform of a dirty oxford-cloth shirt and grungy khaki shorts, looks more like a surf bum than one of the most divisive figures in Amer- ica’s political and culture wars. Then his BlackBerry rings. The woman at the other end of the line, conservative fulminator Ann Coulter, is among Breitbart’s staunchest allies, and they soon are engaged in a spirited at- tack on liberals. “Their entire structure is writhing in diseased agony on the side of the road, and they don’t even realize it,” Breitbart says. But the left isn’t the only object of disdain. “I’m sick of this effete GOP nothing sandwich,” he adds, grow- ing more animated. “As long as everyone is so pristine and socially registered, we’re going to lose.” Shortly before signing off, Breitbart says, “The second I realized I liked being hated more than I liked being liked—that’s when the game began.” It’s a game he plays extraordinarily well. Breitbart has become the Web’s most com- bative conservative impresario—part new- media mogul, part Barnumesque scamp. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

What Drives Hyper-Partisan News Sharing: Exploring the Role of Source, Style, and Content

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Department Faculty Publication Series Communication 2020 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content Weiai Wayne Xu Yoonmo Sang Christopher Kim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_faculty_pubs 1 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content Weiai Wayne Xu Assistant Professor N334 Integrative Learning Center, Department of Communication University of Massachusetts – Amherst Amherst, MA 01003-1100 Phone: +001-(414)688-3059 Email: [email protected] Yoonmo Sang Assistant Professor Faculty of Arts & Design University of Canberra Email: [email protected] Christopher Kim Ph.D. Candidate Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra Email: [email protected] 2 A growing number of hyper-partisan alternative media outlets have sprung up online to challenge mainstream journalism. However, research on news sharing in this particular media environment is lacking. Based on the virality of sixteen partisan outlets’ coverage of immigration and using the latest computational linguistic algorithm, the present study probes how hyper- partisan news sharing is related to source transparency, content styles, and moral framing. The study finds that the most shared articles reveal author names, but not necessarily other types of author information. The study uncovers a salient link between moral frames and virality. In particular, audiences are more sensitive to moral frames that emphasize authority/respect, fairness/reciprocity, and harm/care. Keywords: news sharing, news diffusion, partisan media, Facebook, social media, moral framing, moral foundations theory 3 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content The 2016 U.S. -

Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right

Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Political Science | Volume 71 Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US With kind support of Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2019 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Typeset by Alexander Masch, Bielefeld Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-4670-2 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-4670-6 https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706 Contents Introduction | 7 Stephen Albrecht, Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston ANALYZING Understanding the Alt-Right. -

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................... 1 What Techniques Do Media Manipulators Use? ....... 33 Understanding Media Manipulation ............................ 2 Participatory Culture ........................................... 33 Who is Manipulating the Media? ................................. 4 Networks ............................................................. 34 Internet Trolls ......................................................... 4 Memes ................................................................. 35 Gamergaters .......................................................... 7 Bots ...................................................................... 36 Hate Groups and Ideologues ............................... 9 Strategic Amplification and Framing ................. 38 The Alt-Right ................................................... 9 Why is the Media Vulnerable? .................................... 40 The Manosphere .......................................... 13 Lack of Trust in Media ......................................... 40 Conspiracy Theorists ........................................... 17 Decline of Local News ........................................ 41 Influencers............................................................ 20 The Attention Economy ...................................... 42 Hyper-Partisan News Outlets ............................. 21 What are the Outcomes? .......................................... -

What Is a Community Land Trust?

Land in Common community land trust What is a Community Land Trust? The first Community Land Trust (CLT) was born from the visionary wor! of civil rights organi(ers /hirley /herrod, Charles /herrod, Bob /wann, /later King and others. They founded 1ew Communities, 2nc. in 3eorgia in 4+5+ as a collective farm to empower 'frican 'meri an families and ena t land 6usti e in the /outh. 7rawing on the ideas of politi al e onomist 8enry 3eorge, the 0ibbut( ooperative movement, and the 2ndian 3ramdan (“land gift”) movement, the CLT structure is rooted in balanced values of collective liberation and redistribution, community ownership of land, and individual freedom and responsibility 9a mi: well-suited for %ainers see!ing social change. CLTs are built on the idea of separating the ownership of land from the ownership of buildings and other “improvements.” The land is owned by the member-run, nonprofit trust as part of a shared commons, removing it permanently from the mar!et. This land is then leased to residents via an inheritable, renewable, +9-year, “ground lease.” ,uildings on the land are owned dire tly by the residents themselves and may be sold only at values that assure fair ompensation #not high profits) for owners and long-term a-ordability for future residents. Long-term prote tion of the land for agri ulture, conservation, a-ordable housing, and other ommunity-based purposes is a hieved; while se urity, autonomy, and participation in !ey land-related de isions by land residents is also ensured. Land in Common is governed by two groups of people" those who live on or use the land #$esident %embers& and those from the wider community ('ssociate Members) who support the vision, mission, and values of the organi(ation. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced individual views toward women one of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965.