A Father and Son Remember It All Differently

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin Ames Avid Editor

Gavin Ames Avid Editor Profile Gavin is an exceptionally talented editor. Fast, creative, and very technically minded. He is one of the best music editors around, with vast live multi-cam experience ranging from The Isle of Wight Festival, to Take That, Faithless and Primal Scream concerts. Since excelling in the music genre, Gavin went on to develop his skills in comedy, editing Shooting Stars. His talents have since gone from strength to strength and he now has a wide range of high-end credits under his belt, such as live stand up for Bill Bailey, Steven Merchant, Ed Byrne and Angelos Epithemiou. He has also edited sketch comedy, a number of studio shows and comedy docs. Gavin has a real passion for editing comedy and clients love working with him so much that they ask him back time and time again! Comedy / Entertainment / Factual “The World According to Jeff Goldblum” Series 2. Through the prism of Jeff Goldblum's always inquisitive and highly entertaining mind, nothing is as it seem. Each episode is centred around something we all love — like sneakers or ice cream — as Jeff pulls the thread on these deceptively familiar objects and unravels a wonderful world of astonishing connections, fascinating science and history, amazing people, and a whole lot of surprising big ideas and insights. Nutopia for National Geographic and Disney + “Guessable” In this comedy game show, two celebrity teams compete to identify the famous name or object inside a mystery box. Sara Pascoe hosts the show with John Kearns on hand as her assistant. Alan Davies and Darren Harriott are the team captains, in a format that puts a twist on classic family games. -

Best Online Travel Shows — Vancouver

TRAVEL EDITOR’S NOTE I’m optimistic once we are again allowed to travel we’re going to see a tourism boom not seen since the 1960s. Until then, be safe and avoid any unnecessary travel. For those looking to travel vicariously (or seeking to plan your next trip once we have a new normal), we asked freelancer Jay Gentile to update his list of the best travel shows to binge watch. I’d also like to thank those who have shared their travel stories and postcards — I’ll share them with our readers when I can. TRAVEL Dave Pottinger, [email protected] VANCOUVER SUN SATURDAY, APRIL 4, 2020 PAGE C10 Starring Vancouver travel journalist Robin Esrock, and Julia Dimon, Word Travels takes viewers into the world of travel writing in a show spanning 36 countries. WORD TRaVELS BEST ONLINE TRAVEL SHOWS 10 Now is the perfect opportunity to discover a new favourite program to feed your wanderlust while sidelined at home, writes Jay Gentile. ANTHONY BOURDAIN: do, and visits with local militia PARTS UNKNOWN groups to learn about the Second Long regarded as the travel Amendment. They also spend show against which all other time on Chicago’s South Side at travel shows are judged, Antho- a rap video shoot, explore why ny Bourdain changed the game Portland is the strip-club capital in food-focused television the of the United States, and throw minute his award-winning show their own street parade in New debuted on CNN in 2013. While Orleans. many have tried, no one has been able to uncover the soul of WORD TRAVELS: THE TRUTH a place and its people quite like BEHIND THE BYLINE the legendary former chef and Although it is listed on Amazon author. -

Page 1 of 125 © 2016 Factiva, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Colin's Monster

Colin's monster munch ............................................................................................................................................. 4 What to watch tonight;Television.............................................................................................................................. 5 What to watch tonight;Television.............................................................................................................................. 6 Kerry's wedding tackle.............................................................................................................................................. 7 Happy Birthday......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Joke of the year;Sun says;Leading Article ............................................................................................................... 9 Atomic quittin' ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Kerry shows how Katty she really is;Dear Sun;Letter ............................................................................................ 11 Host of stars turn down invites to tacky do............................................................................................................. 12 Satellite & digital;TV week;Television.................................................................................................................... -

Saints and Sinners: Lessons About Work from Daytime TV

Saints and sinners: lessons about work from daytime TV First draft article by Ursula Huws for International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics Introduction This article looks at the messages given by factual TV programmes to audiences about work, and, in particular, the models of working behaviour that have been presented to them during the period following the 2007‐8 financial crisis. It focuses particularly, but not exclusively, on daytime TV, which has an audience made up disproportionately of people who have low incomes and are poorly educated: an audience that, it can be argued, is not only more likely than average to be dependent on welfare benefits and vulnerable to their withdrawal but also more likely to be coerced into entering low‐paid insecure and casual employment. It argues that the messages cumulatively given by ‘factual’ TV, including reality TV programmes ostensibly produced for entertainment as well as documentaries, combine to produce a particular neoliberal model of the deserving worker (counterposed to the undeserving ‘scrounger’ or ‘slacker’) highly suited to the atomised and precarious labour markets of a globalised economy. This is, however, a model in which there are considerable tensions between different forms of desired behaviour: on the one hand, a requirement for intense, individualised and ruthless competitiveness and, on the other, a requirement for unquestioning and self‐sacrificing loyalty and commitment to the employer and the customer. These apparently contradictory values are, however, synthesised in a rejection, often amounting to demonisation, of collective values of fairness, entitlement and solidarity. The context Despite the explosive growth of the internet and multiplication of devices for accessing it, television remains the main means by which most people absorb narrative information. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films. -

