Bacteria in the Grand Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relation of Sediment Load and Flood-Plain Formation to Climatic Variability, Paria River Drainage Basin, Utah and Arizona

Relation of sediment load and flood-plain formation to climatic variability, Paria River drainage basin, Utah and Arizona JULIA B. GRAF U.S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division, 375 S. Euclid, Tucson, Arizona 85719 ROBERT H. WEBB U.S. Geological Survey, 1675 W. Anklam Road, Tucson, Arizona 85745 RICHARD HEREFORD U.S. Geological Survey, Geologic Division, 2255 North Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 ABSTRACT sediment load for a given discharge declined fill that rises 1-5 m above the modern channel abruptly in the early 1940s in the Colorado bed. Flood-plain deposits are present in all Suspended-sediment load, flow volume, River at Grand Canyon (Daines, 1949; Howard, major tributaries of the Paria River. The area of and flood characteristics of the Paria River 1960; Thomas and others, 1960; Hereford, flood plains is slightly greater than 20 km2, and were analyzed to determine their relation to 1987a). The decline in suspended-sediment sediment volume is estimated to be about 40 climate and flood-plain alluviation between loads has been attributed to improved land use million m3 (Hereford, 1987c). Typically, flood 1923 and 1986. Flood-plain alluviation began and conservation measures initiated in the 1930s plains are not present in first-order drainage ba- about 1940 at a time of decreasing magnitude (Hadley, 1977). A change in sediment-sampler sins but are present in basins of second and and frequency of floods in winter, summer, type and in methods of analysis have been higher order where the stream channel is uncon- and fall. No floods with stages high enough to discounted as causes for the observed decrease fined and crosses nonresistant bedrock forma- inundate the flood plain have occurred since (Daines, 1949; Thomas and others, 1960). -

Colorado River Managment Plan Annual Report Fiscal Year 2012

U.S. Department of Interior GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK National Park Service COLORADO RIVER MANAGEMENT PLAN ANNUAL REPORT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2012 Project Number 140653 Contributions by: Vanya Pryputniewicz, Outdoor Recreation Planner Jennifer Dierker, Archeologist Linda Jalbert, Wilderness Coordinator Lisa Kearsley, Biological Technician Brett G Dickson, Principal Investigator, NAU Valerie Horncastle, Senior Research Specialist, NAU Luke Zachman, Senior Research Specialist, NAU For More Information contact: Vanya Pryputniewicz 928-638-7659 [email protected] Colorado River Management Plan Annual Report for FY2012 Page 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Purpose and Need ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Mitigation Program ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Results and Observations ......................................................................................................................... -

Executive Summary U.S

Glen Canyon Dam Long-Term Experimental and Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement PUBLIC DRAFT Executive Summary U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region National Park Service, Intermountain Region December 2015 Cover photo credits: Title bar: Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon National Park Glen Canyon Dam: T.R. Reeve High-flow experimental release: T.R. Reeve Fisherman: T. Gunn Humpback chub: Arizona Game and Fish Department Rafters: Grand Canyon National Park Glen Canyon Dam Long-Term Experimental and Management Plan December 2015 Draft Environmental Impact Statement 1 CONTENTS 2 3 4 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. vii 5 6 ES.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 7 ES.2 Proposed Federal Action ........................................................................................ 2 8 ES.2.1 Purpose of and Need for Action .............................................................. 2 9 ES.2.2 Objectives and Resource Goals of the LTEMP ....................................... 3 10 ES.3 Scope of the DEIS .................................................................................................. 6 11 ES.3.1 Affected Region and Resources .............................................................. 6 12 ES.3.2 Impact Topics Selected for Detailed Analysis ........................................ 6 13 ES.4 -

Quantifying the Base Flow of the Colorado River: Its Importance in Sustaining Perennial Flow in Northern Arizona And

1 * This paper is under review for publication in Hydrogeology Journal as well as a chapter in my soon to be published 2 master’s thesis. 3 4 Quantifying the base flow of the Colorado River: its importance in sustaining perennial flow in northern Arizona and 5 southern Utah 6 7 Riley K. Swanson1* 8 Abraham E. Springer1 9 David K. Kreamer2 10 Benjamin W. Tobin3 11 Denielle M. Perry1 12 13 1. School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, US 14 email: [email protected] 15 2. Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, US 16 3. Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, US 17 *corresponding author 18 19 Abstract 20 Water in the Colorado River is known to be a highly over-allocated resource, yet decision makers fail to consider, in 21 their management efforts, one of the most important contributions to the existing water in the river, groundwater. This 22 failure may result from the contrasting results of base flow studies conducted on the amount of streamflow into the 23 Colorado River sourced from groundwater. Some studies rule out the significance of groundwater contribution, while 24 other studies show groundwater contributing the majority flow to the river. This study uses new and extant 1 25 instrumented data (not indirect methods) to quantify the base flow contribution to surface flow and highlight the 26 overlooked, substantial portion of groundwater. Ten remote sub-basins of the Colorado Plateau in southern Utah and 27 northern Arizona were examined in detail. -

