Building on Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 20 Backup Bulletin Format on Going

gkfnL] nfsjftf] { tyf ;:s+ lt[ ;dfh Nepali Folklore Society Nepali Folklore Society Vol.1 December 2005 The NFS Newsletter In the first week of July 2005, the research Exploring the Gandharva group surveyed the necessary reference materials related to the Gandharvas and got the background Folklore and Folklife: At a information about this community. Besides, the project office conducted an orientation programme for the field Glance researchers before their departure to the field area. In Introduction the orientation, they were provided with the necessary technical skills for handling the equipments (like digital Under the Folklore and Folklife Study Project, we camera, video camera and the sound recording device). have completed the first 7 months of the first year. During They were also given the necessary guidelines regarding this period, intensive research works have been conducted the data collection methods and procedures. on two folk groups of Nepal: Gandharvas and Gopalis. In this connection, a brief report is presented here regarding the Field Work progress we have made as well as the achievements gained The field researchers worked for data collection in from the project in the attempt of exploring the folklore and and around Batulechaur village from the 2nd week of July folklife of the Gandharva community. The progress in the to the 1st week of October 2005 (3 months altogether). study of Gopalis will be disseminated in the next issue of The research team comprises 4 members: Prof. C.M. Newsletter. Bandhu (Team Coordinator, linguist), Mr. Kusumakar The topics that follow will highlight the progress and Neupane (folklorist), Ms. -

Rakam Land Tenure in Nepal

13 SACRAMENT AS A CULTURAL TRAIT IN RAJVAMSHI COMMUNITY OF NEPAL Prof. Dr. Som Prasad Khatiwada Post Graduate Campus, Biratnagar [email protected] Abstract Rajvamshi is a local ethnic cultural group of eastern low land Nepal. Their traditional villages are scattered mainly in Morang and Jhapa districts. However, they reside in different provinces of West Bengal India also. They are said Rajvamshis as the children of royal family. Their ancestors used to rule in this region centering Kuchvihar of West Bengal in medieval period. They follow Hinduism. Therefore, their sacraments are related with Hindu social organization. They perform different kinds of sacraments. However, they practice more in three cycle of the life. They are naming, marriage and death ceremony. Naming sacrament is done at the sixth day of a child birth. In the same way marriage is another sacrament, which is done after the age of 14. Child marriage, widow marriage and remarriage are also accepted in the society. They perform death ceremony after the death of a person. This ceremony is also performed in the basis of Hindu system. Bengali Brahmin becomes the priests to perform death sacraments. Shradha and Tarpana is also done in the name of dead person in this community. Keywords: Maharaja, Thana, Chhati, Panju and Panbhat. Introduction Rajvamshi is a cultural group of people which reside in Jhapa and Morang districts of eastern Nepal. They were called Koch or Koche before being introduced by the name Rajvamshi. According to CBS data 2011, their total number is 115242 including 56411 males and 58831 females. However, the number of Rajvamshi Language speaking people is 122214, which is more than the total number this group. -

Some Notes on Nepali Castes and Sub-Castes—Jat and Thar

SOME NOTES ON NEPALI CASTES AND SUB-CASTES- JAT AND THAR. - Suresh Singh This paper attempts to make a re-presentation of evolution and construction of Jat and Thar system among the Parbatya or hill people of Nepal. It seeks to expose the reality behind the myth that the large number of Aryans migrated from Indian plains due to Muslim invasion and conquered to become the rulers in Nepal, and the Mongoloids were the indigenous people. It also seeks to show the construction and reconstruction of identity of the different castes (Jats) and subcastes (Thars). The Nepalese history is lost in legends and fables. Archaeological data, which might shed light on the early years, are practically nonexistent or largely unexplored, because the Nepalese Government has not encouraged such research within its borders. However, there seem to be a number of sites that might yield valuable find, once proper excavation take place. Another problem seems to be that history writing is closely connected with the traditional conception of Nepali historiography, constructed and intervened by the efforts of the ruling elite. Many of the written documents have been re-presented to legitimatize the ruling elite’s claim to power. As it is well known from political history, the social history, too, becomes an interpretation from the view of the Kathmandu valley, and from the Indian or alleged Indian immigrants and priestly class. It is difficult to imagine, that Aryans came to Nepal in greater numbers about 600 years ago, and because of their mental superiority and their noble character, they were asked by the people to become the rulers of their small states. -

Lumbini Buddhist University

Lumbini Buddhist University Course of Study M.A. in Theravada Buddhism Lumbini Buddhist University Office of the Dean Senepa, Kathmandu Nepal History of Buddhism M.A. Theravada Buddhism First Year Paper I-A Full Mark: 50 MATB 501 Teaching Hours: 75 Unit I : Introductory Background 15 1. Sources of History of Buddhism 2 Introduction of Janapada and Mahajanapadas of 5th century BC 3. Buddhism as religion and philosophy Unit II : Origin and Development of Buddhism 15 1. Life of Buddha from birth to Mahaparinirvan 2. Buddhist Councils 3. Introduction to Eighteen Nikayas 4. Rise of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism Unit III: Expansion of Buddhism in Asia 15 1. Expansion of Buddhism in South: a. Sri Lanka b. Myanmar c. Thailand d. Laos, e. Cambodia 2. Expansion of Buddhism in North a. China, b. Japan, c. Korea, d. Mongolia e. Tibet, Unit IV: Buddhist Learning Centres 15 1. Vihars as seat of Education Learning Centres (Early Vihar establishments) 2. Development of Learning Centres: 1 a. Taxila Nalanda, b. Vikramashila, c. Odantapuri, d. Jagadalla, e. Vallabi, etc. 3. Fall of Ancient Buddhist Learning Centre Unit IV: Revival of Buddhism in India in modern times 15 1 Social-Religious Movement during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. 2. Movement of the Untouchables in the twentieth century. 3. Revival of Buddhism in India with special reference to Angarika Dhaminapala, B.R. Ambedkar. Suggested Readings 1. Conze, Edward, A Short History of Buddhism, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1980. 2. Dhammika, Ven. S., The Edicts of King Ashoka, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1994. 3. Dharmananda, K. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALA VAN RESEARCH NUMBERZ 1991 CONTENTS EDITORlAL._.................................................... _................................................................................... .3 REVIEW ARllCll 'Manyrs for democncy'; a ~yiew of rece nt Kathmandu publications: Manin Gaensz.le and Richard BurShan. ............................................................................................................. 5 AROIIVES The Cambridge EII:pcrimcntal Videodisc Project: Alan MlCfarlane ............................................. IS The NepaJ German Manuscript: PrescrYlOOn Project: Franz·KarI Ehrbanl. .................................. 20 TOPICAL REPORTS The study of oral tradition in Nepal: Comeille Jest ...................................................................... 25 Wild c:!:! a~e~ {7'~: :M~~~~~':~~~~~.~~.i~.. ~.~~~ . ~~.~.~................... 28 lI<IERVIEW with Prof. IsvlI BanJ. the new Viee·OIancellor of the Royal Nepal Academy, followed by lisl of CUlTellt Academy projects: Manin Gaens:z.ie .................................................................. 31 RESEARCH REPORTS Group projects; Gulmi and Argha·Khanci Interdisciplinary Progr.unme: Philippc Ramiret. ........................ 35 Nepal-Italian Joint Projecl on High.Altitide Research in the Himalayas ............................ 36 Oevdopmc:nt Stnltcgics fOf the Remote Mas of Nep&l ..................................................... 31 Indiyidual projects: Anna Schmid ............ , ..... , ................................................................ -

In Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police

Calling for Security and Justice in Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police Author Karon Cochran-Budhathoki Editors Shobhakar Budhathoki Nigel Quinney Colette Rausch With Contributions from Dr. Devendra Bahadur Chettry Professor Kapil Shrestha Sushil Pyakurel IGP Ramesh Chand Thakuri DIG Surendra Bahadur Shah DIG Bigyan Raj Sharma DIG Sushil Bar Singh Thapa Printed at SHABDAGHAR OFFSET PRESS Kathmandu, Nepal United States Institute of Peace National Mall at Constitution Avenue 23rd Street NW, Washington, DC www.usip.org Strengthening Security and Rule of Law Project in Nepal 29 Narayan Gopal Marg, Battisputali Kathmandu, Nepal tel/fax: 977 1 4110126 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] © 2011 United States Institute of Peace All rights reserved. © 2011 All photographs in this report are by Shobhakar Budhathoki All rights reserved. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Richard H. Solomon, President of the United States Institute of Peace VII Acknowledgments IX List of Abbreviations XI Chapter 1 Summary 1.1 Purpose and Scope of the Survey 3 1.2 Survey Results 4 1.2.1 A Public Worried by Multiple Challenges to the Rule of Law, but Willing to Help Tackle Those Challenges 4 1.2.2 The Vital Role of the NP in Creating a Sense of Personal Safety 4 1.2.3 A Mixed Assessment of Access to Security 5 1.2.4 Flaws in the NP’s Investigative Capacity Encourage “Alternative -