Desirée Ivegbuna Offline Editor Avid

Desirée Ivegbuna Offline Editor Avid Profile Desiree is a brilliant up and coming editor with over 8 years of experience. Having worked in some of Soho’s largest facilities she is no stranger to fast paced, high pressure environments and always keeps her cool! Des has a particular passion for comedy, observational documentaries and character driven stories that she can really get to the heart of. She is conscientious and hard-working with the added bonus of being bubbly and very easy to work with! Credits “The Repair Shop” Series 8. 1 x 60min. A heart-warming antidote to throwaway culture, The Repair Shop shines a light on the wonderful treasures to be found in homes across the country. Enter a workshop filled with expert craftspeople, bringing loved pieces of family history and the memories they hold back to life. Ricochet for BBC Two “Weekend Escapes with Greg Wallace” 1 x 60min. Travelogue series which sees Wallace exploring various cities in search of the ideal weekend. In each city he’ll be experiencing the culture, exploring the history and, of course, indulging in the local cuisine. Rumpus Television for Channel 5 “Warship Life at Sea” 1 x 60min. Documentary series documenting everyday life onboard the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Duncan. Assembly editor Artlab for Channel 5 “SAS Who Dares Wins” Season 5. 1 x 47min. Twenty-five men and women, including an ex-SAS operator working undercover as a mole, face the latest intense course beginning with a swim to a remote Scottish island. Assembly editor Minnow Films for Channel 4 “Auschwitz Untold- In colour” 1 x 45min. -

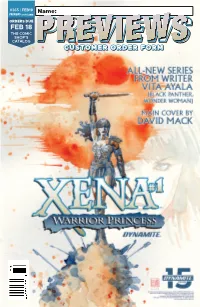

Feb 18 Customer Order Form

#365 | FEB19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE FEB 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 11:11:39 AM SAVE THE DATE! FREE COMICS FOR EVERYONE! Details @ www.freecomicbookday.com /freecomicbook @freecomicbook @freecomicbookday FCBD19_STD_comic size.indd 1 12/6/2018 12:40:26 PM ASCENDER #1 IMAGE COMICS LITTLE GIRLS OGN TP IMAGE COMICS AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF THE STORM #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SHE COULD FLY: THE LOST PILOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA ASCENDER #1 TURTLES #93 STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IMAGE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING IDW PUBLISHING TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES #93 IDW PUBLISHING THE WAR OF THE REALMS: JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT FAITHLESS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO THE WAR OF LITTLE GIRLS THE REALMS: OGN TP JOURNEY INTO IMAGE COMICS MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF XENA: THE STORM #1 WARRIOR DARK HORSE COMICS PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IDW PUBLISHING SHE COULD FLY: FAITHLESS #1 THE LOST PILOT #1 BOOM! STUDIOS DARK HORSE COMICS Feb19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 3:02:07 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strangers In Paradise XXV Omnibus SC/HC l ABSTRACT STUDIOS The Replacer GN l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Mary Shelley: Monster Hunter #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Bronze Age Boogie #1 l AHOY COMICS Laurel & Hardy #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Jughead the Hunger vs. -

CREATIVE SWINDON Cheats Death on Still a Magnet for Special Report on the Up-And-Coming Mount Kilimanjaro Logistics Businesses That Are Creating a Buzz

County Business Publishing £1.50 Volume 29 Number 8 July 2011 01793 615393 www.swindon-business.net [email protected] Loads of Lucky to be alive. opportunity. Swindon lawyer Why Swindon is CREATIVE SWINDON cheats death on still a magnet for Special report on the up-and-coming Mount Kilimanjaro logistics businesses that are creating a buzz Pages 12 & 13 PAGES 8 & 9 Back page News Brief Apprentice star visits town and says ‘You’re hired’ Swindon-born Nick Hewer, Lord Sugar's right-hand man on The Apprentice, returned to his roots to help celebrate Plan 500’s success. The plain-speaking PR man-turned reluctant TV star, pictured right , gave his backing to the scheme, which is creating 500 work-related opportunities for the town’s jobless youngsters, at an event at the STEAM museum. Representatives from around 140 companies attended the high-profile breakfast event - and many are now considering signing up to take part in the scheme Plan 500 has now surpassed the 400-opportunity mark and is on course to hit 500 soon, gaining recognition from the Government along the way as one of the best projects of its kind in the country. August Green Special Full story, p3 Swindon Business News goes a shade of green next month with a special edition devoted to all things environmentally-sustainable, low- Demolish old industrial carbon and waste-reducing. Features will focus on Green IT and how firms can use it to drive down costs, low- estates, council is told carbon buildings, alternative energy, waste and resource management, Pressure is growing on Swindon against the advice of the council’s environmentally-sensitive transport, Council to tear down some of the planning officers who had said the and the easiest ways to 'green up' your town’s outdated industrial estates and scheme could meet part of Swindon’s business - saving money and the redevelop the sites for housing while growing need for new employment planet. -