The Colorado River a NATURAL MENACE BECOMES a NATIONAL RESOURCE ' '

The Colorado River A NATURAL MENACE BECOMES A NATIONAL RESOURCE ' ' I Comprehensive Report on the Development of ze Water Resources of the Colorado River Basin for rrigation, Power Production, and Other Beneficial Ises in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming By THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR J . A . Krug, Secretary SPONSORED BY AND PREPARED UNDER THE GENERAL SUPERVISION OF THE BUREAU OF RECLAMATION Michael W. Straus, Commissioner E. A. Morit-, Director, Region 3 ; E. O. Larson, Director, Region 4 MARCH 1 946 1P 'A m 4„ M 1i'leming Library Grand Canyon Colleg P . )x 11097 Contents Page PROPOSED REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF THE Explorations 46 INTERIOR Settlement 48 Page Population 49 Letter of June 6,1946, from the Acting Commissioner, Chapter III . DIVIDING THE WATER 53 3 Bureau of Reclamation Virgin Conditions 55 REGIONAL DIRECTORS' REPORT Early Development of the River 56 Summary of Conditions in the Early 1920's . 59 Map of Colorado River Basin Facing 9 Between the Upper and Lower Basins 59 Scope and Purpose 9 Between United States and Mexico . 66 Authority for the Report 9 DEVELOPING THE BASIN Cooperation and Acknowledgments 9 Chapter IV. 69 Description of Area 10 Upper Basin 72 Problems of the Basin 11 Labor Force 72 Water Supply 12 Land Ownership and Use 73 Division of Water 13 Soils 73 Future Development of Water Resources 13 Agriculture 73 Table I, Present and Potential Stream Depletions in Minerals and Mining 80 the Colorado River Basin 14 Lumbering 85 Potential Projects 14 Manufacturing 86 Table II, Potential Projects in the Colorado River Transportation and Markets . -

Clear-Water Tributaries of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, Arizona: Stream Ecology and the Potential Impacts of Managed Flow by René E

Clear-water tributaries of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, Arizona: stream ecology and the potential impacts of managed flow by René E. Henery ABSTRACT Heightened attention to the sediment budget for the Colorado River systerm in Grand Canyon Arizona, and the importance of the turbid tributaries for delivering sediment has resulted in the clear-water tributaries being overlooked by scientists and managers alike. Existing research suggests that clear-water tributaries are remnant ecosystems, offering unique biotic communities and natural flow patterns. These highly productive environments provide important spawning, rearing and foraging habitat for native fishes. Additionally, clear water tributaries provide both fish and birds with refuge from high flows and turbid conditions in the Colorado River. Current flow management in the Grand Canyon including beach building managed floods and daily flow oscillations targeting the trout population and invasive vegetation has created intense disturbance in the Colorado mainstem. This unprecedented level of disturbance in the mainstem has the potential to disrupt tributary ecology and increase pressures on native fishes. Among the most likely and potentially devastating of these pressures is the colonization of tributaries by predatory non-native species. Through focused conservation and management tributaries could play an important role in the protection of the Grand Canyon’s native fishes. INTRODUCTION More than 490 ephemeral and 40 perennial tributaries join the Colorado River in the 425 km stretch between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead. Of the perennial tributaries in the Grand Canyon, only a small number including the Paria River, the Little Colorado River and Kanab Creek drain large watersheds and deliver large quantities of sediment to the Colorado River mainstem (Oberlin et al. -

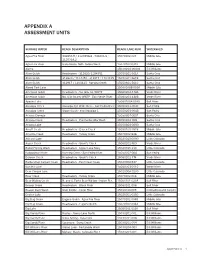

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

FISH of the COLORADO RIVER Colorado River and Tributaries Between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead

FISH OF THE COLORADO RIVER Colorado River and tributaries between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead ON-LINE TRAINING: DRAFT Outline: • Colorado River • Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (GCDAMP) • Native Fishes • Common Non-Native Fishes • Rare Non-Native Fishes • Standardized Sampling Protocol Colorado River: • The Colorado River through Grand Canyon historically hosted one of the most distinct fish assemblages in North America (lowest diversity, highest endemism) • Aquatic habitat was variable ▫ Large spring floods ▫ Cold winter temperatures ▫ Warm summer temperatures ▫ Heavy silt load • Today ▫ Stable flow releases ▫ Cooler temperatures ▫ Predation Overview: • The Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program was established in 1997 to address downstream ecosystem impacts from operation of Glen Canyon Dam and to provide research and monitoring of downstream resources. Area of Interest: from Glen Canyon Dam to Lake Mead Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (Fish) Goals: • Maintain or attain viable populations of existing native fish, eliminate risk of extinction from humpback chub and razorback sucker, and prevent adverse modification to their critical habitat. • Maintain a naturally reproducing population of rainbow trout above the Paria River, to the extent practicable and consistent with the maintenance of viable populations of native fish. Course Purpose: • The purpose of this training course “Fish of the Colorado River” is to provide a general overview of fish located within the Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam downstream to Lake Mead and linked directly to the GCDAMP. • Also included are brief explanations of management concerns related to the native fish species, as well as species locations. Native Fishes: Colorado River and tributaries between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead Bluehead Sucker • Scientific name: Catostomus discobolus • Status: Species of Special Concern (conservation status may be at risk) • Description: Streamlined with small scales. -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River- Salton Sea Area By BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72 610761 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract . _.._.-_. ._...._ ..._ _-...._ ...._. ._.._... El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction .._____. ..... .._..__-. - ._...-._..__..._ _.-_ ._... 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek .._________________.____.___-._____. _ E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam ____________ 2 Havasu Creek __._____________-...- _ __ -26 Lees Ferry .._._..__.___.______.__________ 4 Virgin River ..__ .-.._..-_ --....-. ._. 26 Grand Canyon ................._____________________..............._... 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam ..........._._..- -_-._-._................-._._._._... 8 Hoover Dam .__-.....-_ .... .-_ . _. 26 Lake Havasu - -_......_....-..-........ .........._............._.... 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead ............-... .-.....-..... 26 Imperial Dam .--. ........_. ...___.-_.___ _.__.__.._-_._.___ _ 12 Bill Williams River ......._.._......__.._....._ _......_._- 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 . -

Grand Canyon National Park

To Bryce Canyon National Park, KANAB To St. George, Utah To Hurricane, Cedar City, Cedar Breaks National Monument, To Page, Arizona To Kanab, Utah and St. George, Utah V and Zion National Park Gulch E 89 in r ucksk ive R B 3700 ft R M Lake Powell UTAH 1128 m HILDALE UTAH I L ARIZONA S F COLORADO I ARIZONA F O gin I CITY GLEN CANYON ir L N V C NATIONAL 89 E 4750 ft N C 1448 m RECREATION AREA A L Glen Canyon C FREDONIA I I KAIBAB INDIAN P Dam R F a R F ri U S a PAGE RESERVATION H 15 R i ve ALT r 89 S 98 N PIPE SPRING 3116 ft I NATIONAL Grand Canyon National Park 950 m 389 boundary extends to the A MONUMENT mouth of the Paria River Lees Ferry T N PARIA PLATEAU To Las Vegas, Nevada U O Navajo Bridge M MARBLE CANYON r e N v I UINKARET i S G R F R I PLATEAU F I 89 V E R o V M L I L d I C a O r S o N l F o 7921ft C F 2415 m K I ANTELOPE R L CH JACOB LAKE GUL A C VALLEY ALT P N 89 Camping is summer only E L O K A Y N A S N N A O C I O 89T T H A C HOUSE ROCK N E L E N B N VALLEY YO O R AN C A KAIBAB NATIONAL Y P M U N P M U A 89 J L O C FOREST O K K D O a S U N Grand Canyon National Park- n F T Navajo Nation Reservation boundary F a A I b C 67 follows the east rim of the canyon L A R N C C Y r O G e N e N E YO k AN N C A Road to North Rim and all TH C OU Poverty Knoll I services closed in winter. -

Boatman's Quarterly Review

the journal of the Grand Canyon River Guides, Inc. • voulme 25 number 2 • summer 2012 boatman’s quarterly review boatman’s Prez Blurb•Farewell •BooksKen,2Arts&RonGTSLand • GTSRiver HMcD Signature•Chub Relocation•OverflightsBackoftheBoat Food ForThought •Conflict/Harmony •SpringFlowers Art Gallenson boatman’s quarterly review Prez Blurb …is published more or less quarterly by and for GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES. Á’ÁT’ÉÉH, HAPPY RIVER SEASON! It’s already that GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES time of year again! Many of you have already is a nonprofit organization dedicated to Yhad a couple or more commercial trips under your belt on the Colorado, Grand Canyon or other Protecting Grand Canyon rivers. As a fellow river guide, I know that the begin- Setting the highest standards for the river profession ning of the river season or before your first trip begs Celebrating the unique spirit of the river community the main questions of “Where did I put that?” or “What Providing the best possible river experience am I forgetting?” At least for me, it’s the stressful part of the beginning of river season but I often remind General Meetings are held each Spring and Fall. Our myself that I’m going to a place of solitude, beauty, Board of Directors Meetings are generally held the first friendship, and adventure. It is also a stark reminder wednesday of each month. All innocent bystanders are that this place we all call home and our “office” is urged to attend. Call for details. always under observation from the constant threats of STAFF exploitation from development, mining and increased Executive Director LYNN HAMILTON visitation.