Click View Final R2R Resolution

International Conference on Experience of Earthquake Risk Management, Preparedness and Reconstruction in Nepal June 18-20, 2018, Kathmandu, Nepal RESOLUTION (Kathmandu Declaration – 2018) Background Nepal hosted RISK2RESILIENCE (R2R): An International Conference on Experience of Earthquake Risk Management, Preparedness and Reconstruction in Nepal during June 18-20, 2018 in Kathmandu, Nepal. The Government of Nepal, Ministry of Home Affairs, Nepal (MoHA), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), and National Society for Earthquake Technology-Nepal (NSET) in association with various agencies and partners jointly organized the Conference. The Conference was held with the main Objectives to: ↗ Critically look back at what we all collectively did for Earthquake Risk Reduction & Preparedness in Nepal in the past decades in the Light of 2015 Gorkha Earthquake sequence ↗ Critically examine the experience of Earthquake Reconstruction so far, and also ↗ Looking forward to helping set the Way Forward in the Long Journey of Disaster Risk Management in Nepal The Conference brought together 240 participants including national and international citizens. A total of 40 international professionals from 13 different countries participated. Throughout the proceeding of the Conference, there were 15 Keynote Speeches made on key issues; and total 220 more persons including government officials, DRR Experts, Practitioners and Academia shared their ideas and views as speakers, presenters or panelists. Total 12 -

Nepali Times on Facebook Printed at Jagadamba Press | 01-5250017-19 | Follow @Nepalitimes on Twitter 8 - 14 JUNE 2012 #608 OP-ED 3

#608 8 - 14 June 2012 16 pages Rs 30 Hot spot here are two types of carbon that cause Himalayan snows to Tmelt. One is carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning that heats up the atmosphere through the greenhouse- effect. The other is tiny particles of solid carbon given off by smokestacks and diesel exhausts that are deposited on snow and ice and cause them to melt faster. Both contribute to the accelerated meltdown of the Himalaya. Yak herders below Ama Dablam (right) now cross grassy meadows where there used to be a glacier 40 years ago. Nepal’s delegation at the Rio+20 Summit in Brazil later this month will be arguing that the country cannot sacrifi ce economic growth to save the environment. Increasingly, that is looking like an excuse to not address pollution in our own backyard. Full story by Bhrikuti Rai page 12-13 NO WATER? NO POWER? NO PROBLEM How to live without electricity and water page 5 Mother country Federalism and governance were not the only contentious issues in the draft constitution that was not passed on 27 May. Provisions on citizenship were even more regressive than in the interim constitution. There is now time to set it right. EDITORIAL page 2 OP-ED by George Varughese and Pema Abrahams page 3 BIKRAM RAI 2 EDITORIAL 8 - 14 JUNE 2012 #608 MOTHER COUNTRY Only the Taliban treats women worse hen the Constituent Assembly expired two 27 May. Our “progressive” politicians were too busy weeks ago, there was disappointment but haggling over state structure and forms of governance to Walso relief at having put off a decision on notice. -

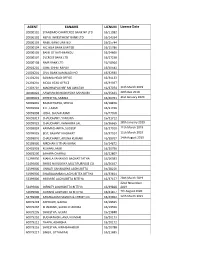

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

International Conference on Invasive Alien Species Management

Proceedings of the International Conference on Invasive Alien Species Management NNationalational TTrustrust fforor NatureNature ConservationConservation BBiodiversityiodiversity CConservationonservation CentreCentre SSauraha,auraha, CChitwan,hitwan, NNepalepal MMarcharch 2525 – 227,7, 22014014 Supported by: Dr. Ganesh Raj Joshi, the Secretary of Ministry of Forests and Soil Conserva on, inaugura ng the conference Dignitaries of the inaugural session on the dais Proceedings of the International Conference on Invasive Alien Species Management National Trust for Nature Conservation Biodiversity Conservation Centre Sauraha, Chitwan, Nepal March 25 – 27, 2014 Supported by: © NTNC 2014 All rights reserved Any reproduc on in full or in part must men on the tle and credit NTNC and the author Published by : NaƟ onal Trust for Nature ConservaƟ on (NTNC) Address : Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal PO Box 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel : +977-1-5526571, 5526573 Fax : +977-1-5526570 E-mail : [email protected] URL : www.ntnc.org.np Edited by: Mr. Ganga Jang Thapa Dr. Naresh Subedi Dr. Manish Raj Pandey Mr. Nawa Raj Chapagain Mr. Shyam Kumar Thapa Mr. Arun Rana PublicaƟ on services: Mr. Numraj Khanal Photo credits: Dr. Naresh Subedi Mr. Shyam Kumar Thapa Mr. Numraj Khanal CitaƟ on: Thapa, G. J., Subedi, N., Pandey, M. R., Thapa, S. K., Chapagain, N. R. and Rana A. (eds.) (2014), Proceedings of the InternaƟ onal Conference on Invasive Alien Species Management. Na onal Trust for Nature Conserva on, Nepal. This publica on is also available at www.ntnc.org.np/iciasm/publica ons ISBN: 978-9937-8522-1-0 Disclaimer: This proceeding is made possible by the generous support of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the American people through the United States Agency for InternaƟ onal Development (USAID) and the NaƟ onal Trust for Nature ConservaƟ on (NTNC). -

Nepali Times

#650 5 - 11 April 2013 20 pages Rs 50 NOW WITH “We must push for June.” BIKRAM RAI In a free-wheeling interview UCPN (Maoist) Chairman Pushpa Kamal Truth and Reconciliation Media: “The media is a bit Dahal spoke to Nepali Times and Himal Khabarpatrika on Thursday Bill: “It meets international confused and some like your about the need for the government and Election Commission to still standards. We Nepalis listen newspaper are a bit prejudiced aim to have elections in June. He defended his commitment to address a bit too much to outsiders. against me and our party.” human rights violations committed during the war through the Truth We have to get out of the habit of seeking international and Reconciliation Commssion and urged Nepalis not to always seek approval for everything we nepalitimes.com foreign approval for domestic issues. He did not rule out eventual do.” unity with the Baidya faction. Full interview in Nepali on Himal Khabarpatrika on Sunday. English Madhes: “I want to contest translation, podcast, and video clips online Elections: “We must push accountable to the people and elections from the Madhes and for elections in June, it is allowed to govern for full five address the grievances of the still possible. If the High years. At present, coalition Tarai and bring all Madhesis Level Political Committee leaders always need money and into the national mainstream. which I chair can convince muscle to stay in power and We can’t treat Madhesis as if the smaller parties, then the have no time to think about they are Indians.” government and the EC can stability and growth.” MURAL solve the technical issues. -

India–Nepal Relations Overview

India–Nepal Relations Overview 1. As close neighbours, India and Nepal share a unique relationship of friendship and cooperation characterized by open borders and deep-rooted people-to-people contacts of kinship and culture. There has been a long tradition of free movement of people across the borders. Nepal has an area of 147,181 sq. kms. and a population of 29 million. It shares a border of over 1850 kms in the east, south and west with five Indian States – Sikkim, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand – and in the north with the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. The India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950 forms the bedrock of the special relations that exist between India and Nepal. Under the provisions of this Treaty, the Nepalese citizens have enjoyed unparalleled advantages in India, availing facilities and opportunities at par with Indian citizens. Nearly 6 million Nepali citizens live and work in India. 2. There are regular exchanges of high level visits and interactions between India and Nepal. Nepalese Prime Minister Shri Sushil Koirala visited India to attend the swearing-in ceremony of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi on 26 May 2014. In 2014, Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi visited Nepal twice – in August for a bilateral visit and in November for the SAARC Summit – during which several bilateral agreements were signed. India and Nepal have several bilateral institutional dialogue mechanisms, including the India-Nepal Joint Commission co-chaired by External Affairs Minister of India and Foreign Minister of Nepal. 3.