Dennis Potter: an Unconventional Dramatist

Dennis Potter: An Unconventional Dramatist Dennis Potter (1935–1994), graduate of New College, was one of the most innovative and influential television dramatists of the twentieth century, known for works such as single plays Son of Man (1969), Brimstone and Treacle (1976) and Blue Remembered Hills (1979), and serials Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986) and Blackeyes (1989). Often controversial, he pioneered non-naturalistic techniques of drama presentation and explored themes which were to recur throughout his work. I. Early Life and Background He was born Dennis Christopher George Potter in Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire on 17 May 1935, the son of a coal miner. He would later describe the area as quite isolated from everywhere else (‘even Wales’).1 As a child he was an unusually bright pupil at the village primary school (which actually features as a location in ‘Pennies From Heaven’) as well as a strict attender of the local chapel (‘Up the hill . usually on a Sunday, sometimes three times to Salem Chapel . .’).2 Even at a young age he was writing: I knew that the words were chariots in some way. I didn’t know where it was going … but it was so inevitable … I cannot think of the time really when I wasn’t [a writer].3 The language of the Bible, the images it created, resonated with him; he described how the local area ‘became’ places from the Bible: Cannop Ponds by the pit where Dad worked, I knew that was where Jesus walked on the water … the Valley of the Shadow of Death was that lane where the overhanging trees were.4 I always fall back into biblical language, but that’s … part of my heritage, which I in a sense am grateful for.5 He was also a ‘physically cowardly’6 and ‘cripplingly shy’7 child who felt different from the other children at school, a feeling heightened by his being academically more advanced. -

John Clifford Mortimer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2m3n990k No online items Finding Aid to the John Clifford Mortimer Papers Processed by Bancroft Library staff; revised and completed by Kristina Kite and Mary Morganti in October 2001; additions by Alison E. Bridger in February 2004, October 2004, January 2006 and August 2006. Funding for this collection was provided by numerous benefactors, including Constance Crowley Hart, the Marshall Steel, Sr. Foundation, Elsa Springer Meyer, the Heller Charitable and Educational Fund, The Joseph Z. and Hatherly B. Todd Fund, and the Friends of the Bancroft Library. The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the John Clifford BANC MSS 89/62 z 1 Mortimer Papers Finding Aid to the John Clifford Mortimer Papers Collection number: BANC MSS 89/62 z The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Bancroft Library staff; revised and completed by Kristina Kite and Mary Morganti; additions and revisions by Alison E. Bridger Date Completed: October 2001; additions and revisions February 2004, October 2004, January 2006, August 2006 Encoded by: James Lake © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: John Clifford Mortimer papers, Date (inclusive): circa 1969-2005 Collection Number: BANC MSS 89/62 z Creator: Mortimer, John Clifford, 1923- Extent: Number of containers: 46 boxes Linear feet: 18.4 Repository: The Bancroft Library. -

Birmingham Cover

Warwickshire Cover Online.qxp_Warwickshire Cover 23/09/2015 11:38 Page 1 THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE WARWICKSHIRE ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 358 OCTOBER 2015 MEERA SYAL TALKS ABOUT ANITA AND ME AT THE REP GRAND DESIGNS contemporary home show at the NEC INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS EVENTS FOOD & DRINK & MUCH MORE! HANDBAGGED Moira Buffini’s comedy visits the Midlands interview inside... REP (FP) OCT 2015.qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 10:32 Page 1 Contents October Region 1 .qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 21:49 Page 1 October 2015 Strictly Nasty Craig Revel Horwood dresses for Annie Read the interview on page 42 Jason Donovan Moira Buffini Grand Designs stars in Priscilla Queen Of The talks about Handbagged Kevin McCloud back at the NEC Desert page 27 interview page 11 page 69 INSIDE: 4. News 11. Music 24. Comedy 27. Theatre 44. Dance 51. Film 63. Visual Arts 67. Days Out 81. Food @whatsonbrum @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Birmingham What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Publishing + Online Editor: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 WhatsOn Editorial: Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 MAGAZINE GROUP Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Chris Eldon Lee, Heather Kincaid, Katherine Ewing, Helen Stallard Offices: Wynner House, Managing Director: Paul Oliver Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell Chris Atherton Bromsgrove St, Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 Birmingham B5 6RG This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine.